|

The last blog outlined a plan to launch into Greg Gillespie's epic Barrowmaze megadungeon, but using the rules for '90s indie RPG Forge: Out of Chaos. Warning: Minor spoilers for Barrowmaze content ahead The Dungeon FodderForge character creation is a bit more involved than D&D, but not too much so. There are six Stats on 2d6 and each has a decimal value as well, rolled on a d10. Anything between 4.5 and 8.9 is in the 'normal, no modifier' range. My players excel at rolling really badly at Stats. Fortunately, skills and races will offset bad rolls slightly.

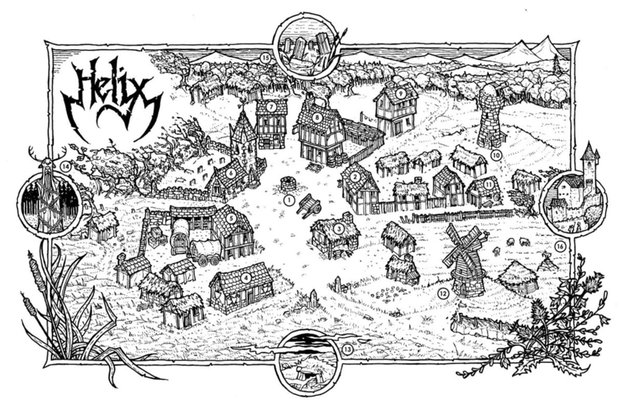

We wanted to avoid the 'psychotic gorilla' tropes about Ghantu, so Ng-Johnann is a landowner. He lives in a dilapidated mansion near Helix and owns the Stone Circle. In my twist on BM's setting, this site is sacred to Grom, the damned war god and creator of Ghantu and other monsterfolk. Grom's religion has been suppressed by the new Church of Enigwa in Helix and Ng-Johann has fallen on hard times. Adventuring might pay to repair his leaking roof (1000gp). By the way, the Ng-prefix is a Ghantu honorific, like 'Mister' or 'Sir.' I'm interested in whether the Ghantu cognitive deficit will play out like autism (a la Drax the Destroyer) rather than antisocial personality disorder. I want to emphasise the distrust and fear the Ghantu inspires in Helix, but also the respect from people who still venerate Grom or respect the strength he provides.

We decided to play Jher-em as Edwardian English gentlemen, like something from Wind in the Willows or Jeeves and Wooster, but with their distinctive phlegmy wheeze. "What-ho, cousin!" is their usual greeting, as well as "Tip-top, old chap!" and "Tally-ho!" The important NPC Ollis Blackfell has been recast as Jher-em as well as the mage Wiselaumas from Bertrand's Brigands. These conversations make for some merry interplay. I like to imagine that the Jher-em engage in banal pleasantries and conversation about the weather precisely because they are telepathic, so focusing on polite trivia is the best way of keeping other Jher-em out of your head!

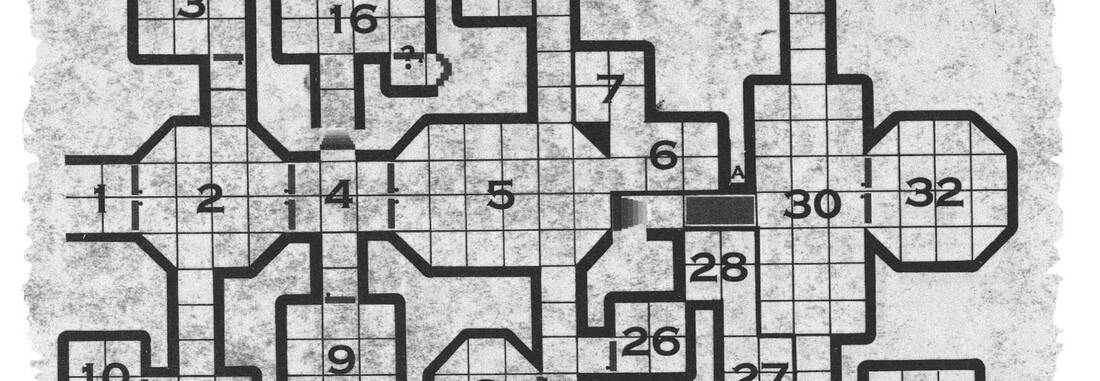

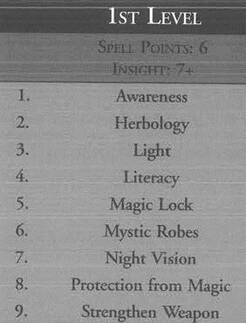

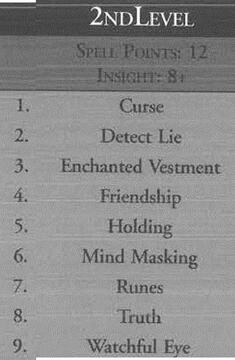

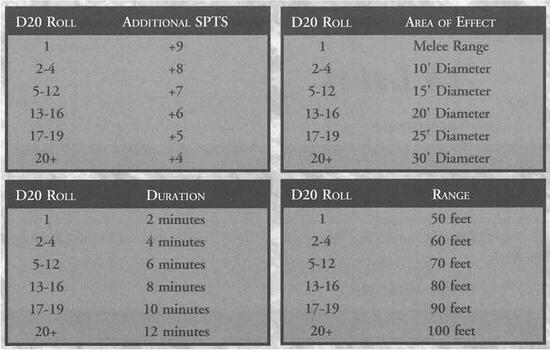

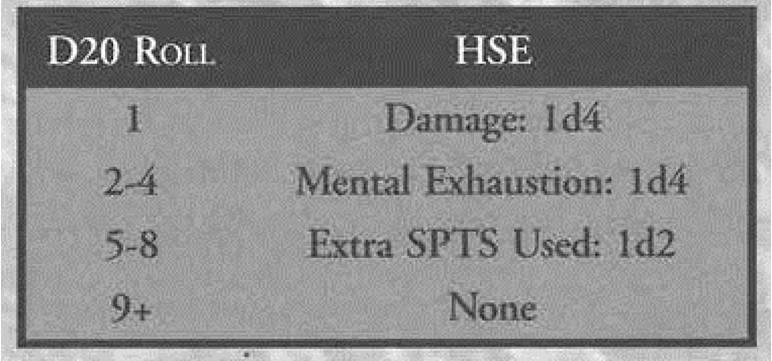

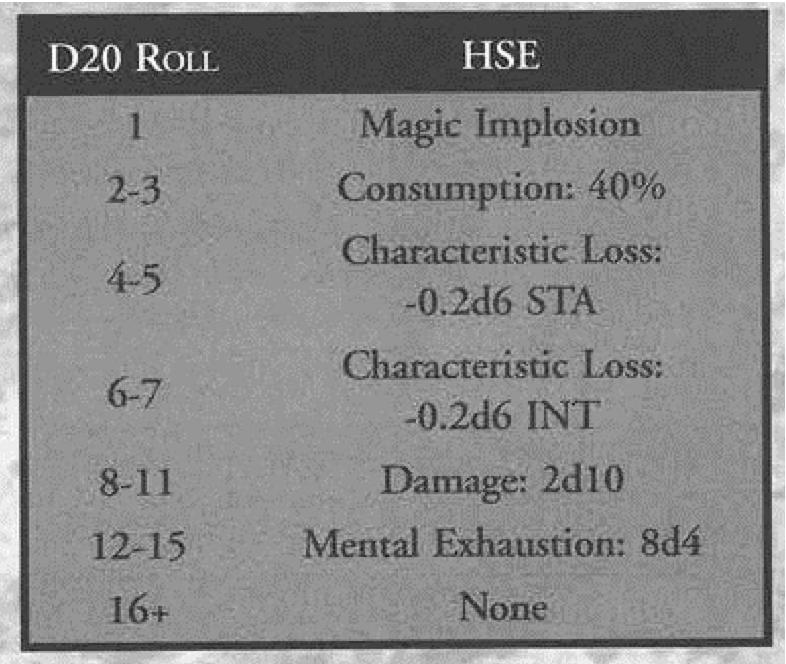

I'm playing Kithsara as immensely cultured and rather cerebral creatures, but Tshu'a is in conflict between the civilised behaviours he learned in servitude and the barbaric impulses from his upbringing in the swamp. He also has to keep his magical talents hidden from the Church of Enigwa. It's been a long time since they burned a wizard, but if they start up again with anyone, it'll be someone like Tshu'a. Session One - First Foray to Find a Fallen PrinceThe town crier announces that young Krothos Ironguard hasn't returned yet from a foray into Barrowmaze. Ollis Blackfell wants to downplay the seriousness of the situation since the young prince often takes off with his friends to hunt or debauch. Nevertheless, a reward of 250gp is offered for his quick and safe return. The only other adventuring party in town is Bertrand's Brigands and they're nursing wounds after a run-in with Renata's Robbers at the Old Bridge. Our heroes meet up at the Brazen Strumpet and decide to beat the rush by hiking out to the Barrowmoor first thing in the morning. After a bit of mound-mapping, the heroes find the Great Barrow, but icy mists close around them and out of the murk stumble two undead warriors. Tshu'a strikes down one, but it reassembles itself instantly wherepon the other seizes the panicking Ghantu by the throat. Yes, these are Coffer Corpses, ported across from the old AD&D Fiend Folio. Not only do they throttle and terrify, but they also need magic to kill, so they're just about the worst thing that the daylight wandering monster table could throw out. Tshu'a uses his Ice Bolt spell to free Johann, who abandons his two-handed sword and flees. A second Ice Bolt demolishes the first undead, but the second corpse advances and Tshu'a is out of spell points. Everyone flees into the Great Barrow: Johann falls down the pit and knocks himself out and the other two hide from the prowling undead before descending to help the Ghantu recover with binding kits and healing roots. This was an electrifying start: full of eerie menace, then horror and the threat of Total Party Kill. The heroes are left at the gateway to Barrowmaze without spell power and resources depleted. After this brush with death, the party become super-careful and cautious. They map corridors and get their bearings before trying other doors. They set off a trap, loot some alcoves and hide when more wandering monsters pass by. They venture quite deep into Barrowmaze and find a magic weapon - hallelujah! - and when some Zombies march up they run away - right into the maw of a Mevoshk. A Mevoshk is a Forge monster I substituted for a comparable enemy in the dungeon. Mevoshks are fast and their venom paralyses; you suffocate within ten minutes unless a Brye Leaf is applied to the wound. Odwood is bitten immediately and starts to succumb to the venom. Another TPK looms, but Tshu'a pulls out the Vigoshian Herb he bought in town. It gives a temporary boost of Spell Points, but a permanent drain on your Intellect Stat. Tshu'a uses the SPTS to fuel Ice Bolts and then Johann chops the thing's head off with his big sword. The fight was observed by a band of hideous Mongrelmen who rejoice in the Mevoshk's death. Though paralysed, Odwood communicates telepathically with them. They want to retrieve their jewels from the monster's hoard, but offer Brye Leafs to save Odwood's life and they hand over some nice (but not the best) gems in gratitude for slaying the monster before they scuttle off. Did I fudge this? Well, yes and no. There was a successful wandering monster check from the noise of the fight, but I selected Mongrelmen as the encounter. The idea that the Mevoshk had been preying on them had been foreshadowed by tracks the players had been puzzling over. The exchange of a Brye Leaf for a small fortune in jewels seems like a good deal for the NPCs. No jury of my peers would convict me! The players decide to beat a retreat, but the Zombies are still blocking the way out. Tshu'a decides to burn those remaining SPTS on his Big Second Level Spell: Spark Shower. And boy, does that make a difference or what! The Zombies frazzle and the players escape ... but alas, no sign of Krothos Ironguard. Evaluating BarrowmazeEveryone was thrilled with this old school dungeon crawl and his keen to return! The Barrowmaze itself is intensely atmospheric: silent, dripping, cold, eerie. There's a tempo to things, with very frequent wandering monster checks and extra ones occasioned by any sort of noise. The players are pondering how opening doors can be made, if not quieter, then at least quicker. The dread of making noise grew as the evening advanced. So did the dread of staying too long in Barrowmaze and being caught on the Moors after sunset. After all, if you can meet Coffer Corpses in broad daylight, what abominations will you run into by night?!? Helix will take longer to make an impression, but some features established themselves as distinctive: the town crier, the expectation that adventuring parties will descend on the village as the Spring arrives, Ollis Blackfell as a sinister vizier, Bertrand's Brigands as (friendly, for now) rivals. The Forge setting manifested itself as the Church of Enigwa spying on people for signs of magic use. Evaluating ForgeThe players were delighted with the energy Forge brought to the tired tropes of dungeoncrawling. Forge has an action economy rather different from D&D/Labyrinth Lord. PCs are tougher, more resilient and more capable that 1st level D&D characters. There are resources to track and decisions to make about their use: do you apply binding kits to wounds? when is a good time to stop and repair armour? should you push your luck by using enhancing herbs? should you conserve your SPTS or burn them in a dramatic burst of eldritch power? In terms of character development, Forge doesn't have XP. Your main advancement is through getting money to improve armour and equipment, better herbs, more binding kits; mages need spell components or back-ups in case they risk 'pumping' their spells and it goes a bit wrong. Nonetheless, we realised that skill advancement is going to be painfully slow at this rate. This led to ongoing house rule tweaks. There's nothing wrong with Forge's slow advancement, but the characters do need to keep pace with D&D characters if they are not to be overwhelmed deeper into the dungeon. Essentially, beginning Forge characters function like 2nd level D&D characters in terms of resilience and combat odds - but they gain much less as they advance and advancement is slow. A Forge PC with Magic at level 2 is maybe equivalent to a 3rd or 4th level MU in D&D. A warrior with Long Sword 3 hasn't significantly advanced from their starting build, whereas in D&D a 3rd level Fighter is markedly better. What's interesting about this for me is that, where Forge gets noticed at all, reviewers like to condemn it as a D&D pastiche that brings nothing new to the dungeoncrawling experience (for example, here on BGG). Our experience so far is that this isn't true. Forge's little innovations add up to a gaming experience that feels very different from D&D. We'll iron out the creases as we go. But for now, we're delighted with the drama, mysteries and sense of dank, chill menace that Barrowmaze exudes and Forge is measuring up very well as an alternative rules set to old school D&D.

0 Comments

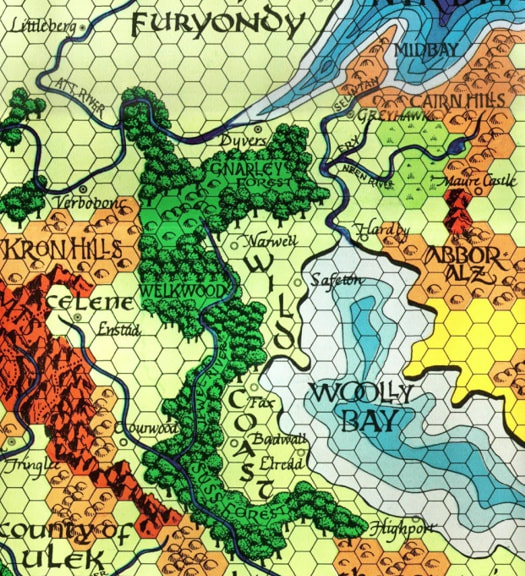

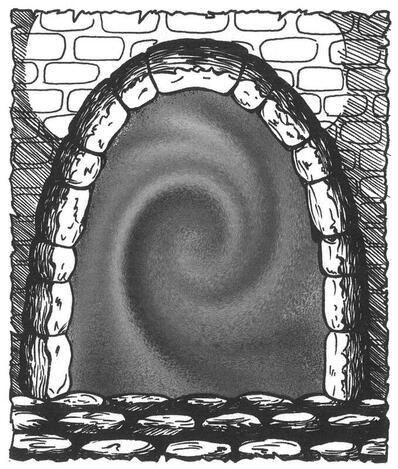

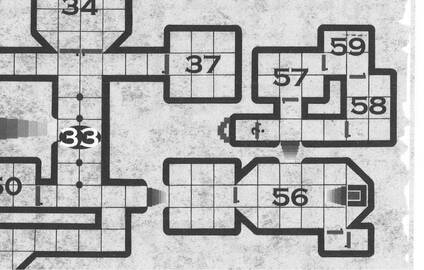

A challenge has been laid down! We're going to delve into Barrowmaze. But we're not using AD&D or Labyrinth Lord or even sleek little White Box FMAG, oh no. No, we're going to use our beloved fantasy heartbreaker Forge: Out of Chaos (see blogs passim, or here). Very minor spoilers ahead for the village setting in the Barrowmaze adventure. Wait - what? Barrowmaze?Barrowmaze is a megadungeon, published in 2011 by Greg Gillespie, who has built a career out of designing, publishing and running college courses on these vast dungeons. With over 600 detailed rooms, the Barrowmaze dungeon is designed to be the sort of thing you walk into as 1st level noobs and walk (or crawl) out of again, months or even years later, as high level heroes. It's an entire campaign in one dungeon complex, plus its equally well detailed environs. Modern cover and charming old school monochrome cover. The links are to Labyrinth Lord (OSR) editions but there are 5th ed D&D versions as well. Barrowmaze has an interesting structure, because it doesn't descend deeper into the earth through levels of increasing toughness, hostility and reward. Instead, the vast underground complex sits below a surface level Barrowmoor where the landscape is dotted with 70 barrow mounds. Each of these is a stand-alone mini or micro dungeon and a half dozen of them are access points for the Barrowmaze below. As you travel further into the Moor, the barrows get nastier and more lucrative to raid and the Maze below features more awesome monsters and treasures. In theory it's possible for lucky and reckless novice adventurers to proceed directly to the further extent of the Moor and discover an access point to the most perilous part of the Maze, where the Big Bad Evil Guy(s) are waiting. But we won't be doing that now, will we guys. Guys? So, seriously ... Forge?If you've followed this blog, you'll have come across my advocacy of this late-'90s indie RPG before. It's part of a stable of indie products that emerged in the dark days before Print On Demand and which collectively represented a sort of proto-OSR movement, celebrating dungeon bashing even as the hobby was moving in moody, exotic and cerebral directions in the wake of games like Vampire: The Masquerade and D&D projects like Planescape. Forge can be criticised for being derivative of D&D in the areas where it isn't innovating. But that's a good thing if it means that Forge's combat system, magic and adventuring assumptions map quite nicely onto the 1st Edition D&D/Labyrinth Lord rules undergirding Barrowmaze. I've even got a Forge/D&D monster converter on this website. Where Forge does diverge from D&D is in its setting: a world where the gods are all dead or exiled, there are only two types of 'cleric' and there are several unusual options for PC races (or is it species? well, you know what I mean!). Forge gives us fairly conventional Elves and Dwarves and its Sprites are essentially Halflings with magical empathy powers. Gigantic one-eyed Ghantu and pig-faced Higmoni fill the orc/half-orc slot. Berserkers are goliaths (but Forge predates their appearance in 3.5ed D&D). Next up, the oddballs. The sun-fearing albino Dunnar have innate magic detection, but look creepy and shuffle awkwardly. Then there are the animal-inspired lineages. The weasel Jher-em have prehensile tails and terrible asthma. The scaly Kithsara are innately magical. Bird-person Merikii are ambidextrous but, alas, cannot fly. Adapting the Setting: HelixHelix is the village on the edge of Barrowmoor that is the jumping off point for adventurers. Its name is odd, but probably suits the vaguely SF Forge better than the trad fantasy D&D. Author Greg Gillespie is very fond of exploring religious allegiances and conflicts in his settings, notably between the New Gods of civilisation and the Old Gods of the wilderness and the earth. An important deity is Nergal, the death god murdered by his demonic sons and whose cult built the vast funerary complex of Barrowmaze. Helix has a new shrine to St Ygg, one of the civilised gods of light and law, but many locals still venerate Herne the wilderness god at a nearby stone circle. Forge also has a 'dead' death god - Necros - and two more gods who are literally in Hell, but all the other gods have been banished by the wrathful (but strangely distracted) supreme being Enigwa. I've got a detailed analysis of Forge's unusual mythopoesis here. It's straightforward to treat Nergal as Necros, which makes the Barrowmaze a site that pre-dates the God's War, from a time before Necros turned to utter villainy. St Ygg has clear corollary with Forge's Berethenu, the god of Law and Justice with magical healing magic and a mission to exterminate Undead - who is currently burning in Hell. But it might be more interesting to link St Ygg instead with the worship of Enigwa the Supreme Being. Enigwa's religion could best be described as Deism: the belief in an all-powerful and moral creator who does not answer prayers, grant revelations or intervene in the world he has made. In Forge's world, this sort of religion would promote Humanism, education, self-reliance and philanthropy. We know that Enigwa forbade teaching magic to mortals; author Mark Kibbe's other books describe the Church of Enigwa persecuting mages. This makes sense if the Church of Enigwa is promoting science, reason and community enterprise over superstition, magic and individual glory. A very worthy religion indeed and one you could imagine running a small school and infirmary in Helix. No healing magic from Brother Othar and his acolytes though - but presumably high levels of medical expertise. Who or what then is being worshipped over at the stone circle three miles outside town? It makes sense that Grom the (also Hell-bound) war god might have been someone the villagers turned to for defence before the Church of Enigwa turned up. Perhaps Brother Othar drove out the Grom Warriors who lorded it over this place, but villagers are still inclined to call on Grom when some undead horror shambles out of Barrowmoor. Education and Humanism are lovely things, but sometimes you need a sword reeking of hot blood. In a setting like this, virtuous Berethenu Knights must keep a low profile and perform their healing magic discretely. Valeron the Elf is likely to be such a one. Perhaps the Church of Enigwa looks the other way if Berethenu Knights donate their charitable tithes to the local school and infirmary. But if a Pagan Mage draws attention to herself with public magic use, Brother Othar will petition Lord Ironguard have that Pagan fined, put in the stocks or even gaoled in Ironguard Motte. Actually, he'll petition the Jher-em vizier Ollis Blackfell (why make him Jher-em? well Ollis is described as "a weasel-looking fellow"). I think I'll turn the local magic-user Mazzahs the Magnificent into a Kithsara Enchanter. My take on these lizardfolk is that their cold bloodedness makes them philosophical and scholarly by nature. Mazzahs teaches occasional classes at the school in return for being left alone to practise Enchantment - but he can't afford to advertise his magic too loudly. That will do for now. I'll post up session reports for the exploration of Barrowmaze and also how Forge fares as a surrogate rules set for this sort of mega dungeon bashing.

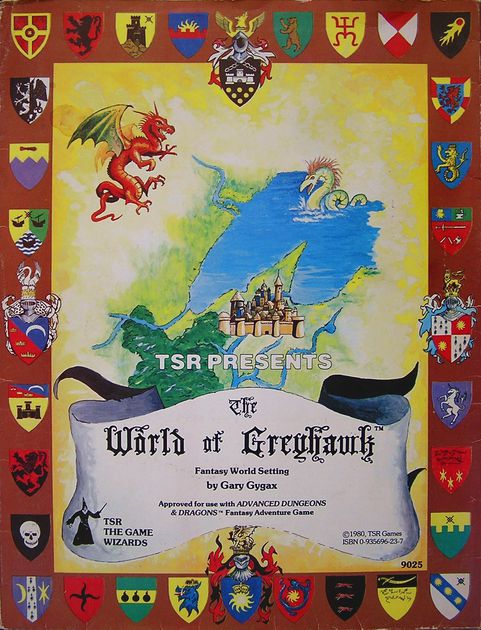

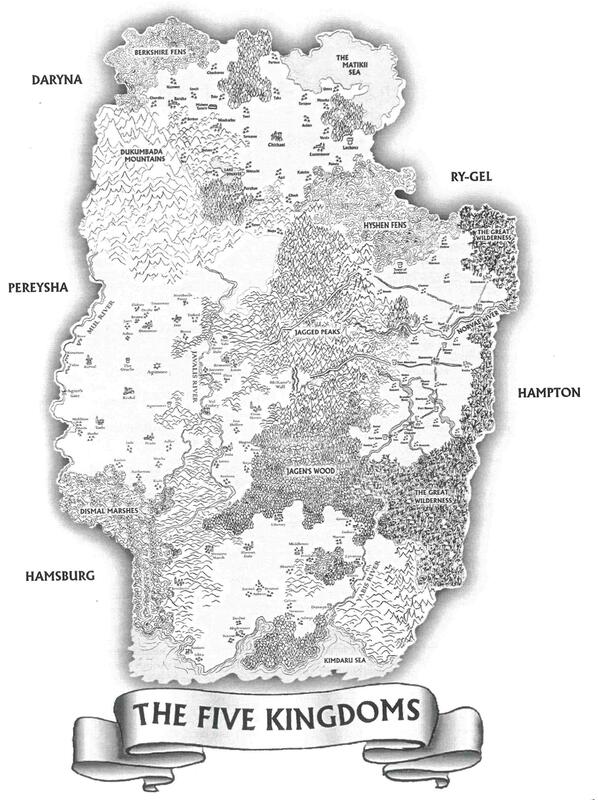

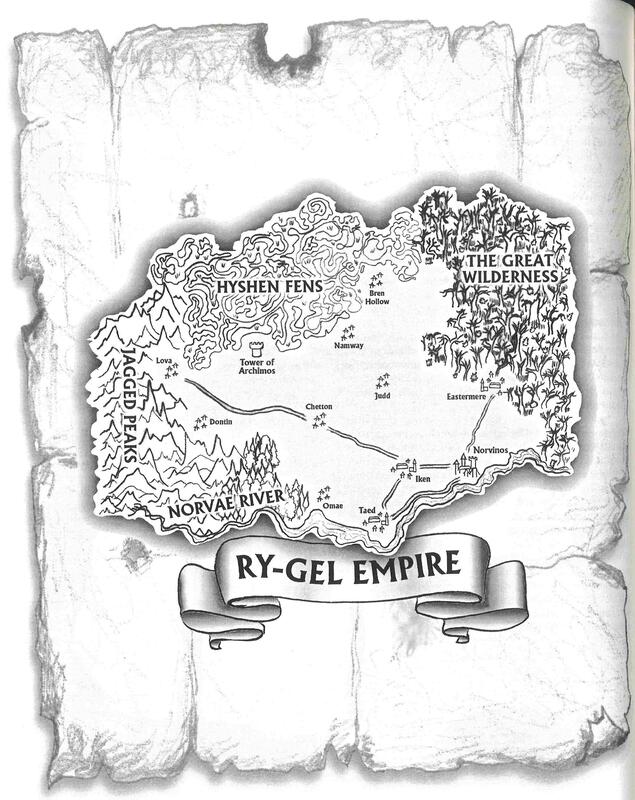

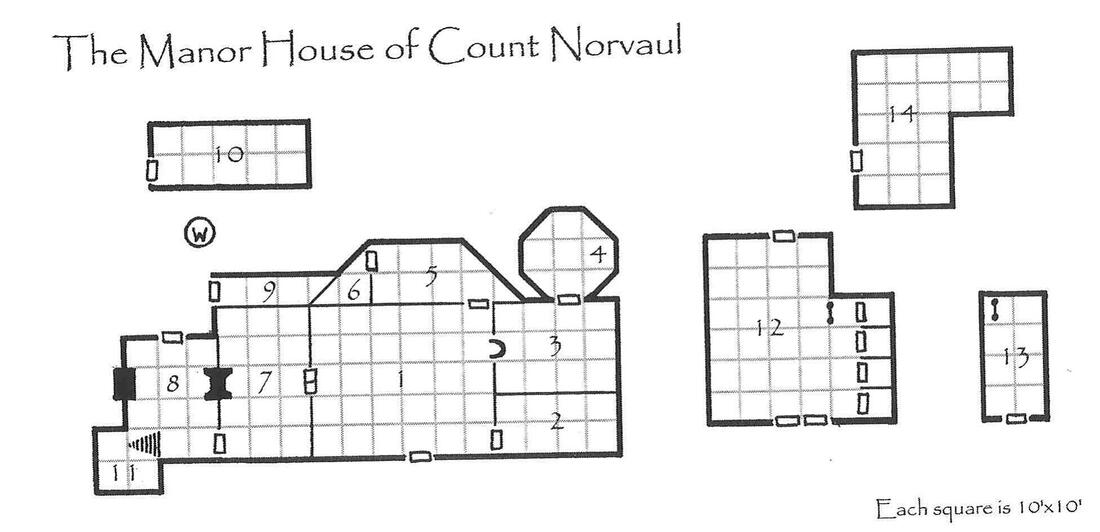

Over the past few months I've reviewed the 1990s "fantasy heartbreaker" Forge Out of Chaos and analysed its main rules, themes, monsters and the two published scenarios (The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell). It's a game with an identity crisis, setting itself up as a meat-and-two-veg dungeon crawler set in a ruined world where the gods have been banished, but then being recast as a sort of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay imitator, set in a Renaissance or Baroque world with a lot of politics, economics and a Gothic palette. More on that shortly. This is the last product to be published for Forge Out of Chaos, back in 2000. The previous module promised an ambitious campaign pack (called Hate Springs Eternal - great title) in November 1999, but that never appeared. Instead, the sourcebook arrived, rather optimistically bearing the "Volume 1" subtitle. After that, the presses at Basement Games fell silent. I wonder what was planned for Volume 2? The World of Juravia is a 170 page book that retailed for $19.95 - expensive for back then: this is the same price tag as the original Forge rulebook itself. The old team of Mike Connelly & Don Garvey is gone; there's a range of art in here, notably Jim Pavalec, who does the cover art, and Shella Haswell, who produced the back cover and has a rather different, highly stylised approach. The interior art varies a lot in quality but is mostly solid fantasy fare. Pavalec's cover suggests a return to the game's conceptual roots: a sinewy, barbaric figure (a Higmoni, judging by that be-tusked jaw) is ambushed by a many-headed snake (perhaps a Tursk, but they are supposed to have two cobra-like heads). The stylised nudity, the languid athleticism and the rearing monster, all seem to reference Boris Vallejo's art for Conan (minus the naked chicks: to its credit, Forge never went in for that aspect of old-school fantasy art). Gone are the breeches and lacy collars worn by the villagers in The Vemora: this looks less like 17th century Europe, more like pre Ice Age Hyborea. This statement of muscular intent is backed up by the back cover blurb: Welcome to the World of Juravia ... a paradise lost! Once a land graced with beauty, it is now a scarred wasteland of desolate swamps, jagged mountains, and hideous creatures beyond imagining. This echoes the contextual fluff on the back of the original rulebook: It was once a paradise but is no longer! Once beautiful landscapes are now swamps, desolate wastes and jagged mountains. The calm and gentle rain has turned to fierce storms of fire and ice. It's tempting to read this as a return to the game's roots in a gritty post-holocaust environment, rather than the genteel and civilised setting described in Tales That Dead Men Tell. What's inside? - A Calendar! Yes, we start with the Juravian Calendar and it appears to be the year 679: that's 679 years since the gods were Banished. The first 300 years seem to have passed in murky confusion but in the last two centuries there has been some sort of Renaissance and an international calendar has been developed. Four pages set out the days and months of the Juravian year and its major festivals, which honour the gods, especially Omara, goddess of harvests. There is reference to the "church of Enigwa" (the creator-god) and its year-end tradition of burning alive all wizards! Let's dispense with the oddity of kicking of your world-building sourcebook with arcane stuff about calendars. Gary Gygax did it with the 1st edition AD&D World of Greyhawk Gazetteer and if it's good enough for Gary... Yes, I assume that author Mark Kibbe followed (rather uncritically) Gygax's AD&D template for what a world sourcebook ought to look like. Critic Ron Edwards rages against this sort of thing, complaining, in his famous essay on Fantasy Heartbreakers (2002), that games like Forge "represent but a single creative step from their source: old-style D&D." But I'm rather touched by the humility of it: Mark Kibbe is homaging the World of Greyhawk, right down to Gygax's highly idiosyncratic ersatz-scholarship. But never mind that! The eye-rubbing is in the details. What was implied in the previous modules is explicit here: in Juravia, the gods are still being worshiped and that worship is led by a professional priestly class. To grasp the weirdness of this you have to steep yourself in Mark Kibbe's iconoclastic mythology - but since his mythopesis takes up the first 11 pages of the Forge rulebook, you'd be forgiven for supposing the author wanted you to do exactly that. These are the gods (let's recall) who joined together to create humanity, then set about warping and mutating humans into the demi-human races and into monsters to function as soldiers and artillery pieces in their planet-shattering war, a war which led to their banishment from Juravia, the utter annihilation of one of them and the eternal perdition of two more. Why would anyone who believed this mythology want to worship these beings? And since they cannot answer prayers or grant spiritual comfort, what would be the point? It makes sense that creator-god Enigwa would stll be worshiped and it makes sense that his 'church' would condemn Mages: in Juravian myth, Enigwa forbade the gods to teach magic to mortals. You would think the Enigwa-ists would be just as hostile to the worship of other gods, especially Gron and Berethenu, since Enigwa sentenced these two deities to Mulkra (Hell) for their role in the God-Wars. If the "Church of Enigwa" promotes Deism (the belief in a virtuous but non-interventionary God) and indulges in Wizard Burning, then we are very clearly in the equivalent of Europe's 17th century here. I don't mind that: a world inspired by the Witch Trials of Bamburg and Salem has appeal. But I'm surprised. The main rulebook gives no intimation that Mages are hated outcasts or that anyone choosing a Mage profession is putting a target on their back, courtesy of those fanatical Enigwa-ists. Moreover (and this is oddest of all), the rest of the gazetteer barely refers to it again. The Five Kingdoms - sort-of France, or maybe Massachusetts There's a map of the campaign setting of 'the Five Kingdoms' and it is (for its time) nicely done and in the same format as Tales That Dead Men Tell. There's a massive central mountain range (the Jagged Peaks) and the Dukumbada Mountains up to the north-west, creating a passage between them linking the northern and western regions. The northern kingdom is Daryna, which is suggestive of Poland, bordered by dense swamps and a sea coast. The Merikii bird-people live here and it's pretty isolated. The region is not an island - rivers, mountains and forest form natural boundaries Over to the West is a large 'empire' called Pereysha, bordered by rivers and more marshes. It seems to have a sort of Franco-German feel. There's a massive forest south of the Jagged Peaks called Jagen's Wood and that separates Pereysha from coastal Hamsburg, which was the setting for Tales Dead Men Tell and is perhaps Mediterranean in tone. East of Jagen's Wood and the Jagged Mountains (but connected to Pereysha by a strategic mountain pass) is Hampton, the setting for The Vemora; however, this version of Hampton makes no reference to a 'High King' called Higmar and the village of Dunnerton does not appear on the map. Finally, north of Hampton but cut off from Daryna by the enormous Hyshen Fens, is weird Ry-Gel, which I'll discuss in a bit of detail, since it's the most clearly fantastical of the realms. The map is only a sliver of a wider continent. No scale is given (an odd oversight) but based on the textual references, the region seems to be about 500 miles east-west and twice that north-south. In other words, these 'empires' and 'kingdoms' are squeezed into a territory the size of France. Off in the wings, beyond the map, are the larger polities of Jucumra and Brattlemere and an Elvish realm of Elladay; however, natural barriers (especially the 'Great Wilderness' to the east) lock this territory off from the wider world. The Merikii are the indigenous peoples of Daryna, but the other kingdoms are former colonies of those off-stage empires. This starts 491, with Hampton being founded by pioneers from Jucumra making their way through the Great Wilderness, like Daniel Boone crossing the Cumberland Gap. The Jagged Mountains are seething with Higmoni War Camps and in 533 these erupt out, causing the Blood Wars. Various offstage empires contribute troops and the victors carve out Pereysha over on the other side of the mountains and then Hamsburg, a Pereyshian colony, wins its independence in a brief revolt in 587. Ry-Gel seems to stand apart from these events. It is discovered by pilgrims crossing the Great Wilderness in 301, a bit like the Mormons arriving in Utah, and it fights its own battles with the Higmoni a couple of centuries before the Blood Wars, then it falls under the rule of a wizard named Nanghetti who becomes a usurper and has to be destroyed by an order of paladins. Ry-Gel stays out of the Blood Wars but is rocked by famine and plague. it bans all religion and is ruled by a corrupt and decadent Triumvirate. It is far and away the most interesting of the Five Kingdoms. Nanghetti's return from the dead was supposed to be the plot for Forge's module-that-never was, Hate Springs Eternal. The Ry-Gel 'empire' seems to be about the size of Wales Analysis The names are, I think, misleading. Pereysha is called an 'empire' and so, on occasions, are the other realms. Secundum literam, they are not: they haven't expanded beyond their national borders to conquer or colonise other peoples; they're not multi-ethnic supra-states. Calling them 'kingdoms' also seems to be hyperbolic. They're more like the duchies of Medieval France or the protectorates of Renaissance Germany. No, what they are really like are the early American colonies. Hampton, with its robust citizen militias, gender equality and big university would be Connecticut; Hamsburg with its archaic gender roles would be somewhere like Catholic Maryland; Pereysha is big, rich Virginia with its trade ties to the Old World. Daryna is isolated and full of 'natives': the Great Plains, maybe Oklahoma. Weird Ry-Gel with its pilgrims and paladins and reactionary secularism could be Quaker Pennsylvania or Puritan Rhode Island. This piece of interior art seems to me to capture the tone of Mark Kibbe's setting better than strapping barbarians or robed wizards The US Colonies analogy gives me a clearer sense of what author Mark Kibbe was reaching for. These aren't barbaric territories, despite the front cover art, but they border onto unexplored and dangerous wilderness regions. The 'kingdoms' are small in population, experimental in political structure and have a relatively short history. They're all related to each other. They're all friendly. Moreover, they're economically productive and intensely liberal. Yes, there are few quirks, like Hamsburg's treatment of women and Ry-Gel's treatment of religion, but these are very modern cultures. All of them win their independence more-or-less bloodlessly because their parent empires prefer to trade with their former colonies than hold them by force. It's like an American 'civics' class with monsters. Bad rulers are deposed, usually peacefully, by dissatisfied commoners. Ordinary people go to university. Official documentation entitles people to travel and trade (it's not clear if the printing press exists, but the political sophistication surely suggests it does). It's all quite idyllic. Which, of course, makes it a bit dull. The troubling idea of a 'Church of Enigwa' persecuting Mages is never touched upon again. Sure, bureaucratic Pereysha can be a bit burdensome for free-wheeling PCs, but despite the exemplary detail in the regional descriptions, there's very little conflict for players to get caught up in. There's not much ethnic hate, or unresolved grievance, or seething discontent. The worst people in the Five Kingdoms are the 'Rats Nest', a Thieves Guild that destabilises the Hamsburgian Province of Newton. The Rat's Nest gets a thorough description, but you still don't feel motivated either to join it or destroy it. Ry-Gel is a bit of an exception, with its mystical past, it's unusual (and corrupt) government and its intolerant laws. You can feel adventures brewing in Ry-Gel, if a covert missionary wants to preach some crazy new faith and recruits the PCs as guards - or if the PCs get recruited as inquisitors to root out cells of cultists. But the main problem is lack of cultural focus. Every village and town gets a small entry, each leading NPC gets named, but the world of the Five Kingdoms remains shadowy. There's a solid idea for a setting here, but Kibbe focuses on the peripheral details and lacks the insight into human darkness needed to imbue his world with conflict and drama. Kibbe seems to struggle to imagine that rational people wouldn't sit down and solve every problem peaceably, so that's what his NPCs tend to do. It's a world that feels SAFE and not in a good way. The Dungeon Architect The next section of the book is the Dungeon Architect which appears to be made of material originally posted on the Basement Games website. There are 24 locations, each with a clear map and key, background and suggestions for inclusion in a campaign or using as the basis for a scenario. One of the larger locations, an abandoned manor house in Hamsburg that is being auctioned off by the state and could be bought by PCs for 157gp (you see how orderly and cosy this setting is? no need to bribe clerks or flatter aristocrats in sensible Hamsburg!) The selection includes inns, abbeys, the University of Nyanna, abandoned hermitages, crypts, cave systems and temples of Grom. The value of this sort of thing is immense, offering day-to-day locations where the PCs live, relax, work or research along with more mysterious locales that an be the basis for adventures. Mark Kibbe's rather prosaic imagination is ideally suited to this sort of architecture: lots of maps, sensible room descriptions, attention to details like estate income and access to fresh water and a few rumours and legends. An entire book of these would be invaluable for anybody's campaign, using any system. The last six pages of the book are taken up with a 'Rumours' section, which also seems to have come from Basement Games' website, presumably reflecting the designer's house campaign with contributions from some of the game's fans. These are fine: any and all could serve as plot-hooks. But none of them is particularly striking: there's nothing eerie, baffling, horrifying, intriguing or epic going on in Juravia: just expeditions, bandits, criminals on the run, missing children, kidnappings, tax collection and (this is good) the burning of a magic-wielding infidel by the Church of Enigwa. You want to know more about this Mage-hunting Church and less about tax collection, but as usual the setting seems to focus on all the wrong things. Amnesia - the last scenario We never got to see Hate Springs Eternal, but the Juravia sourcebook includes the third and final Forge module, a scenario called Amnesia which holds its head up well alongside The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell, i.e. it's the sort of thoughtful, low-key adventure that would have been a classic if White Dwarf had published it in the '80s but which lacks the ambition or originality to rescue the Forge franchise from obscurity. The premise here reminds me of the old AD&D Module A4: In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords. The PCs awake in an underground cavern without their equipment and must find their way out, relying more on wits and roleplaying than conventional combat. Erol Otus' art is so witty: the PCs beat down on some small mushroom people but look what's approaching in the distance... In Amnesia the situation differs slightly: the PCs have armour and weapons but do not have any memory of where they are or how they came to be there. The scenario functions as both a trap and a puzzle, since the players must figure out what has been going on from clues they come across underground - including an angry Dwarf who knows them well and has good reason to hate them, although the PCs have no recollection of meeting him before. It's only 10 pages long, but the detail, layout and plotting is faultless. Mark Kibbe excels at this sort of thing: the classic dungeon-based scenario, done well. The players start off with limited light source and no map-making equipment and will soon find themselves in darkness, going in circles, unless they are clear-headed. Soon, they will acquire much-needed equipment and start to piece together that they are in a slave camp, with formerly-brainwashed prisoners who have been working the copper seam. The mine contains dangers of its own as well as shocks when the PCs discover that, in that period of their lives they have forgotten, they were not the slave workers in the mine but the cruel guards and overseers! There are several possible exits, one of which involves a very nasty fight with armed and armoured guards (always a tricky proposition given the way Forge's combat system works) and the other two involving an element of roleplaying with distrustful or hostile NPCs. The scenario concludes with some intrigue and politicking. The mystery is explained by the activities of one of the monsters from the Forge rulebook - a Limris, which I've previously singled out as the most original and entertaining contribution in the entire bestiary. The creature has been in cahoots with a leading Merikii Duke of Daryna, so in the aftermath the PCs are either going to accept a mighty bribe to stay silent about the Duke's involvement in kidnapping, slave labour and monster-wrangling or else set out to bring the villain to justice. Don't mess with the Merikii All of which is to say, this is A Very Fine Scenario Indeed. It could comfortably fit into two sessions but it might expand to more if the Referee expands on the aftermath. It's nice to see Merikii rather than Higmoni as antagonists (although the poor old pug-faces turn up here as well as thankless monster mooks). It's a bit more challenging than The Vemora or Tales That Dead Men Tell, offering situations and dilemmas that will put more experienced players through their paces. And yet, it falls short of what it needs to be. Kibbe takes a pride in modest threats: all three scenarios for Forge are self-consciously low-key affairs: no demons, no powerful mages, no dragons or vampires, no ancient curses or powerful relics. In this scenario, the main monster, the Limris, dies offstage - like the non-appearance of the Cavasha in The Vemora and the absence of scheming Maria Yates in Tales That Dead Men Tell. Kibbe seems to delight in creating big melodramatic plotlines and then locating his scenarios in their shadow: the players hear about but never get to meet the fantastical fiends. Yes, there's a pleasure in this sort of approach - like the 1994 "Lower Decks" episode of Star Trek Next Generation. The problem is that this sort of subdued, tangential narrative is all Kibbe ever produces. It's a bit like watching Rosenkrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead without having seen Hamlet - you haven't seen the real thing of which this story is the artful deconstruction. After three modules, we still don't know what a proper Forge scenario is supposed to look like, what the game has to offer when taken at face value. I would happily referee Amnesia as an introduction to Forge for experienced players - and it would convert very easily to D&D or other classic Fantasy RPGs - but it just isn't the sort of scenario that this product needed to sell the rather opaque 'Five Kingdoms' to an increasingly sceptical fanbase. Overall - how should we look back on this? Of course, Forge Out of Chaos passed away and this was its last gasp. Probably, the writing was on the wall for Basement Games back in 2000, but perhaps Mark Kibbe was sincere in his hope for further support for the game. But, no: Ron Edwards (2002) analysed 'fantasy heartbreakers' like Forge as doomed from the start by economic realities as much as by their shortcomings as products in a crowded marketplace. I'm glad, though, that Forge got this far and that Mark Kibbe was able to deliver his RPG vision. There is much to commend it, but it illustrates an important lesson in creativity: focus. Kibbe never seemed to grasp what was distinctive about his game or his setting. Forge clearly began life as a post-D&D homebrew that reached an unusual level of sophistication and completion. Kibbe himself moved away from conventional dungeons and monster-baiting, in favour of more thoughtful scenarios. His setting moved away from a barbaric post-holocaust world to a civilised but precarious frontier, with hardy colonists carving out their prosperity in the midst of a vast wilderness. Yet he failed to capitalise on these features. The Church of Enigwa, which goes around burning wizards as infidels ... a world where the gods have been judged and condemned .... a society built around trade routes and trade wars ... a system of travel documents, official permits and bureaucratic paperwork ... guilds and thieves rather than monsters and demons ... This is not like a standard Fantasy RPG setting, yet all this stuff is hidden away in the margins or must be inferred by a diligent reader. There's a good campaign to be had in Juravia, something distinctive and distinctively American, but you feel that, even at the end of the product line, designer Mark Kibbe hasn't quite figured out what it is yet.

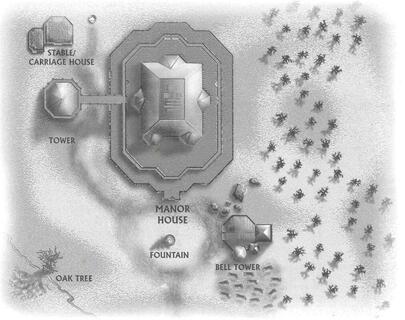

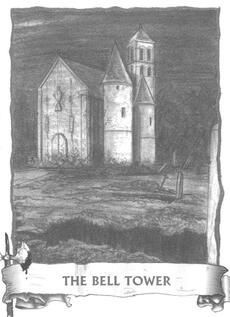

Tales That Dead Men Tell (hereafter, Tales) is the second and final scenario published for Forge Out Of Chaos by Mark Kibbe back in 1999. It retailed back then for $9.95 and consists of a 46-page staple-bound book with colour cover art (by Jim Feld) and some B&W interior art (also by Feld, a departure from the team who worked on the original rulebook), including regional and local maps by Steve Genzano and lots of illustrations of NPCs and enemies discovered during the scenario. Tales isn't available as a PDF through DrivethruRPG but there are a lot of copies for sale online, from as cheap as $3 from some book sites to a typical $6 on eBay. First glance shows Tales to be a more ambitious project than The Vemora (1998). Gone is the cartoony artwork of Mike Connelly and Don Garvey: Feld's moody and murky illustrations set a more crepuscular tone that fits the spooky theme. It's a more mature and professional style and it definitely gives reptilian Kithsara and bestial Higmoni a much more distinctive look. Jim Feld (left two) compared to Higmoni and Kithsara by Connelly/Garvey Connelly and Garvey homaged 1980s D&D with their style, but Feld is a step onwards and upwards, offering Forge its own visual identity - yet I can't help feeling that something charming has been left behind. In fact, much has been left behind, as we shall see. Background And there's a lot of this. Whereas The Vemora was set in a rather hazy fantasy kingdom with a distant High King and a local Village Elder, Tales is rooted in the detailed history of the Kingdom of Hamsburg, which seems to be pitched to us as Forge's default setting. I'll have more to say about Hamsburg and the Province of Lyvanna later on. Suffice to say, this is a territory that has won its independence from being an imperial colony and is the sort of trade-hungry border region that fantasy RPGs seem to gravitate towards. More relevant is the recent history of thief-made-good Kamon and his ambitious wife Maria, a woman combining the more extreme traits of Cersei Lannister and Scarface. While Kamon works like a dog building up a mercantile business, Maria constructs a criminal empire under the cover of his honest dealings, offering Kamon Manor out as a safe house to the Rat's Nest, a nasty band of villains. When the Law comes calling, poor old Kamon is executed, one of Maria's sons is killed and Maria goes to gaol, leaving her youngest son to expire all alone, locked in the cellar. The Manor is subsequently haunted by the ghost of Maria's betrayed husband and her abandoned son. That was all a generation ago, but now a team of Necromancers has arrived at the Manor with some mercenary Higmoni (it's always the Higmoni...) in tow. They've suppressed the hauntings by ringing a mystic bell and ambushed the local militia sent to investigate the strange goings-on. They're looking for Kamon's fabled treasure, hidden somewhere in the house. The Hook The PCs are the usual swords-for-hire and are recruited by an elderly merchant who rejoices in the astonishing name of Aberdeen Jenkins. Jenkins has bought the Kamon Manor estate as a fixer-upper but needs the adventurers to sort out the mystery of missing militiamen, ghostly bell-ringing and sundry hauntings. Simple as that, really. Do some research in Lyvanna into the Manor's history then get down there and clean the place out of troublemakers. Jenkins is paying 500gp for this bailiff-work and - weirdly - is prepared to let the adventurers keep any treasure they find on his estate while they do it. That's a bit mad, but I'll suggest a more rational offer for Jenkins to make later on. Research in Lyvanna As well as a simple 'rumours' table, Tales invites you to explore the town of Lyvanna and interview a selection of NPCs about Kamon Manor and its unlucky history. This research phase gives the scenario a bit of a Call of Cthulhu vibe, although it sits somewhat oddly with Forge's system, which doesn't offer players any social or research skills. Ron Edwards (2002) summed up Forge as a game that was "gleefully honest about looting and murdering as a way of life, or rather, role-playing." I think he exaggerated, but Tales' shift away from dungeon-bashing towards investigation and negotiation is a clear departure from the ideas that were noticeable in the rulebook. Whether Forge's mechanics really support this style of gaming is another matter... Roaming around Lyvanna, the players can interview the helpful Dunnar sage Xavier Pratt, the helpful local lord Bromo Lionheart, the helpful militia leader Captain Honis, yes, everyone in Lyvanna is very helpful. Now don't get me wrong, I don't like grimdark settings where everyone is backstabbing everyone else, but these NPCs are intensely static: the designers give each one a distinctive behavioural quirk, but none of them has an agenda or a subplot to offer. They're just waiting for the PCs to turn up so they can deliver their exposition. Perhaps sensing that their setting lacks dramatic conflict, the designers present a pickpocket and a conman for players to interact with and some agents of the Rats Nest who will start dogging the PCs' footsteps. More about them later. Off to the Kamon Estate Once on the grounds of Kamon Manor, the PCs can wander freely by day or be harassed by Giant Bats at night. If they take cover in the Bell Tower and kill or chase away the Higmoni guard, there will be consequences: with no one ringing the bell, the ghosts of Kamon and his son resume haunting the site. Superior maps and tone-setting art, compared to The Vemora from the previous year The Manor House is an old fortress and entering it will tax the players' ingenuity. The front gate is guarded by more Higmoni but the walls can be scaled and the side tower accessed through a bridge. There's a prisoner to rescue in there (an unlucky Rats Nest spy) and a dangerous monster, a Vohl (which is a sort of taloned ghoul, as opposed to a vole, which is a cute water rat). Exploring the house is a tense affair, especially if Kamon's ghost is active, whispering creepy things, pushing people down stairs and dropping statuary on passers-by. There's a chipper Sprite adventurer also moving through the house: Theo Bratwater will join the party and be either useful or annoying, depending on how the Referee plays him. There's a militia man to rescue, two Necromancers to tangle with, plenty of Undead and the Higmoni captain who might leave without a fight if approached correctly. There's also the ghost of Davis, Kamon's tragic son, who appears to be a normal kid and a helpful guide until you stumble across his corpse in the cellar. The main bosses are the Necromancers: Chiassi the reptilian Kithsara and Berria the Elf. These two are presented with spell lists in full and demonstrate the crunchiness of the Forge system, offering the Referee plenty of choice, both in roleplaying their reactions and selecting their most effective tactical responses. Chiassi: check out his feet! Hopefully, the players discover the documents exonerating Kamon and lay his ghost to rest. On the way home, those three Rats Nest spies (remember them?) ambush the exhausted party, prompting a final act battle. Evaluation: non-Forge As I've discussed elsewhere, Forge converts painlessly to older iterations of D&D and even 5th ed conversions shouldn't pain anyone too much. The Higmoni are Orcs or Half-Orcs, the Necromancers are Chaotic/Evil Clerics, Zombies and Skeletons are Zombies and Skeletons, the Ghosts don't require stat blocks and the other dangerous animals or carnivorous plants have easy-to-source analogues in various Monster Manuals. The Vohl would be 7HD, AC 4, 3 attacks for 1d6/1d6/1d2 (Save vs Death Ray or lose those 1d2 HP permanently), MV 15" or 150' (50') - a nasty opponent for low-level characters. It's a tougher scenario than The Vemora in terms of the number of monsters and the spell-casters: probably better if most or all of the PCs are 2nd level rather than 1st, maybe with a 3rd level Thief on board. But that, I suppose, makes it a good follow-up to the earlier dungeon. Do you need it, though? The Vemora was a fantastic tutorial dungeon with enough dangling plot threads to prompt me to write an expanded version of it. Tales feels less essential. On the positive side, it's an intelligent explore/destroy mission and Mark Kibbe has a talent for dungeon layouts that generate drama. The presence of the tragic ghosts lends an element of spine-tingling mystery to things. The maps, NPC portraits and caption boxes are all attractive: if the whacky or primitive art of the earlier books repelled you, you will feel you're in the hands of professionals now. On the other hand, the stakes are quite low. You're bailiffs for Aberdeen Jenkins (that name!!! I'm in love!), turfing out trespassers on his land. It's not glamorous. It reminds me of the sort of thoughtful scenario White Dwarf used to publish in the UK in the 1980s - or the AD&D module U1: The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh (1981); the one that sent the PCs to a haunted house that was really a cover for smugglers. The "Scooby Doo episode of D&D modules" according to Ken Denmead (2007) vs the 1986 WFRPG Or, perhaps, a better fit is Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, with its dark fantasy-Europe setting: any story in which a wealthy merchant sends you up against evil cultists and a vicious guild of thieves has a clear WFRP vibe going on. WFRP delights in its low-fantasy theme, its dark low-key dramas and tragic backstories. But of course U1 shifts its action from searching the old Alchemist's House to raiding the ship Sea Ghost, whereas Tales doesn't really go anywhere: you don't get to track down the Rats Nest and punish them for their perfidy. The space in the booklet is taken up instead with fluff about Hamsburg and Lyvanna, which I don't think most DMs will be making use of. So let's talk about the setting. Sensible Settings, Yawn... The cover of The Vemora surprised me with its Tudor buildings, lacy collars and breeches. Tales shows that the 17th century tone was quite intentional. This is not a Dark Ages or even Medieval world. It's Renaissance or perhaps Baroque. The various kingdoms and empires are stable, with parliaments and universities. Government exists "to uphold the welfare of the commoners" (p10), which is as clear a statement of Humanism as you could wish for. The focus is on tariffs and taxes, laws against "unfair trade practices and economic collusion" and revolts that remove oppressors from power. In other words, far from being dystopian, Hamsburg seems like a lovely place. You cannot imagine giant flightless birds, enormous man-eating beetles or two-headed super-snakes marauding across this landscape. Maybe a dandy highwayman inconveniences travelers, but never a dragon. It's the sort of setting that makes Tolkien's Shire look gritty and morally ambivalent; the politics are more cut-throat in Narnia! Mark Kibbe offers one concession to cultural darkness, which is the Hamsburg seems to treat women poorly. Kamon's wife Maria barters herself into marriage and criminal dealings in pursuit of power and autonomy in a world the treats her sex as chattel. The problem is that Kibbe's imagination is so genial that he forgets his world is supposed to be like this: we are told Maria's teenage daughter survives the fall of her family because she was off at University at the time. How very progressive! Look, I don't mind idealised fantasy settings, but there seems little point in describing their political settlements if there are no important conflicts going on. Conflicts don't have to explore the dark side of human nature: some people are greedy, fanatical, jealous, cowardly or filled with hate; others are generous, idealistic or desperately in love. Nobody in Lyvanna seems to be doing anything, good or bad, except the Necromancers, and they're just cartoonishly evil. Evaluation: Forge The positive is that Tales is a step forward for Forge in many ways: in production values, story complexity, world-building and so on. The downside is that not all of these steps develop what was noteworthy and interesting about Forge in the first place. The original Forge rulebook boasted a hell-on-earth setting, ruined by the gods with mortal races left behind to survive in a dystopian world. The monster Bestiary resembled Gamma World's collection of mutants and horrors more than a conventional fantasy monster manual. The PC races were exotic and rather primitive. The rules embraced dungeon delving and tactical combat, with few skills or spells for politicking, negotiating or carrying out deceptions. Tales takes place in a harmonious and rather advanced world that resembles (to my mind) the New World colonies in the 17th century and the cosier parts of Reformation Europe, far away from the 30 Years War or the Witch Trials. Everybody seems to be human, with a few Elves, Dunnar and Kithsara as 'exotics'. One cannot imagine giant one-eyed gorillas or telepathic weasel-people moving through this society. The naming conventions reveal much. In The Vemora, NPCs have names like Kharl Atwater, Brundle Jove, and Jacca Brone. The High King's name was Higmar. Solid fantasy names with a touch of otherworldliness to them. In Tales, we meet Maria Yates, Xavier Pratt and the incomparable Aberdeen Jenkins. These aren't bad names either, but they're very different names. They belong in our world, albeit to colourful people. The God-Wars have faded from the imagination and religion is back. Maria marries the hapless Kamon in "a small roadside church," the Province of Lyvanna is governed by "wealthy landowners and influential clergymen" and the local temple of Omara is "very small compared to the elaborate churches of larger towns" - in other words, this is Christian Europe, thinly disguised. Clearly, Mark Kibbe has matured and his imagination has moved away from the barbarian world of Forge towards a more sophisticated setting. That's fine. The problem is that Forge doesn't really support roleplaying in such a low-fantasy world. There are no illusion spells or skills for things like pickpocketing, faking signatures or seduction. Plus, your character is a giant one-eyed gorilla! Final Reflections There's a solid scenario here. It would be great adapted for WFRP but D&D players would enjoy it as part of the Saltmarsh campaign. The scenario creates a problem for itself that the passions and betrayals of Maria and Kamon's marriage and their gruesome ends are far more interesting than the events going on in the present. How much better the story would have been if the PCs were contemporaries of Maria: they could be employed by her to get her treasure back (only to be betrayed by her in turn when she strikes a deal with the Rats Nest), rather than acting as bailiffs for the soft-hearted Aberdeen Jenkins, decades later. In other ways, the scenario inspires fresh directions. In an earlier blog post I introduced the idea of Dungeon Constables or 'Dinglemen'. In this adventure, the PCs are themselves the Dinglemen, sent by the owner to evict trespassers from his 'dungeon'. The idea that the PCs keep the treasure they find there is absurd: it all belongs to Jenkins by right and the PCs are paid a wage to retrieve it. This introduces nefarious possibilities if the Rats Nest approach the PCs to fake an 'ambush' whereby the treasure is all 'stolen'; the PCs and the Thieves can later meet up secretly to divide it between them. Do the players take the deal and betray their employer Jenkins? What happens when the Thieves betray them and keep all the loot for themselves? The module's back page advertises an intriguing third module: Hate Springs Eternal, "coming in November 1999." This scenario sounds thoroughly epic, with an arch-mage returning from the dead and the PCs battling through an army to save the continent. A new type of Magic is promised! Alas, it was not to be. Tales turned out to be the second and last Forge module, leaving the game with a distinct identity crisis that is only deepened by the directions taken in the World of Juravia Sourcebook (2000), which I'll look at next.

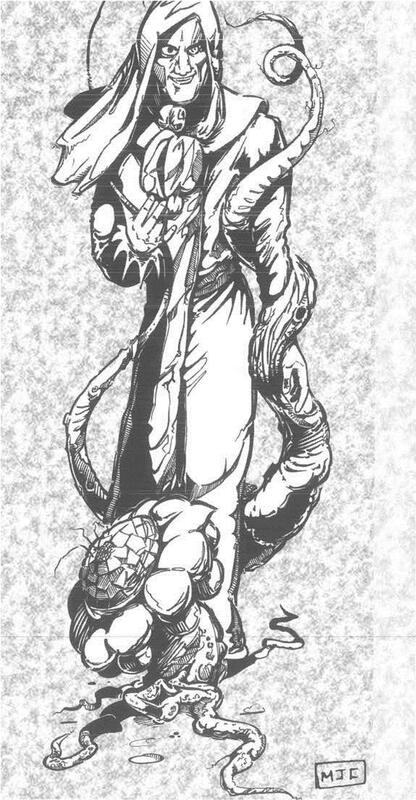

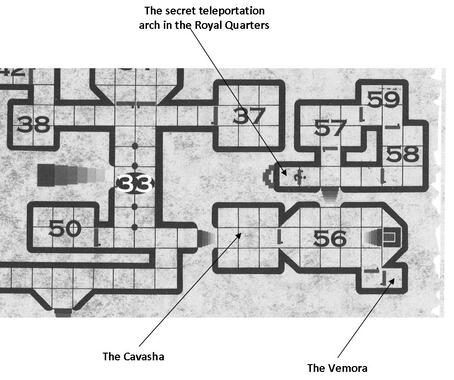

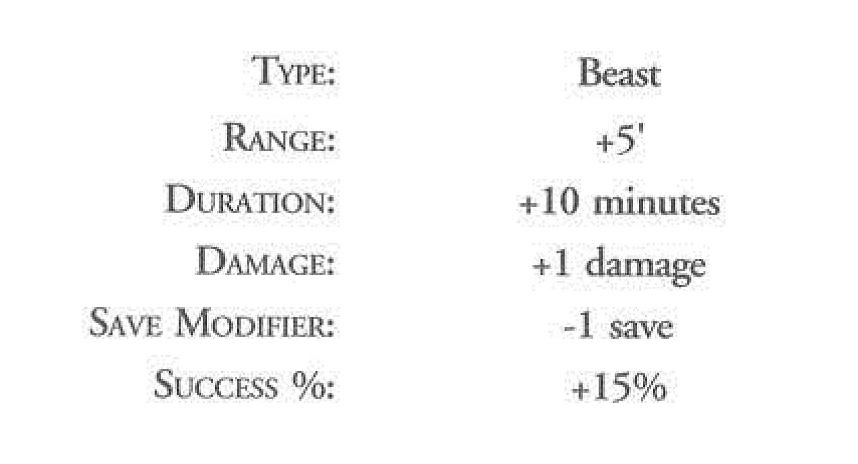

After reviewing Mark Kibbe's 1998 module, I set about expanding it in order to develop its dangling plot threads: what was the truth behind the deadly plague that brought down Thornburg Keep and resisted even the healing powers of the Vemora? what is Shirek the Ghantu doing in the Keep and what are his humanoid minions searching for? what happened to the Cavasha? how does all this fit into the Kibbes' mythology of banished gods? The expansion document is found on the SCENARIOS page. Paul Butler's lovely cover illustration of the Cavasha: alas, the scale of the houses is all wrong The Return of Galignen The Forge rulebook introduces Galignen as the god of Disease, but also of nasty plants (fungus, molds, slimes, etc). He's the younger brother of Necros (Death) and Grom (War) and joined their Triumvirate that tried to take over the world during the God-Wars. He is "deceitful and unscrupulous" and "despises mankind" which he looks upon as "insects" and he "twisted man into sentient flora." During the God-Wars he "unleashed pestilence and plagues, the most severe of which was known as the Rotting Death." Artist Mike Connelly's depiction of Galignen The rules list Galignen among 'Those Taken from Juravia' as opposed to Necros (cast into the Void) and Grom and Berethenu (banished to Mulkra/Hell). Why did Galignen get off so lightly, since he seems just as malevolent as Necros and as destructive as Grom? An idea for a Forge campaign could focus on Galignen: what if he escaped creator-god Enigwa's wrath and judgement by merging himself with Juravia's plantlife? For hundreds of years, Galignen has been present in Juravia, assumed to be banished but really just left behind. He has spent that time slowly recovering his sentience and a bare fraction of his divine power, perhaps inhabiting a giant fungus colony in a deep cavern, attended by a loyal cult. The secret of the Vemora There is more than one Vemora. The Vemoras are relics left behind by Enigwa in his wisdom to counteract the power of Galignen, should he have survived the God-Wars. The Vemoras' healing properties are side-effects of their true purpose: they are the spiritual locks that prevent Galignen returning in power. In order to regain his full divinity, Galignen needs to corrupt or destroy all of the Vemoras. The attack on Thornburg Keep's Vemora is just one manoeuvre in Galignan's plan, which has battles on many fronts. Galignen sent his own worshipers to Thornburg Keep, infected with the Red Rot, to close the healing sanctuary down. His next move is to retrieve the Vemora for himself. Unfortunately, the Red Rot drew on far more of the god's power than he calculated (and he was perhaps badly defeated in his attempt to retrieve another Vemora elsewhere). Galignen has spent 80 years recovering his power - but what is a century to a god? He is ready now to reach out and seize the Vemora. He has sent his worshiper Shirek the Ghantu to do this. When the Vemora is brought back to him, it will become Galignen's Chalice of Plagues, restoring a large measure of his power to create diseases. The Red Rot Galignen developed this plague in collaboration with his brother Necros. It is a hemorrhagic fever (rather like Ebola) which covers the poor victim in blood-seeping sores. Worse, the corpse of a victim is reanimated as a Plague Zombie. Galignen intended the Plague Zombies to overrun Thornburg Keep and bring the Vemora to him themselves. He was thwarted in this. The master Healer of Thornburg Keep was wise enough to burn the infected corpses and evacuate the Keep. Exhausted, Galignen allowed the plague to fall dormant. Now he's ready to try again, but this time he won't trust in zombies! Shirek and the Plague Cult Most of Galignen's cultists are sentient flora, but he has a few fleshy worshipers like Shirek and his Higmoni lieutenant Voork. The Higmoni's natural regenerative powers enable them to endure the Red Rot for far longer than other creatures: they believe that, if they are successful in their mission, Galignen will cure them, but they are surely mistaken in this. Shirek is a true acolyte of the cult and bears countless infections and fungal growths on his flesh, but Galignen's power makes him immune to them: he is the example of the god's power that inspires the Higmoni to put up with the infection they endure. However, should he succeed in his quest and bring back the Vemora, even Shirek will be abandoned to die or, at best, be transformed into a shambling plant. Shirek has set his minions to work ransacking the dungeon, looking for the three keys that unlock the Vemora, but has so far come up with nothing. Worse for him, the Cavasha has set up its lair in the Keep and (unwittingly) guards the only route through to the Throne Room where the Vemora is kept. If only Shirek knew about that teleportation arch. Let's hope no one tells him! Belisma Mort's ill-fated Company The Keep is strewn with the corpses of an unlucky band of adventurers who entered the dungeon a few weeks ago. This was the party of Belisma Mort, a Dunnar enchanter. They spent some days exploring the dungeon but bit off more than they could chew when they descended to the second level. They found the silver key in Captain Voln's quarters, but lost it when their Dwarf was captured by the giant spiders. Belisma was blinded when they disturbed the Cavasha and they fled back to the infirmary where they discovered another companion, Sezzerin, had contracted the Red Rot. One by one the adventurers succumbed to the Rot and reanimated as Plague Zombies, leaving Belisma as the last survivor, starving, blind and mad with fever, holed up in a remote guard post. This provides a bit of character for the anonymous corpses and the threat that, one by one, they will reanimate as Plague Zombies. If Belisma can be rescued, she will parley her map and information about the silver key for escort out of the dungeon - but this will put the party into conflict with Jacca Brone. Jacca Brone, the Dingleman Instead of being a pointless priest of Shalmar, Jacca Brone is beefed up to be the Dingleman overseeing Thornburg Keep. After all, this is a royal residence that holds a royal heirloom; moreover, it's a quarantine site that might still harbour a deadly infection. Jacca's job is to prevent greedy treasure-seekers (like Belisma Mort's hapless crew) breaking into the Keep. I've redesigned Jacca as a competent Beast Mage whose spells make him very effective at detecting intruders and negotiating the perils of the dungeon. He now features on the Wandering Monster table for the first level of the dungeon, which he patrols (looking for Shirek, whom he observed entering the site). Jacca's presence creates very different outcomes depending on whether the PCs are chartered adventurers in the service of the local King (unlikely) or trespassing treasure seekers doing an illicit favour for the local peasants (more likely). If the latter, then Jacca will turn the party away at the Keep's entrance: they need to sneak back later while Jacca is off patrolling and avoid him at all costs if they meet him in the dungeon. Yes, they could attack and kill him, but he's a royal officer so that's a crime that carries a capital punishment for all concerned. If the party can find a way to parley with Jacca (especially as the threat of the Red Rot grows), he has lots of information about the dungeon layout, the three keys, Shirek's incursion and the Cavasha. Of course, he won't let infected people leave the site - but he ends up becoming infected himself, as you will see. The Events that tell the tale Every time a Wandering Monster is indicated (10% chance, every hour), then next Dungeon Event occurs from the sequence of ten. These include things like Belisma's last companion dying and reanimating, Belisma dying, Shirek moving around the site, Plague Zombies animating and all the Giant Rats in the site becoming infected too. Among these Events, Jacca Brone becomes infected, which might well alter his negotiating position. This creates a linear narrative, as the plague spreads across the dungeon, infected corpses rise as zombies and the humanoids assemble to do battle with the Cavasha. There are now lots of opportunities for players to ally with or exploit the different factions - or just creep through the dungeon trying to avoid the mayhem. There's another collect-the-set mission, since the Master Healer's ledger now contains a cure for the Red Rot, which (naturally) involves the Cavasha's eyeballs. Reflections I'm very fond of The Vemora as a tutorial dungeon, but there isn't a great need for such a thing among my players. The Expanded Vemora upgrades the scenario into something more complex and dangerous that experienced players will enjoy. The Plague Zombies also replace quite a few of the tedious blood-drinking bats and acid-spitting crabs that pose pointless threats in the original. I'm a big fan of dungeons with a timetable of events: things that will occur in a certain order, with NPCs and monsters moving around, dying, capturing treasures, etc. This makes for a dynamic dungeon where adversaries do not simply sit in their rooms, waiting for PC adventurers to turn up and fight them. It also means that, if the players go away then come back again, the dungeon will have changed in their absence. The Red Rot makes a nasty adversary in its own right, creating drama as the players start showing symptoms. There is a chance that tough PCs on full Hit Points might survive the illness, but for most this introduces a terrible urgency to the exploration of the dungeon. Galignen as the background villain links the events in the scenario to Forge's intriguing mythology. As last-god-standing, Galignen hopes to make the last and decisive move in the God-Wars and claim the entire world for himself. The need to locate and secure the other Vemoras and perhaps take the fight to Galignen's Cult and the demi-god himself is a worthy plot for an epic campaign.