|

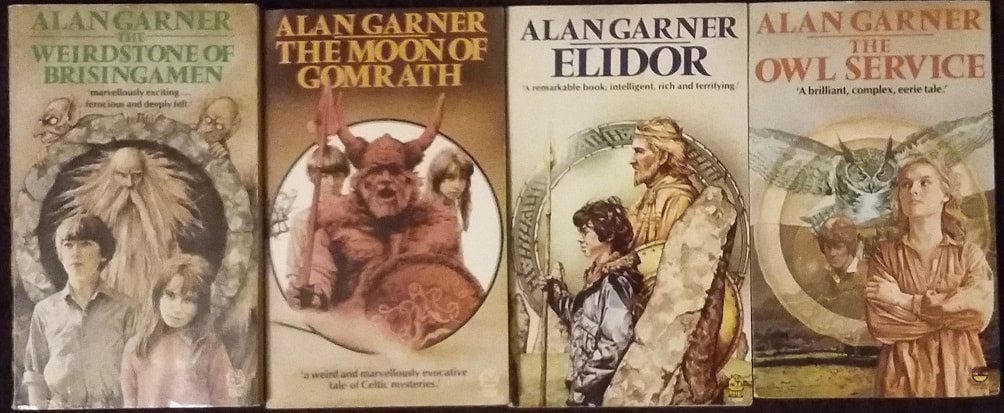

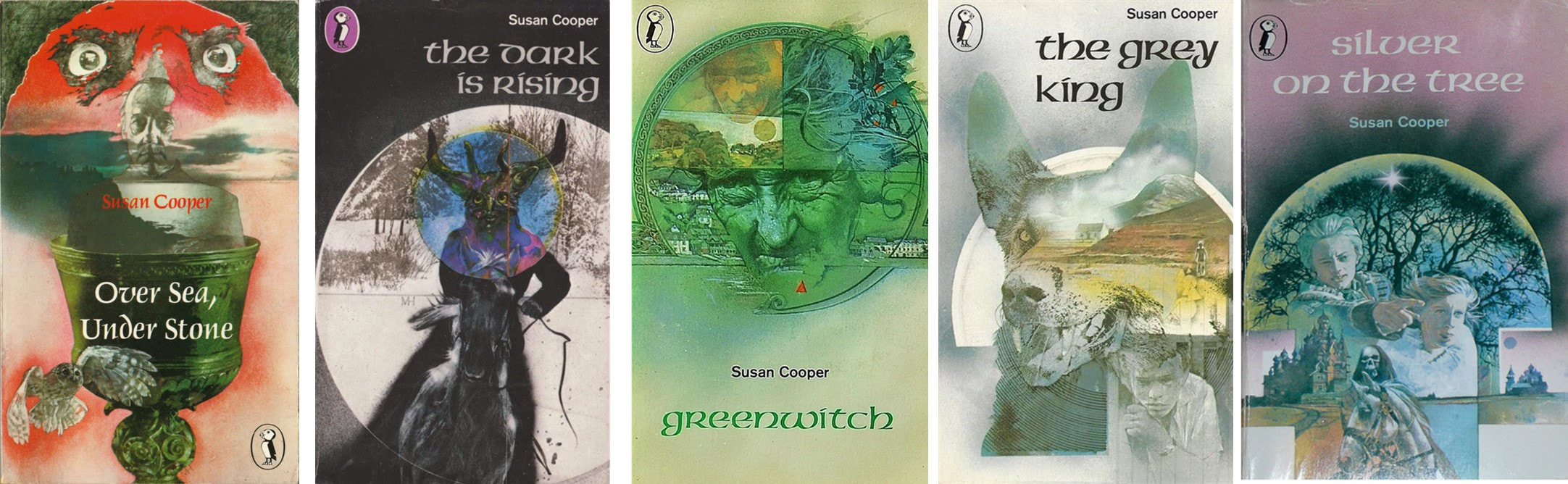

Consider a route you often walk, one you know well, going from home to work perhaps, or college, or to a friend's home. Doubtless, as you go along your familiar way, you pass a little lane or alley. It’s overgrown and clogged with weeds. It doesn’t seem to go anywhere. It just snakes between houses and disappears into leafy shadows. Probably it peters out among bin bags and barbed wire, or else ends with a ‘Private Property: Keep Out’ sign. You’ve have never abandoned your habitual journey to explore that lane. After all, why should you? But suppose you did! Suppose you went down that lane, leaving behind the noise of the traffic, the hum and clatter of modernity, and wrestled instead with the stinging nettles and the bobbing flies. Suppose you found grass under your feet and birdsong overhead. Imagine yourself recognising them by name: the old wren and whitethroat, the songthrush, the fierce yellowhammer. Imagine finding, at the end of that lane, overshadowed by the branches of hazel and sad yews, an upright stone, tilted, worn with age and furry with moss. And overhead, the song of the wren bubbles like a fountain from the treetops. Joy pierces your heart. Perhaps you stand a while, with your hand resting on that old stone. ‘I will come here again,’ you tell yourself, ‘when I’m not so busy, when I have more time.’ But you know that, search as you will, you shall never find this place a second time. Suppose, when you turn to go, you find you are not alone. Your companion is old, with a face as creased and crumbling as the stone from which he seems to have sprung. His coat is green as the creeping moss but his scarf is golden like the dappled sun and his eyes are merry as a wren’s song. “I’ve been waiting for you,” he says. Then, turning to step between the leaves and branches, he adds, “Follow me!” O, the child you used to be would not have hesitated. To step into the Hedgerow and out of this world, to follow the green man into strange centuries, no matter the peril: it is an adventure you have forgotten to yearn for. But if you have not abandoned yearning, well, I wrote this game for you. Step Into the HedgerowYou can follow any Hedgerow for miles, threading country lanes, crisscrossing fields and meadows. You can smell the foxglove and cow parsley and taste the blackberries and rosehips. Yes, but if only you could enter INTO the Hedgerow, what would you find inside? You would find a path, grass underfoot, bracken and thorns on either side, and a faint light from above, where the young leaves work their alchemy on sunlight – and ahead, drawing you on, the wren’s imperious summons. The path takes you through clearings and in each clearing there is a vision. A maiden weeps over a broken harp. Two crows feast on a dead knight. A statue points to a gravestone covered in vines and etched with runes: this too is in Arcadia. And overhead, the murderous cawing of the ravens gathers power. There is a Darkness in the Hedgerow that contends with the Light. The Hedgerow is really a Maze, you see: it is a Labyrinth connecting the centuries. Inside the Hedgerow you will meet other travellers who join your adventure: a scarecrow wearied with warding his acre, a soldier of fortune burdened with the immortality she never sought, a witch-girl bickering with a talking mouse, a cheerful troll with a turnip for a head. Some of Peter Johnston's stunning art for Through The Hedgerow When you leave the Hedgerow together, you have returned home but in a changed time. The invading Danes set flame to thatch while King Alfred hides in the marshes. Puritan mobs armed with muskets drag defiant women to the scaffold. A jilted fay stalks her paramour on a Victorian steam locomotive. A hag kidnaps children from the air raid shelters of wartime Britain. In all these centuries, the Dark is at work and the visions you witnessed within the Hedgerow will guide you in your mission to oppose it. To pass through the Hedgerow is to enter a war. It is a war that endures across the millennia, fought in every hayrick, under every stile, in the contested branches of every oak, in every sleeping byre. In this war the wren and the ouzel are your comrades against the basilisk and the vampyre and the witch-hunter with his cold iron chains. The shadows are lengthening. Time to take up arms. Inspirations for AdventureIf you’re my age, which is older than acorns but not yet an oak, you enjoyed a childhood of particular imaginative richness. There was Doctor Who of course: a source of primal terror and wild possibility as we peeped from behind sofas or barely parted fingers. We were too young to notice the shoddy sets. We just wanted time travel and monsters, but we got ecological fables and meditations on mortality into the bargain. Of course, the beloved face from Doctor Who returned in Worzel Gummidge, Jon Pertwee’s hero-fool now a scarecrow guarding a field in Sunnybrook Farm. Even in this lightweight fare, the enigmatic Crowman who makes all scarecrows hinted at a wider and more solemn legendarium. If you’re as far from an acorn as I am, the Crowman’s ancient eyes glinted with a faded memory: the actor Geoffrey Blaydon had played the time-slipped wizard Catweazle nearly a decade earlier. Who can forget Children of the Stones, a series which introduced us to a cold gnawing dread, so different from the visceral alarm of Doctor Who. The story made me (quite rightly, I believe) apprehensive about standing stones, thanks to the unearthly and atonal soundtrack by the Ambrosian Singers. A children's show with a theme tune to drive you quite mad Another show with a theme tune that sounded not of this world was The Tomorrow People: more troubling than Doctor Who, with its themes of puberty, repression, and magical outsiders hidden in plain sight in a society that feared them. It resonated with me far more than did the (similarly themed) X-Men, especially the idea of a group of friends utterly dependent on each other, but linked to a cosmic community of which ordinary humans could not guess. Come to think of it, it's the marriage of teasing monochrome imagery and that fantastic propulsive melody The love of rural folklore was mediated through repeats of Oliver Postgate’s strangely doleful Noggin The Nogg, later Ivor the Engine, and The Wombles. The Herb Garden, Parsley the Lion, and The Magic Roundabout established in my child's mind the important truth that there can be no more suitable place to meet with a godling or demi-demon than a walled garden. In the lands of the North, where the Black Rocks stand guard against the cold sea, in the dark night that is very long the Men of the Northlands sit by their great log fires and they tell a tale... And those tales they tell are the stories of a kind and wise king and his people; they are the Sagas of Noggin the Nog. When the age for reading novels arrived, there waiting for me was Stig of the Dump, Five Children And It, The Ghost of Thomas Kempe, and Watership Down. But these were only setting the stage. The Weirdstone of Brisingamen by Alan Garner subjects young Susan and Colin to a journey of nightmare and delight, hidden among the landmarks of Cheshire, where they must keep a mystical jewel out of the clutches of the Morrigan and her morthbrood conspiracy. Its apocalyptic sequel The Moon of Gomrath takes place on a numinous night: “one of the four nights of the year when Time and Forever mingle.” Frankly, it defies synopsis. Garner wrote other books and a case can be made for The Owl Service and Elidor. All have a sense of creeping menace, of ordinary relationships revealing pagan themes, of nightmares lurking in plain sight that only children can apprehend. Garner's books in turn were surpassed by Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising and the quintet it dominates: Will Stanton, seventh son of a seventh son, discovers he is the last of the Old Ones to be born on Earth. His arrival unleashes a cascade of prophecy as the Dark rises amid the familiar farmlands of Buckinghamshire Cooper weaves King Arthur into the story (in an oblique way), the Wild Hunt, primal goddesses of the sea, and a quest to retrieval talismans of ancient power. As with Garner, ancient pagan cycles recur in modern families and innocuous folklore and village ceremonies are revealed as totems of dignity and dread. The scene in Greenwitch where Will and Merry confront Tethys the Ocean still shivers me. “Even in the darkest sea they knew they were observed and escorted all the way, by subjects of Tethys invisible even to an Old One’s eye. News came to the Lady of the Sea long, long before anyone might approach. She had her own ways. Older than the land, older than the Old Ones, older than all men, she ruled her kingdom of waves as she had since the world began: alone, absolute.” Brr-rr. Building The GameI wanted Through The Hedgerow to allow for a type of roleplaying quite different from high fantasy adventure, like D&D, or supernatural investigation, like Call Of Cthulhu. For one thing, I wanted a game where you can roleplay children alongside adult characters – and for the children to have interesting contributions to make. This means de-centring combat and violence and allowing wits, charms, riddles, jokes, and pranks to accomplish the stuff that other games demand you resolve with a broadsword or a gun – but still to allow for characters with broadswords and guns to do their violent thing. Tales From The Loop offered me good ideas about a children-only RPG that still featured adult themes and elements of horror and peril. The One Ring does a good job drawing together characters of very different power levels – an immortal Elf or battle-ready Dunedan alongside a Hobbit. Through the Hedgerow's Check & Challenge system was half of my solution – I’m not going to call it an elegant solution, but I think it’s an innovative one. I’ll cover the mechanics in a future blog. The other half of the solution is in the structure of the adventures themselves. The Player Characters arrive in a historical period where they know the landscape and are concealed by the mystical Glamour, but struggle to interact with the mortal inhabitants. This is a problem because the riddle they receive at the start can only be interpreted with the help of mortal NPCs. Moreover, only by taking Oaths to mortal NPCs do characters get the power boost they need to confront their enemies. This means the game contains a lot of befriending, questioning, offering help, trying to fix the life-problems of ordinary people (or at least, people who are ordinary enough for their period – the life problems of a Viking chieftain can be pretty hair raising by modern standards). You might create a character who can wrestle trolls, but you might find yourself trying to reconcile a dejected husband and his angry wife. Of course, you’ll get to wrestle trolls too. This gives a Through The Hedgerow scenario a distinctive pattern. Receive your ‘conundrum’ (as the mission is called). Investigate the NPCs in the local community to work out who you can help and what they can teach you. Then identify your mission target and claim victory. Except of course, the Dark is sending its emissaries abroad to beat you to it. The clock is very much ticking and revealing your Otherworldly nature to hapless mortals only advances the timer and invites the Dark to intervene, probably harming innocents. You need to make use of all the resources to hand. This includes mortal NPCs of course, but also the supernatural community, up to and including the enigmatic Old Gods who still haunt the landscape. Magical Herbs can help you, fragments of Elder Lore can be discovered and traded, and the power of Mythic Sites can be unlocked with world-changing consequences.

I’ll devote a blog to each of these concepts in the coming weeks.

0 Comments

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed