|

DM's Guild is a fantastic resource if you're looking for D&D scenarios with a high quality bar. Babbling Wizard has a set of scenarios and mini-campaigns and I looked at Secrets of Leaf Grove because it is a module that can progress a small group of D&D characters from 1st-4th level over 4-6 sessions. Secrets of Leaf Grove is pay-what-you-want for the PDF download Leaf Grove is the sole work of David A. Hughes and an attractive piece of work it is too: beautifully laid out, some on-point colour art, attractive maps, clear stat boxes and information captions and a lucid and (almost) typo-free style. At 40 pages, there's plenty here for a DM to be getting along with, but it could also be used as pick-up-and-play if you want to jump straight into the first scenario. SPOILERS AHEAD I'm afraid: I want to talk about the plot (although, to be fair, the front cover gives away the nature of the main antagonists). Welcome to Leaf Grove Leaf Grove is an idyllic rural community surrounded by corn fields. If this were a Stephen King story, the children here would have murdered the adults long ago. There's a nice village hall and the 'Corn & Cob' Tavern that can seat seventy people (so it's half the size of my local Wetherspoons). There's a vigorous local democracy that entrusts power in three Councillors named Thorpe, Berry and Linwood. Everyone is sturdy and prosperous. It's like Maycomb, without the racism, or Bedford Falls, if Henry F. Potter didn't own the town. Small town America: To Kill A Mockingbird's Maycomb and It's A Wonderful Life's Bedford Falls David A. Hughes may be British, but this is a very AMERICAN setting, with its democratic traditions and vast cornfields and homely goodness. The villagers are holding a local festival when the scenario starts and you can't help but imagine the Fourth of July, with fireworks and corndogs. But, like most narratives set in such small towns, there's a darkness behind the facade. No, not racism or robber-capitalism, but a conspiracy nonetheless, a conspiracy aimed at benefiting the town that has unwittingly drawn monsters into the community. People have been disappearing under odd circumstances and the PCs have been invited here by Clr William Berry to investigate. The players enjoy the fun of the fair and meet the locals, some of whom are unaccountably hostile or secretive, before hiking out to Miles Hogan's farm to investigate his missing wife Alice and the odd disappearance of Clr Linwood. Investigating the conspiracy in a small village is a plot hook that goes right back to the good old days of D&D. The Village of Hommlet (Gary Gygax, 1979) hid evil agents in its midst and Against the Cult of the Reptile God (Douglas Niles, 1982) pitched the players into a village that was in the process of being subverted by a monster cult, with more NPCs going over the reptile god each night, evoking chilling Invasion of the Bodysnatchers paranoia. Innocent-looking fantasy villages harbouring dark conspiracies go back to the roots of D&D Writing a scenario in this genre puts you up against the stiffest competition there is. David A. Hughes' solution is to double down on the homeliness. There's no cultic conspiracy, more a sort of misunderstanding. One of the Councillors is a Wererat trying to ingratiate himself into a Lycanthropic gang by preying upon the community, along with his band of Kenku outlaws who have been abducting anyone who gets suspicious. The Kenku have been over-enthusiastic in their remit, the PCs have arrived to poke about, and the Wererat is spooked and does a runner. The plot rolls out from there. Critique A lot of scenarios stand or fall by their setting. Michael Thomas' Necropolic of Nuromen creates a low-level setting with Camlann set in a fairy forest that is steeped in otherworldly resonance. David A. Hughes' setting goes to the other extreme: Leaf Grove is so cosy it could be nestled at the foot of Walton Mountain. That is not necessarily a bad thing. The decency and simplicity of Leaf Grove and its innocent citizens stands as a contrast to the bestial Kenku and corrupt Lycanthropes in their midst. Moreover, if you're American, the setting perhaps won't strike you as so un-medieval. I'm reminded of the Apple Lane (Greg Stafford, 1978) supplement for Runequest, which located Glorantha's wild barbarians a township that could easily have had Tom Sawyer for a resident. There's a place for the low-key and the folksy in fantasy RPGs. I balk a little at medieval villagers with names like 'Darwin' or taverns named 'Corn & Cob' but the author leans into this. Later in the scenario, the village will come under attack and its fundamental homeliness will be important for giving the players a motive to fight (against stiff odds) to defend it. Dastardly Bird People The first scenario sends the PCs off to find Alice Hogan, who disappeared while fixing her scarecrow. I wonder if the allusions here are intentional, and not just to Children of the Corn. Has Alice been swept away to Oz? Slaughtered by the Jeepers-Creepers monster? I suspect that the players will be far more alarmed than they need to be. The truth - that the Kenku have bundled her into a nearby abandoned shrine - will probably come as a let-down. But the clawed footprints of something that seems to have dropped down from the scarecrow's post and made off with Alice will have players scanning the sky for the indestructible Creeper's reappearance, not looking underground for malevolent canary-people. Underground we must go. There's a nice scene where PCs descend on ropes into a long-abandoned tunnel. There are monsters to scrap with and good advice for making the setting as eerie as possible as the Kenku call to one another and imitate voices. There are some surprise undead locked away in a side room. There is Linwood the Wererat, pretending to be a prisoner, till he gets the drop of the PCs and can fully rat-out. At this stage in their careers, PCs will struggle to overpower a Wererat unless they were prescient enough to bring silver daggers (to be fair, in any group of players, there's always one..). Critique As with Leaf Grove, the problem here isn't what the author delivers, so much as the expectations he allows to rise first. The missing woman, the endless cornfields, the sinister scarecrow... that seems like a set-up for a brilliant Call of Cthulhu mystery. The Kenku in the tunnels are a disappointment after that. It's like finding a coffin with a mouldering corpse impaled by a stake through the heart, then learning you have to do battle with Kobolds. For all that the Kenku lair has artful layout and good atmospheric tips as well as an investigation, it's like a film that can't live up to the promise of the trailer. I'm not a 5th edition gamer, so I can't comment on the threat/reward balance. I know if this were 1st edition AD&D, a bunch of Kenku would be deadly opposition for first level characters. By old-school standards, the treasure is stingy. But the stat boxes detail the monsters as easy/medium threat and I presume the encounter is such that, when they leave it with the prisoners freed, the PCs will be ready for second level. They'd better be. Werewolves are coming. Wolves in the Sheepfold The Werewolves arrive in Leaf Grove to reclaim their buddy, Linwood the Wererat. They swagger into town like Eli Wallach in The Magnificent Seven, with a bunch of demands, then bust into buildings, terrorising people. The PCs have to barricade themselves inside and deal with the monsters that get in. This is a great scene and, once again, pure Americana. Small town detail that seemed twee or un-fantastical at the outset pays out now, because this is a Western, with the PCs defending the range, like Shane or John goddam Wayne, against the furry banditos that roam up and down the main street and jump through windows into the cantina. Calvera (Eli Wallach) menaces the innocent villagers in John Sturges' The Magnificent Seven (1960). Don't watch the recent re-make. True to the playbook, Marina (check the Latina name) who runs the cantina shows her mettle against these gangsters. She's a Lycanthrope too, a Weretigress with a heart of gold, and she flings the mutts about and chases them out of town. Critique Look, I love this scene. Werewolves super-outclass PCs at this level, but the author provides a bunch of options to scale the difficulty, based on the PCs' toughness and access to silver weapons. They might end up just scrapping with ordinary Wolves while the proper lycanthropes menace the NPCs. The arrival of a super-powered NPC deus ex machina will be very welcome by the end of this. This is going to be the most memorable scene in the scenario (with one possible rival later on) and a gleeful DM will want to stretch it out for maximum drama. We want children in peril. We want the townsfolk to rally armed with household utensils. We want a werewolf on fire to fall out of an upstairs window and roll about howling in the dusty street. Pure film! Since this is the beating heart of the scenario, which brings the true threat into focus and establishes what the PCs are fighting for, I think it's a shame the Western motif wasn't grasped more firmly. The tavern makes more sense as a Cantina. There ought to be a drunken sheriff and a feisty schoolma'am. Everyone should have Latin-inflected names. We should feel like we're in a Spaghetti Western, not The Shire. But that's just my imagination getting fired up. Druidic Double-cross Marina knows the truth about the Lycanthropes - their leader Vrell passed his Weretiger curse onto her - but not where the monsters are based. To find that out, a trip into the woods is needed, to consult a Halfling Druid. This part of the scenario offers a less linear plot. There are random encounters in the forest, an optional encounter with orcs and half-ogres and a final showdown with the boss Ogre, before the Druid turns up with a side quest: rescue a relic called The Leaf Scripture from a spider-infested cave. There's a double-cross, because the Druid isn't who he appears to be, but the PCs will end up with directions to the Lycanthrope Lair, by either a safe or a dangerous route. Critique These side-quests bedevil RPG video games and are a fixture in TTRPG modules too, so I shouldn't complain to find one here. They pad out a storyline, allowing PCs to level up or pick up magical weapons or allies, before reaching the final showdown. They add an air of verisimilitude, because life is a winding road with cul-de-sacs and double-backs, so they dilute the sense of being railroaded to a predetermined outcome. They create a sense of a wider world with things going on in it that don't pertain solely to the PCs' concerns. The problem is, they break up theme and atmosphere, and that's what this digression does. The Leaf Scriptures haven't been foreshadowed in previous investigations and the fate of Eldon the Druid lacks punch because he's not been prepared for. Indeed, the players probably never learn what befell him. Coming after the gripping Werewolf Attack on Leaf Grove, a skirmish with big bugs in a cave system feels like workaday dungeon-bashing. Don't get me wrong: this side-quest isn't bad. It's just a bit unmemorable. But fear not, because better things are ahead. The Weirdness of Wolf Tower If the PCs get the safe route, they arrive at a magical tower where the were-beasts are holed up. Getting past the Wererat guards without alerting everyone inside requires some ingenuity. Alternatively, the PCs might arrive by the more dangerous route, descending into a rocky gorge that's the territory of a Gorgon. There's a great build-up to this. The gorge is an eerie place. You notice the odd rocks. They're like fragments of larger stones. You see human features: fingers, eyes, mouths, in the shattered statues. Then the massive Gorgon comes snorting out of its lair. It's a great D&D moment, worth the price of admission all by itself, and the players get rewarded for the risk by finding a secret entrance to the tower down here. The Tower itself is an entertaining skirmish with were-critters, lent an extra twist of weirdness by the architect's magical legacy: the stairs between floors don't connect spatially, so characters move to unexpected levels. This could prove hilarious if the party get split up, or terrifying if the occupants are alerted and use the bizarre geography to ambush the PCs. The final showdown with Vrell the Weretiger is wisely curtailed: he will surrender if wounded, so that he can enjoy vainglorious threats and mind-games before being hauled off to face justice in Leaf Grove. Showdown, baby: roll initiative. Critique This is a solid climax. The Gorgon Gorge is a great cinematic moment. The layout of the Tower throws an Escherian curveball at attempts to map the place. Vrell is an entertainingly despicable villain. And yet, it's just a big fight, really. In dealing with the Kenku, there was a rescue mission; this is search-and-destroy. That's valid. Lots of players love it. But there's no option for players who prefer trickery or diplomacy or were hoping for spine-tingling mysticism. The Lycanthropes aren't opening a gate to the Feral Realms or wrestling with their humanity. They're just a bunch of chaots waiting for the PCs to bring the cleansing (silver) sword. Final Thoughts Secrets of Leaf Grove is a solid D&D adventure. Really solid. It offers new PCs a setting they can easily relate to (especially if you're American), a mystery and a quest, then it ups the stakes, sends you on a wilderness journey and then lets you assault the monsters in their magical fortress. The threats scale, there are opportunities along the way for negotiation and problem-solving and, though the story is essentially linear, there are a few scenes where the players' creativity can determine the outcome instead of the script. What holds me back from giving it more enthusiastic endorsement is that there are moments here that are better than solid, and one scene that is A++ Great, which shows you how much more awesome this scenario could have been. The roof-raising scene is the Werewolf Attack. The inspiring moments are the scarecrow in the cornfield, the chamber of the Leaf Scriptures, the appearance of the Gorgon and the spatial anomalies in the tower. The monster encounters that link these moments together are a little pedestrian. I wish the Dryads had mysteries to tell and lost lovers to pine for, I wish there were Wererats battling with their curse and seeking redemption, I wish Eldon the Druid had died a more meaningful death to a more satisfactory opponent, I wish there were precipices to hang from and slaughtered pioneers to avenge. I wish the forest had more intriguing threats in it than Orcs and Ogres. The setting itself serves its turn by making the players want to defend it. But it has no value as an ongoing base. There are no loose ends in Leaf Grove, no ongoing conflicts or campaign hooks. Once the Lycanthropes are defeated, there's no reason for the PCs to stay here. But that's just me. I'm a romantic who likes messy outcomes. New players to D&D 5ed. will ease right into this adventure. The fright they get when the Werewolves show up at their windows will lend extra tang to the payback they deliver in the tower at the end. Hommlet and the Against the Cult of the Reptile God won't be losing any sleep, but Leaf Grove will be the memorable start to somebody's lifelong love of D&D.

0 Comments

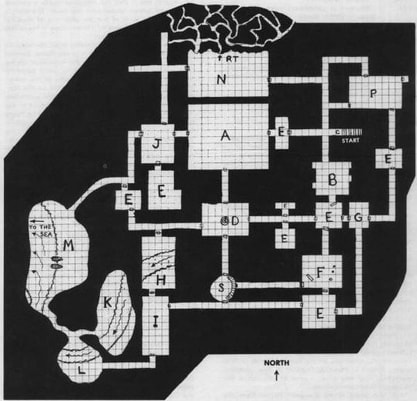

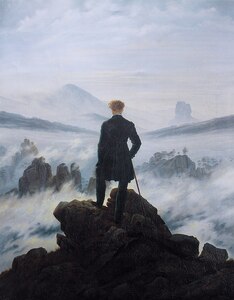

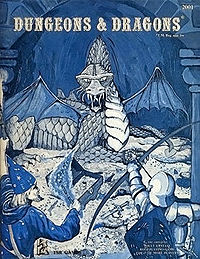

Michael Thomas' Blueholme Prentice RPG introduced Eric Holmes' 1977 Basic D&D rules to a new audience. His Blueholme Journeymanne positions the game as a serious retroclone contender, muscling up against White Box and Delving Deeper for the title of 'Heir to Seventies D&D.'. The last blog reviewed these two: Blueholme Prentice for 1st-3rd level PCs; Blueholme Journeymanne for up to 20th level. Click the images for drivethrurpg links. Blueholme has an advantage over its competitors. They have to draw something coherent out of the jumble of Original D&D materials, picking and choosing their rules and supplementary material and trying to give it a character of its own (I feel White Box succeeds at this; Delving Deeper less so). Blueholme is channeling one man's singular vision of D&D. It has distinctiveness built-in. The trick is to reveal it. The solution is an introductory scenario. So welcome to THE NECROPOLIS OF NUROMEN, Blueholme's first module for starting characters. The contender: Michael Thomas' Necropolis of Nuromen (click image for link to download). The reigning champ: Eric Holmes' Ruined Tower of Zenopus from the 1977 Basic D&D Rules Set. The brief for this is a tough one. Of course, it has to be an excellent dungeon-crawl that will challenge and intrigue experienced players paddling at the shallow end with first level characters but also work well for newcomers. More than that, it has to showcase what's special about Blueholme: how does this version of OSR roleplaying help tell stories that the others don't? The scenario has a collaborative history, emerging from Justin Becker's 'Forbidden Mazes of the Jennerak' campaign, which is being adapted by Michael Thomas into a 3-part scenario series, of which this is the first. This gives context to some criticisms I make later. That Cover Leaf through Blueholme Prentice and you'll see that Michael Thomas has a gift for sourcing public domain art with a fantasy vibe. The cover here looks like an Ayleid Ruin from Elder Scrolls IV, but it's a piece of stunning Romantic art by Caspar David Friedrich, a 19th century German landscape painter with a taste for the spinetingling. He's best known for that one where the chap stands with his back to you on a mountain top, looking down on the clouds. Monastery Ruins in the Snow (1819) - which is going on ALL my Christmas cards from now on - and Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) which seems to be a painting about both nature AND humanity. Friedrich's landscapes defy improvement (that sky!!!) but Michael Thomas gives the whole thing an eerie blue tint, because branding, right? It's a great cover that sets the tone for his game. The Setting The scenario is only 20 pages long, but Thomas devotes the first 4 pages to the setting. This is a bit of a gamble. Some people just want to wrench dungeons out, bleeding, from their settings, like Molam Ram plucking out hearts for Kali. You can do that. Just skip this stuff and go straight to the dungeon. But you're missing out! Don't be this guy. The setting is a distinctive High Fantasy realm. The town of Camlann gets its own map, its mystic porcelain tower, Lady Leika of the Lily and her griffon-riding guards. There are local celebrities, rivalries and gossip. This takes the lightly-sketched idea of Portown and the Green Dragon Inn from Holmes' sample dungeon and improves on it. The Camlann setting has its own magical quality, while rooted in the earthy down-homeliness that's needed to make a journey away, out into the darkness and danger, so compelling. Outside Camlann is the Delvingwood where the local Elves are declining and the Goblins are advancing, turning the fairy forest to evil. This is an evocative setting, with more of Narnia to it than Middle-Earth. A broad grassy road, the Elfway, cuts through the woods but if you leave this highway and enter the trees, why, you're stepping into the Otherworld, crossing Joseph Campbell's Threshold for the Hero's Journey. This is all very nicely structured. Holmes' 'Zenopus' dungeon had a menace to it and Thomas parallels this. Instead of the morally-murky Zenopus, we have Nuromen who's an outright rotter. This necromancer sets up a Chaotic enclave in the woods called Law's End but his gang of villains are blasted by an unspecified catastrophe, doubtless of his own making. His underground Necropolis stands unguarded beneath a 'ghost town' in ruins with the forest advancing over it. As is standard, the PCs are greedy and ambitious dungeon raiders looking for a fortune and a name for themselves. However, Thomas adds a feature that Holmes misses. The PCs encounter the Elves on their way to the dungeon and are tasked with the recovery of a magical heirloom. This gives the players a focus and a sense of dignity to their mission: they're not just looters. Critique I really like this set-up. The tone is very effective: an elegaic sense of decline and lengthening shadows, an evil from the past, a noble mission and a wilderness journey, all set in a fairy tale kingdom with just enough darkness to it to head off sentimentality. It reminds me of the setting sketched out for Jean Wells' Module B3: Palace of the Silver Princess (1981). If Holmes drew inspiration from Robert E. Howard and Lovecraft, then the world of Justin Becker/Michael Thomas feels like it owes more to Lord Dunsany and Lloyd Alexander's Prydein Chronicles. The downside is that this material is not well laid-out. The text starts with the description of Nuromen's downfall, then outlines the geography of the forest, then the set-up in Camlann. There are NPCs and Rumours in Camlann, then back into the Forest we go, with Wilderness Wandering Monster Tables for on and off the Elfway landing us back in the Ruins of Law's End and the abandoned Necropolis. It's an odd structure, involving repetition and redundancy while also allowing you to forget or muddle important material. A bit of editing would help here: Camlann > Elfway > Delvingwood Forest > Law's End/Necropolis is the structure that GMs need. It's a shame that this background material is (slightly) impenetrable, since it encourages careless readers to skip it. A lot of thought has gone into offering low level characters a wilderness journey with real dangers but balanced encounters and a metric ton of theme. Jeff Jones' Dunsany-inspired art also captures the world Thomas is exploring The Dungeon The dungeon is a two-level affair, but it's built to an epic scale. The party have to drop down into a vast shaft - 50ft across and 100ft deep - using ropes that a squad of Goblins have left behind. Deep underground, the PCs move through corridors and chambers carved out of the limestone crag. Holmes' dungeon evoked suffocating darkness, opening out into immense, echoing chambers; Thomas' Necropolis is different, it has an eerie but sinister beauty in its carved murals and looming doorways. There are 20 rooms on the First Level, 6 of them empty and the rest more often interesting than dangerous. A gigantic subterranean courtyard offers a safe hub that the party can branch out from in their explorations. Most of the traps can be avoided with forethought. There are ghosts and illusions and remnants of Nuromen's old spells. Aside from the Goblin raiders, the monsters are largely dungeon pests and mindless undead, but the Big Bad on this level is a nest of Harpies who could easily overwhelm an incautious party. There's treasure to collect but not much: a couple of thousand GP total, so no one is levelling up by clearing this out. There are magical items to pick up, especially for Magic-Users. The highlight of the First Level is the study and workshops of Nuromen himself. There are lots of things for players to tinker with and surmise, plus a few windows into the dead wizard's psyche and rewards for players who can figure out what motivated the old villain. Unlike the opaque figure of Zenopus, Nuromen is present here in spirit if not in body. There are signs of his handiwork everywhere. If the First Level is a slow-paced investigation into long-dead mysteries, down on Level Two things take a turn for the weird and the wonderful. There are 15 rooms, but only 3 are empty, so it's more densely packed and more unforgiving. There are nastier traps (an over-reliance on poison, which I hate!), riddles, some quirky magic items and chilling scenes of evil occultism. Troglodytes will give first level characters a run for their money. The climax comes when the party access Nuromen's Tomb and go up against Nuromen himself, now a very dangerous undead antagonist. The treasure here is stupendous, so survivors are definitely leveling up. Critique The dungeon is beautifully structured, offering players radiating spokes to explore on the First Level while the Second Level funnels them towards an inevitable showdown with Undead Evil. The maps look lovely. They are all tucked at the back, after the OGL pages, which confused me at first. It would be nice if the maps appeared alongside the room keys, making it easy to read off the screen/page and hold a picture of the layout in your mind as you do. Similarly, there's a lot of high quality description, but it's usually mixed in with exposition and mechanics. The Dungeon Key would benefit from introductory descriptive paragraphs for each location: something the GM can read aloud, providing all the visual detail for players, with the GM-only material underneath. It's a pity that the Rumours back at Camlann don't help the players make more sense of what they encounter in the Necropolis. For example, there's Robin the Thief, now turned into a riddling Ghoul and guarding some of Nuromen's treasure. How much better for the PCs to hear the tale of Robin's hideous fate back in Camlann, then recall it here, rather than the GM having to info-dump for Thieves in the party. Other snippets about the Cult of Gamosh and Nuromen's wife and child would make helpful Rumours too. The stinginess of treasures is a problem. Blueholme sets its XP rewards for killing monsters quite low and, in any event, there's not that much combat to be had. It's desirable that at least some of the party be second level by the time they go up against Nuromen. If (say) the Thieves and Clerics are going to get to second level, then a party of 4 needs to earn over 5,000 XP. There just aren't enough combat encounters or valuable treasures to do this. I think doubling the treasure rewards in the dungeon and halving the size of the big hoard in room 25 could result in a party of mixed 1st/2nd level characters going up against Nuromen at the climax. Some of those second level characters will probably lose a level in the fight. 'Nuff said. Alternatively, instead of placing the key to the treasure chamber (25) around the undead necromancer's neck, it could be found instead upstairs in his chambers (12 or 13), perhaps with a map indicating the presence of a secret vault, reached through the caves on the lower level (18). This would allow canny players to access the treasure before they run into Nuromen himself: flight is then the prudent choice. Certainly, when the PCs emerge blinking from the Necropolis at the end, they will feel that they have earned their spurs. More Caspar David Friedrich: Evening (1820-1) makes a great image for the faerie Delvingwoods Epilogue: Bandits, grr-rrr The scenario doesn't end there. Back in Camlann, bandits are up to no good. A breakaway faction of the outlawed White Company is kidnapping merchants. Tracking them back to their cave lair is in order, then bloody retribution. This is a welcome epilogue. The Dungeon itself was mostly investigation, mystery and puzzles, with just a handful of combats, the latter ones very stressful. Some players might be in the mood for uncomplicated monster-bashing as a way to unwind, especially if everyone is second level now. Bandits make great punchbags. Well, guess again. The Bandits all have 6hp, so they're surprisingly resilient. Their boss, Lothar, is a 6th level fighter, also with above-average HP, and he's got half a dozen Gnolls backing him up. There's an Owl Bear in there! The good news is that Lothar is sitting on a hoard that should get all the survivors up to third level. However, his treasure is the only loot in this place, so if the Bandits send the adventurers away with their tails between their legs, they'll have nothing to show for the adventure but bruises. Critique This section of the adventure feels undercooked. The Bandits are well-organised in defense of their lair, but there's no option but to slog through them. Lothar is supposed to be defying the Bandit Prince who leads the White Company. It would be helpful if some of the Bandits were loyalists who would turn against Lothar. There's a prison pit, crying out for a prisoner to occupy it, a useful NPC who knows the caverns and could guide the PCs. As it stands, this side-quest is a brutal skirmish that will probably overwhelm second level characters and doesn't offer much to reward experienced players who want to try more devious or diplomatic strategies. Of course, the party don't have to take on Lothar. They could just rescue the merchants and claim a modest reward. But c'mon now, is that what HEROES do? Michael Thomas confirms his intention that PCs do NOT fight Lothar to the death, but instead try to capture Bandits for the reward (50gp a head!). Blueholme doesn't provide any mechanism for subduing enemies nor does the scenario suggest one, but here's a thought. The GM could rule that, with any group of Bandits, once half are dead, the other half surrender. This makes skirmishing in the caves easier and more lucrative. Alternatively (or additionally) a force of 2d6 1st level Fighters from the Camlann Constabulary could bolster the PCs in the final showdown with Lothar - and Lothar could surrender once he has lost half his Hit Points. Can't get enough Caspar: Cairn in the Snow (1807) is great for the entrance to Lothar's Lair Final Thoughts This is a deeply atmospheric dungeon in a great High Fantasy setting. It's got a distinctive mystical vibe to it that takes its cues from Eric Holmes. It's clearly a Blueholme Dungeon and it promotes its brand. The Dungeon is structured around exploring and investigating rather than fighting. There are treasure troves to pick up but not enough to level up. The massive hoard at the end (should it be found) will level everyone up, perhaps placing Thieves at third level. That feels 'off' - especially considering the climactic battle the players have to endure to get the key. It's tempting to dial back the danger (Nuromen would be quite deadly enough as a Ghoul or a Wight) or shift some of the loot out of the hoard or put the key elsewhere in the dungeon; that way, PCs could retreat to their camp, level up, then descend to vanquish Nuromen or run away from the encounter with him. The problem is even more pronounced in the Lothar epilogue. Lothar's hoard exceeds 10,000gp, so half a dozen PCs could level up from that, but he's 6th level and protected by Gnolls! Part of the charm of Blueholme Prentice is its third level 'ceiling'. Why can't Lothar be a really nasty 3rd level Fighter? Couldn't his loot be scattered throughout the lair so that PCs can pick some of it up during other skirmishes? Alternatively, rules are needed for capturing and subduing the Bandits rather than battling them to the death. These aren't damning criticisms. It's easy to adjust treasure and threat, based on how quickly you envisage the PCs progressing through the levels and how many need to die doing so. GMs will need to make their own minds up about what they expect players to accomplish and whether The Necropolis of Nuromen is supposed to end in hard-won victory, tactical retreat with riches or an ignominious death. However, set all that aside. The scenario has much greater strengths. The journey down the Elfway, into the Delvingwood and then deep down below ground, into the vaults of the Necropolis: this is a deeply memorable start to anyone's campaign and a calling card for Blueholme as an RPG with a distinctive style. Michael Thomas is working on a new scenario that will function as "a real introductory adventure" to Blueholme (rather than just being a low-level adventure): The Shrine of Sobek should be out next year but I hope The Necropolis of Nuromen gets its sequels too. No, not the sensational 1959 Miles Davis album, but the equally seminal 1977 'Blue Book' D&D rules by Dr J. Eric Holmes. I want to review Holmes' treatment by a pair recent retroclone RPGs: Blueholme and The Blue Hack, both by Michael Thomas. If one of these things interests you more than the other, you MIGHT be in for a disappointment with this blog... Holmes' 'Blue Book' rules set has a legendary status among D&D fans, and deservedly. Before Holmes volunteered his services, D&D was a rag tag collection of cheap booklets and magazine articles supplemented by fan products of varying credibility. Since few gamers owned them all, no one who played D&D was really playing the same game and the game itself was pretty impenetrable if someone hadn't shown you how to play it first. Eric Holmes changed all that. His 50-page softback manual set about building the Original D&D game from the ground up, starting with character creation, rules for combat, spells, monsters, treasures and concluding with his wonderful sample dungeon, the 'Tower of Zenopus'. By modern standards of rules design, Holmes' book is cluttered in places, sparse in others and confusing all over the place, but compared to what had gone before this was a lean, modernist take on the baroque grotesquerie that D&D had quickly become. Oh, and it only went to third level for PCs. To go further with the game, the reader was directed to the then-forthcoming Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules set that Gary Gygax had been working on and was to emerge, with the Players Handbook, the following year. AD&D pulled down the tower that Holmes had built. In Holmes' game, rolled attributes counted for very little. Your prime requisite (e.g. Intelligence for Magic-Users) boosted your earned XP. Dexterity awarded you +1 or -1 to hit with missiles. Constitution earned you +1, 2 or 3 Hit Points. That's it. No Strength Bonuses. No extra spells for Clerics. No Armour Class modifiers. Oh, and all the weapons dealt 1d6 damage, whether they were a dagger or a two-handed sword. The effect of this was to de-emphasise combat as the central pillar of What D&D Is All About, in favour of exploration, traps, riddles, puzzles and NPC encounters. PCs are individuated, not by their attributes, but by the player's imagination. Since a Strength 17 Fighting Man functioned no differently from a Strength 7 Fighting Man, the colour had to come from characterisation. Holmes offers the standard D&D classes (including Thieves and Dwarves, Elves and Halflings functioning as classes too) but offers encouragement to go beyond this, citing his famous example of a diverse party of adventurers: Thus, an expedition might include, in addition to the four basic classes and races (human, elven, dwarven, hobbitish), a centaur, a lawful werebear, and a Japanese Samurai fighting man In a 1981 article in Dragon Magazine, Holmes is quite explicit about his free-wheeling approach to character generation: Most game systems rather rigidly specify what kinds of characters players may assume, but the majority of referees are lenient. If a player particularly wants to be an unusual or inhuman character, many referees will let him. It's not unusual to encounter player characters that are werewolves, Vulcans, samurai, centaurs or whatever. Fantasy role playing is, after all, an exercise in imagination In another Dragon article, Holmes confesses his own preferences for non-canon characters: For several years there was a dragon player character in my own game. At first level he could puff a little fire and do one die of damage. He could, of course, fly, even at first level. He was one of the most unpopular characters in the game, but this was because of the way he was played, not because he was a dragon. I enjoyed having dragons, centaurs, samurai and witch doctors in the game. My own most successful player character was a Dreenoi, an insectoid creature borrowed from McEwan’s Starguard. He reached fourth level (as high as any of my personal characters ever got), made an unfortunate decision, and was turned into a pool of green slime. Uh-oh. Dreenoi. Roll for initiative. Gary Gygax dismantled this approach with AD&D. Character attributes were exalted and character classes nailed down to very specific collections of powers and advancements. Whereas Holmes might identify his character as a 'Lawful Werebear', AD&D invited you to become a a 4th/5th level Half-Elven Cleric/Thief with a 17 Dex and a 16 Wisdom.

Perhaps that's the fascination with Holmes' work: it offers a brief window into a year (1977) when D&D could have gone another way. If AD&D was prog rock, with complexity and grand pretensions, then Holmes was that other flower of 1977: punk rock, with its three-chord simplicity and vigorous DIY ethos. Eric Holmes. Johnny Rotten. Rarely mistaken for one another. Two figures bestride the Internet, bearing the Holmsian lamp aloft. Zach Howard runs a fantastic Holmes blog and website, the Zenopus Archives, making the case in fair weather and foul for continuing to play D&D the way Holmes envisaged. He has done fantastic advocacy for the 'Tower of Zenopus' dungeon and delved into Holmes' manuscripts to explore how much Gygax diluted and redirected Holmes' intentions. Click the image to explore the underworld of Holmes Basic. The other is Michael Thomas, over at Dreamscape Design, who has published two loving Holmesian D&D retroclones: Blueholme (in two versions) and Blue Hack. Blueholme Prentice is pay-nothing on drivethrurpg; Blueholme Journeymanne is quite cheap on drivethrurpg or there's a nice hardback from Lulu; Blue Hack costs next-to-nothing on drivethrurpg The 2013 Blueholme Prentice rules (62pp) is a fairly standard OSR retroclone. Thomas takes Holmes' rules set and presents it in his own words, with the orderliness we now expect in good games design. There's a bit of advice on how to play the game and how to referee it. There's nice (public domain) B&W art. The ambiguities (e.g. elven fighter/magic-users) are cleared up. The attributes still offer almost no distinctions. Weapons all deal 1d6 damage. This is vintage Holmes, straight from the cellars. Carrion Crawlers get a copyright-dodging name change but I think Johnny Rotten and other veterans of 1977 will feel right at home here. Is there a use for this sort of game, besides nostalgia? After all, Charlie Mason's White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game one-ups Blueholme by going back to the original D&D rules set, but compressing character progression into 10 levels and adding variable weapon damage (well.... 1d6-1, 1d6 or 1d6+1 but it's variable!). It only slightly expands the modifiers for high/low attributes, it's got a low price point and it's rather more lovely in its typeface and old school William McAusland art. The appeal of Blueholme Prentice is precisely its strict boundaries. It offers a D&D experience with just three levels of experience. The King of the Realm, he's a third level Fighter. His Court Magician? He's a third level Magic-User. The Guildmaster Thief? Third level too! This is a world with a ceiling on it and, rather like crafting a haiku, composing scenarios within such limits draws forth surprising creativity.

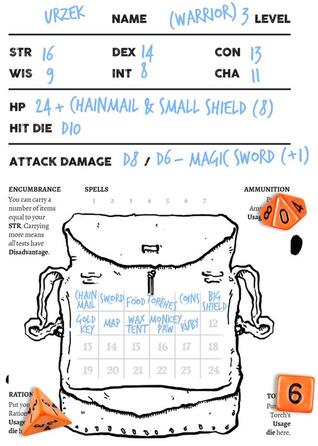

If you're not psyched by a 3rd-level-campaign, fear not! In 2017, along came Blueholme Journeymanne (118pp) on the back of a successful Kickstarter, with hardback rules and lots of original art by old school veterans like Russ 'Firetop Mountain' Nicholson that has a great late-Seventies vibe. Russ Nicholson's homage to David C Sutherland III's art panel that introduced the original Holmes Basic Set makes me feel happy in ways only the Germans have words for. All of this and twenty (count them, TWENTY) character levels, spells up to 7th level, hirelings and strongholds and VARIABLE WEAPON DAMAGE. Yes, at last. But not just different dice for different weapons. Oh no. All weapons still roll d6s (take THAT, Gygax) but puny daggers roll two dice and pick the worst while heavy weapons roll 2 or 3 dice and pick the best. Delightful! In just over a hundred pages, Blueholme Journeymanne muscles up alongside White Box and thoroughly intimidates it. Actually, they're both great games. It really boils down to whether you want your D&D campaign concertina-ed into ten levels or twenty. White Box has a cool fey-themed thing going on with its monsters but Blueholme Journeymanne is more Sci-Fi, with Lovecraftian Mi-Go and Deep Ones in the mix alongside Dreenoi. Yes, Dreenoi. Human, Dwarf and Dreenoi, together at last. Watch out for that Green Slime! This is where Journeymanne plays its Holmsian trump card. Character races are gone: poof! Instead, this: It's been a long journey, but we finally got there. You can play that Lawful Werebear at last. I like to think John Eric Holmes (who sadly died in 2010 and missed this renaissance in RPGs) is smiling upon this, up there, in the Outer Planes of Chaotic Neutral. Journeymanne gets the next-best endorsement from his son, Chris Holmes: These cyclopean corridors of peril await you and your players as they did my friends and me in 1976 when we explored the dungeons of John Eric Holmes. If this doesn't bring a tear to your eye, then you ought to be reading reviews of Miles Davis jazz albums. The Hacks I like, all on drivethrurpg (click on images for links) Blue Hack is a different beast. It's a variation on David Black's The Black Hack (2016), which offered an alternative streamlined take on D&D, with attribute tests replacing skills and abilities, ten character levels, super simplified classes, monsters and spells and groovy Usage Dice replacing tallying arrows, torches and rations. It spawned a host of imitators with various degrees of professionalism. Karl Stjernberg's Rad Hack is a fantastic pop art take on Gamma World, while Matthew Skail's Blood Hack is a cheerfully amateur (but very imaginative) interpretation of Vampire: The Masquade.

All well and good, but how do you Holmesify The Black Hack, which is about as stripped-back as an old school fantasy RPG can get? How is Blue Hack any different from The Black Hack? The answer, oddly, is to make it more like the sort of D&D that Black Hack is trying to escape from. The Black Hack enjoyed a recent Kickstarter and there's a fancy Second Edition out there but the original rules are a trim 20 pages that are a master class in clarity and elegant graphic design. The 'Big Six' stats here here (STR DEX CON INT WIS CHA) and four classes (Warrior, Cleric, Conjuror and Thief). Going up a level boosts your Hit Dice and lets you improve your Stats. Spells are summed up in no more than a dozen words each. This is the spell description for Power Word Kill: A Nearby target with 50HP or fewer dies and cannot be resurrected. Blue Hack takes all this and stirs back in some recognisable D&D. Dwarves, Elves and Halflings re-appear as character races, adding familiar flavour abilities, and Fighter-Mages are added to the class roster to accommodate those mystical elves. The presentation is a bit more expansive (it runs to 26 pages) and illustrated by the ubiquitous William McAusland's adorable B&W art, but the descriptions retain that charming "figure-it-out-yourself" brevity. Here's the explanation for the spell Limited Wish: Change reality in a limited way or time. When I think of the ink that's been spilled in D&D rulebooks and magazines trying to codify, limit, clarify and define what a 'wish' spell can do, this makes me want to break down and cry. Like a lot of Hack RPGs, Blue Hack feels like a slap in the face. Why did you just spend all that time and effort mastering Blueholme Journeymanne (never mind freakin' Dungeon Crawl Classics or D&D 5th ed.) if you could play fantasy RPGs as simply as this? Like a stage magician's prestige, it makes you blink your eyes and look for the trick. Can it really work like that? Well it can and it probably should, but something is lost. Perhaps what's lost is Holmes himself, whose genial ghost presides over every page of Blueholme in both its iterations but seems absent from Blue Hack, which is really just a pretty version of any already pretty game, given a more recognizably D&Dish spin. No rules for Dreenoi PCs. No Lawful Werebears. Maybe that's my beef with it. Skip to the end. My feeling is that, while the Hack RPGs are a fantastic development in roleplaying rules, they're not necessarily the way I want to go with old-school dungeonbashing. Sometimes, the flavour is in the rules themselves and, with minimal rules, you often get minimal flavour. With, say, the Rad Hack, the flavour is in the whacky radioactive post-holocaust setting. But with D&D-hacks, the flavour is in the D&D, which is exactly what you're taking out. Blueholme does a stunning job at honouring Holmes' legacy and provides a set of OSR rules that should be right up there for anyone wanting to explore the wild frontier of '70s-style D&D. Blue Hack is a solid Hack version of D&D, but I guess I don't really have a need for such a thing when the more conventional OSR D&D retroclones are already so sweet, simple and inspirational. There's a module for Blueholme - The Necropolis of Nuromen - which I'll review later this week.

Remember Vampire: the Masquerade? Mark Rein-Hagen's broody vamp RPG crashed into the hobby in 1991 and changed everything. It established White Wolf as a major gaming industry name and their Storyteller System as an influential rules set. It opened the World of Darkness as a compelling modern day setting, with contemporary heroes exploring a 'Gothic Punk' version of the world we know, one where supernatural evils manipulate humanity from the shadows. Perhaps most importantly, it offered a radical approach to roleplaying, with anguished characters possessing vivid inner lives, a focus on themes over action and a sort of bruised romanticism that hooked players at once. In Vampire, you play the monster, but you are horrified by what you have become and what you might turn into. I was drawn in by V:tM's coffee-table chic. So minimalist. So teasing. The 1st edition cover gave nothing away beyond "A Storytelling Game of Personal Horror" Vampire presented us a world familiar from much-loved '80s media - the American heartlands of Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, the world of Ferris Bueller, The Breakfast Club, the music of John Cougar Mellancamp and Bob Seger, the Blues Brothers, Halloween. Then it flipped it, focusing on the decaying industrial 'Rust Belt' and the hollowed-out cities. The mythology of feuding clans and warring sects, the historical revisionism that placed undead puppet-masters behind civilisation's great events, the concept of a 'Masquerade' that exposed the wholesome suburbia of a John Hughes movie to be a cynical lie... That's a heady cocktail. Vampire and its successor-games (werewolves, mages, wraiths and changelings) pretty much defined '90s roleplaying. Gone were the gritty, matrix-dominated high fantasy worlds of the '80s - take that, Rolemaster! - and in came improvisation, drama, roll-the-dice-then-make-something-up. Light candles! Play a Dead Can Dance CD! Wear a funny hat! Vampire didn't birth LARPing but it gave it focus and White Wolf threw itself behind the LARP trend with its 'Minds Eye Theater' line. LARPers. Crikey! I loved Vampire as much as anyone. It probably sustained my post-university interest in roleplaying which would have faded away otherwise, under the squeeze from career and family and ennui with dungeons and, I suppose, dragons. The great thing about Vampire was that the scenarios wrote themselves. Session One, you awaken as a vampire and you have to go and find food. From this premise, everything else flows and the tragedies, misadventures and dilemmas of that first night on the prowl set everything else in motion. You have to hide a body. You've offended another vampire. You've been discovered by your boyfriend. You've been introduced to the vampiric Prince and he wants you to do a little job for him. It wasn't perfect though. The Great Handfuls Of Dice (GHOD) offered a cluttered and blunt mechanic that didn't allow meaningful assessment of risk. No matter how many editions the game went through, they couldn't fix overpowered Celerity or underpowered guns. Roll all these and tell me if you hit... New Clans and Bloodlines were twinky and power-creeping and, from a 21st century perspective, insensitive in the representation of race and culture (so... Gypsies vampires are all thieves and the only two black factions are devoted to murder and demonism?). The representation of Middle Eastern vampires as a clan of fanatical assassins... problematic! And of course, that intoxicating lore which was such a springboard for the imagination back in '91 got codified, nailed down, explicated and quantified. It became a straightjacket, with its canonical timelines and dominating conflicts. Although a supplement exploring the anti-human Sabbat sect was extremely imaginative, it took the Jungian 'Shadow' of Vampire and gave it a face and the night lost its mystery as a result. There's a new version of Vampire: the Masquerade out - 2018's 'fifth edition' - and it's supposed to be very good. It takes a root-and-branch approach, restructuring the (terrible) dice system and Year Zero-ing the convoluted mythology. It can't overcome the game's '90s legacy, it seems, and has encoded characters with neo-Nazi iconography. Edge-lordery or Ass-holery? I can't comment. I've not read it. The reason I'm not wading back into Vampire: the Masquerade is that I've discovered The Blood Hack. I can buy the new 5th edition for £18 as a PDF - which is good value for a slick product - or The Blood Hack for £3 from drivethrurpg Author Matthew Skail describes The Blood Hack as "a love letter to dark games of the 90's that allow you to play the monster!" So we know what he's talking about, right? A bit of context. There are a lot of ...Hack RPGs out there, but the progenitor is David Black's The Black Hack (2013). The Black Hack is a super-streamlined retroclone of original D&D that takes a lot of liberties in order to capture the essence of Old School dungeon-bashing. It replaces all the tables and matrices with a simple mechanic: roll a d20 and get equal to or less than your relevant attribute (STR, DEX, etc). Players do all the rolling so you test STR to attack a monster and STR again to avoid being damaged by its attack. Saving throws are tests of CON or DEX or whatever. You might have penalties (actually, plusses, since you're trying to roll low) but the usual mechanic is to roll with either Advantage (roll twice, keep the lowest) or Disadvantage (roll twice, keep the highest). Black's innovation is the Usage Die. If your character has a crossbow it might have a d6 Usage Die. Every time you fire it you roll your d6 and if you roll 1-2 your Usage Die shrinks down to a d4. If you roll 1-2 again, your Usage Die is gone. You're out of ammo. Black applies the Usage Die concept to things like ammo, supplies, rations and torches, to avoid the fiddliness of keeping track of individual arrows or oil flasks. However, imitators have gone much further with this design. A Black Hack character, with Usage Dice Because Black is writing under the Open Gaming Licence, he offers up his game as a 'Hack' and a living document, inviting corrections and additions. Before long, there is a Space Hack, a Zombie Hack and a Cthulhu Hack and many other adaptations of popular RPG properties into this streamlined OSR rules set. Enter Matthew Skail, who takes up Black's distinctive approach and creates a sort of OSR Vampire game: Vampire but with levels and Hit Dice and the familiar six attributes of D&D, with the vampiric bloodlines as character classes. Obviously, intellectual property means that Skail cannot poach the Tremere and Gangrel, but his Anunnaki are sorcerers and Enkidu are shapeshifters, the Dracul are lordly warriors and the Lillim seductive manipulators: if you know V:tM, you can join the dots. Usage Dice do a lot more work in Skail's game. You have a Blood Usage Die and whenever you use it (to power abilities or go without feeding) you roll it and on a 1-2 it shrinks. Characters start off with a d4 Blood Usage Die, so there's a 50% chance any vampy exertion will leave you bloodless and hungry. Top vampires have a d10 Blood Die and you can do a lot with that: it will shrink to a d8 then a d6 then a d4 before you end up bloodless. Have fun! Feeding on a victim lets you take a step of their Blood Die (reducing a human from d4 to nothing) and add it to yours (boosting you from nothing to a d4). You can gorge yourself, taking your Blood Die to a step higher than your level-limit (ie. a d6 for first level characters). Feed on someone without a Blood Die and they die. Morality is also a Usage Die, but this is a die that gets bigger when it rolls 1-2. You start of with a d6 Morality (basic human, nothing special) and when you drain someone dry you roll it and on a 1-2 it increases to a d8. Now you're coldly inhuman in many ways; you're tougher in combat but you need to feed every night and sunlight deals Killing Damage. Vampires with a d10 Morality are nasty, d12 are monsters and d20 are doomed to become NPC horrors. With each step up, you get more vicious in combat but more vulnerable to sunlight, silver and holiness. Skail's vampires don't have reflections (I remember the brilliant 1998 TV series Ultraviolet and perhaps Skail does too because he's alert to the implication that vampires do not show up on film and their voices don't carry over telephones or the Internet). This show rocked and, yes, that's Idris Elba Skail also reinstates silver as a source of Killing Damage for vampires and downplays the idea that they're controlling the world: he presents his clans as engaged in little turf wars rather than directing massive corporations, but of course you can take the game in any direction you like.

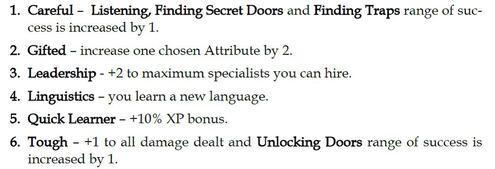

There's a comprehensive set of Blood Gifts and you get more by going up levels. Some of these Gifts are permanent powers (you can climb walls!), some require victims to have no more Hit Dice than you (the commanding Voice) and others require a stat test and a Blood Usage die roll. Super-strength 'Might' is another Usage Die that exhausts as you use it and refreshes the next evening. There are Blood Rituals you can use as an Anunnaki or buy into through the Mysticism Blood Gift and these let you create Renfield-esque Thralls, protect your Lair, recreate your reflection and other cools tricks. All of this is packed in to 54 pages with big typeface, lots of white space and some B&W art that's amateur but effective. It's not a perfect document. If you hate typos, then sedate yourself, because Matthew Skail has autocorrect turned 'off'. The ordering of material is haphazard and would be baffling in a larger or more complex rules set. Some material has been ported in from other hacks in a rather undigested way: we get lists of firearms and vehicles and their stats and prices as if this was a set of skirmish rules. but only perfunctory rules on humans, Thralls and vampire politics. The assumption is that you're fighting other supernatural mooks in the night. But of course, you can make use of the game in any way you like. I've found The Blood Hack to be a fantastic gateway back into vampire-themed roleplaying with a OSR aesthetic. It lets me ditch the baggage of the World of Darkness and construct my own setting with vamps who are rather more mystical and varied than the White Wolf varieties. I've started a campaign - Nights of Fire, set in London in 1940 on the eve of the Blitz - and of course that's going to end up hacking the Hack, with my own rules and variants, new clans, new powers, all of that stuff. The Blood Hack doesn't have Malkavians! That so needs to be fixed... No sooner have I finished praising Szymon Piecha's excellent White Box supplement Expanded Lore (for its new character classes and campaign rules) than it gets a fresh coat of paint and reappears in drivethrurpg as version 2. Click the image to visit drivethrurpg. The book is pay-what-you-want Most of the text is unchanged (including no saving throw for the Druidic Sunburst spell!) but a couple of classes have had major rebalancing and there's a brand new class - the Witcher, sorry, no, the Hunter. Monks The original D&D Monk class was incoherent and unbalanced, but had memorable and popular abilities. Szymon revised the Monk for Expanded Lore v1, creating a much more subdued martial artist. Too subdued really. The new Monk had impressive attacks (two of them!) and healing at 1st level but rubbish AC and - and this was the problem - no where to go. Leveling up didn't improve open hand combat and the Feats were minor affairs. Szymon fixes this by giving the Monk a 1-6 scaled Martial Arts skill, similar to a Thief's Thievery skill in White Box. This number (starting at '2') is added to the Monk's AC and saving throws to dodge missiles. It is also the amount of HP healed by the Monk's hour-long daily Meditation. Now we have a Monk that gets significantly better at things, with base AC starting at 7 [12] and improving to 3 [16] at 9th level. My homebrew goes a bit further. I think Martial Arts should be added to the Monk's base move, producing 12 at 1st level rising to 18 by 9th. I notice the Monk's To Hit Bonuses have been hiked slightly too, giving them +1 To Hit at 2nd level, like Fighters. The Feats are a more robust bunch of powers, such as walking on water and a further small hike to dodges and AC. The big news is Nirvana, which lets you heal 1d6 after winning in battle, and Vital Strike, which lets you paralyse an opponent. Vital Strike is hemmed with limitations: it has to be your first attack against an opponent, you have to hit and deal damage and the opponent has to fail a saving throw. Iron Knuckles grants +1 damage in open-hand combat but crucially lets your hands count as magical weapons: a much-needed buff. I could quibble about Vital Strike being so powerful but so limited; I prefer powers to be weaker but sure-things. Maybe no saving throw but the paralysis only lasts one round? But be that as it may, Szymon's revisions effectively abolish my Monk homebrew. Paladins The original D&D Paladin was another over-powered creation that overshadowed Clerics. Szymon's Paladin redressed that, moving these righteous warriors away from Cleric-territory but keeping them Cleric-adjacent. They were perhaps a bit boring though? The new Paladin is even further from its original template but has much more attractive powers. As with the Monk, Szymon gives Paladins a signature trait, in this case Pride. However, this trait starts at 2 at 1st level but scales up to 20 by 10th level. Moreover, it's not a skill so much as a pool of points. Pride is spent to do the Paladin's healing and smiting, so a 1st level Paladin could heal 2HP or smite an enemy for an extra 2 damage, or heal 1HP and deal +1 damage. Pride is replenished by a single day of rest and gets halved if the Paladin breaks his vows. I've got very mixed feelings about this. Giving a character a pool of points to fuel abilities has never been the D&D way. It would make some sort of sense to give Monks 'chi points' but giving Paladins 'Pride points'? Just what do these points represent? Then there's the clash between this system and the 1-6 scale that applies to Thieves (and Szymon's Bards and now Monks too). And all this innovation just to scale an ability that could have been set at '2HP per level' with pretty much the same results! It's not as if Pride fuels any other Paladin activities. The Paladin's boring Mount is unchanged, but the Feats get a makeover. The old Blessing and Inquisition get merged: now Blessing lets a Paladin cast bless and detect chaos each once a day. Inspiring Leader and Inspiring Protector are both terrific party buffs: nominate an ally to receive +1 To Hit/damage or +2 AC for that round - and you do this at the start of the round so it's not even an action. This moves Paladins into the territory occupied by Bards in other iterations of D&D. Witch-Hunter offers an amazing half damage from magic attacks plus the ability to identify any spell cast on you. This moves the Paladin far away from its quasi-clerical template. It's now much more like the Cavalier that appeared in Unearthed Arcana (1985). Has it moved too far away? Shouldn't Paladins get a Feat that lets them turn undead as a 1st level Cleric? If we're going to have pesky Pride points (and the name itself skews Paladins away from the Christian archetype) then shouldn't they fuel other things? I'm not convinced by this version of the Paladin, though it is much more balanced and very distinctive. Bards Szymon did a good job reconceptualising Bards, taking them away from their original 'jack-of-all-trades' remit without turning them into the super-spell-casters and party-buffers they became in later editions. The Feats were a little underwhelming, so Szymon revisits them. But before we look at that, there's one feature of Szymon's Bards that hasn't changed and that I strongly oppose. Szymon's Bardic Charm doesn't work on undead or demons. Unintelligent undead - fine! But if PC Bards are to imitate the greatest Bard of them all, they should be able to descend into the Underworld and use the power of music to charm the damned souls there and the demonic Furies that guard them. Undead and Demons are touched by art too! The Bard's Light Step feat still makes traps trigger only on a 1 in 6 chance (amazing power) but now confers +1 to AC too. Simple Counter-Spells now confer +3 rather than +2 to saving throws vs Spells. Swashbuckler used to confer +1 To Hit with light blades, but the new Fencer lets you choose between +2 To Hit or +2 to AC, which is powerful and flexible. A fine set of revisions, slightly pumping Bards as a combat class, but not too much. This is all good stuff. Fighters Szymon offered Fighters a range of 'sub-classes' which distinguishes them from each other at 1st level. Berserkers and Anti-Mages haven't changed. Archers now deal +2 damage rather than a bonus d4. I'm in favour of giving players fixed amounts rather than imposing more dice rolls for such trivial variations. Cavaliers and their mounted bonuses have gone, but now there are Mercenaries that re-roll critical fails with two-handed weapons. It's a neat ability but I can't see what it has to do with being a Mercenary. Nobles have been renamed Guardians, which makes their damage-redirection less setting-specific. Soldiers no longer get a shield bonus but they do get the ability to assign a +1 To Hit bonus to an ally at the start of each round, which I like. Swordsmen are restricted to leather armour but gain +1 To Hit and damage with swords and improve their AC by their Dexterity bonus. Wait, what? Yes, it seems Expanded Lore proposes abolishing the normal Dexterity adjustment to AC and I missed the memo. Well, I don't think I'll be incorporating that. Slayer has been removed - I think because it treads on the Hunter's toes. There are some sensible changes here, but nothing ground-breaking. If, like me, you still let Dex bonuses improve AC for everyone, then the Swordsman needs revising. I think giving him the Bardic Fencer ability to toggle a +2 bonus between To Hit and AC on a round-by-round basis would do it. As for Mercenaries, perhaps the party could 'buy' them a buff like +2 To Hit or +2 Damage for the duration of a combat in exchange for an extra 50gp/level to their share of the loot. The Hunter One of the surprise absences from the original Expanded Lore was the Ranger. Well, now he's here, but de-Tolkienified and blended with the Witcher to form a new class with some distinctive progressions. Hunters are like Dexterity-themed Fighters, limited to chain mail and slightly lower in Hit Points at 1st level. They progress in To Hit Bonuses in a similar fashion to Fighters and are only slightly worse with their saving throws. They have a Tracking Skill which operates on the same 1-6 scale as Thievery, Bardic Charm and Monkish Martial Arts. Hunters gain +2 to saving throws against wild animals such as Poison and (for some reason) Illusions. I wonder what wild animals create illusions? Perhaps this refers to fey woodland creatures like Dryads. Hunters collect trophies from their kills and once they have 20 trophies from a parrticular type of foe (e.g. 'demons', 'undead' or 'animals') they get the title 'Slayer of _____' and enjoy a +2 damage bonus against them. They can also choose to become an Expert in one of the foes they have the title Slayer for and they never need to roll to track these. As with Paladins, there's a mechanic at work here that operates at cross-purposes to the normal White Box systems. In this case, a type of progression that's not linked to leveling up. Don't get me wrong: I like it as a mechanic. But I wonder if other classes shouldn't be allowed something similar, with Magic-Users specialising in certain spells, Clerics against certain undead, etc. This would effectively abolish the Hunter as a distinct class, since all characters could become Slayers too. It would also move the game far beyond 'Original D&D' in structure. Like the scene in Predator (1987) where Arnie hides in the mud? Well Hunters have a feat called Ghost that makes them invisible if they lie still in thickets, water or mud and gives them +1 AC when they stand up. Tracker adds +1 to Tracking and Hunting Company (and I really like this one) confers +1 To Hit for the entire party against monsters the Hunter has successfully tracked. Quick Shot and Quick Stab both let the Hunter re-roll damage, but the second (rather than the higher) score has to be taken. Nonetheless, other players will be jealous of this. Life Reader lets the player know a monster's remaining HP - a nice 'meta' power but it depends how you play (I often tell players monster HPs to generate drama). Hunters are a well-designed class with intriguing powers to bring to the table. The only problem is that, compared to Rangers, they're a bit one-note. They're just really, really good at killing things. That's it. That's their jam. No using crystal balls or concocting herbal remedies, no minor spell-casting or passing without trace. There's nothing mystical about Hunters. Nonetheless, I might revisit my White Box Ranger and dial back some of its Hunter-like powers to focus on wilderness survival instead, so that the Hunter can corner the market on slaughter. Szymon Piecha is pretty experienced in rules design so these classes hang together nicely without overpowering the game. Well, perhaps the Hunter has a bit too much going for it. The main thing that Expanded Lore did - amd now does very explicitly - is move the game away from its OD&D roots into being a new OSR-style RPG entirely. These Bards, Monks and Paladins don't really resemble their D&D originals and the Hunter, while old-school in flavour, owes very little to the Ranger.