|

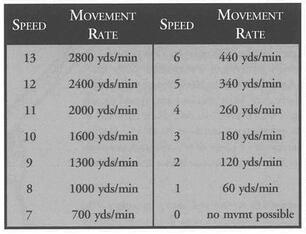

One of the distinctions that divides fans of different editions of D&D is the question, 'How long is a melee round?' Some lexical detective work is needed to figure out what D&D originally intended. Back in 1974, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson explain (in the Underworld & Wilderness Adventures expansion) that a 'turn' is ten minutes and there are 10 1-minute melee rounds in a turn. Gygax retained the 1-minute melee round for 1st and 2nd edition AD&D, justifying it like this: The 1 minute melee round assumes much activity – rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on. Once during this period each combatant has the opportunity to get a real blow in (1st ed. AD&D Players Hand Book, p39) The 1-minute round seems to have its roots in the wargaming superstructure that D&D emerged from. One minute allows a squad or battalion to move, line up, fire, generally 'take their turn'. Combat in wargaming is typically all-or-nothing, so in that 1-minute of action you might completely eliminate your opponent. Adapting this to tabletop RPGs produces a high level of abstraction. You're free to imagine a lot of cinematic business going on surrounding your solitary 'to hit' roll or spell. But it leads to absurdities. An armoured warrior can only manage short bursts of energetic combat, but combat in D&D can easily last 10+ melee rounds, especially in a 'cleric fight' (a fight between well-armoured characters with low damage output). That's 10+ minutes of huffing and puffing in quilted doublets, thick leather jerkins, mail hauberks... Impossible. While Gygax was working in minutes, Eric Holmes was tasked with presenting Basic D&D (1977) and unilaterally decided that the time frame for combat should be in seconds rather than minutes: Each turn is ten minutes except during combat where there are ten melee rounds per turn, each round lasting ten seconds (Basic D&D Blue Book, p9) Now that ten round fight lasts just under two minutes: much more realistic. Subsequent editions of Basic D&D - the 1981 beautiful edition by Tom Moldvay and the 1983 ugly edition by Frank Mentzer - retain this 10-second melee round. Moreover, Basic D&D charted the path that other RPGs followed. For example, Runequest defines fantasy roleplaying for non-D&D folk and hit upon a 12-second melee round. The melee round is 12 seconds long. One complete round of attacks, parries, spells, and movement happens during ascenario. (Runequest 2nd ed, p14) 12 seconds is long enough for it to eat your shield Then, in the 21st century, 3rd edition D&D switches to the 6-second melee round, which has been the standard ever since. Take that, Gygax. Holmes is vindicated! A round represents about 6 seconds in the game world. During a round, each participant takes a turn (5th ed. D&D Players Hand Book, p189) There are arguments to make both for the combat round as minute or handful of seconds. The 1-minute-round moves combat towards 'theatre of the mind' with a lot of improvised 'business' going on around the decisive blows. Tasks like picking up weapons, unsheathing swords, notching arrows, drinking potions and finding spell components are easy to fit into this stream of activity and don't penalise the character. But if you find such protracted combat unlikely, the 6/10-second-round offers a more moment-by-moment approach that suits tactical combat better, where facing and flanking matters; where you forfeit your action if you're caught unawares, if you have to ready your weapon; where it matters where you are standing and who you can see and whether you can reach somebody in time to hit them. But is it really likely that an armoured warrior can hit someone 6-10 times in a minute - or even twice that if they are high-level? Can archers really fire 12-20 arrows a minute, minute after minute? Can you really cast 6-10 spells in a minute, with combat going on all around you? The fast melee round seems to credit PCs with incredible vigour. Real Life Comparisons A medieval longbowman at the Battle of Crecy (1346) was expected to fire 12 shots a minute. That involves drawing and firing a longbow, which most people would find pretty punishing to do just the once. On the other hand, it didn't involve much aiming: longbows work because they drop a swarm of yard-long steel skewers onto the enemy, willy-nilly. And of course, this could not be sustained for more than a few minutes. A shortbow might be fired 20-30 times a minute, but, again, no one could sustain this. All of which favours the 10-second melee round more than the 6-second one, which allows a bow to be fired up to a dozen times. Moreover, how many arrows actually get fired in a 1-minute round? If the round assumes lots of 'shots' which only pin the opponent down or harry them, but include a couple of 'true' or 'effective' shots that have "the opportunity to get a real blow in", it's reasonable to assume an archer fires at least half a dozen arrows per minute, probably twice that. An archer with a quiver of 20 arrows will have fired all of the after a couple of 1-minute melee rounds. Jogging speeds in minutes and seconds Usain Bolt's world record is to run 100m in 9.58 seconds. That's about 200ft in 6 seconds or 330ft in 10 seconds. The average jogger covers 70ft in 6 seconds or 120ft in 10 seconds or a whopping 730ft in a minute. Now if we halve that 'jogging speed' for someone running in heavy clothing, carrying adventuring gear, in a darkly lit tunnel, over uneven and slippery floor, you probably get 35ft in a 6-second melee round or 60ft in a 10-second round and let's say 360ft in a minute. But it's even worse in heavy armour, carrying a sword, trying not to get killed. Even if we assume adventurers are trained to run around in armour, 35/60/360ft per round has to be the maximum and a more likely distance is 20ft in 6 seconds or 30ft in 10 seconds and 180ft in a minute, which is walking speed. 1st Edition AD&D (PHB p102) allows unarmoured characters to travel 120ft in a 1-minute round, which suggests a very cautious sort of walk. Halve that for characters in metal armour, which is a weary shuffle. D&D 5th edition has an unencumbered human traveling 60ft in a 6-second round, which is rather speedy, more like an actual jog along a smooth pavement. Basic D&D (Molvay or Mentzer) has unencumbered characters jogging 40ft in a 10-second round and lumbering 20ft in metal armour, which is comparable to AD&D speeds. Holmes Basic D&D allows 20ft movement in a melee round, 10ft if armoured, which is almost immobile by comparison. One of the less-remarked aspects of the development of D&D through the editions is how much faster everyone is now. A combat minute in Forge Out Of Chaos Indie RPG Forge confesses its derivation from D&D (especially 1st edition AD&D) in myriad ways, but its adoption of the 1-minute melee round is one of the clearest. After all, who would come up with such a profoundly un-intuitive gaming convention on their own? But Forge imports some ideas from other RPGs that sit uneasily with the abstract 'melee minute'. For example: armour. D&D treats armour as an impediment to hitting which works fine in a melee minute, where it's assumed your opponent takes lots of swipes against you and armour merely shifts the odds of being hurt in your favour. In 1978, Runequest took another direction, with armour deducting from dealt damage, which works well with its more simulationist 12-second round, in which combatants deal each other single bone-crunching blows. Forge tries to have it both ways. Armour makes you harder to hit (in an abstract, when-you-average-it-all-up sort of way) but also absorbs the damage dealt (in a specific that-blow-didn't-get-through sort of way). However, Forge usually inhabits the theatre-of-the-mind world of AD&D combat, where miniatures and battle maps are optional because positioning and facing barely matter. In Forge, you're either attacking an enemy's DV1 (including shield and Awareness bonus) or DV2 (no shield, no Awareness bonus) and there's nothing more specific than that. At least AD&D perversely factored in whether you were making a flank attack on someones shield-side or not (forgetting, temporarily, the rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on of a melee-minute). But then Forge also forgets its melee-minute time frame when it obsesses about the range of magic spells and invites you to 'pump' spells to increase the range. Who cares what the range is when the spell is being cast in a busy minute in which you can dash over 100ft to get close to someone? Back in Holmes Basic, when a Magic-User might jog 20ft and an armoured Elf lumber 10ft, spell range mattered. Forge bases movement on the Speed (SPD) characteristic, determined for PCs using 1d4+1 (2-5). 'Yards' is an oddity: all the spell ranges are in feet. It's probably an unedited error and I'm always happy to enforce the convention that yards apply outside the dungeon but once you're underground, all yards count as feet. Forge also lacks any rules for encumbrance (but I offer house rules), so we have to assume these distances apply to unarmoured, unencumbered characters. If SPD 3 is the human norm, then adventurers are moving around much faster than in AD&D. If we apply AD&D logic, then characters in non-metal armour lurch about at 3/4 this speed and metal armour in 1/2 this speed. Nonetheless, if you've got SPD 5 then, even in plate mail, you will cover an impressive 170ft in a melee minute, much faster than AD&D. (I'm not even going to get into the whole conceptual muddle about whether SPD is supposed to represent reflexes or brute strength, the latter of which matters more for hauling yourself across a combat zone in armour.) If you can cover this sort of distance in a melee-minute, you don't worry too much about the range requirements of bows (which Forge also dispenses with) or spells. You just jog until you're close enough to your opponent and ZAP! Does anybody use melee-minutes any more? Gary Gygax ported the concept of the melee-minute into AD&D and Forge cloned it in an unreflective moment, but neither game really gets to grips with the implications. Gygax links his melee-minutes to another of D&D's defining concepts: Hit Points. What does it mean for a high level character to amass Hit Points sufficient to endure any number of sword blows? They haven't increased in literal physical toughness, but rather such areas as skill in combat and similar life-or-death situations, the "sixth sense" which warns the individual of some otherwise unforeseen events, sheer luck and the fantastic provisions of magical protections and/or divine protection (Dungeon Master's Guide, p82) In other words, some 'hits' in combat aren't even 'hits' at all. They're like the lost lives of a cat. The axe whistles through the space where your head was a moment ago, but some instinct made you duck. You lose Hit Points, representing pushing your luck, but you're physically unharmed. Yet, in another mood, Gygax is devoting pages in the Dungeon Master's Guide (e.g. pp52-3, 64, 69) to tactical movement, as if he were offering rules to a skirmish game with the action paced out in heartbeats, forgetting that all this is redundant in a rules set where, each minute, characters move great distances ("rushes, retreats") and the 'to hit' roll represents shaving away your opponent's luck rather than actually stabbing them. You can see why later editions of D&D followed Holmes down the heartbeat route of melee-moments rather than melee-minutes. Yet it leaves D&D with the preposterous institution of Hit Points, now bereft of its only justification, that a damaging 'hit' in combat doesn't necessarily involve any physical contact. If D&D can't square the circle of melee-time, then I can't 'fix' Forge's hybrid concoction either. In Forge, Hit Points are calculated from Stamina and don't balloon as you gain experience: a 'hit' in Forge is clearly something that leaves cuts and bruises. You use binding kits to regain your Hit Points, which you wouldn't do if all you'd lost was some good luck. In Forge, armour absorbs damage: if the armour deteriorates, then surely the axe did hit you! The long melee-minute loses its rationale. If I convert to the 'melee moment' approach - and I like the feel of Holmes' 10-second melee round - then all of Forge's spells last way too long and there's no point in 'pumping' them for extra duration (although extra range might become relevant again since unarmoured SPD 3 characters would only move 60ft per round or 30ft in plate mail). We can at least be consistent about the melee-minute approach. There doesn't seem to be anything to be done about the weirdness of two-handed swords which get swung once every two minutes. The convention comes from Holmes, with his snapshot 10-second rounds. Gygax did away with it in a moment of lucidity, but Forge ports it straight back in because it's really hard to make yourself remember that your melee rounds last an entire minute! Keeping track of arrows fired during a melee-minute seems irrational. In that space of time, an archer will fire almost all her arrows, then gather up the fallen ones to fire again. To represent depletion, just house rule that the archer's quiver goes down by 1d6 arrows every round, representing shafts that cannot be easily recovered. Then, at the end of the battle, the archer gathers them all back, minus a few lost or broken ones (perhaps, reducing the total stock by 1d6). In this sort of time frame, combatants can reach just about any area of the battlefield that their (rather large) movement allowance permits. Forge is onto something by treating tactical positioning as a simple DV1 (they saw you coming) vs DV2 (they didn't, or they're engaged in combat with somebody else). Place your miniature wherever you want to be on the battle map at the start of each melee minute. Or dispense with miniatures altogether! OSR dungeoncrawling without miniatures? I think I'd better think it out again...

0 Comments

I've spent time looking at the apocalyptic mythology set out in FORGE OUT OF CHAOS, as a basis for its system of Divine Magic, an explanation for its races and clerical classes and its (rather overlooked) implications for fantasy world-building. Time now to take a deep dive and explore the mythology on its own terms. Just what are its values and themes? After all, a myth, even a careless and derivative myth, is a tightly packaged bundle of meanings - it's an answer in story form to the fundamental questions of existence. So what answers do the myths of Enigwa's creation, the war between Berethenu & Grom and the Banishment provide? Tolkien & Kibbean Creation Myths

The Kibbe Brothers have clearly taken points from Tolkien. For example, in The Silmarillion (1977), Tolkien sets out the Ainulindalë (the Music of the Ainur) and Valaquenta (the Story of the Valar). A mysterious creator-God named Iluvatar brings the world into existence. Similarly, the Kibbes introduce Enigwa as the world-creator. World-creation is a task that Tolkien's Iluvatar shares with his created servitors, the Ainur or Angels. He delegates creative power to them, but one of them, Melkor, the greatest of angel-kind, pursues his own vision, disrupting Iluvatar's harmony, to which Iluvatar responds by deepening and complicating his symphony with richer themes to incorporate Melkor's rebellion into a satisfying whole. The Ainur are then given the opportunity to enter their creation and live within it as the Valar (Powers), i.e. embodied angels or earthbound gods. In the Kibbean creation-myth, Enigwa creates the world without collaboration: "he personally forged each mountain, planted each tree, chiselled each river." He then creates the gods and inserts them into his world so that they can "explore their father's creation.". Enigwa withdraws and the gods, left with autonomy, start to develop diverging agendas. "Although most were good at heart, some became chaotic, others aggressive, still others lustful and greedy." The gods fall into discord and Enigwa has to return and unite them in a shared project. There are apparent similarities here (creator-God, lesser divine offspring, rebellious autonomy, the Creator restores harmony). Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created a myth that is purposefully analogous to the Christian one. Iluvatar is the Judeo-Christian God who creates free willed agents. He then adapts his creation to their free-willed choices, responding to their deviance with deeper and richer harmony, drawing beauty from ugliness, redemption from rebellion, holiness from hardship. Melkor of course is Lucifer, the errant angel. Tolkien's creation myth demonstrates why the creation of free-will necessitates the creation of a world, and a world which contains difficult features, but a world in which transcendent goodness is possible. The Kibbean myth is not Judeo-Christian but Darwinian. The Creator-God brings into existence, not free-willed minds, but a material world. Free-will emerges from Enigwa's absence, as rational beings explore the world through trial-and-error. It's a Behaviourist myth of learning through experience, of positive and negative reinforcement, with the gods developing in different directions, like B.F. Skinner's rats in a gigantic cage. There's no suggestion that Enigwa intends his divine children to evolve into these diverse personalities or even that he foresaw it. Although the text describes Enigwa as a "kindly father" he functions rather more like a dispassionate scientist: God-as-detached-observer. Unlike Iluvatar, he doesn't incorporate free-will and rebellion into his overall creative vision, he merely suppresses it when present and allows it to flourish when he is absent. Noxious characteristics in the world (deserts, miasmic swamps, volcanic rifts, predatory animals, parasitic wasps, diseases) are part of Iluvatar's compromise with free-will, but are outright distoetions of Enigwa's purposes, put there by his errant children. Free-willed agents don't seem to be part of Enigwa's plan so much as a surprising side-effect of it. Evil emerges from the absence of God or the failure of his foresight. In Tolkien, God's foresight is absolute and even Melkor's rebellion becomes the means by which a deeper, nobler and more surprising moral order emerges: "And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined." This distinction, between Tolkien's divinely ordered but morally complicated creation and the Kibbes' disordered and lawless creation, leads to a different conception of Humanity. What a piece of work is man In Tolkien's myth, the created world awaits the birth of Iluvatar's physical creatures, the Elves. Most of the history of Middle-Earth is the history of the Elves: their journeyings, songs, romances and craftsmanship and - later - their noble but doomed war against Melkor/Morgoth. In Tolkien's Christian imagination, the Elves represent an Unfallen Humanity, Adam and Eve's children without original sin: immortal, virtuous, the peers of angels, the icons of God. Crucially, they're not boring. Immortality and goodness are compatible with having adventures, taking risks, experiencing peril, making mistakes. The Oath of Fëanor drives some Elves to to dreadful things, but apparently without malice. Humans appear later, a sort of divine afterthought. They are mortal, frail, unlovely and lack innate wisdom. They have one thing that Elves lack: the Gift of Death. An odd sort of gift, but one that relates them more fully to the Mystery of God than the Elves and even the Valar (who are bound to the world even if their bodies are slain). Humans are a paradox: the furthest from the divine in terms of innate power, the closest in ultimate destiny. And of course, mortality makes their brief lives into possible vehicles for self-transcendence. The courage and hope and faith of Humanity exceeds anything Elves can experience. This places Humanity in a clear Christian framework: humans are simultaneously central and peripheral, exalted and lowly, the highest and the lowest of creatures. It's an insight Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Hamlet:

In Christian thought, humanity has no innate value; humans are central to the drama of creation only insofar as they are loved by God, and loved insofar as they are sinners and suffer. In the Kibbean myth, Humanity is created by the gods as a shared project and entrusted to them by a departing Enigwa: "Help them learn of the world and its wonders. Instruct them as teachers and watch over them as shepherds." There seems to be folksy wisdom in what Enigwa does. To unite the querulous gods, he gives them a joint project and duty of care. One is put in mind of a parent giving squabbling children pet guinea pigs or hamsters and saying, 'You'll have to take turns feeding and cleaning them!' Regardless, Enigwa does not seem to know his children well. Once he departs, they fall to fighting again and this time their human pets are repurposed as warriors. Others gods come to Humanity's aid, but since they too employ humans as soldiers and raw materials for their ventures into species-creation, their advocacy is equivocal at best. Moreover, Enigwa leaves the gods with a parting instruction: a prohibition on teaching Magic to humans, "for Magic is the power of the divine alone and not meant for the ungodly." Of course, the gods violate this ban pretty quickly, promoting their human lieutenants to necromancers, elementalists and beast mages. This stands Tolkien's conception on its head. Humanity is now a central project on Juravia: the ur-species from which all other fantasy races are derived. However, there's nothing of the divine about them and no transcendent mystery to their destiny. They are a biological instrument, intended to unite the gods but retooled as weaponry. Humanity finds itself at the tail-end of a long story, present in the world to serve purposes not of its own choosing and shaped by contingencies set in motions aeons earlier. This is a truly Darwinian perspective. Insofar as there is a Fallen race in Kibbean mythology, it's the gods themselves, who renege on their duty of care and violate the prohibition on teaching Magic. Tolkien's rather nuanced Christian sensibilities appear here in a very debased form. There are people (not usually Christians themselves) who imagine the Genesis myth to be the story of an irresponsible Creator placing his human wards in an experimental environment with only cryptic guidance and allowing them to corrupt themselves through poor choices, then punishing them for disappointing him. This is certainly a good description of how Enigwa treats his children, the gods. In the last blog, I suggested the Kibbes had created a great myth for the Enlightenment: a myth for secular humanism. The gods experience temptation, fall, wreck the planet and meet with divine judgement. There's no repentance, only Hell or Banishment. Then they're gone. Humanity and its sister-species are left in possession of a ruined world, like tenants-turned-homeowners after the bank forecloses on their landlords. Tolkien conceives humans as bound to God through the inscrutable intimacy of Death and uses his Elves to explore ideas about what an Unfallen Humanity would be capable of (and therefore what fallen humans should aspire to). The Kibbes conceive humans as the product of an unguided evolutionary process, perhaps set in motion by God, but not controlled or monitored by him. In the Kibbean mythology, Death is simply the end and the worst thing there is. The shortcomings of the gods expose the destructiveness of religious ideologies: Berethenu, Grom and Marda are not viable role models. Religion was perhaps meant to instruct and shepherd humanity, but it failed in that and actively abused people until finally losing its grip with the advent of a godless world.

The mythological is political Of course a good myth doesn't have just one single interpretation (that would make it a mere allegory). There's a historico-political strand to Tolkien's mythopeia and a surprising (and creepy) political subtext to the Kibbes' mythopoesis too. Tolkien's Middle-Earth is meant to be our Earth viewed through a mythic lens. The parent civilisations of Classical Antiquity (Numinor) and Biblical Israel (the Elves) are represented as devolving into the murky Dark Ages of lost Arnor and waning Gondor. Gondor is Byzantium, the successor state to Greco-Roman civilisation and Biblical Israel. The Dunedain Rangers and their wards, the Hobbits of the Shire, represent the barbarian peoples of Northern Europe. They haven't inherited the physical accoutrements of the golden age cultures, but they are the custodians of its true values (liberty and Christian conscience). That's why "all that is gold does not glitter" in Bilbo's poem. Tolkien's understanding of Christian civilisation is pretty chauvinistic. Modern historians will point out that Islamic civilisation (very much 'the bad guys' in Tolkien) is just as much the custodian and conduit of Classical and Biblical culture as the Normans, the English and the Franks. The Kibbean myth can be interpreted historically too. Do the gods represent the imperial and theocratic powers of the Old World? Is the Banishment the First and Second World Wars, which toppled their empires and brought about the emergence of republican America, with its separation of Church and State? Berethenu is the British Empire, Crom is Soviet Communism and Necros is Fascism. Humanity, in this reading, means Americans. I feel pretty sure the Kibbes intended no such thing, but their myth does have an unpleasant aspect to it. I mentioned before that, for the Kibbes, Humanity is the ur-species; the Elves and Dwarves, the Ghantus and Merikii, all the lizard-folk and weasel-folk, they are all mutated Humans. In a sense, they are to Humanity what Tolkien's Orcs are to Elves: blasphemous remodelings of the original. Nothing could be further from Tolkien's thought, where the Elves are the Firstborn of Iluvatar and the other rational species (hnau as C.S. Lewis calls them) such as Dwarves and Ents are the independent creations of the Valar. Each has its own integrity and destiny. Not so in Juravia, where Humans are the true form and the other races are simply knock-off copies. Gary Gygax referred to the PC races in D&D as "demi-humans" but in Forge they really are demi-humans. Then you look at the illustration on p12 and - oh dear! - it seems that "the image of Enigwa" isn't just Human, but white people. Then you wonder, what about the lesser, corrupted races, the intellectually challenged Ghantus and the lizard folk and the ghost-faced Dunnar: who are they representing? Awkward... Of course, the Kibbes didn't mean to stumble into the back parlour of scientific racism, with its categorisations of 'lesser races' set against a White European norm. They were just weaving an entertaining tale, a "fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus" as Ron Edwards says. But it does go to show how loaded myths are, and how perilous it is to go tinkering with them. Easy to resolve. I like to imagine that the Kibbean myth in the Forge rulebook is just told from a human-centric perspective and that the Elves claim that they were the original species and the Dunnar claim no, they came first, while the Jher-em think everyone is descended from them. The true appearance of that original species, created by Enigwa and his divine children in a rare moment of harmony, will never be known.

Previous posts discussed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic and analysed its apocalyptic mythology, in which the gods are all banished or consigned to Mulkra (Hell). This mythology, which gets pride of place at the very start of the book, was subjected to Ron Edwards' withering critique about fantasy heartbreaker RPGs indulging in "dumb names" and "un-fun strictures" for clerical characters. Edwards also complains that, despite their enthusiasm for myth-making, these games don't develop fantasy religion any further than a "direct correspondence with player-character options (as opposed to societies or organizations)." In other words, the myth-making just offers an explanation for fantasy races and clerical spells, but gets forgotten about as soon as this is over and done. Let's take a look at that. Life after the Apocalypse The Kibbe Brothers make a substantial and rather imaginative effort to sketch out a fantasy mythology for Juravia, involving a benevolent but absentee Creator and a family of flawed and compromised divinities, culminating in an apocalypse where the deities are judged, found wanting and banished. The implications of this are huge. Most fantasy mythologies - and many real world ones - propose an apocalypse at some future point. The Norse anticipated Ragnarok when the gods will fight the giants and lose. The Aztecs feared something similar and made blood sacrifices on an industrial scale to delay it. The word 'apocalypse' means 'revelation' and is the original name for the Book of Revelation in the Bible, an obscure rant in uncouth Greek where a prophet named John describes (with great relish) the ghastly things that will accompany Christ's Second Coming in a series of mind-bending dreams involving giant angels, many-headed monsters and environmental catastrophes.

The implications of this are huge and not just for who clerics get their spells from. Consider the explanatory power of religion. In ancient cultures, disease and adverse weather, crop failures and pestilence, these were explained by the activities of the gods, either through their negligence in making the world secure against chaos or their active malevolence. That's why you prayed and sacrificed: to get the divine 'on side'. This affected social structures. Society was set up to mirror a divine order, with a monarch supported by a priestly class, receiving authority from the gods to rule and resist chaos as their semi-divine representative or partner. Defying the ruler was defying the gods and siding with the powers of chaos, disorder and death. This focus on divine order doesn't just lead to rituals of kingship, titles and authority; it imbues the calendar with mean, allocating feasts and fasts to different seasons and drawing communities together to reenact the great myths in worship and art. Social order emerges from this and also social distinction: tribes that honour strange gods and indulge in senseless rituals are the 'Other' and conflict between tribes becomes part of the divine order too: warfare becomes a religious duty and death in battle a religious sacrifice. Now let's look at Juravia. What authority can kings and princes cite when some enterprising peasant asks (Monty Python style), "Well how come YOU get to be king then?" What institutions exist to prop up their rule with a claim to possess, not just might, but right? How should the inhabitants start to regard each other, now that it is known as an objective fact that their differences of culture and race (bird people, reptile people, giant one-eyed apes) are the result of self-interested power-grabs by a clan of squabbling super-beings who were all equally criminal in their actions. If praying doesn't solve anything, but the world still contains danger, bad luck, unfairness and outright wickedness, what are thoughtful people supposed to do about it? Actually, it's not hard to answer that. You only have to look at our world for answers. We too experienced a widespread cultural collapse in confidence in religion to provide the rationale for politics, social order and morality. It was called the Enlightenment. Life after the Enlightenment The Enlightenment roughly corresponds to the 18th century in European history and involved the light of reason and science driving out the darkness of tradition and superstition. There were lots of causes. The Protestant Reformation had helped make religion a private rather than a public matter and the bloodcurdling Wars of Religion shaped a view that God had no place in politics and perhaps no place in ethics either. Science arose to claim an alternative explanatory power to religion and leaps in technology seemed to validate scientific claims to understand the true nature of the universe. Forge's legendarium has similar forces at work. The God-Wars serve to discredit the gods and their worship, revealing that the gods were neither wise nor good and that they are no longer able to answer prayers. After the Banishment, mortals work out the principles of magic and learn to cast spells without divine assistance: a close analogue to the rise of science. Magic seems to be a natural (and morally neutral) force in the universe which can be manipulated by those with the intelligence, willpower and the right tools. The gods were just better at it than anybody else. The thinkers of the Enlightenment and subsequent centuries were faced with the problem of living in an imperfect and unjust world, without the assurance that God ordained it to be this way or would intervene to improve it. This is similar to the inhabitants of Juravia, left with a world with all the normal dissatisfactions (poverty, disease, inequality) plus marauding monsters. Fantasy Democracies and other solutions The most influential solution proposed by Enlightenment thinkers was human rights and democracy. In the absence of God, we have to be gods to one another and treat each other as gods. Every individual is accorded a transcendent worth and their consent (in some form) is the only ethical justification for the exercise of power and the continuance of unequal social arrangements. You would expect a world like Juravia to start throwing up democratic republics, where having the status of a rational agent (regardless of your appearance: bird-person or one-eyed gorilla) entitles you to vote. These republics wouldn't necessarily be very stable or even peaceful places. Democracies can be fissiparous and inclined to go to war, especially against non-democracies. You would expect slavery to be a raging controversy and some races might be unfairly deemed 'irrational' and unworthy of the franchise (I'm talking about those dimwit Ghantus). But democracy isn't the only Enlightenment solution. The fact that democratic republics can coexist so easily with the unjust social arrangements that preceded them explains why some people find them no solution at all. Communism offers another way, especially since the Banishment has created a Year Zero and an opportunity to cast down and re-make all social institutions. Agrarian fantasy societies might find Communism much more amenable than democracy, especially if they have to knit together different (and formerly inimical) races. It's easier to get the orcish Higmoni and the avian Merikii to coexist if you take all their possessions off them and redistribute everything. I imagine the frail but empathic Jher-em weaselfolk would excel as Communist commissars. The daylight-hating, magic-detecting Dunnar would rise through the ranks as well, leaving Elves and Dwarves to toil in the mines and collectivised farms. Then there's ethno-nationalism; let's just call it Fascism. Even if the gods are losers and now ineffective, having a specific creator binds fantasy races into a shared narrative, having a place where they belong and a way of life that is ordained for them: they are not just a species but a Nation. "We are Merikii, the People of Marda, and we were granted this land." Nations need borders and a strong sense of who is in (your compatriots) and out (foreigners). At its best, this produces communities with a powerful sense of identity and distinctive culture that is not subject to any sort of rational critique. At it's worst, there's institutionalised racism, enslavement of lesser species and genocide. Finally, there's the true flipside to the Enlightenment: religious fundamentalism. Not everyone accepts the gods are gone, no matter the evidence. Fundamentalism thrives on conspiracies and messiahs: either the gods are hiding themselves (as a test of faith, no doubt) or are shortly to return (to reward those who stayed loyal). Fundamentalists hate the democratic republicans, Communists and Fascists equally: they've all replaced religious worship with a false idol (the will of the people, the common good, the nation). In Juravia, where specific gods created specific races, Fundamentalism might coexist with some forms of Fascism. Maybe the Sprites await the return of Omara to rule over the pastures where she established her little people. In return, the Enlightenment political institutions distrust Fundamentalism. Democracies try to lock religion out of politics (either with a strict separation of church and state or by neutering religion as an established church that serves the state); Communism tries to expose it as a sham; Fascism might patronise some local cults while persecuting other foreign ones. Outright Atheism emerges from this debate. After all, why suppose the old stories of the gods are even true? Maybe Necros was just a way-powerful Necromancer and Dembria an Enchanter. They bamboozled people into thinking they were divine then got their comeuppance. "I'm sure there's a magical explanation for all this, Mulder." Dembria (Enchantment), Kitharu (Nature) and Marda (Beasts) Where does that leave the 'churches' of Berethenu and Grom? After all, these cults have some evidence (in the form of clerical spells) that their gods are still real even if they don't intervene. As sketched out above, some states will try to privatise these cults (whatever you do in your own time...) and others will assimilate them (this document makes you a state-licensed activist of Grom) or repress them (was that an act of ideologically-unsound magic, Friend Citizen?) and in some ethno-nationalist enclaves the cult IS the state (the Dwarvish See of Berethenu welcomes careful waggoners). Atheists will regard 'divine magic' as a hoax: ordinary Pagan Magic with delusions of grandeur. Of course, for ordinary people, there's ordinary superstition. It never hurts to offer a prayer to Kitharu before a sea-journey: if the god still has the power to make it tempest-free, so much the better; if not, what did it cost you? But I can't help feeling that a world like Juravia would be intolerant of such things. Once you reject religion, you don't tend to retain an affection for it, even in its quaintest forms. Since Kitharu infested the deeps with sea monsters and then cleared off, leaving the mess behind, I doubt sailors or the rulers of maritime empires would be sentimental about him. If you want a safe voyage, hire an atheist Elementalist; if you want to tell yourself comforting lies about Kitharu, stay on land. The culture of moderation and litigation The Kibbes' mythology seems to teach other lessons its writers don't appreciate. It condemns any form of extremism. Left to their own devices by Enigwa, the gods pursue their own agendas, becoming more and more extreme until, unable to compromise, they go to war. Obviously, Grom and Necros are the villains, but the tale of Berethenu is poignant. The god of Justice, Berethenu breaks all the laws he was trusted to uphold. He goes to war on the Triumvirate, he shapes humans into his Dwarvish servitor race, he teaches magic to mortals. Of course, he does so for high-minded reasons, but so what? When Enigwa pronounces judgment, Berethenu's own inflexible scruples make it impossible for him to repent: he condemns himself to eternity in Mulkra. The moral: there's no ethical difference between a monster like Grom and a paladin like Berethenu; both end up in the same place. One imagines that, even centuries later, the citizens of Juravia feel discomfort around a Berethenu Knight. Sure, it's nice that they give to charity. But the defining myths of this world condemn what they stand for. The myths also condemn laissez-faire individualism. Enigwa is culpably irresponsible for leaving humanity at the mercy of the squabbling gods. If the gods themselves cannot be trusted to run the world without the firm hand of higher authority guiding them, what chance do ordinary people have for making the right decisions unassisted? One suspects Juravia is a world of authoritarian regimes where people look to strong leaders and distrust liberalism. Even democratic republics can be authoritarian, especially if they are intensely legalistic. The law makes a great surrogate for religion in secular societies because it tries to do the same thing as religion: establish order and the limits of what is acceptable, create the illusion of control over the vicissitudes of life, pronounce judgment by rewarding the virtuous and punishing the wicked, connect people to the past through precedents and each other through contracts. I wouldn't be surprised if Juravian adventurers need to be legally recognised professionals, rather Elizabethan players, subject to the bureaucratic whims of a Master of Dungeons who hands out and revokes the licenses to plunder any particular tomb, cavern or mine, Or just ignore it Ron Edwards notices that Forge Out Of Chaos ignores all of these considerations. He actually takes it as a point in the game's favour that "this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." The Kibbe Brothers seem to bear this out. No sooner have they described the Banishment than they are alluding to the persistence of entirely conventional religion in Juravia. Apparently "sailors and coastal provinces hold festivals in [Kitharu's] honour" (nothing strikes me as less likely) and "the Festival of the Eclipse is still held in [Dembria's] honour" (weird, since Dembria's blotting out the moon is what unleashed the undead upon the world) while "holidays and ceremonies are held in [Omara's] honour" (fair enough, farmers need holidays, but why would they honour a goddess who cannot guarantee anyone a good harvest?). The World of Juravia Sourcebook (2000) makes it clear that conventional polytheistic piety holds sway in Juravia. It's like the Apocalypse never happened. But I like the Kibbes' apocalyptic myth - or bits of it anyway (I'll discuss the unfortunate bits in the third and final blog in this series). It seems to me that there ought to be a fantasy setting properly based on it.

Maybe I'll end up designing it myself... In a previous post, I analysed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic, used by the worshipers of Grom and Berethenu. This led to details about Forge's odd mythology (these are the only active deities and both are imprisoned in the subterranean fiery hell of Mulkra) and Ron Edwards' observation that it is typical of 'fantasy heartbreakers' to belabour mythological backdrops but ignore the role of religion. To be fair, of all the heartbreakers that he reviews, Edwards concedes that "the best of the bunch is Forge: out of Chaos, probably (as I read it) because this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." Edwards sketches out a brief checklist of the way these games travesty religion while obsessing over mythological settings:

Let's see how Forge measures up to the first two; the third will have to wait until the next blog. The God-Wars The Forge rules open with a mythological treatise, explaining how the Supreme Being (named 'Enigwa') created the world and ordered it to be beautiful and harmonious. Enigwa then snoozes (having become Enigweary?) and his children, the gods, are left in possession of the paradise he has bequeathed them. The gods start off perfect too, but they become more differentiated as the ages pass, with some developing selfish or aggressive traits. The Supreme Being is disturbed by this discord and, I suppose, Enigwakes. He draws the gods together in fellowship to create Humanity and then commands the gods to be mankind's instructors and guardians, for Man shares the best and worst traits of the gods. Then Enigwa disappears, off to create new worlds (his Enigwork?), strangely blind to the trouble he has set in motion. The gods immediately fall out and a triumvirate forms: Necros the god of Death teams up with his brothers Grom the god of War and Galignen the god of Disease. Grom starts creating his own servitor races by mutating humans: the orc-like Higmoni, the Klingon-inspired Berserkers and the one-eyed gorilla Ghantu. After a polite pause to register their shock at this impiety, other gods follow suit: Dembria, goddess of Creation, creates the albino Dunnar; Katharu, god of nature, creates the lizardy Kithsara; Marda, goddess of Animals, creates the avian Merikii; Omara, goddess of harvests, creates the half-pint Sprites; even virtuous Berethenu, god of Justice, creates his loyal Dwarves. I'm not sure who creates the wheezing weasely Jher-em; Marda, I suppose. The Elves aren't attributed either, but Terestar the god of Time appeals to me as their creator. The gods go to war, tearing up the landscape. Marda is particularly wrathful, creating monsters and Dragons to defend her pristine wilderness. Necros figures out how to create the Undead to be his creatures. He tricks Dembria into creating the moon to blot out the sun, so that his undead army can dominate the lightless world. Then, when his sister Shalmar the goddess of Life pleads with him for peace, he murders her Enigwa returns to judge his creations and he isn't happy: his Humans have been mutated into other races, the landscape churned up and rearranged, Shalmar dead, the moon blocking out the sun: it's not pretty and the Supreme Being is Enigwrathful. He pronounces judgement on Necros, flinging the death-god into "the endless void." Grom gets dropped into the fiery depths of Mulkra for his crimes. Berethenu has the chance to repent but is too noble to accept forgiveness: he leaps into Mulkra to be imprisoned with Grom. Enigwa gathers together the remaining errant gods and takes them away with him, leaving the world of Juravia to recover from this divine ruckus. The various races are left to pick up the pieces in a god-free world. They reconstruct the principles of magic but, since these powers no longer come directly from gods, Pagan Magic is uncertain and has nasty side-effects. Down in Mulkra, Grom and Berethenu seize moments between burning in eternal agony to invest their worshipers - Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors - with Divine Magic. There are rumours that the gods occasionally sneak back to Juravia when Enigwa isn't Enigwatching and the monsters and undead horrors unleashed during the Great Wars are still out there, causing trouble. All this rationalises a fantasy world with monsters, races and magic, Dumb Names Guilty as charged, but it's not all bad. If Enigwa is a dumb name for the Supreme Being then chain me to the wall. It's got 'enigma' in it but the W has been flipped, see? The overall effect hints at something African, which is great. There are a lot of GFNs (Generic Fantasy Names), just syllables with -a or -ia or -ar added on the end. 'Necros' is lame, being filched from the Ancient Greek nekrós meaning 'corpse.' I'm sympathetic to the Tolkien Conceit, that fantasy names are just translations into familiar English of words that are really in other languages, so Peregrin Took was really "Razanur Tûk" in Westron. But if you're going to do that, be consistent. Shalamar should be named after the Greek for 'life' which is Zoe, Grom should be Polemos, Galignen should be Nosos and Marda should be Therion. Fine names all. Some of the names have a whiff of poetry to them. Galignen has connotations of 'malignant' which is clever. I like the -u names Berethenu and Kitharu, which suggest (to me) something Babylonian or perhaps Romanian or East Asian. Grom is a near-steal from Robert E Howard's Crom, the war-god Conan respects (I was going to say 'worships' but that's going a bit too far), and in turn adapted from Celtic myth. But it's all a mad jumble really and not in a good way. Over on Zenopus Archives, there's a 'Holmes Random Name Generator' that creates fantasy names extrapolated from the quirky imagination of Basic D&D author Eric Holmes. These names may be random but they're not GFNs: Chor Paldon, Zoque Kar, Losho the Blue, I could do this all day. Try it yourself: These names are random collections of syllables, but they're still evocative. Crucially, they're not European in flavour. They sound like they're from a slightly alien fantasy land: not Marda but Mardreb, not Dembria but Drebael. Thomas Wilburn slams Forge for (among other things) starting off with 10 pages of myth-making before we get a content page, never mind rules: "mythology belongs in a background section in the main text, not at the very front where the reader has to wade through it just to get to the game." But the trend for '90s RPGs to kick off with thematic fiction or campaign setting before introducing the rules was well-established long before Forge came along. No, I don't object to the positioning of mythology at the start of the book and it's well-written: in fact, it's the best-written part of the whole book. I just wish the Kibbe Brothers had knuckled their foreheads and come up with names that were genuinely evocative or thematically consistent . What cultural setting do these deities connote? Five minutes of Google-fu (or half an hour with a decent encyclopaedia) prompts suggestions like this: This harmonises the gods' names (I like that -u ending and -ara as the feminine suffix is more interesting than plain -a or prettified -ia) and Nergu re-names Necros along Babylonian lines. Just sticking an O- prefix in front of Grom works wonders (and connotes 'ogre'). Why would all the races use the same names? The creatures of Kitharu and Mardu get a synthesis of Babylonian and Yoruba names and the 'Grom-folk' (Higmoni, Berserkers, Ghantu) get Japanese-inspired adaptations. I think the Dunnar would have Celtic-style names (reverencing Dembara and Dobuna, Berethenu as Berethos and Grom as Crom) and let's go with Norse-style for the Dwarves (re-titling Berethenu as Borothor and Grom as Grotun) and Greek-style for the Elves (Berektor and Grotos). Names do amazing things: they imply a world. Un-fun Strictures No surprises here. Grom Warriors and Berethenu Knights both have to follow an honour code. For Grom-ites it's a simple barbaric code of never running away, fighting face-to-face and taking part in a demented yearly rally. Berethenudians have a chivalrous equivalent that gets more restrictive as they advance: eschewing armour and fighting fairly. From a roleplaying perspective, these strictures are intensely external to your character's identity. It's frustrating for Berethenu Knights that they cannot wear plate mail and have to give away a tithe. Not being able to attack from behind makes a few combat encounters slightly more awkward than they have to be. But you can 'tick the boxes' with these requirements and play your cleric just like all the other characters. What we don't learn is what foods are forbidden, what clothing must be worn, what sex acts are condemned, what daily rituals must be enacted. In other words, what is like to live in the service of this god?

The oddity is not that clerics suffer such strictures, it's that no one else does. There's a tendency for lay people to adopt the strictures associated with holy folk in order to make their own lives more holy. Over time, these strictures become the sort of codes of dress, diet and sexuality that make up a religious lifestyle. If Berethenu Knights tithe and behave chivalrously, then this sort of chivalrous, charitable code will spread to other people who don't have magic powers to lose. If Grom Warriors fight one-on-one and boast of their kills, then a culture of dueling and boasting will also become normative in society. One way of handlig this is through Benefits & Detriments (pp17-18), which currently involve trading of advantages (being tall or stocky or having a resistance to poison) against drawbacks (arachnophobia, deafness or being one-eyed). Religious strictures make good Detriments and violation can be punished by removing experience checks or imposing bad luck (-4 on next Saving Throw). It's interesting to reflect on what else Grom or Berethenu expect from followers. Are Berethenudians vegetarians or virgins? Or are they expected to marry and have families? Are Grom-ites forbidden to marry or acknowledge their children? In the real world, sexual abstinence is the distinctive feature of religious observance yet it gets no mention in RPGs like Forge. Distinctive dress codes and grooming are features of real world religions: Jewish peiyot (side-curls) and kippah (circular head coverings), beards in Islam, turbans in Sikhism, bindi (forehead dots) in Hinduism and Jainism. Often, these create a more abiding stereotype of a religion than anything the members actually believe or do. How does one recognise a Berethenu Knight? Do they wear sashes, turbans, shawls or phylacteries? Do Grom Warriors shave or wear hair down to their knees? Of course, to answer these questions, you need to have a cultural conception of the fantasy world these people inhabit. Is it Northern European, Middle Eastern, Asian or African in tone? In order to decide whether Berethenu Knights wear turbans or kilts, you need first to consider what sort of ethnicity they represent. Unsurprisingly, the Forge art represents 'Humans' as white Europeans (e.g. p12, p86, cloak, trousers, cean-shaven, mullet). That's disappointing (and not just because of the mullet) and it will take another blog to explain why.

This leads into the most important topic, which is how a fantasy world is shaped by its religions - a point widely ignored in games like Forge - and I'll get stuck into that in the next blog.

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

Hedgerow Hack

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed