|

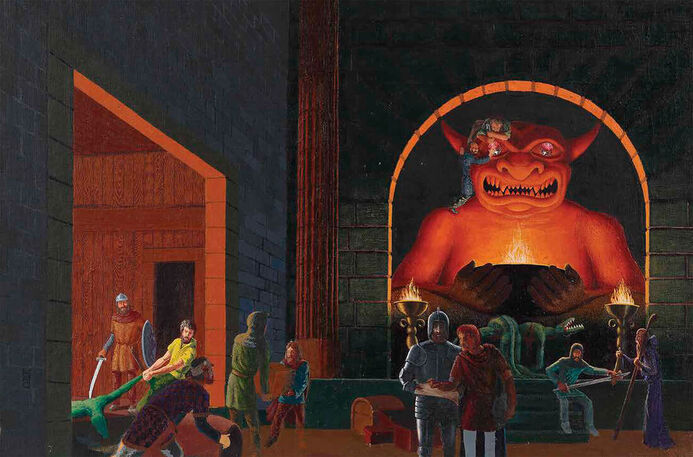

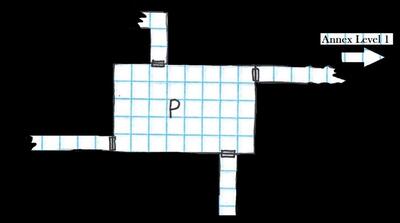

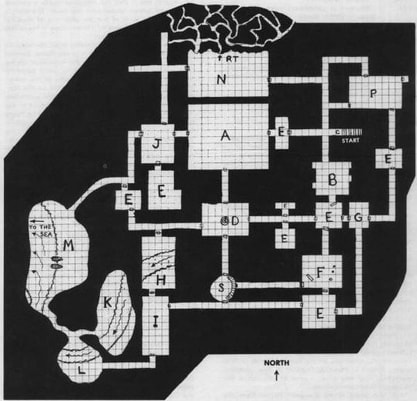

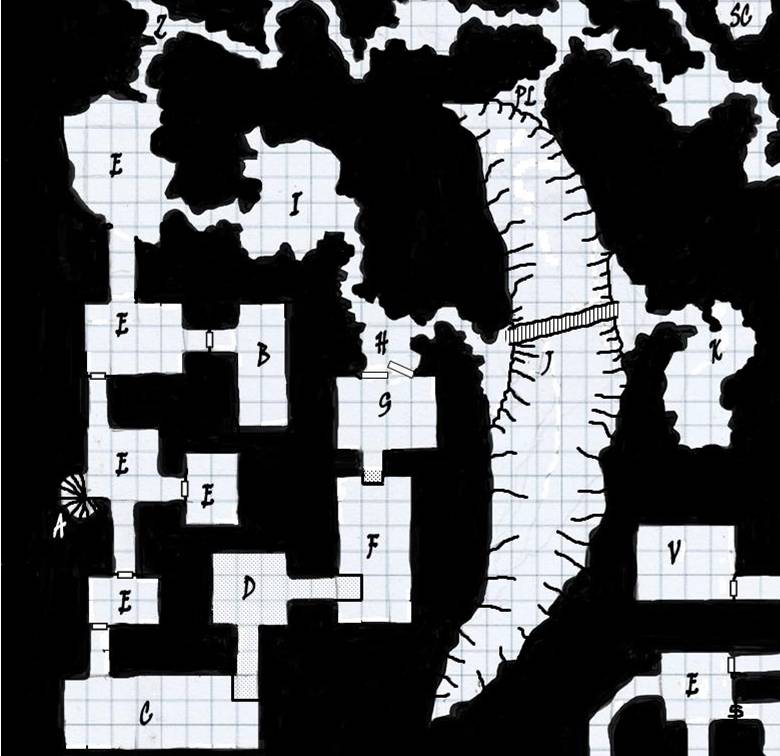

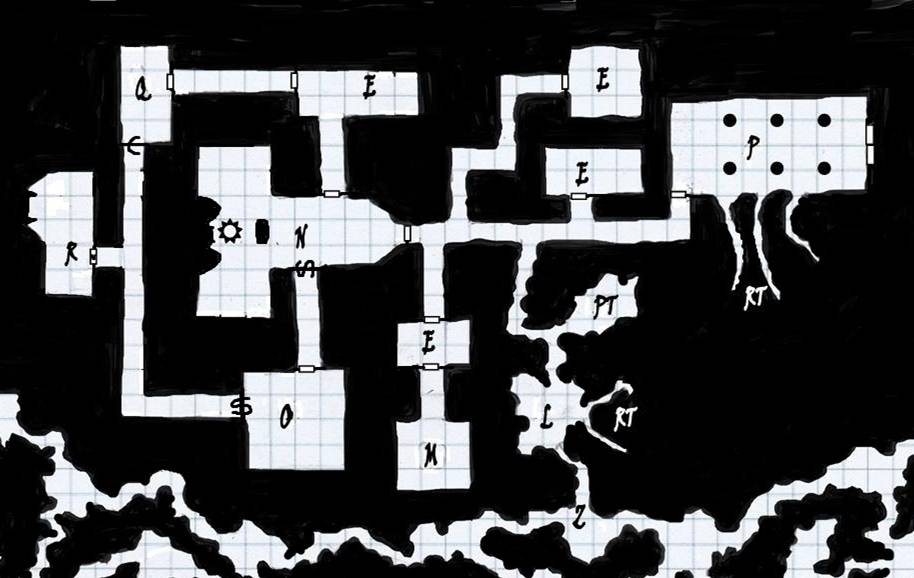

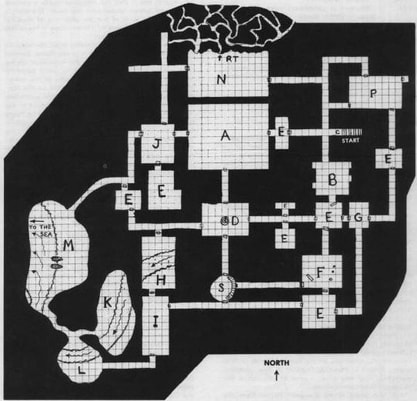

Zenopus is so hot right now. On the back of Zach Howard's well-received 5th edition reimagining of J. Eric Holmes' classic sample dungeon, The Ruined Tower of Zenopus, here's Clovis Kell with Return of Zenopus: The Lower Dungeons, available as PDF from DMs Guild. You can read my review of Ruined Tower of Zenopus or my retrospective of Holmes' 1977 classic dungeon on this site. First of all: full disclosure. I've got my own Zenopus sequel (Beneath the Ruined Wizard's Tower) over on drivethrurpg, but mine is for Blueholme/WhiteBox. I'll review Return of Zenopus as a D&D 5e scenario in comparison with Zach's 5e version of the original, not as a contrast with my own retro effort. What's it all about? Although Return of Zenopus is pitched as a sort of sequel, with the appearance of strange monsters around Portown suggesting to the worried authorities that the old wizard has returned, it doesn't need to play that way. Kell's dungeon works fine as a simple extension of the Zenopus dungeon and adventurers who cut their teeth on the celebrated first level can move seamlessly into these new levels without any particular hook needed. Return of Zenopus offers a brief discussion of how these new areas relate to Holmes' original map. First of all, there's a Dungeon Annex which is located off to the east of the site. This is an area that Holmes' formerly described as a tunnel ending in the cemetery. Zach Howard developed this footnote into a tunnel connecting to a chamber where cultists were creating undead. Kell turns this into a two-level 'mini-dungeon' that fleshes out his Zenopus backstory and should contrive to promote PCs to level 2 or even 3 once they complete it. Then there are two lower dungeon levels underneath the original site. Kell creates a secret door in Room N to allow access to these. The threats down here will put second level PCs to the test and the rewards should promote them to 3rd or 4th level. What's Zenopus up to? Kell makes the brave choice of outlining the real history of Zenopus and the reason for his disappearance. Of course, D&D players have been speculating about this for decades. Most gamers, on their first introduction to the Zenopus dungeon, will imagine that old Zenopus found some demonic idol, started worshiping it, opened a gateway to Hell and obliterated himself and his staff. And indeed, this is the explanation Kell goes for. So, no bonus points for surprise but at least newbie players get exactly what they expect from this dungeon. One nice touch is that the massive idol of Moloch discovered by Zenopus has "huge red quartz gemstones set in the eye sockets." I love this sly nod to David A. Trampier's iconic cover to the 1e Players Handbook. Tee-hee. Kell writes: "The vast majority of other statues of the era, are missing the gemstones, long ago taken by thieves and temple looters." The Moloch idol drives Zenopus mad in the prescribed fashion (memory loss, growing obsession with invoking Moloch) and, when he finally completes his rite, the hellfire from the portal blows everybody up. Half a century later, the lizardfolk and some human cultists are back to worshiping the Moloch idol, but down in the lower dungeons Zenopus lingers on as a demented wraith. Enter, the player characters... The Dungeon Annex This is a two level mini-dungeon, linked to the main site by a 300ft tunnel that links to Room P, the room in Holmes' dungeon that featured a couple of ghouls and "a short dirt tunnel which ends blindly under the cemetery." The first level of the Annex has stairs up to the Portown Cemetery (albeit to a crypt with a padlock on the gate) and various rooms housing anonymous Cultists and the Undead (mostly Ghouls) they have raised. What's well done here is the task of finding the key to the gate down to the second level and the advantage in sparing the Cultist leader who can reveal it. The second level contains more crypts that give way to caverns and a 7 mile tunnel that exits in the marshes off to the west. The Cultists here are bolstered by Lizardfolk but the iconic Moloch Idol is easy to find and PCs can enjoy themselves prizing out those massive gems from the eye sockets, just like Trampier drew it. There's a NPC prisoner to rescue from the sacrificial slab (the obligatory Elven maid) but the nasty trolls teased in the backstory don't make an appearance. Critique This is a perfectly decent mini-dungeon annex for the Zenopus site, expanding the role of the cultists and their undead goons. The Trampier idol is a nice touch. The layout is thoughtful and PCs who scout ahead or interrogate prisoners will be rewarded with tactical advantage. The factions at work here are linked to the Ghosts of Saltmarsh campaign - a link proposed by Zach Howard that works well here. On the other hand, there's a lack of dynamic purpose. The Cultists are just Bad Guys and their agenda is Undefined Villainy. It's not clear what they're doing down here, what their plans for Portown are, or what they want from Moloch. Even Selzelia the Elf Maid has hardly any hooks: she gets a detailed personal history but Holmes' female prisoner, Lemunda the Lovely, offered more story potential, as the daughter of a powerful lord in Portown. Selzelia might be a useful ally against the Sahuagin if you plan on following up with Saltmarsh but, as with the hints that the Lizardfolk and Cultist factions could fall out, no clear details are offered about this. The Lower Levels Directly beneath the dungeon mapped out by Holmes, Kell proposes two more levels that are "laboratories" created by Zenopus and now haunted by his Wraith. The entrance is a secret door added to Holmes' Crypt (Room N). The first level takes the party on a linear route, culminating at the lab where Zenopus blew himself up. Hopefully the PCs can fend off the Undead and realise that an innocuous gold coin has future significance. A hidden room beyond reintroduces one of Holmes' most memorable motifs, the talking Brazen Head. This one is rather more prosaic than the mystical oracle in the original: it just has a magic mouth spell on it and can be manipulated to reveal the stairs down. Downstairs are just two rooms. One has a pair of elegant (but rather easy) riddles that direct players to open a secret door. Beyond is Zenopus, now an angry Wraith, and a big fight for his treasure hoard. Critique These two levels only account for nine rooms, so anyone hoping the lower levels of the dungeon would be significantly expanded will be disappointed. They are also rather linear, unlike the much more interesting layout of the Annex which rewarded players who used scouting to understand their whereabouts. As with the Annex, it's a fairly routine slog through mechanical traps and unintelligent monsters (oozes, slimes, grumpy animals, undead). The design leans too heavily on things that damage or kill, which tends to discourage investigation. Players will not feel their curiosity is being rewarded but have no choice but to tamper with things if they want to make progress. Zenopus is a tough Big Bad, but he's also a disappointment. Partly because, this is Zenopus, yet all he does is rush up to players and start battering them. He has no spells. He's no longer a dreaded enchanter. He's just an undead bozo. Even by the standard of undead bozos, he falls short. In 5th edition, Wraiths are supposed to be undead warlords who command Spectres and have Wights as their shock troops. OK, there are 3 Spectres on the upper level, but there's no sense here that Zenopus is marshaling an undead army in pursuit of a diabolical master plan. He's just standing around, being a Final Boss. To be fair, Clovis Kell does urge DMs to make more of Zenopus: "This dungeon is not meant to be static, the wraith, Zenopus can be encountered in any area the DM deems appropriate. It would be interesting for Zenopus to encounter the PCs in several short scenarios before the final big battle." The thing is, we really need these interventions written into the structure of the dungeon, rather than left to creative DMs to ad lib. But more of this below. In conclusion: any good? Yeah, it's decent. It's not amazing, but it's solid. The question is, is that good enough? You're paying $2.99 for about 20 pages of material. The maps are hand drawn, but perfectly clear and in line aesthetically with Holmes' famous map from the D&D Basic Set (1977). Layout is consistent. There's some scrappy formatting, a few passages that need correcting, it's not up to the standard of Zach Howard's Ruined Tower but it's clear enough to digest and use. Some of Holmes' familiar tropes are acknowledged: the Brazen Head, the Catacombs and Cemetery, Zenopus' laboratory, the mandatory female NPC to be rescued. However, others are missing. Holmes follows Gygax's early advice that a third of rooms be empty, to allow players space to explore. He offers players things to investigate that are intriguing or wondrous or simply odd. He uses traps that confuse or inconvenience rather than damage or kill. He strikes a dreamlike tone that's part Dunsany-faerie, part-Lovecraft, part Errol Flynn swashbuckling and he's willing to invent monsters and unusual situations in pursuit of this (being swept away by a river, a giant octopus, a conjuror who runs away, an ape in a cage). In place of this, Clovis Kell offers a densely packed dungeon that threatens life and limb but rarely excites curiosity or wonderment. If you are a starting group of D&Ders, or perhaps an experienced DM with a party of rookie players, then the classic Zenopus dungeon is a great place to begin, Zach Howard's 5e iteration of it the obvious jumping off point, and Return of Zenopus positions itself to be a direct continuation of that story. Players might notice the shift from exploration to hackn'slash or might not; a good DM will pick up on the hints about NPC factions and deploy Zenopus to better, eerie effect; an inexperienced DM will struggle to offer more than a succession of monsters to kill. So my advice is, if you're running Ruined Tower for 5e D&D, you could happily follow on with Return of Zenopus, but the DM will need to do some unassisted work on fleshing out the Cultists and giving Zenopus a wider purpose and loftier presence. If you're an experienced D&Der, you'll be looking for something different from this module: a contribution to Holmes' lore, a development of the Tragedy of Zenopus, some ideas about the ultimate fate of the infamous wizard and an imaginative context to place Holmes' original dungeon in. From this perspective, Return of Zenopus falls flat, offering only the most conventional backstory of arrogant-wizard-gone-bad and diminishing the numinous figure of Zenopus into another anonymous dungeon-dweller, to fall beneath the PCs' enchanted blades. Artistically, there's a missed opportunity here to do something memorable with the fate of Zenopus. The Annex and Lower Levels fail to capture the atmosphere and playstyle of the original - although that might be due to the centrality of combat in what constitutes a typical 'dungeon adventure' in 5th edition compared to old school Basic D&D.

0 Comments

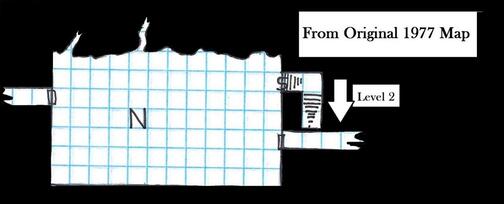

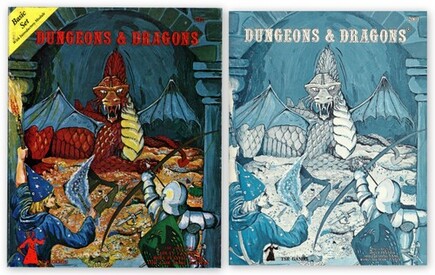

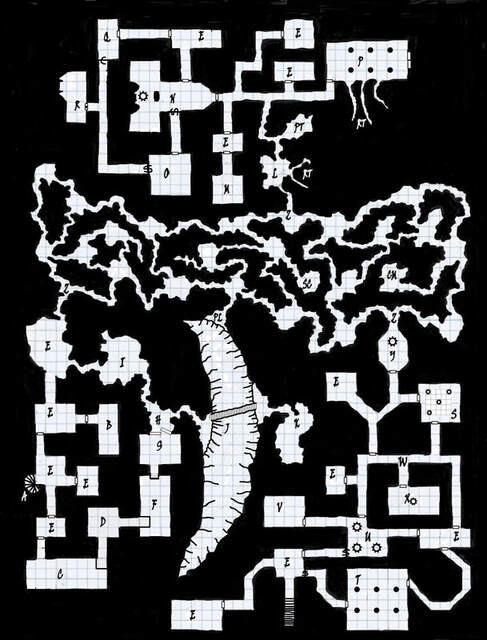

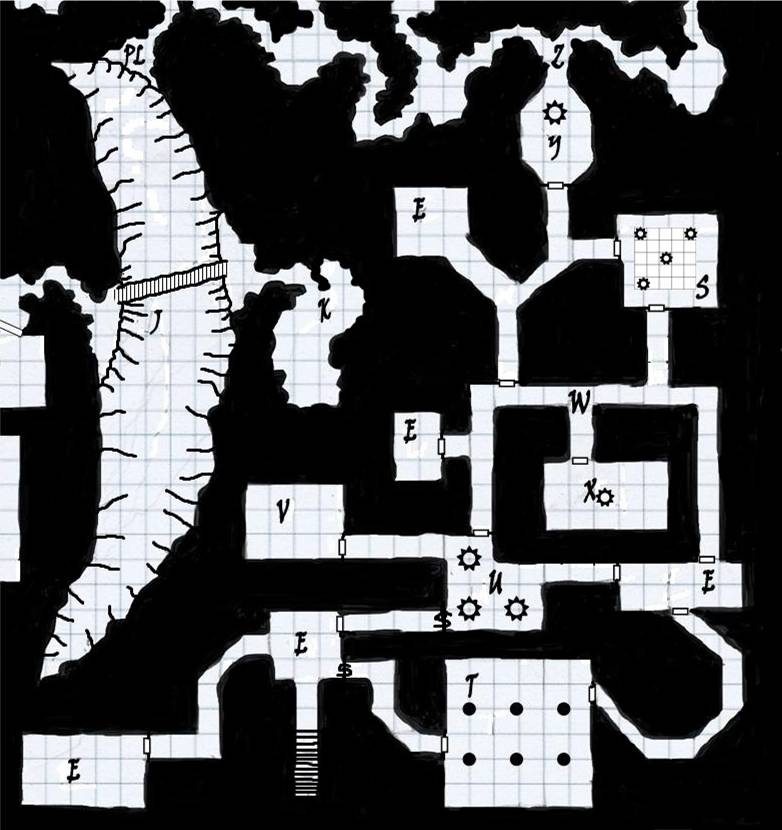

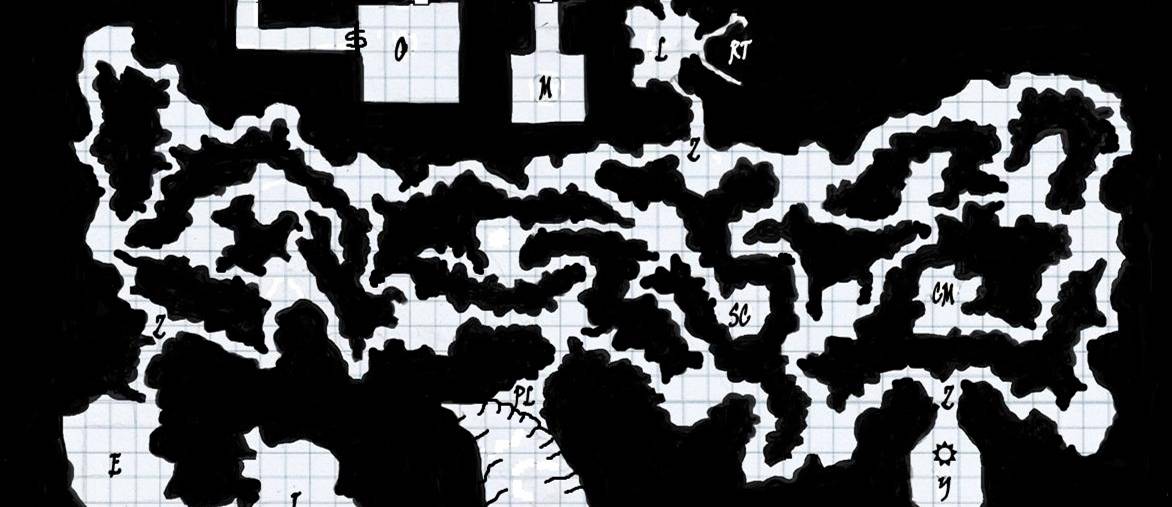

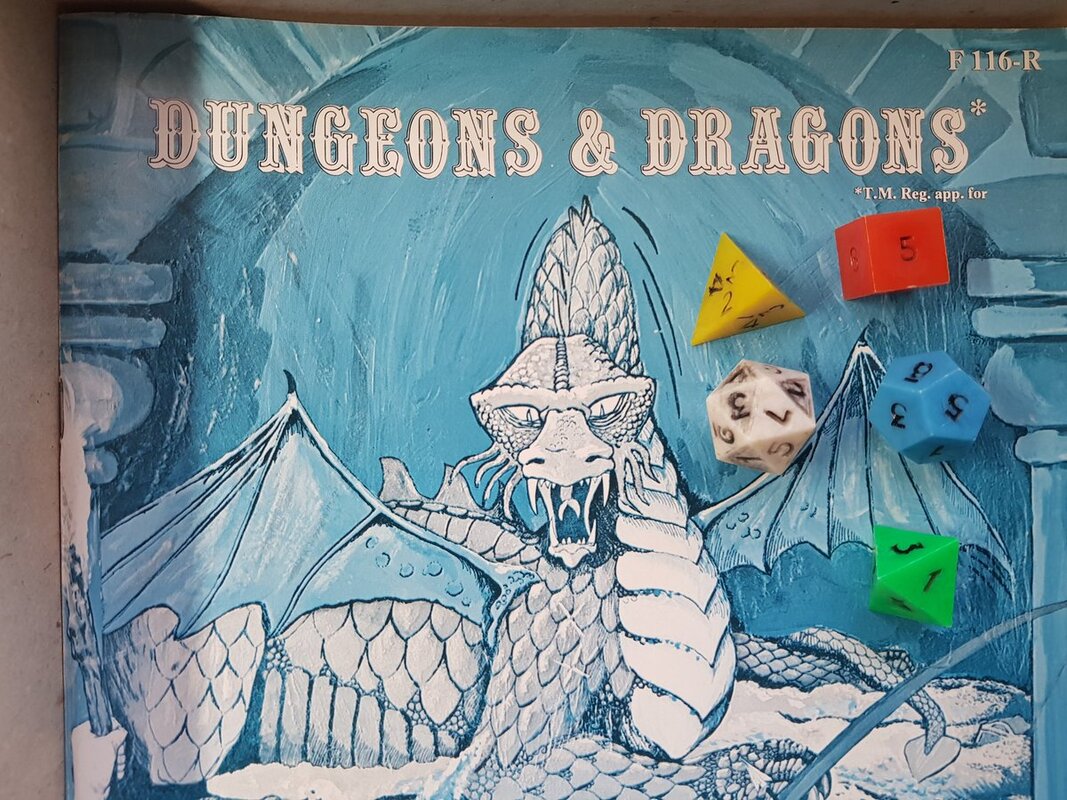

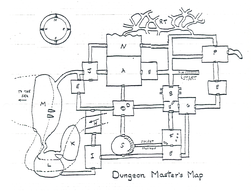

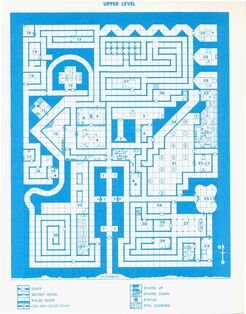

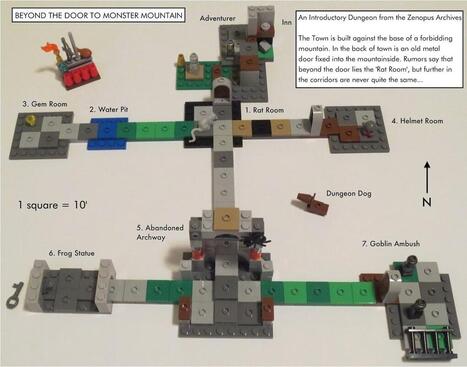

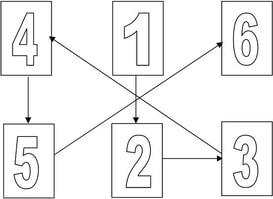

It was October half term in 1978 and I was 11 when my best friend Simon introduced me to the two-tone record label and Dungeons & Dragons. I never really got into ska music but the other thing had a mighty effect on me. After that fateful weekend, nothing would do but my parents must buy me my own Dungeons & Dragons set for Christmas. What I unpacked with feverish fingers was J. Eric Holmes' D&D Basic Set, AKA the 'Blue Box'. And so it was that my baffled family were forced to create characters and explore the Sample Dungeon therein, the tunnels beneath the ruined Tower of Zenopus. I've written about the classic Sample Dungeon on a previous blog and reviewed Zach Howard's authoritative adaptation for 5th ed. D&D as well. Now my daughter Emily is refereeing the 'Zenopus Dungeon' on her own friends. The time is right to realise a dream that is 40 years in the making... to design the second level to the fabled Holmes Sample Dungeon! It's pay-nothing on drivethrurpg. The title alludes to Eric Holmes' introduction to his dungeon: "At the Green Dragon Inn, the players of the game gather their characters for an assault on the fabulous passages beneath the ruined Wizard's tower" Of course, Holmes intends exactly this response from readers and fans: go design your own levels to this dungeon! By the time the adventurers have worked their way through this, the Dungeon Master will probably have lots of ideas of his or her own to try out. Design your own dungeon or dig new passages and levels in this one. What lies in the (undiscovered) deeper levels where Zenopus met his doom? The artwork to this set, by David C Sutherland III, probably defines my childhood more than any other artifact except this tattered old copy of The Mighty World of Marvel from 1974! So I'm offering this dungeon design up, partly as a gift to my daughter, but in no less part to my 11-year-old self, who had (I now know) more wisdom and depth to his thought and feeling than the 15, 25 and indeed 45 year old versions that followed. Analysing Homes' craftsmanship I've seen a few very careless reviews of the Holmes Basic Set that dismiss the sample dungeon with an indulgent chuckle: it's a 'zoo dungeon' with 'no rhyme or reason to it' and has its iconic status by virtue of its placement in this best-selling set rather than its own virtues. This is, I believe, deeply mistaken. Let's look at what Holmes does. Holmes' introduction to the dungeon links it to the mysterious fate of the wizard Zenopus, who created a Tower overlooking Portown, near to the sea, neighbouring the graveyard and above the ruins of an older, pre-human city. This triptych - the pre-human city, the graveyard, the sea - rings through the dungeon like the tolling of a bell. The sea hints at the wider geography of Holmes' world, where rascally pirates kidnap beautiful noblewomen for ransom and hide them in sea caves where they are menaced by giant crabs; this is the world of adventure romance of H. Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The pre-human city alludes the fiction of Robert E Howard and H.P. Lovecraft and the like, with their horror-inflected influence on fantasy. And the graveyard speaks for itself: horror served up straight, with a tincture of existential mystery: the "undiscover'd country" as Hamlet says, "from whose bourn no traveler returns." His dungeon bears out this promise. To the west, the pirates and smugglers hold Lemunda the Lovely prisoner. To the south, a mad Thaumaturgist holds prisoners enchanted, masks speak, doors lock and a tower is guarded by a giant serpent - straight out of a Conan story. To the north, the criss-crossing corridors lead explorers into crypts haunted by ghouls, occupy them in breaking into crumbling sarcophagi in search of wealth, magic and curses and all the while fighting off the ravening giant rats that erupt from their tunnels. There is one entrance but multiple exists. Explorers can find themselves rowing out of the caves into "the pirate-infested waters of the Northern Sea", digging their way through the maggoty earth into the cemetery or emerging, blinking, into the workaday streets of Portown from the Thaumaturgist's Tower. Then there are the endless Rat Tunnels, disappearing into "the catacombs of the city." Delta's D&D Hotspot has produced an excellent mathematical analysis of the Sample Dungeon: 23 rooms, with 8 empty (35%); a total of 4650gp to be garnered, including 5 magical items, and, if every monster is defeated, 940xp to be earned in battle. This is nice but not fulsome. If four 1st level characters cleared out the dungeon, only the Thieves and perhaps the Clerics would reach 2nd level. However, if we compare this to Gary Gygax's advice on dungeon design, Holmes' dungeon looks quite generous: As a guideline, it should take a group of players from 6 to 12 adventures before any of their characters are able to gain sufficient experience for successive levels The Holmes Sample Dungeon shouldn't take more than 3 or 4 raids to complete. Holmes' original manuscript seems to be a bit different, with a mere 413xp from killing monsters but a whopping 17,555gp in treasure - enough to promote most 1st level characters all the way to 3rd level. The version we use is a synergy of Holmes' creativity and Gary Gygax editing. What's on the Second Level? (and SPOILERS) Here's my map for the second level. I'd love to claim its shaky, hand-drawn quality is an homage to Holmes' original, but in truth its a concession to necessity: I couldn't draw a slick professional dungeon map if I wanted to! Nonetheless, it looks nice and 1977-ish. Perhaps a bit lacking in Holmsian long corridors going nowhere, but I wanted it to fit on a page. I've taken the dungeon level up to 40 rooms, of which 13 are empty, preserving Holmsian proportions, but increasing the overall size by just under 75%. There's a mixture of rooms and caves. The rooms are mostly Holmsian oblongs but I've got a couple of Gygaxian polygons and diagonal corridors in there too. I've retained and tried to develop Holmes' three themes by region:

One feature I've taken from Zach Howard's 5th ed. conversion of the Holmes Sample Dungeon is "Optional" text boxes, to allow less experienced Referees to introduce complexity as and when they feel comfortable. These options enable players to sneak past the wights by pretending to be undead (in the style of Shaun of the Dead) and the revelation that the Undead Corsair's faithless wife was the identical double of Lemunda the Lovely. So that's why the Smugglers kidnapped her! Wily or desperate players might parlay with the Corsair to reunite him with his bride!

David Trampier's iconic cover art and Will McLean's witty pastiche from the 1979 Dungeon Masters Guide The prisoners subvert the stereotypes, much as the action-ready Lemunda did on the first level: one is a traitor, another doesn't want to be rescued. A magic mirror reconnects the dungeon to a town house in Portown, just like the Thaumaturgist's Tower, and I propose an evil secret society in Portown itself, connecting the Rat Cult to the Thaumaturgist. Finally, there are options to negotiate with or avoid monsters, just like the Goblin Barracks in Holmes' Sample Dungeon.

The new monsters here are Crystal Spiders whose poison petrifies - or rather, crystal-ifies - victims. Nasty, but astute players might find a cure in Zenopus' laboratory.

Brief Analysis An inventory of the dungeon shows a treasure haul of 7750gp and 2010xp from battling monsters. Of course, second level monsters are worth more XP or else are present in greater numbers. The total value of the dungeon is about 75% greater than Holmes' first level; in other words, it preserves the same reward-per-room ratio. You might say, Shouldn't it offer more reward-per-room than the first level? I scratched my head over this. Second level adventurers require the same XP to get to 3rd level as it took 1st level adventurers to hit 2nd level. So, if you want your players to progress at a constant rate, the second level needs to offer rewards on a comparable scale to the first level or else everyone races up to third level of experience too quickly. Of course the second level is bigger so players will advance further, but they will have to work for it... There are plenty of grand treasures on this level and some nice magic (especially in Zenopus' lab which could be used to produce potions and enchant swords) but the overall content is sufficient to get most characters who completed the first level beforehand up to 3rd level by the time this level is completed - except perhaps for slowpoke Magic-Users and those Elves, but you knew what you were in for when you created that Elven fighter-magic-user, right? That only leaves the third level in order to complete the "Holmes Basic Progression" up to 3rd level for everyone - and beyond, for those speedy Thieves and Clerics. What's at the bottom of that Chasm? What's beyond the Gates to the City Catacombs? Where does the teleportation Portal lead? Where, indeed? Post Script: Conversions The dungeon is written for Holmes Basic Set, which means it also works for the Blueholme retroclone. Nothing needs to be done to convert to Moldvay Basic or Mentzer Basic or retroclones like Basic Fantasy, Dark Dungeons, OSE or Labyrinth Lord. If you use AD&D or retroclones like OSRIC, you might need to compensate for tougher adventurers with more Hit Points and spells: the Undead Corsair should be a Wraith, the Master Ghoul a Ghast, the Wererats should be a 3rd level Cleric (Lowill Dreb) or Assassin (Kara the Winsome) and the Living Crystal Statues should be half-strength Stone Golems (+1 weapons to hit, 30 Hit Points, 3d6 damage, cast Slow once per combat). Heading in the other direction, if you use OD&D or a retroclone like White Box or Delving Deeper, you need to adapt for monsters that only deal 1d6 damage and have d6s for Hit Points. The Brine Zombies should have 1+1 Hit Dice; the Ghouls only get a single attack for 1d6 plus paralysation, but the Master Ghoul should attack for 1d6+1 and impose a -2 penalty on saving throws; the Living Crystal Statues should get a single attack for 1d6+2. If you use my house rules for Death & Dismemberment or Trauma & Derangement, then the Lethality Die for this dungeon is 1d6. Entering each region for the first time imposes 1 Trauma and adventurers lost in the Crystal Labyrinth gain 1 Trauma per hour unless they stop wandering; crossing the Perilous Chasm is worth 1 Trauma for non-Thieves as is slipping and dangling from the bridge. Experimenting in the Wizard's Laboratory is worth 1 Trauma at each bench for non-Magic-Users.

Shakespeare knew a thing or two. In The Tempest, the lovers Ferdinand and Miranda are discovered playing chess: an image of harmony as they engage in play-conflict, while around them the real conflict on the island is harmonised by the putting on of a play. Then Miranda, rising from her toy soldiers, sees real soldiers for the first time and exclaims: "O brave new world that has such people in it!" After a couple of weeks of isolation, you get a sense of Miranda's delight in human contact. Have you ever been so involved in a game, you forget there were real people out there, playing it with you? But much worse is when you look around and all the real people have all disappeared and you're just surrounded by chess sets! Wait a moment: THAT'S not Ferdinand and Miranda! The business of reconnecting with people through play is on my mind. Which is to say, yes: I've been trying to get round the current crisis by doing roleplaying online. Online roleplaying. It’s a substitute isn’t it? Like nicotine gum or aspartame. What you want is to be round a big table with your friends, rattling dice, scribbling notes, cracking jokes, putting on voices, gesticulating, pausing for outbursts of hysterical laughter. What you get is a bunch of people squinting at their webcams saying things like “Is this ON?” and “I can’t HEAR you!” and “Can anyone hear ME?” and “Where did Rob go?” My gaming group and I, we are getting round the ‘Rona by meeting in Google Hangouts to enjoy fun, regressive D&D. I haven’t taken D&D seriously in an age but it lends itself to this new medium because (i) everyone knows what they’re doing in a dungeon and (ii) dungeons impose their own rhythm and discipline which you can lean into pretty hard while people are trying to get their webcams to work. The medium has actually brought together old faces and new faces: veteran gaming buddies and new ones, people I’ve never gamed with before, even my daughters. Online interaction might be awkward but it has expanded our circle and broadened our social world. I suppose, like a lot of ‘Rona coping mechanisms, it disrupts our old patterns and networks, causing us to reform them in new and interesting ways. Now THAT'S Ferdinand and Miranda I think about The Tempest a lot, because it seems to be about the power of creativity and play to unite people under difficult circumstances. Prospero and Miranda are isolated on their island and Ariel's magic ensures the shipwrecked protagonists are socially distanced. Yet they are nonetheless brought together and reconciled; they see each other with fresh eyes thanks to Prospero's masque: the art of a Dungeon Master. Welcome to the White Box Back to D&D. Or rather, WHITE BOX RPG. You see, the question of ‘What version of D&D do we play online?’ is a vexed one. Tactical movement is out since I can’t cope with the psychic overload that is Rolld20. It’s theatre of the mind all the way for me. I’m too set in my ways to master 5th edition. Heck, I’m too set in my ways for 3rd edition. So it has to be loosey-goosey fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants D&D. That means Old School D&D. The Oldest of Schools. Charlie Mason produced White Box RPG as a 2017 update of Swords & Wizardry: White Box (2009), which is Matthew J Finch’s ground breaking retro-clone of the original Gygax/Arneson D&D ruleset from 1974-8 (known to fans as the ‘White Box’ set – hence the name). Mason's White Box is a sweet little 144 page softback with fantastic B&W art in that heavy, baroque 1970s/80s style. You can pay (not very much) for a nice copy or just download the PDF for free. What you get is D&D stripped down to its undies and cranked up on Jack Daniels. Everyone gets six sided Hit Dice. All the weapons do a single d6 damage, +1 or -1, and all the monsters do 1d6 damage, except dragons etc (they do 2d6 damage). Time that you’re not wasting consulting tables or navigating stat blocks is time that you are spending on vivid description or fiendish creativity. Or getting your webcam to work. Either way, it’s liberating. White Box has some 21st century touches. It offers the Ascending Armour Class system as an option and I fully endorse that: AC becomes the number you need to roll on a d20 to hit your opponent and everyone gets to add their Hit Dice to the roll. I’ll review White Box in more depth in another post: suffice to say, I’m thoroughly enamoured. I can provide my players with little PDF copies and they – coming from a range of backgrounds, ages and differing experience with RPGs – all grasp these mechanics instantly, with veterans having no real advantage over newcomers. Welcome to the Dungeon We have a group of players, consisting middle aged men, young thrusters in their 20s, my crazy daughters, a motley crew and most have them have never roleplayed with each other before or with me DMing before. It’s going to be important to choose the right scenario. So I chose the wrong scenario. Let me be clear: there’s nothing wrong with Dread Crypt of Skogenby. It’s a crackin’ scenario for TORCHBEARER RPG and it converts to D&D easily: I’ve got a blog post discussing it. Click the image to visit the PDF Yes, it's a crackin' adventure but it is quite a demanding one. It’s also a one-shot that funnels the players into a tense showdown with a powerful spirit. I know that, ordinarily, my round-the-table players would gobble this scenario up. They would delight in figuring out its evocative mythology, they would engage with the spirit in a theatrical way, they would find some clever-sensitive way of laying it to rest and/or retreating with the young girl they’d been sent in to rescue. In the online version of things, not so much. The unholy trinity of mic/webcam/text is a bit alienating anyway and can make strangers of people that we feel we know so well when they’re sat across from us in person. Add to that the problem that some of these people really don’t know each other all that well and you have a communication problem. Again, round the table there’s often nothing else to do but speak up. But if you’re at home, in front of your screen, dealing with people remotely, the temptation is to let others do the heavy lifting. I think I was less forceful and directing as a DM; the players were less communicative and mutually supportive, less curious. Anyway, it was a Total Party Kill. They all died. Thank you folks and good night. See you next week, I hope…! Welcome to the Mega Dungeon You see, a bunch of new (to each other) players tentatively exploring RPGs in a new medium don’t want a tight, demanding one-shot scenario. They need something a bit more generous; something that gives them space to wander and time to get onto each other’s wavelengths, master the technology, find a rhythm, grow some confidence. What they need is a great big wibbly-wobbly dungeon with lots of empty rooms and long corridors, traps and puzzles, rooms to inspect and then not go into, wandering monsters and big piles of treasure. They need to be able to go where they want and stop when they want, without being shepherded into a scary climax or forced to confront something nasty. They need a sandbox to play in. They need a MEGADUNGEON! The discussion about what megadungeons are and what’s good or bad about them can wait for another blog post – but if you can’t wait that long, go and read this: The beauty of a megadungeon is that it’s huge, the entire campaign takes place inside it (more or less); you can wander in at 1st level and keep on adventuring till you wander out at goodness-knows-what-level. Bad megadungeons are all hack’n’slash but good ones have NPC interaction, politics and factioneering, mysteries and a sense of emergent epic plotting There are a lot of these on the market, so I questioned my sources on the Outer Planes and came up with two: STONEHELL: DOWN NIGHT-HAUNTED HALLS and BARROWMAZE COMPLETE. Click the images for links to lulu (Stonehell, also PDF version) and drivethrurpg (Barrowmaze) There’s a clear difference in the products. Greg Gillespie’s Barrowmaze was crowdfunded and has top notch production values: striking old-school art (some of it by TSR luminaries), wonderful graphic design and maps, the whole 260 pages are sumptuous. It’s also ambitious. It introduces you to a region, its history and religions, the vast Barrowmaze itself and the myriad micro-dungeons that sprout out of it like toadstools. It will take me a month to digest this and another month to dream about it. Then I’ll be ready to DM it. I reckon the ‘Rona will still be around by then. Michael Curtis’ Stonehell is a much more modest affair. It’s softback, 134 pages, 5 dungeon levels and 700 rooms (but more levels available separately). The art is minimal, the graphics are competent, but it’s crystal clear throughout and uses Bowman & Shorten’s 'One Page Dungeon' method. Each level is introduced with a few pages of discussion and spotlight on key monsters, NPCs and artifacts, then the level gets broken into 4 quadrants and each quadrant has its map and random tables on a single page and the room descriptions on the facing page. So easy to use. You can almost pick-up-and-play. Both dungeons are designed for use with Daniel Proctor’s LABYRINTH LORD, which is a popular retro-clone of the Moldvay/Cook Basic/Expert D&D rules from 1981, extended up to 20th level. Now Moldvay/Cook D&D is pretty much the Rosetta Stone of early Fantasy Roleplaying (before things started going all strange with cantrips, non-weapon proficiencies and healing surges), so if you can’t make Labyrinth Lord convert to your preferred OSR version of D&D then there’s something the matter with you. Stonehell it is, then We’re starting with Stonehell. Don’t worry: no spoilers. The players created their characters and this follows a now familiar trajectory: the characters are all a bit silly, but over the first few sessions they discover their own identity and become more serious and flavourful. Homebrew class variants and races pop up instantly: Darjeeling is a convicted Thief whose hand was chopped off. He has a mechanical socket there now into which he slots a range of attachments: grapples, cork screws, files, flints for lighting tinder, something for taking stones out of horses’ hooves, that sort of thing. ‘Swampy’ is a Swamp Elf, with a sort of Iroquois aesthetic. He served a tour with the Warden Rangers who gave him his nickname. He doesn’t share his true name with anyone until they’ve earned his loyalty and trust. He's good with poisons but his magic is slow. Horatio is a Street Mage with a newt familiar named Nelson. Street Mages have trouble with real magic but they’re great with smoke bombs, sleight of hand and chicanery: they can pick locks and wield short swords. Shame he only has 1 HP. Dian is a Danaan Druid, who has a wild boar heart-companion and wields spears and scimitars, but turns faeries instead of undead. Good luck with that! Along the way, we have to introduce a new PC, but since the gang are exploring a crypt, it makes sense for the character to be Gore, a Half-Ghoul who has spent a century locked in an ossuary, gradually evolving a rational mind. If you're intrigued, the file for these new variants is available below: it will work for any other early D&D variation (Holmes, Basic/Expert, etc).

We've run a couple of sessions. It’s a fitful process – and not just because of the Internet, which enables and impedes in equal measure, according to its whims. I’m used to creating a campaign with a lot of setting and clear plot arc in mind then getting players to create the sort of characters needed to tell that story. This experience reverses all that: the players roll dice and create whatever characters they see fit then charge off into Stonehell and out of this chaos something orderly emerges, somehow, perhaps. It’s a style of roleplaying I haven’t really explored since I was a teenager. I find myself strangely energised by all this. I'm buying better mics, a webcam that works, browsing gigantic dungeons, composing or stealing homebrew rules, anticipating the next session when the PCs might get to that room or fall into that trap. The news media brings its daily miseries as the 'Rona prowls around our houses, but here, for a while, playing these games, I feel removed from the present anxieties. I identify, I hope optimistically, with Shakespeare's Prospero as he brings his masque to a close: We are such stuff After reviewing Mark Kibbe's 1998 module, I set about expanding it in order to develop its dangling plot threads: what was the truth behind the deadly plague that brought down Thornburg Keep and resisted even the healing powers of the Vemora? what is Shirek the Ghantu doing in the Keep and what are his humanoid minions searching for? what happened to the Cavasha? how does all this fit into the Kibbes' mythology of banished gods? The expansion document is found on the SCENARIOS page. Paul Butler's lovely cover illustration of the Cavasha: alas, the scale of the houses is all wrong The Return of Galignen The Forge rulebook introduces Galignen as the god of Disease, but also of nasty plants (fungus, molds, slimes, etc). He's the younger brother of Necros (Death) and Grom (War) and joined their Triumvirate that tried to take over the world during the God-Wars. He is "deceitful and unscrupulous" and "despises mankind" which he looks upon as "insects" and he "twisted man into sentient flora." During the God-Wars he "unleashed pestilence and plagues, the most severe of which was known as the Rotting Death." Artist Mike Connelly's depiction of Galignen The rules list Galignen among 'Those Taken from Juravia' as opposed to Necros (cast into the Void) and Grom and Berethenu (banished to Mulkra/Hell). Why did Galignen get off so lightly, since he seems just as malevolent as Necros and as destructive as Grom? An idea for a Forge campaign could focus on Galignen: what if he escaped creator-god Enigwa's wrath and judgement by merging himself with Juravia's plantlife? For hundreds of years, Galignen has been present in Juravia, assumed to be banished but really just left behind. He has spent that time slowly recovering his sentience and a bare fraction of his divine power, perhaps inhabiting a giant fungus colony in a deep cavern, attended by a loyal cult. The secret of the Vemora There is more than one Vemora. The Vemoras are relics left behind by Enigwa in his wisdom to counteract the power of Galignen, should he have survived the God-Wars. The Vemoras' healing properties are side-effects of their true purpose: they are the spiritual locks that prevent Galignen returning in power. In order to regain his full divinity, Galignen needs to corrupt or destroy all of the Vemoras. The attack on Thornburg Keep's Vemora is just one manoeuvre in Galignan's plan, which has battles on many fronts. Galignen sent his own worshipers to Thornburg Keep, infected with the Red Rot, to close the healing sanctuary down. His next move is to retrieve the Vemora for himself. Unfortunately, the Red Rot drew on far more of the god's power than he calculated (and he was perhaps badly defeated in his attempt to retrieve another Vemora elsewhere). Galignen has spent 80 years recovering his power - but what is a century to a god? He is ready now to reach out and seize the Vemora. He has sent his worshiper Shirek the Ghantu to do this. When the Vemora is brought back to him, it will become Galignen's Chalice of Plagues, restoring a large measure of his power to create diseases. The Red Rot Galignen developed this plague in collaboration with his brother Necros. It is a hemorrhagic fever (rather like Ebola) which covers the poor victim in blood-seeping sores. Worse, the corpse of a victim is reanimated as a Plague Zombie. Galignen intended the Plague Zombies to overrun Thornburg Keep and bring the Vemora to him themselves. He was thwarted in this. The master Healer of Thornburg Keep was wise enough to burn the infected corpses and evacuate the Keep. Exhausted, Galignen allowed the plague to fall dormant. Now he's ready to try again, but this time he won't trust in zombies! Shirek and the Plague Cult Most of Galignen's cultists are sentient flora, but he has a few fleshy worshipers like Shirek and his Higmoni lieutenant Voork. The Higmoni's natural regenerative powers enable them to endure the Red Rot for far longer than other creatures: they believe that, if they are successful in their mission, Galignen will cure them, but they are surely mistaken in this. Shirek is a true acolyte of the cult and bears countless infections and fungal growths on his flesh, but Galignen's power makes him immune to them: he is the example of the god's power that inspires the Higmoni to put up with the infection they endure. However, should he succeed in his quest and bring back the Vemora, even Shirek will be abandoned to die or, at best, be transformed into a shambling plant. Shirek has set his minions to work ransacking the dungeon, looking for the three keys that unlock the Vemora, but has so far come up with nothing. Worse for him, the Cavasha has set up its lair in the Keep and (unwittingly) guards the only route through to the Throne Room where the Vemora is kept. If only Shirek knew about that teleportation arch. Let's hope no one tells him! Belisma Mort's ill-fated Company The Keep is strewn with the corpses of an unlucky band of adventurers who entered the dungeon a few weeks ago. This was the party of Belisma Mort, a Dunnar enchanter. They spent some days exploring the dungeon but bit off more than they could chew when they descended to the second level. They found the silver key in Captain Voln's quarters, but lost it when their Dwarf was captured by the giant spiders. Belisma was blinded when they disturbed the Cavasha and they fled back to the infirmary where they discovered another companion, Sezzerin, had contracted the Red Rot. One by one the adventurers succumbed to the Rot and reanimated as Plague Zombies, leaving Belisma as the last survivor, starving, blind and mad with fever, holed up in a remote guard post. This provides a bit of character for the anonymous corpses and the threat that, one by one, they will reanimate as Plague Zombies. If Belisma can be rescued, she will parley her map and information about the silver key for escort out of the dungeon - but this will put the party into conflict with Jacca Brone. Jacca Brone, the Dingleman Instead of being a pointless priest of Shalmar, Jacca Brone is beefed up to be the Dingleman overseeing Thornburg Keep. After all, this is a royal residence that holds a royal heirloom; moreover, it's a quarantine site that might still harbour a deadly infection. Jacca's job is to prevent greedy treasure-seekers (like Belisma Mort's hapless crew) breaking into the Keep. I've redesigned Jacca as a competent Beast Mage whose spells make him very effective at detecting intruders and negotiating the perils of the dungeon. He now features on the Wandering Monster table for the first level of the dungeon, which he patrols (looking for Shirek, whom he observed entering the site). Jacca's presence creates very different outcomes depending on whether the PCs are chartered adventurers in the service of the local King (unlikely) or trespassing treasure seekers doing an illicit favour for the local peasants (more likely). If the latter, then Jacca will turn the party away at the Keep's entrance: they need to sneak back later while Jacca is off patrolling and avoid him at all costs if they meet him in the dungeon. Yes, they could attack and kill him, but he's a royal officer so that's a crime that carries a capital punishment for all concerned. If the party can find a way to parley with Jacca (especially as the threat of the Red Rot grows), he has lots of information about the dungeon layout, the three keys, Shirek's incursion and the Cavasha. Of course, he won't let infected people leave the site - but he ends up becoming infected himself, as you will see. The Events that tell the tale Every time a Wandering Monster is indicated (10% chance, every hour), then next Dungeon Event occurs from the sequence of ten. These include things like Belisma's last companion dying and reanimating, Belisma dying, Shirek moving around the site, Plague Zombies animating and all the Giant Rats in the site becoming infected too. Among these Events, Jacca Brone becomes infected, which might well alter his negotiating position. This creates a linear narrative, as the plague spreads across the dungeon, infected corpses rise as zombies and the humanoids assemble to do battle with the Cavasha. There are now lots of opportunities for players to ally with or exploit the different factions - or just creep through the dungeon trying to avoid the mayhem. There's another collect-the-set mission, since the Master Healer's ledger now contains a cure for the Red Rot, which (naturally) involves the Cavasha's eyeballs. Reflections I'm very fond of The Vemora as a tutorial dungeon, but there isn't a great need for such a thing among my players. The Expanded Vemora upgrades the scenario into something more complex and dangerous that experienced players will enjoy. The Plague Zombies also replace quite a few of the tedious blood-drinking bats and acid-spitting crabs that pose pointless threats in the original. I'm a big fan of dungeons with a timetable of events: things that will occur in a certain order, with NPCs and monsters moving around, dying, capturing treasures, etc. This makes for a dynamic dungeon where adversaries do not simply sit in their rooms, waiting for PC adventurers to turn up and fight them. It also means that, if the players go away then come back again, the dungeon will have changed in their absence. The Red Rot makes a nasty adversary in its own right, creating drama as the players start showing symptoms. There is a chance that tough PCs on full Hit Points might survive the illness, but for most this introduces a terrible urgency to the exploration of the dungeon. Galignen as the background villain links the events in the scenario to Forge's intriguing mythology. As last-god-standing, Galignen hopes to make the last and decisive move in the God-Wars and claim the entire world for himself. The need to locate and secure the other Vemoras and perhaps take the fight to Galignen's Cult and the demi-god himself is a worthy plot for an epic campaign.

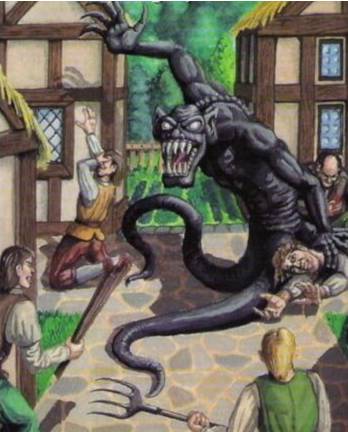

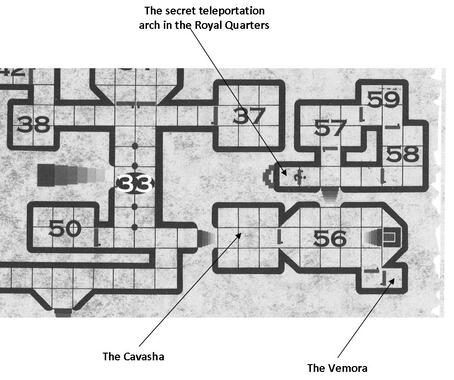

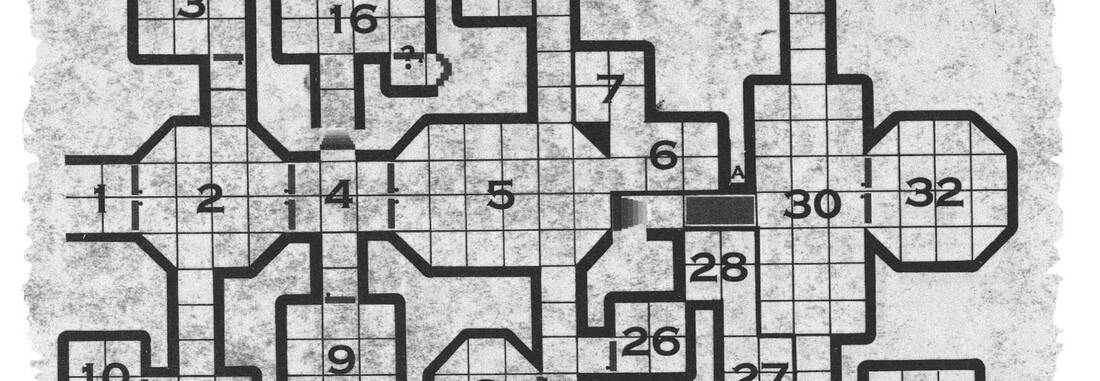

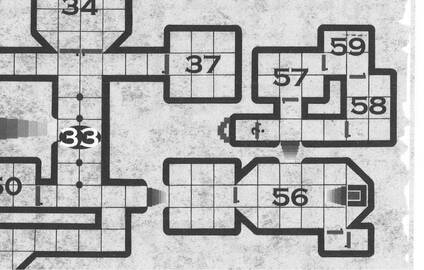

The Vemora is the first scenario published for Forge Out Of Chaos by Mark Kibbe back in 1998. It retailed back then for $7.98 and consists of a 28-page staple-bound book with colour cover art (by Paul Butler) and some B&W interior art (by Mike Connelly & Don Garvey who worked on the original rulebook), including two maps and lots of drawings of rooms and enemies discovered during the scenario. There's a detailed NPC and two new monsters (mutant animals, nothing special) and a small amount of information about the setting. For me, the product is interesting for what it reveals about the sort of game Mark Kibbe thought he had created; now, two decades later, there are copies for sale that cost less than the original RRP and DrivethruRPG sells a PDF for $6 (without the slipshod reproduction that ruined the PDF rulebook). Background The scenario is set in the realm of Hampton, which is one of those place names that sounds very Olde Worlde if you're American, but not if you're British. Nearly a century ago, High King Higmar ordered the construction of Thornburg Keep and its underground sanctuary to house a precious healing artifact, the Vemora. Then a plague arrived that proved resistant to all medicine and magic and Higmar ordered the evacuation of his stronghold. Since then, monsters have moved in to inhabit the underground levels (as they do!) as well as a couple of groups of marauding humanoids (Higmoni and Ghantu) looking for loot. The Vemora itself remains hidden and inviolate, deep underground. The Hook Rumours of adventure bring the PCs (rootless mercenaries, as per standard) to the village of Dunnerton. Recently, the monster known as a Cavasha attacked the village and blinded its defenders, including the Elder's son. The Elder wants the PCs to hike out to Thornburg Keep and retrieve the Vemora, to use its magic to heal his son. If good deeds aren't a motivation in and of themselves, he'll pay 300gp. A scout will take the PCs to the dungeon entrance and a local Elven healer will accompany the party out of sheer goodwill. The cover of the book (by artist Paul Butler) depicts the very Lovecraftian Cavasha attacking the village. It's an exciting scene, with villagers falling blinded after it uses its gaze power. Unfortunately, the Cavasha itself never features in the scenario, so this picture is a tease, really, since the Cavasha definitely lives up to what the rulebook calls its "gruesome appearance" (p165). The buildings in the village and the style of dress (breeches, lace collars, jerkins) suggest a 17th century setting, rather like Europe during the Witch Trials and the Wars of Religion (or perhaps Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay). I wonder, is this really how Mark Kibbe envisaged Juravia? It's certainly very different from the Post-Holocaust/Dark Ages vibe I detected in the rulebook. Dunnerton Dunnerton is sketched out in essential detail only. There's a Dwarven smith, Brundle Jove, who will offer free armour and weapon repairs to PCs working for the Elder; however he has a finite number of repair kits so there is a limit on the number of APs he can restore. A Sprite trader named Dya Brae runs the store and a list of the resources she has for sale is provided along with the exact amount of each (e.g. she has 5 Healing Roots in total). Alongside her wares, she dispenses some in-character dialogue that mixes inane wittering with nuggets of good sense. The Drunken Dragon Inn offers lodgings and a brief rumour table: the untrue rumours are far more interesting than the actual dungeon itself, which begs the question why the author didn't make use of these ideas! There's a temple of Shalmar, Goddess of Healing and the priest, an Elf named Jacca Brone will accompany the party if they need a healer. His character sheet is provided in full along with some pointers for the GM to roleplay him. There are no subplots going on in Dunnerton, which is always a shame, but the scenario is explicitly pitched at first-time-roleplayers so perhaps that extra layer of complexity is unnecessary. I like the recognition that local smiths and traders don't have unlimited supplies to service adventurers. Providing Jacca Brone is a nice touch, especially if newbie players neglected to take the Binding Skill or avail themselves of a Berethenu Knight. The presence of a Temple of Shalmar left me scratching my head. The gentle Shalmar was murdered by her brother Necros during the God-Wars. Indeed, this blasphemous crime seems to have triggered the wrathful return of Enigwa and the Banishing of the gods from Juravia. What can go on in a Temple to Shalmar? How (and why) do you worship a defunct goddess who can neither respond to prayers nor acknowledge worship? Maybe Shalmar-worshippers are a bit like certain Church of England Vicars: they don't really think their deity exists, but they respect the sort of things she stands for. That's nice, but why a tiny community beset by monsters would support a temple to the beautiful concept of healing, rather than building a temple for and funding the services of, say, a real live Grom Warrior who can kick monster butt, is a pressing question in my mind. The Dungeon, Level 1 The back cover art shows the scout directing a band of adventurers towards the dungeon entrance, which is a broken door set in the hillside, surrounded by carved pillars and steps and all overgrown with ivy and moss. The party includes a big barbarian warrior with a hilarious bald-patch, what look like a dwarf and an archer and a Merikii with his signature two-sword pose. Dungeon level 1 has 32 rooms, very much in the densely-packed Gygax-style rather than the sprawling Holmsian aesthetic. If the PCs press on in a straight line they will pass through the two entrance halls, the Dining Hall and the Great Hall, ending up in the Library where they have to tangle with a Tenant, which is a Mimic-like creature that inhabits wooden objects with a very nasty attack. Along the way, they will come across lots of mosses to test their Plant ID skills on, magical fireplaces which add a much-needed spine-tingling moment to proceedings, possibly find a magic dagger and end up securing some valuable tomes and clues about the nature and location of the Vemora. They will also have a modest skirmish with crab monsters and possibly fall through one of those pit traps that deposits them in the abandoned cell block in Dungeon Level Two, with all the fun that this implies. The trap only triggers if the party numbers 3+, which is an elegant touch: small parties (or cautious ones) are spared this complication. Rooms 1, 2, 4, 5 and (mind the pit trap) 30 take you to the Great Library (#32) and a nasty monster If the PCs venture away from this central spine, things get a bit more varied. Up to the north there are acid-spitting crabs, a teleportation gateway that takes explorers directly to the Royal Chambers on Level Two (but allows them to return, unlike the pit trap), giant rats, giant centipedes, minor trinkets and a guard room explicitly intended to be a safe base for adventurers to make camp. Those who have played D&D Module S1 (Tomb of Horrors) will be wary of this North definitely equals 'safe' and the teleporter offers the intriguing possibility that hapless PCs could blunder straight into the Vemora's hiding place - but of course they won't have the special keys needed to get at it yet. This offers a cute glimpse of where the PCs need to end up and a way of getting there quickly once they've assembled all their keys and clues. The southern rooms are a bit livelier. There are armouries to ransack, more rats, crabs and blood-draining bats to fight as well as a Creeper, which is an acidic slime. There are mysterious tracks to decipher (cue: Tracking and Track ID skills) that reveal you are not alone: Shirek, a tough Ghantu, and his Higmoni henchmen are camped down here. Shirek is the main 'Boss' on this dungeon level and there will be a communication barrier unless someone speaks Ghantu or Higmoni, in which case a fight can be avoided. The set-up here is exemplary: first the signs of ransacked rooms, then the tracks, then the Higmoni, then the appearance of their one-eyed boss. The designer makes some questionable assumptions. The main rulebook introduces a Languages skill but doesn't encourage anyone to learn it, saying "all character races ... speak a common language known as Juravian" (p23) but at the same time each character "is fluent in its own language ... as well as the Juravian language" (p5). The chances that a group of PCs will not include at least one bestial Higmoni or giant one-eyed gorilla Ghantu are (knowing the aesthetic choices of dungeon-bashing players) slim. This means players are highly likely to defuse this encounter non-violently unless they are immensely dunder-headed. But this is supposed to be a teaching dungeon, so that's probably how it should be. The Dungeon, Level 2 The lower dungeon level has 27 rooms, arranged in a sort of loop, with a spur off to the north (the old cell block where the pit trap deposits you) and the south-east (the Royal Chambers where the teleporter takes you). There are several ways down here. The pit trap is the worst: you're in the old cell block, with giant spiders nearby, and you don't know the way out. The teleporter is better: you discover the Royal Chambers and all their loot (including magic items and a magical sword) but you probably cannot open the difficult locks. You can stumble into the eerie throne room but you probably won't have the keys to get into the Vemora's vault. Try exploring further and you encounter the ravenous undead in room #36 (see below). Conventionally, you'll descend the stairs in the southern part of the first level. This brings you into a central columned hall with a fountain, magical roots to identify and the corpse of another Higmoni, tipping you off there are more raiders down here. Have fun exploring the temple rooms, dealing with killer mold and a Berethenu Shrine, which is a great asset for Berethenu Knights and offers a cute benefit for Grom-ites who choose to desecrate it. You soon discover the bedrooms, workrooms, smithies and studies of the castles old occupants and some of their correspondences. This is clearly inspired by the chambers of Zelligar and Rogahn in Mike Carr's seminal D&D Module B1: In Search of the Unknown (1979). There's a pleasant frisson to exploring the intimate chambers of these long-dead people and it's a valuable reminder that this labyrinth was not always a malevolent dungeon. There are a lot more Higmoni down here, split into two groups and leaving evidence of their looting all over the place. They're having a spot of bother with a pack of undead Magouls (why MAgouls? why not just ghouls? why???), so, once again, players who prefer to talk than fight might be able to negotiate something. The Magouls (that name, grr-rrr) are in room #36, which isn't keyed on the map, but it's the room outside the Throne Room #56 (perhaps another reason for smart players to double back and use the teleporter upstairs). Unkeyed room is #36, just off the main corridor (#33) and the only way through to the Throne Room (#56) Once the PCs have their three keys, they can head to the Throne Room (which may or may not involve confronting the undead) and retrieve the Vemora - naturally, its a big golden chalice. Then it's back to Dunnerton for the reward. Evaluation: non-Forge As noted, this is an exemplary tutorial dungeon for a novice group of D&D players. It has all the best features of Basic D&D Module B1, while being tighter and more focused. It's an underground fortress with a lot of empty rooms containing interesting objects and a few mystical moments when the magical fires light up; there are dungeon raiders who pose a challenge but can be negotiated with if the players aren't too trigger-happy; there's a pit trap to the lower level; there's a historical mystery in working out what the rooms once were and who inhabited them. In some ways, it does its job better than Module B1: the quest for the Vemora, and the collection of keys to unlock it, gives structure and purpose to the adventure, rather than aimless wandering. The nearby village of Dunnerton offers support and healing as well as a grand reward. D&D conversions are easy: giant centipedes, rats and spiders (albeit large spiders in D&D terminology) are standard; use stirges for Ebryns and fire beetles for Nemrises; 1HD piercers work for Bloodrils; the Creeper is an ochre jelly; the Tenant is hard to translate but a half-strength mimic would work (3 HD, 2d4 damage). The Higmoni can become goblins, their Leader a hobgoblin, Shirek the Ghantu translates as a bugbear or a gnoll. The Magouls are, of course, proper ghouls with proper names. The limitation of the scenario is that this is all it is. Exemplary tutorial dungeons are all very well, but D&D 5e includes The Lost Mine of Phandelver in the Starter Set, which is a far more ambitious introductory adventure than this. Even back in 1998, the sort of dungeon adventure The Vemora provides was pretty dated: it might perfect the formula of In Search of the Unknown, but that means perfecting something already 20 years old at the time. Nonetheless, if you play any sort of OSR RPG or any iteration of D&D and come across a cheap copy of The Vemora, don't disdain it. It's a little gem of an introductory dungeon that provides the right balance of mystery solving, exploration, combat and a sense of wonder. There's a bunch of noob adventurers out there who will remember it fondly if they get a chance to cut their teeth on it. Evaluation: Forge & adapting the scenario Although it's a great tutorial dungeon, The Vemora is a frustrating product for Forge Out of Chaos. Even in 1998, it was unlikely players were coming to a RPG like Forge as complete noobs. The rulebook makes few concessions to novices, since it commences with a treatise on the Kibbe Brothers' distinctive mythology rather than explaining what roleplaying is. It's very worthy that the scenario carefully points out every opportunity PCs have to use and check skills like Plant ID, Tracking and Jeweler but these sort of training wheels are certainly redundant. Instead, Forge players will be hoping the scenario sheds light on what's distinctive about Forge as a RPG: its themes, setting and conflicts. Yet here we are disappointed. The Temple of Shalmar and its priest Jacca Brone only goes to show that the authors have not grasped (or simply forgotten) the implications of their god-free setting. Forge promises a post-apocalyptic world, but the scenario presents a rather orderly one, with its well-run kingdom and 'High King'. The dungeon is not the mansion of a fallen god but something much more prosaic: an underground fortress that's only 80 years old. The ancient plague hints at darker designs, but is never explained and finds no expression in the dungeon itself: where did it come from? where did it go? why was it immune even to the Vemora's healing power? Then there's the hideous Cavasha from the front cover. With 25+1d6 HP and Armour Rating 4, it's a tough opponent but not beyond the means of a party of adventurers who have availed themselves of magical weapons. With Attack Value 3 and two claw attacks for 2d4, it's a Boss-level combatant for starting PCs and of course there's the permanent blindness from its gaze - though the Vemora's on hand to cure that. Surely the Cavasha, rather than those preposterously-monickered Magouls, should have its lair in room #33.

POST SCRIPT: This file offers a complete conversion to O/Holmes/BX/AD&D:

Developing the Dungeon The Rumour Table at the Drunken Dragon Inn suggests some other, far more interesting, plots within the dungeon. For example, there's the obligatory previous-party-of-adventurers who entered the Keep and never came back. Wouldn't it be better if some of them were still down there, wounded, starving and desperate? There's a rumour about the water being infected with the Plague: that's a good idea! The High King's ghost is supposed to haunt the Throne Room: Forge doesn't do spirits and incorporeal undead, but what if the Plague raised its victims as zombies? What if those previous adventurers are infected by the Plague now? What if there's a cure for it somewhere in the dungeon? What if the cure requires the ichor from a Cavasha's eyeballs? A dungeon like this needs a Dungeon Constable or Dingleman and it makes sense to cast Jacca Brone in this role (which makes more sense than a priest of Shalmar). The Referee has a choice: are the PCs chartered to enter the Keep by the current King, in which case Jacca is an ally who will show them in and offer directions to the Great Hall and warn about Higmoni incursions. Or (more likely) Jacca enforces the quarantine on the site and the villagers of Dunnerton are going behind their lord's back by recruiting adventurers to trespass on the site and retrieve the Vemora. In this case, Jacca is an adversary and wandering monster (on the 1st level) who must be avoided at all cost. If you add the Cavasha to the dungeon, then the Dingleman will know that it lairs somewhere on the 2nd level; he probably warned Dunnerton of its approach when it went marauding out last month. If the PCs have a (self-appointed) mission to destroy it, the Dingleman might allow even unchartered adventurers entry and guide them to the stairs - but will expect them to hand over treasure and magic items when they leave (including the Vemora - it's a royal heirloom). That creates a dilemma since the PCs swore to bring the Vemora to Dunnerton... See how much fun Dinglemen add to a dungeon? Mark Kibbe's decision to frame the scenario as a tutorial dungeon was a mistake, creatively and (I suspect) commercially. But if the dungeon architecture is robust - and this is - then it's easy to adapt it to a more complex story. Removing a few of those acid-spitting crabs, mutant rats and blood-draining bats is step one; replacing them with tragic plague victims and plague zombies is step two. Then there needs to be a cure among the papers in the Great Library (#32) with ingredients to be gathered from various mosses, roots and monster body parts around the site, the whole thing to be brewed up in the Vemora chalice to save the NPCs (and, by that point, PCs too) who are infected. That would be a scenario even experienced players would get behind and, even if it doesn't do justice to Forge's setting, it would pass a merry couple of evenings.

Last week I posted up a festive one-shot scenario on the Blog. It was my first attempt at a 30-minute dungeon and it was a dismal failure because it took me an hour and a half! But it was a cute tale of a dysfunctional peasant family being assaulted by malevolent winter spirits and the PCs being on hand to save them - a sort of reverse-dungeon where the PCs are defending a site and the monsters are the raiders. I took a bit of time to convert the scenario to Forge Out Of Chaos as part of my project to support this forgotten '90s heartbreaker. The finished scenario is on the Scenarios page. It encouraged me to correct a few mistakes. The scenario features principle NPCs Vadim and Vasilisa who are ordinary peasants but have special ancestors. My first draft was a bit confused about whether heroic Dadushka and witchy Babushka were the parents or grandparents. The final edit clarifies: they were grandparents to the three children and therefore parents to the married couple. This also clarifies a theme that was in my mind when composing the scenario but didn't get the sort of emphasis it needed. Vadim and Vasilisa have both turned their backs on the careers of their adventuresome parents: Vadim is no warrior fighting demons and Vasilisa is no witch safeguarding the home. They are the lesser children of greater parents; they live in a security their parents earned but which they themselves do not appreciate. Vadim doesn't even realise the awl and poker combine to make his father's magical spear Snowmaiden while Vasilisa uses her mother's wand as a distaff for spinning.

The other theme that I muddled on the first draft was the role of Morozko the beggar. I intended him to be an otherworldly figure, with his lunatic-savant babblings and his magical bag of gifts. The tattered robe of red and ermine hints at his true identity: Father Christmas.

The edit enabled me to clarify Morozko's role. Vasilisa turned him away when he came begging and this sin against the ancient code of hospitality is what triggers the family's harrowing. Morozko hides in the lumber shed, plotting revenge, but is discovered by little Nikita, who brings him food and drink. Morozko offers her a gift in return and takes her to the Kurgen - the old Howe where the winter spirits are imprisoned - and opens it. Nikita takes the snowglobe as her gift, but by doing so she unleashes Krampus and the Winterfiends. This might seem a pretty equivocal 'gift': isn't Morozko punishing the child who helped him to spite the mother who rejected him? In a way, yes, but faerie wisdom runs deeper than that. Morozko's gift to Nikita is to return her parents to her: not the unimpressive trapper and his superstitious wife, but the heroic role models that Vadim and Vasilisa can be, if they rise to the challenge of the Krampus. The snowglobe is an apt metaphor here, because Morozko is shaking the little cottage and its occupants, disturbing their peace and security, to bring out a greater beauty when the tumult settles. Of course, for this theme to come across clearly, the PCs' arrival should not be accidental. They meet Vasilisa while heading down a forest trail as night draws on, but how did they get to be there? Perhaps, earlier that day, at a fork in the road, they met an old man in blue and white who directs them down the left hand trail. This figure is Morozko, of course, and he has misdirected them - but only in order for them to pass by the stile where Vasilisa waits for heroes to come to her aid. The revised version includes some advice for the Referee in roleplaying Morozko. He won't be attacked by monsters if there are any other targets. He can navigate the blizzard and part the Holly Hedge to rescue prisoners. He understands everything going on. But he appears to be a gibbering fool. He functions as a 'Referee's Friend' since his crackpot utterances can direct PCs towards vital goals (reading the spellbook, assembling the spear, matching the wand and ring, returning the snowglobe). Ultimately, he could be used as a deus ex machina to bring about a successful resolution, but that requires some inspired roleplaying to get Vasilisa to repent her hard-heartedness and the two adults to demonstrate their heroism to the sceptical winter god. How does it work with FORGE? Forge has some advantages over straightforward D&D in a scenario like this. Most classic fantasy RPGs are games of attrition: your health, spells and weapons get used up and, once they're exhausted, you've failed. Old school D&D suffers from the fact that the PCs have so very little to lose. This can make it hard to tell one of those 'night from hell' storylines where waves of attackers come at the PCs, whittling them down. Most 1st level D&D characters struggle to survive the first whittle! Forge offers characters armour to take the brunt of damage (at least, at first) and Spell Points (SPTS) to use and re-use spells. Then, after an encounter, Field Repair can be used to restore armour and Binding can restore Hit Points, so long as the repair kits hold out. This gives the PCs a bit more longevity in this sort of scenario, meaning the Referee can torment them more enthusiastically. This helps support a group of introductory Forge characters through a night with several bruising combat encounters. Converting the scenario means working with Forge's distinctive mechanics. There are materials in the cottage and the byre that can be used as armour repair kits and binding kits; there are extra healing roots among Vasilisa's stock. Mages can sleep to regain SPTS but, since they need to sleep for at least 2 hours, they will be lucky to get undisturbed rest. However, the spell book upstairs can recharge SPTS if it is opened to the right place. Krampus himself is a ghastly threat. He's modeled on the build for a troll (two claws for 1d8+5 each!) with the added bonus of 1d6 regeneration every round. That's too tough for starting characters, even with a fully-activated Snowmaiden canceling the regeneration. But if you end up fighting Krampus, you've probably failed the scenario. The players need to talk to the NPCs, learn about Vadim and Vasilisa's parents, figure out what Nikita stole from the howe and return it, hopefully with the aid of the Wand and Ring or the Spear to get through the Holly Hedge, but Morozko could be roped in to open the way if the Referee is feeling kind.

I was looking for a short mini-dungeon to introduce some players to Forge Out Of Chaos - something I could convert that didn't lean to heavily on tropes specific to D&D - and along came Tamás Kisbali, posting up a link to his Eldritch Fields blog where there's a 30-minute dungeon called 'The Golem Master's Workshop.' The 30-minute Dungeon Challenge was devised by Tristan Turner on his Bogeyman's Cave blog and it goes like this: "I will sit down for 30 minutes and write 10 rooms/encounters for a short mini dungeon ... here are my general guidelines for what I make when writing one of these dungeons: a Hook, General Background, 3 Combat Encounters, 3 "Empty" Rooms, 2 Traps, 1 NPC, 1 Weird Thing To Experiment With, some Treasure, a Magic Item." Well, that's just fantastic, isn't it? It demands to be done! But first I looked at Tamás Kisbali's contribution and decided his Golem Master mini-dungeon was perfect for my purposes. You can download his original version here or my Forge conversion over on the Scenarios page. SPOILERS AHEAD if you're hoping to play through it because I'm going to offer up a session report and a bit of analysis about Tamás' excellent construction work. The Golem Master, creator of pricey artificial servants, hasn’t been seen around for some time. His house stands dark and silent. Dare you enter? Tamás Kisbali's crisp introduction paints an intriguing portrait. Here is a world where golems are made to order by master enchanters. Not the lumbering monsters of D&D bestiaries in their clay, stone, iron and flesh iterations. No, these "pricey artificial servants" are supernatural cyborgs, androids ... simulacrum, as medieval philosophers called them. Strip away the fantasy veneer and this is a SF premise: a robot maker, deep in his mansion, has been making compliant replicants but now something has happened to him. Sounds like a job for a Blade Runner. But another theme is at work. Read through the scenario and the names jump out: not just golem but Jakov and Boax. The Hebrew (or erstaz-Hebrew) language takes us to the Prague ghetto, the story of Rabbi Loew and the legends of European Jewry. The Golem Master seems to be, not just an enchanter, but a Jewish rabbi, or something rather like one. That means, what unfolds here is a spiritual fable about the gift of life and the curse of hubris. Of course, Blade Runner (1982) merges spiritual fables and science fiction, placing origami unicorns alongside those C-beams glittering in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. Sheesh. A one sentence introduction and I'm excited to get inside this one. An Open Dungeon The Workshop has the hallmark of the Open Dungeon design: an entrance chamber with no threats but three doors leading out. All directions are possible (but one door is locked). Rather like the forbidding steps down into Zenopus' Dungeon reviewed earlier. the Workshop's entrance hall provokes the imagination. You leave behind a prosaic street scene of business chatter and market vendors. You enter a place of silence and mystery. The desk ledger bears accounts of golem sales - that's the outside world of banal financial transactions - and the purchase of "of raw clay, for new personal project" - something more numinous. From the impersonal to the personal, the transparent to the mysterious: penetrating the Workshop is a journey away from the orderly and rational into madness and obsession, but also away from the world of consumption to that of creativity. It's a journey into the artistic mind that will conclude with an opportunity for the PCs to become creators and bestowers of life, for better or worse... The left hand corridor with its mud stains leads to the storeroom where the crippled golem Jakov lies dismembered, but still loquacious. His insane brother Boax can be found in the studio through the other door, pretending to be a statue and protected by his loyal gargoyles. Sequencing comes into play, because if the PCs visit Jakov first, they might recognise Boax for what he is; if they don't have that conversation, they'll be taken in by the mad golem's ruse. Another room holds a scroll than can be used to incapacitate Boax, but might find more dramatic use at the end of the scenario if the Quantum Golem is animated and runs mad. The locked room hides a great horror moment as clay hands scrabble across the floor and leap for the throats of the intruders. If the players identify and dispatch Boax before venturing downstairs, the basement offers rewards and explanations. The Golem Master is down here, maimed and quite mad, determined to complete his gigantic Quantum Golem. His patchwork abominations, built to guard him down here, are a concession to necessity, but also embody his fractured mind, magical creations with all beauty ruined. The Quantum Golem, if animated, makes a formidable ally but that scroll might be needed if it runs amok. The players are taking their first steps down the path that the Golem Master has trod before, bestowing life recklessly and bearing the bitter consequences only later. It's a Rat Trap - and you've been caught! If the players fail to identify Boax, he will trap them below stairs. The Open Dungeon turns into a Rat Trap and events down below become much more fraught. Possibly not understanding what has happened upstairs to block their exit, the PCs explore the basement and find themselves in a tense game of cat and mouse, with the cackling Golem Master in the shadows and his gruesome Abominations leaping out to attack. Someone will fall through the floor into the clay pits, which represent the raw id of the Master's imagination, now stripped bare and exhausted. A confident DM can make the Master eerie and upsetting, but the Abominations don't pose too much of a threat. The real dilemma is whether the PCs should animate the Quantum Golem in order to break out. If it doesn't go mad, they can use it to smash through the trap door and clobber Boax; if it goes crazy, that magic scroll might incapacitate the creature once it's served its purpose. There's a substantial treasure trove for low level characters, but the biggest treasure is the Quantum Golem, assuming it stays sane. Adapting for Forge The Forge conversion is easy because the monsters are original creations. Unarmoured monsters in Forge are quite vulnerable to being ganged-up on, even if they have a high Armour Rating (AR). To counter this, I've given Boax the partial resistance to blunt weapons you find with zombies and also made the Quantum Golem's stone exterior capable of notching weapons. I decided on a name for the Golem Master: Belazal nods to the creator of the original golem in Jewish folklore, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel. A significant change I made was the spell scroll. To aim for authenticity, this is now an instruction manual for deactivating golems, removing the empowering magical letters (spelling emeth or 'truth') from their foreheads. It can be used repeatedly, so long as the PCs have Spell Points left. I moved it from the unlocked bedroom to the locked study: I figure if the players break into a locked room and fight grisly disembodied hands, they should be rewarded with something potent, but the 'key' to the scenario shouldn't be left lying about in the open. The players will need it, because I've intensified the drama downstairs. Belazal will do anything to see his Quantum Golem completed, but, if this is done, will order it to attack the PCs (such gratitude!). The Quantum Golem has to keep making saving throws to resist going crazy every time it is given an order, every round it spends in combat and should Belazal ever be killed. This means the PCs are almost certain to end up fighting it if they reanimate it, but hopefully only have to endure a few rounds of battering from its terracotta fists before it goes on a rampage across the city. I added in the (incomplete) female golem Lizbjet to explain Boax's rage against his creator. Boax thought that Lizbjet was to be for him, but of course the Golem Master made her for himself (in what capacity, you may let your prurient imaginations loose). Boax's rage is Oedipal: he assaults and castrates his 'father' to assert his sexual autonomy but is trapped by the consequences of his crime, since only the Master can make Lizbjet live, yet if he does, she will love the Master, not Boax. There's perhaps little the PCs can do to alter these outcomes, but understanding the interpersonal conflicts at play makes the dungeon more satisfying and there might be leverage here if the PCs can promise Boax that they can animate Lizbjet - or make him believe they can persuade Belazal to do so. So, how did it go? Two characters (Rammstein, a Dunnar necromancer and a Renny Squirmfoot, a Jher-em warrior) entered the workshop. They enjoyed the puzzle aspects of working out what had happened. They made their way to Jakov first of all, then opened the study to fight the many hands. However, they didn't explore the studio carefully enough to expose Boax and went straight downstairs (though they did drop a gargoyle down there and it went crashing into the clay pit). Once they were in the basement, Boax trapped them down there. The Abominations didn't cause too much trouble, but Belazal was a fun lunatic to roleplay. The players reanimated the Quantum Golem and were appalled at Balazal's perfidy when he ordered it to slay the intruders. Cat-and-mouse ensued, with the golem crashing after the PCs and delivering horrible wounds but the PCs keeping just ahead of it. When Rammstein killed Belazal, the Quantum Golem went mad, bursting out of the trapdoor, slaying Boax and crashing out into the street. Poor Renny died from the poisoned door trap but Rammstein successfully used the scroll to deactivated the Quantum Golem, but only after it had caused enough mayhem to make him look like the saviour of the city. The scenario lasted about 90 minutes: a perfect evening of light OSR roleplaying. It's the sort of premise that deserves a bit more time and a bit deeper consideration. That's to say, it lends itself to a lot of non-fantasy RPG games. It would be great for Call of Cthulhu, obviously, or Kult, with its shifting realities and illuminating madness. Vampire: The Dark Ages would be a fun vehicle for it too. A bigger map and a more sprawling mansion would allow Boax and his gargoyle minions to stalk the PCs. If Lizbjet were to be alive and functional - and perhaps in love with the mutilated Jakov rather than either her creator or deranged suitor - then the roleplaying aspect would be even more dynamic.