|

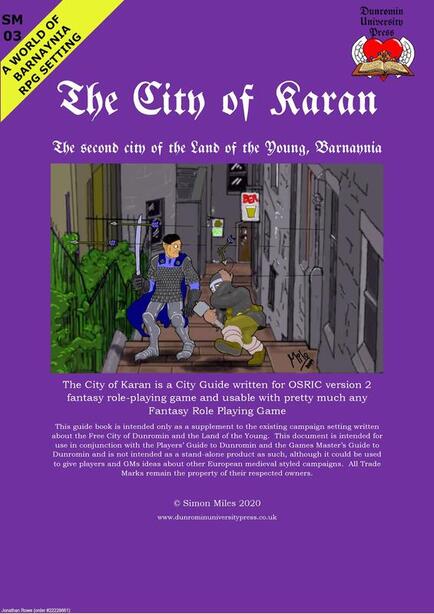

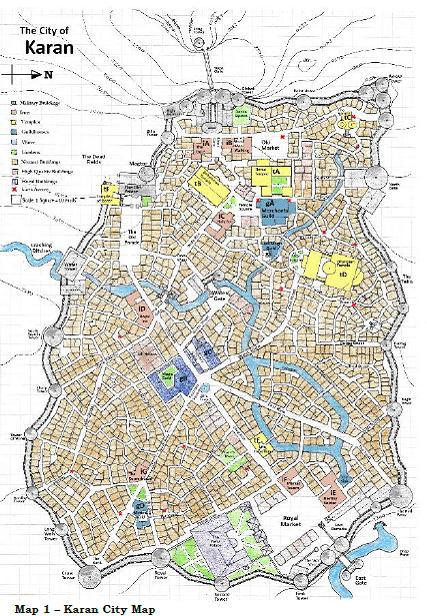

Simon "Milo" Miles is the creator of the Dunromin University Press, a massive campaign setting for his homegrown fantasy RPG using OSRIC. Now, OSRIC is a retro-clone of 1st ed AD&D, so what Simon is offering is the guiltiest of pleasures: a campaign world for AD&D as things used to be before Dragonlance, before Forgotten Realms, before Ascending Armour Class, back when Gygax was king and the TSR Wizard graced the modules and rule books. Good times. Ah, the Game Wizard! Check out OSRIC's page by clicking the image: download the rules for free In fact, The City of Karan contains hardly any statistics, so the sourcebook works perfectly well for any Old School iteration of D&D or its clones and pastiches. Simon has been developing Barnaynia, the world of his youthful AD&D campaign, and has published a wealth of settings and homebrew kits through drivethrurpg, mostly centred around his "ultimate fantasy city" of Dunromin. Back in January, he released another sourcebook for Dunromin's sister-city of Karan - and this seems like a good time to jump on board his creation and take a look around. Simon just COMMITS, doesn't he? Look at that AD&D module pastiche! Click the image to view the product - it's pay-what-you-want The City of Karan is a 70-page PDF sourcebook for a walled city in the far west of the 'Land of the Young', guarding a vital pass through the mountains. It's a border city, abutting a wilderness of roaming barbarians and abandoned ruins, but linked to the kingdom's hinterland by busy roads. In other words, it's exactly the sort of place that Fantasy RPG campaigns start off in. The dramatic West Gate with its dizzying bridge greets invaders (or returning adventurers) from the wilderness. Simon offers an exemplary discussion of Karan's history, geography and politics, first in the Players Guide section (no secrets, just rumours) and then in the GM's Section (NPCs, factions and plot ideas). His style is clear and the tone is light: a few jokes, a bit of vernacular language, it stays away from the ponderous Gygax-isms that made a generation of hobby writers think that they needed to imitate the Encyclopaedia Britannica if they wanted to sound like a 'proper' author. Seriously, I flew through this stuff. The art is ... idiosyncratic. Simon produces a lot himself, in a cartoon style, and Gareth Sleightholme provides the rest, in more conventional fantasy portraits. I'm not sure whether this larky, zany aesthetic really fits the tone of Karan or not. The Karanites have a reputation for being humourless, but look at this: If the art doesn't really work for you, don't worry, because Simon also has some excellent - and completely serious - street plans and cut-aways to orientate you in the city: What makes Karan interesting? In many ways, Karan is the oldest of old school fantasy city settings. Clerics of Norse and Olympian deities rub shoulders with Druids. There are half-orcs in the City Guarde (not sure why it has the -e suffix). People have names like Olandy Crystal or Seth Tolweezel. It's not too whacky though. Yes, there are minor air elementals protecting the battlements and a cadre of sentries mounted on griffons, but that's about as high as the fantasy goes. There's no magical market, no golems directing traffic, no mind flayer innkeepers or rent-a-zombie street corner necromancers. It's low-to-medium fantasy. The city has a medieval German vibe: cobbled streets, multistorey stone town houses, gabled rooftops, lots of turrets. It's supposed to be a big centre for craftwork and production, somewhere like Worms, Aachen or Nuremberg. Nuremberg: lovely, isn't it? The most striking aspect to the city is its cave system - a whole series of underground streets (known as 'the Creeps') with houses and shops and, beneath that, mines. This gives the city a sort of subway system, so you can pop below ground and head off down the Old Creep or the Dry Creep to emerge in a friend's cellar, the basement of a shop, or perhaps outside the city altogether. Simon invests his best efforts in giving the different parts of this undercity vivid names and distinctive appearances. It's an aspect of life in Karan that players will remember and GMs will hang many plots on. Simon also gives the fortifications and rulers of the city much coverage, including the different regiments of the Garde, the major Temples and their senior Clerics and the top government officials and their role in the lives of citizens. He also includes invaluable (because simple) tables for randomly generating businesses in order to populate any given street. It's good to see some consideration of local culture: the luxury status of wine, shops being closed for innumerable religious holidays, the autumn Beerfest, street sewers and sedan-chairs. There's a good treatment of the criminal subculture of Karan in the GM's section, including some lively personalities of varying nastiness. However, in such a well-policed society (and see below for more on this), the criminal classes are rather subdued. The book concludes with a complete NPC roster (no stats, just profiles and relationships) and an actual honest-to-goodness index. What makes Karan dull? I should qualify this, because it isn't necessarily a criticism. People use city sourcebooks like this for different reasons. Some people just want to cannibalize street plans, encounter tables and useful NPCs for their own campaign cities. In these cases, the more universal these details are the better. Karan could be a big walled border town in almost any fantasy RPG campaign and Olandy Crystal would fit well as a NPC in any scenario. Some people want a pre-designed city to act as a backdrop to their dungeon-based adventures. They want somewhere the adventurers can call 'home', where they can sell their loot and buy hirelings or magical healing or training, they want high-level NPCs to act as patrons and maybe they want to know a bit about rich merchants and the city watch so that Thief/Rogue PCs can have the occasional heist-themed 'town adventure'. If you fall into these categories, then my criticisms here won't apply to you. Karan is great for you. Skip to 'final thoughts' as Rahdo would say. But maybe you're a different sort of consumer. Maybe you already have towns/cities in your own campaign and you have no problem creating your own street plans and NPC rosters; in fact, let's say you quite enjoy that side of things. In that case, you're looking for a city that's not just detailed, but distinctive: something that you couldn't have come up with yourself. For example, maybe you want something that's culturally very specific. Maybe something exotic, like pre-Conquistador Tenochtitlan with its floating fields, canals, aquaducts and population of 400,000! Maybe just something very flavourful, like Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay's Altdorf, with its rigorous pseudo-Teutonic culture and language. By comparison, Karan is a bit vanilla. It's another Northern European walled city. Although it's supposed to have a Franco-German culture, no particular attempt has been made to convey this linguistically, through locations, titles or personal names: Samson, Molly and Dudley are more typical than Gunther or Willem in the NPC roster. You're in Gygax-land; and not fantasy-Germany. Or maybe you want a set of complex political conflicts because you're not good at plotting such things yourself. But here again, everything in Karan is quite static. The senior NPCs all get lively profiles, but they're not doing anything: they're just waiting for PCs to walk into their lives with trinkets to sell, curses to lift, training needs to be met or other services to demand. The nearest thing to NPC interaction in the city is the love-triangle around flirtatious druidess Olandy Crystal (Fighters Guild leader Alun Dethelt fancies her rotten, to husband Farnir Crystal's displeasure) but even this isn't going anywhere: Alun isn't doing anything about his amour and Farnir is too timid to make a fuss. Or finally, maybe you want a frictive setting, something that will cause the PCs problems and force players to adapt to the unfamiliar. Maybe you want to explore slavery, women-as-chattel, the divine right of kings, witch-hunting or peasant revolts. You want a city where, as soon as the PCs arrive, there's stuff they have to take a side on. However, Karan is just too darned nice. Women have a pretty decent deal in Karan, by medieval standards, if not by liberated Dunromin standards: Women ... are allowed more freedom and independence than was traditional in Europe in medieval times, but the fairer sex remain much less ‘liberated’ than in Dunromin. Slavery is not really a thing: Slaves are rare with good servants being recognised and rewarded for their skills as much as artisans The City Guarde are professional law-enforcers and don't need to be bribed: the Guarde, the force of law and order in Karan, is quite serious and energetic in the pursuance of its role ... [and will] turn up promptly when called and execute justice rapidly and fairly. Some visitors have been quite affronted when their name, contacts and gold seem to have no relevance with the Karan Guarde when it comes to determining guilt and innocence. In other words, except for the street sewers, Karan is the sort of place you would love to go to for your holidays. Remember holidays? Let me be clear, I don't want to criticise Karan for failing to be something it doesn't set out to be. If you want a detailed backdrop for a fantasy campaign whose focus lies elsewhere (such as down a dungeon), then all this cultural and political stuff would only get in your way. You want a fairly universalised setting. If everybody had culturally-specific Teutonic names like they do in Warhammer's Reikland, then it would just make them hard to pronounce and difficult to invent on-the-fly, right? If there were intense conflicts rocking the city to its foundations, it would just make it more difficult for PCs to rent rooms in an inn, hire some men-at-arms and find a Cleric to heal Derek's mummy-rot, right? With that in mind, let's go to Final Thoughts... Final Thoughts Look, when I was a teenager DMing my own (Greyhawk-set) D&D campaign, I would have LOVED a resource like this: I would have DIED for something like this. I would have used it to represent Marner, the capital of the Barony of Ratik where my campaign was set. I would have located the infamous tower one PC built within it. My plotline with the Assassin's Guilt and the Vampire Infestation would have taken place here. It would have done wonders for my world building, my sense of immersion, my use of NPCs. It would have been brilliant. If only I could send it back in time to my 15-year-old self! Ah. Memories! Then, later, in my 20s, when I was creating my own campaign settings with home-grown cultures and mythologies, I would have leapt upon this product for its maps, for its random location tables, for its details about the military composition of the regiments and the various guilds - but I would have renamed things and put my own plots and conflicts into the city. It would have been great value for me. Now, though, I'm less open to this sort of thing. I'm more of a theatre-of-the-mind sort of person, so maps matter less. I'm better at improvising NPCs with their own conflicts and drives. I like a bit of cultural darkness in my settings: prejudices, grievances, superstitions and injustices. I'm interested in political machinations, religious vocations and family ambitions. In a nutshell, what Karan offers, I don't need, and what I want, it tends to lack. But wait, stop, it doesn't end there. The current crisis has altered my gaming habits of course. I'm getting together with friends online to do RPGs and because the group is diverse and the medium unfamiliar, we're going back to classic D&D and exploring mega-dungeons, rather than all the clever-clever NPC-driven stuff I usually focus on. And a mega-dungeon campaign needs a city in the background: somewhere the PCs can go to recruit hirelings and get a Cleric to cure Derek's mummy-rot. So I'm going to use Karan for exactly the reasons I laid out above: it's an invaluable resource for a Gygaxian OSR campaign. I hope I've made clear my feelings about this product: how good it is for what it is, but how what it is might not be what everybody wants. Perhaps Simon's next setting will get down and dirty with somewhere a bit more gritty, a bit less romanticised, a bit more dynamic. But of course, a conflicted setting like that might not be so darned useful for your average roleplayer!

1 Comment

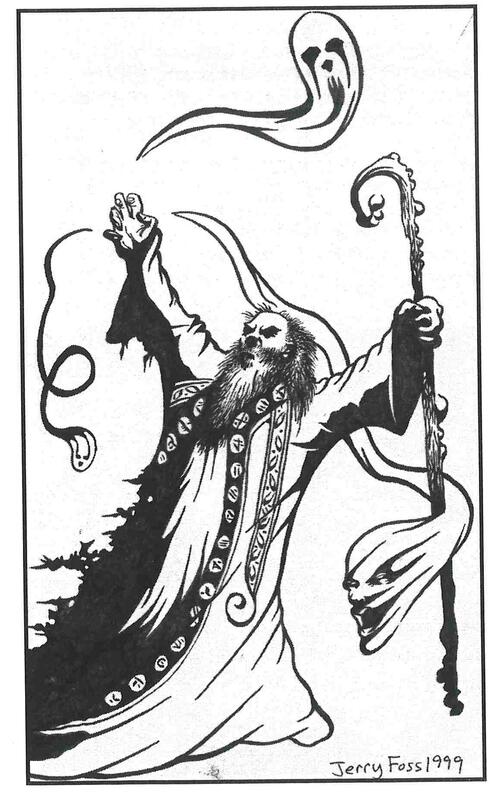

You've noticed people aren't popping round to visit as often as they did? I've noticed that too! So, to keep RPGs happening, I have to brave the Internet and get my feet wet in the world of online gaming. I decide to set up Google Hangouts, I invest in a webcam, I've got 4 players and they've got webcams too. They don't know each other terribly well. I need a straightforward, atmospheric dungeon. Someone recommends The Dread Crypt of Skogenby and I download it because (1) it's free and (2) I love the name 'Skogenby'. Click the image to go to the downloadable PDF of this scenario The scenario is written for a RPG called Torchbearer which, I must say, looks fascinating. Torchbearer claims to be an homage to early D&D, but it's a pole away from OSR. You see, Torchbearer is concerned with capturing the psychological grind of dungeon delving: the failing of light, the loss of equipment, growing hunger, exhaustion, fear... It looks compelling and complex and abstract and intense. But I'm not using the Torchbearer rules. No. I'm using White Box RPG which is about as far away from Torchbearer as you can get despite being, in essence, the original 1974 D&D rules, prettified and rationalised and put in one tidy book. It's a stripped down, minimalist affair, with hardly any dice rolls and a licence to make it up as you go along. Ideal for online gaming without miniatures, maps or complicated character sheets. Click the image to look at the White Box website and blog Why not FORGE?

Fans of this blog (if such there be) might wonder, "Why not use FORGE OUT OF CHAOS since you're always banging on about it?" and, yes, ordinarily I would. But on this occasion I wanted to lighten the cognitive load for everyone involved so we could manage the technical and social impediments of roleplaying across this new medium. So I went for a system that is the simplest to create characters for, teach, referee and improvise with - and that's White Box. Whatever distinctive complexities Torchbearer has, the shared tropes in Fantasy RPGs make conversion effortless. My players arrive at the windswept, vaguely-Yorkshire village of Skogenby, where some local teens have stumbled upon an ancient crypt. One of them, a girl called Jora, foolishly went in, found silver jewellery, passed it out to her friends and told "a tale of moldering crypts rich in grave goods" down there, but, as she crawled out, something seized her and dragged her screaming back into the stifling darkness of the crypt. The plays out like a trailer for a fantastic direct-to-streaming horror film, doesn't it? Then it gets worse. Something starts emerging from the crypt at night. It stalks the village. People are found dead in the morning, a rictus of terror on their cold faces. The victims are all connected to the crypt-robbing youths and the cursed treasure they unearthed. Now the PCs have to go down there, into that evil hole, to lay something ghastly to rest and bring back poor Jora, if she's still alive. The art is of an exceptional standard throughout The scenario itself is a small but intense dungeon. There are exactly the sort of undead critters you would expect down here, doing guard duty, and one unpleasant monster you wouldn't expect, drawn here by the necromantic energies of the place. The main task for the players is to figure out the function of this place. It's more than just a tomb: it's a god-machine. An ancient barbarian queen had herself, her slaves and her priests buried alive down here so that she could go through a series of rituals to ascend to godhood. The PCs encounter these chambers, tools and instructions and might re-enact some of the rites themselves, should they dare. Along the way there are traps and plenty of opportunities for knowledge and skills as well as brawn and bowstrings and plenty of creative speculation. Torchbearer offers interesting mechanics to keep track of time in precious torches and chart the emotional and physiological fraying of the characters. It also offers contingencies called 'twists' that make events play out in a more ... entertaining ... way. They include ominous weather, mystic phenomenon, bad luck with equipment, shattered nerves and other mishaps. If you're not using Torchbearer rules, then these twists offer a deeply atmospheric alternative to Wandering Monsters. The showdown pits the PCs against the possessed Jora. Hopefully, they've carried out some of the rituals to gain mystical protection. Hopefully, the realise that the dead queen, Haathor-Vash, is still lingering here in spirit-form and is furious about the theft of her grave goods. Hopefully, they try to negotiate rather than lay into an innocent girl with swords. Hopefully. Well I hoped in vain. I think the crypt is so successful at being spooky and weird and ominous that it leaves the players, never mind their characters, rather on edge by the time they reach Haathor-Vash. In Torchbearer, your character might be so physically and psychologically drained that you're eager to parlay. In D&D and similar games, you're probably itching to hit something. The problem is that if Haathor-Vash leaves Jora (say, because you chopped her head off), she can always possess someone else. And so it goes, like that Denzel Washington film Fallen (1998), with the spirit bouncing from body to body, except in a cramped crypt while you're beset with skeletons. All of which is to say, this is a surprisingly thematic dungeon puzzle with a very tense and difficult final encounter. Strong roleplayers with a taste for the spiritual will make a feast of it, especially if the GM indulges them by characterising Haathor-Vash in a vivid way. More conventional PCs will die in the inner crypt. Yes, you figured it out: for my party, it was a Total Party Kill (TPK), with one PC, the lone survivor, becoming Haathor-Vash's new vessel, to remain in the crypt, in the darkness, alone. Brr-rr. But that feels right for the doomed horror-stylings of this scenario. What Can You Make Of It? Firstly, the scenario functions as a fantastic advertisement for Torchbearer RPG and I'd defy anyone to read it and not want to know more about Torchbearer. The scenario might be set in a dungeon but it plays out rather more like Call of Cthulhu than Dungeons & Dragons: there is a distinctive and evocative ancient mythology to untangle, skills in scholarship and the occult matter just as much as combat, when you reach the showdown you have hopefully engaged ancient arcane forces on your side. Most interesting is the psychological attrition as characters move to being weary, hungry, exhausted and afraid. The combat seems to be pure theatre of the mind, with an emphasis on dread and caution rather than swashbuckling heroics. This dungeon is CLAUSTROPHOBIC and Torchbearer seems to be a system that's all about conveying the emotional pressure of entering such places, like a more complex and nuanced version of Call of Cthulhu's ever-diminishing Sanity score. Or you can do what I did and convert it to an Old School RPG system. This is easy enough: skeletons are skeletons and oozes are oozes. The stat block for Jora/Haathor-Vash needs some thought, but I treated Haathor-Vash's possessed victims as half-strength Wights and the effect of the Ritual of Purification being to acquire Protection from Evil on your person, keeping the Wight's level-draining claws from touching you. Despite the text and cover art that has Jora wielding it, I decided to make Haathor-Vash's sword available for a PC to seize and upgraded it to being magical+1, just to even the odds. The problem with any OSR conversion is that you risk missing out on what this scenario is all about: claustrophobia, dread, ancient rites, the sense of a haunted and malevolent place rather than just a 'dungeon'. Of course, sensitive GMing can make up for that through atmospheric description and the 'twists' offered in the text go a long way to help with this. Nevertheless, as I found, the genetic code of D&D is hack'n'slash and that can overturn the conclusion, which in Torchbearer will probably result in negotiation or a PC rout (and frantic flight through the halls and out through the narrow tunnel with undead fingers clutching at your ankles) but in D&D invites straightforward TPK. Simply adapted as a 'dungeon', the scenario has its merits. It's small and focused, suitable for a single 3-hour session, offering puzzles, traps and a bit of combat before the climax. But I feel that D&D-style games fail to capitalise on the experience that The Dread Crypt of Skogenby has to offer. I could see it working really well in The One Ring RPG, as a thoughtful variation on standard Barrow Wight activities: that game also charts spiritual/psychological deterioration as much as physical harm and emphasizes mood and character rather than muscle and combat. It would even work in Pendragon as an unusual horror-themed digression for minor knights, again because that game focuses on character traits and the conflict between Christian and Heathen values. And of course, it would be fun to use Call of Cthulhu - nothing about the setting demands a medieval time frame and it would play out just as well in 1920s Scotland or Yorkshire.

Over the last couple of months I've created a half dozen scenarios on this blog, which have met with a warm reception (or at least, not outright hostility). They were originally part of my promotion of Forge Out of Chaos RPG, but they track my growing engagement with OSR RPGs - especially Holmes Basic D&D. So it seemed like a good idea to adapt these scenarios specifically for D&D (non-denominational and retro-clone) and put them in a document on drivethrurpg. It's called the FEN ORC ALMANAC 2020. Click the image to go to the publication But aren't all these scenarios freely available on the blog? Well, yes, they are. But...

This feels like a fine way of delivering those scenarios in a 'finished' format. Yes, the old references to Forge have been excised but the advice for GMs for using Basic D&D/AD&D or various OSR retro-clones has been given priority. Perhaps, with the current crisis taking shape, I'll find myself with a lot of time on my hands to write more scenarios! I pray we're all here for Fen Orc's 2021 Almanac - take care of yourselves.

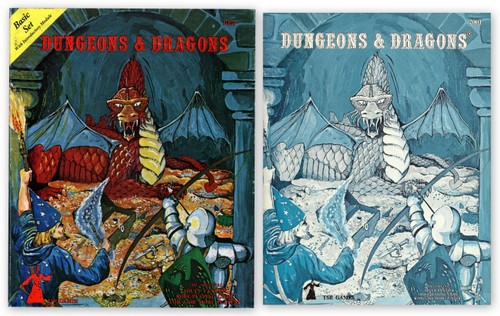

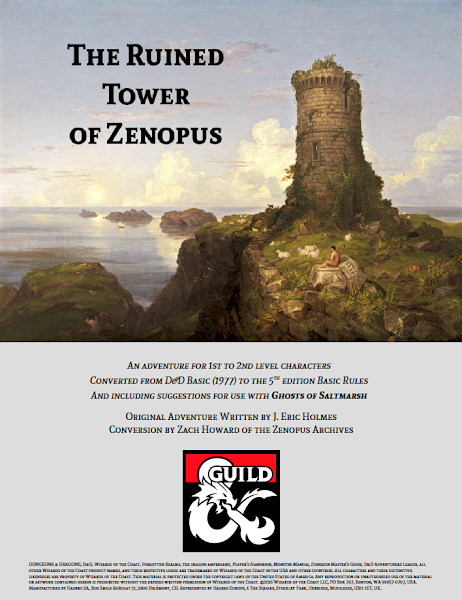

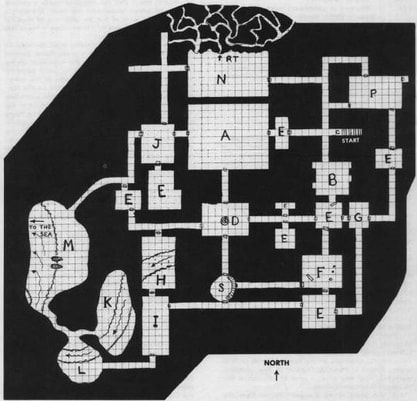

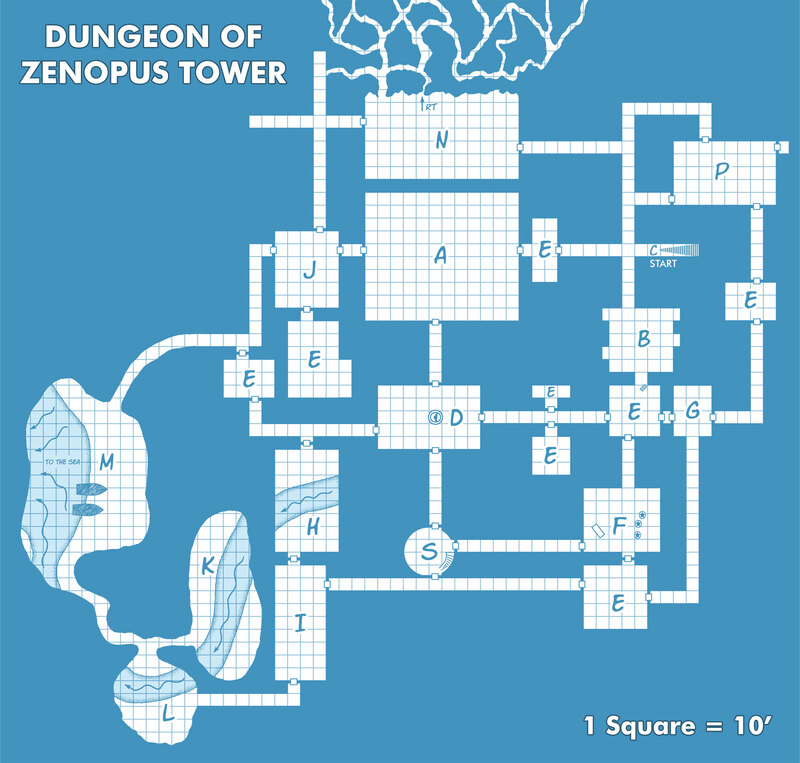

We are entering the post-modernity of roleplaying games. The author is dead. How quaint it is to look back on the modern era (the 1970s and ‘80s) with its assumptions about authorship and ownership, of texts with single discourses, of official ‘canons’. It’s not like that now, what with retro-clones and open gaming licences and Old School Revivals. An old Boomer like me can only shake his head in wonder at what the young folks are getting up to with their fancy notions. Take classic dungeons. They're all being revisited: Saltmarsh, the Tomb of Horrors, the Temple of Elemental Evil. Sometimes they've been changed beyond recognition. Break the old structure up and burn it for fuel. But one dungeon has stayed pristine and free from the revisionists: the hoary old Zenopus dungeon. Context first. Back in ’77 when Eric Holmes published the first Basic D&D Rules, the set included a sample dungeon to introduce utter noobs to roleplaying. It was so ahead-of-the-curve it didn’t even have a grandiose name, but it’s variously named ‘the Zenopus Dungeon’ or ‘Zenopus’ Tower’ after the mad, bad wizard who built it. I review the dungeon on an earlier blog and try to analyse its charm, the captivating mixture of fairytales and Lovecraftian horror that animates Holmes’ vision of D&D. Enter stage left, Zach Howard, AKA Zenopus Archives. Zach has made it a work of scholarship and personal piety to excavate and celebrate Holmes’ vision of D&D, promoting the Holmesian Basic rules, offering deep dive analyses of Holmes’ writing and generally promoting an ethos of adventuring that has a romance to it that was (arguably) squeezed out by the corporate contours of TSR and later Wizards of the Coast. You should check out his website and blog: it’s great. Like Jack and Rose in Titanic, Zach and the Zenopus Dungeon have been on this collision course from the start, so it’s amazing it took this long for Zach’s 5th edition adaptation of Holmes’ dungeon to appear, courtesy of DM’s Guild. You can pick up the PDF for $1.99 and why wouldn’t you? It’s a classic dungeon, dusted off and drenched in love. Available from DM's Guild, $1.99 What Do You Get for Two Bucks? Two bucks buys you 18 pages, faultlessly formatted and a beautiful cover painting (Thomas Cole’s 1838 Italian Coast Scene with Ruined Tower) that seems to symbolise the whole project: the crumbling tower is the monument of Holmes’ Basic D&D; the idyllic shepherd tending his flock in the shadow of the tower, that is Zach; the little boat out among the islets, that’s us, wondering if we should put ashore: in a moment the shepherd will stand up and wave to us to drop anchor. There’s treasure here, you see, that Zach knows about, in a place long neglected. Zach introduces the scenario in its original context, quoting from Holmes’ text. Whispered tales are told of fabulous treasure and unspeakable monsters in the underground passages below the hilltop, and the story tellers are always careful to point out that the reputed dungeons lie in close proximity to the foundations of the older, prehuman city, to the graveyard, and to the sea Brr-rr. It still gives me goosebumps, that final triad: the prehuman city… the graveyard … the sea… the imagination is drawn into the occult past, into the mystery of death, into the hope of transcendence. Holmes could turn a phrase. Zach respects Holmes and his copyright by only quoting fragments of the original and artfully synopsizing the backstory (hubristic Wizard digs too deep … BOOM … only ruins left … dungeons ignored for a century). There’s a new map of Portown itself, orientating the dungeon entrance with the town, graveyard, sea cliffs and other sites. One of the features of the scenario that was so surprising in '77 was the way Holmes’ dungeon interacted with the above-ground setting, something which other products in the early days of D&D failed to follow up on. In Appendix C, Zach offers a d20 rumour table which incorporates many of Holmes’ contextual touches, adding a few more useful ones to inform players (such as the disappearance of Lemunda the Lovely) or misdirect them. Zach offers a ‘short form’ rumour table and a longer discussion of each rumour, with dialogue to read aloud and reflections on how each rumour relates to the dungeon itself. This introduces the delightful possibility of PCs entering the dungeon by entirely different routes. Zach also offers something that Holmes neglected: a bespoke Wandering Monster table for the site. Most of these wanderers are inhabitants of the dungeon on the move – or else their allies and cousins, that’s up to the DM. There are some sweet new additions, such as a dungeon cleanup monster (scaled to alarm but not overwhelm new players) and cultists, of which more anon. After all this, we get the dungeon itself. There’s no map – copyright issues, once again. However, Wizards of the Coast make a PDF of the original dungeon available on their site and the Internet also has fan-made maps, some of them rather lovely. A caption box introduces each of the 18 dungeon locations, quoting from Holmes where necessary. The explanatory text contains sections like “Treasure” or “How It Works” to help inexperienced DMs navigate the dungeon. Some of the treasures (especially the magic weapons) have been tweaked in a colourful way. Experienced DMs will turn to the “Options” paragraph which offer suggestions about what to do with the original empty rooms, how monsters might be beefed up or how they might interact with adventurers in novel ways and how room contents might link to some of the new rumours in Appendix C. Everything is adapted clearly to 5th edition rules and the new additions are also adapted back to the Basic Rules if you prefer your dungeons to be thoroughly Old School. Zach gives the rooms names, which Holmes neglected to do, and some of these are charming or goofy or else hint at dread and mystery. In other words, the exact same cocktail that Holmes employed. One notable optional addition is the presence of evil cultists, ransacking the graveyard to raise the undead with horrid rituals. These villains are extrapolated from Holmes’ background and add an element of menace to the dungeon that I think it needs. If further justification were needed (and it isn’t), Zach directs us to The Charnel God written by Clark Ashton Smith: “one of Holmes' favorite authors of weird fiction.” A beautiful touch is the addition of a roof to the Thaumaturgist’s Tower. Yes, this is implied by the description of the room below, but Zach seizes the opportunity to present players with an uplifting panorama: The view here is spectacular. To the west are the sea cliffs over the Northern Sea. To northeast is a hill with the ruins of the tower of Zenopus, and beyond a cemetery. The streets and buildings of Portown extend to the east. Psychologically, this is an important moment: by plumbing the depths of the dungeon, the players reacquaint themselves with the surface world and now understand it in a new light. The Hero’s Journey resolves itself here. Zach, I think Holmes would be proud of this. Bravo. The text concludes with a section on adapting the adventure to Ghost of Saltmarsh, a 5th ed campaign set that I don’t own and cannot comment on, but the fit here looks pretty seamless. A selection of pre-gen 5th ed characters rounds off, with appropriate Holmesian names. Evaluation: What's It Good For? I’m not sure whether to assess this product as a work of D&D scholarship (sort of paleo-literary-ludology) or as a practical gaming resource. As a gaming resource, it’s not terribly vital. The original dungeon is freely available and the upgrade (if that’s what we call it) from Basic D&D to 5th ed shouldn’t challenge most DMs. If you are an absolute beginner, then I think Ruined Tower of Zenopus is probably just as instructive Lost Mine of Phandelver, the official introductory scenario in the Starter Set, while also being a bit less overwhelming. More likely, Ruined Tower of Zenopus will be played by experienced D&D players, chasing nostalgia and the scent of extinct possibilities, rather like listening to Beatles B-sides and demos, trying to recapture a sense of strangeness from something you love but which has become over familiar. As scholarship, Ruined Tower of Zenopus belongs in your collection as a measurement of distance travelled: like a sextant, it tells you how far away is the horizon (the inception of D&D), how much has changed compared to the ‘fixed stars’ of goblins, giant spiders, magic swords and animated skeletons. Going back to that cover painting, owning this module puts you on that little boat, sextant in hand, looking up at the tower on the cliff, getting a sense of the history of your hobby: the prehuman city of Holmes’ literary idols and psychoanalytic passions; the graveyard of Basic D&D, supplanted by Gygax’s more prosaic imagination; the sea, where we all sail when we roleplay, into boundless possibilities. Zenopus’ tower is a landmark to chart your course by. It never steered me wrong. Nor will it you.

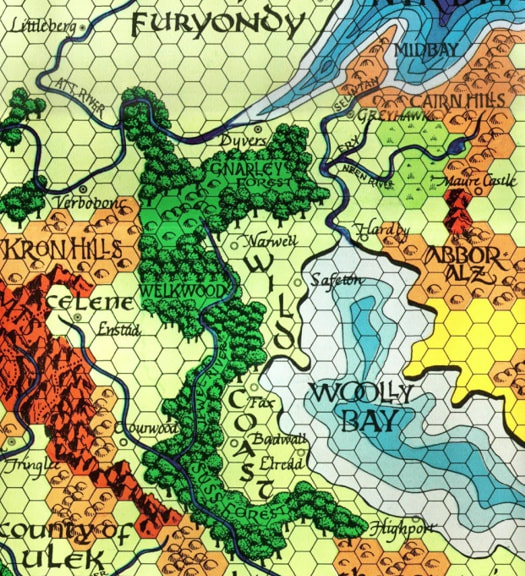

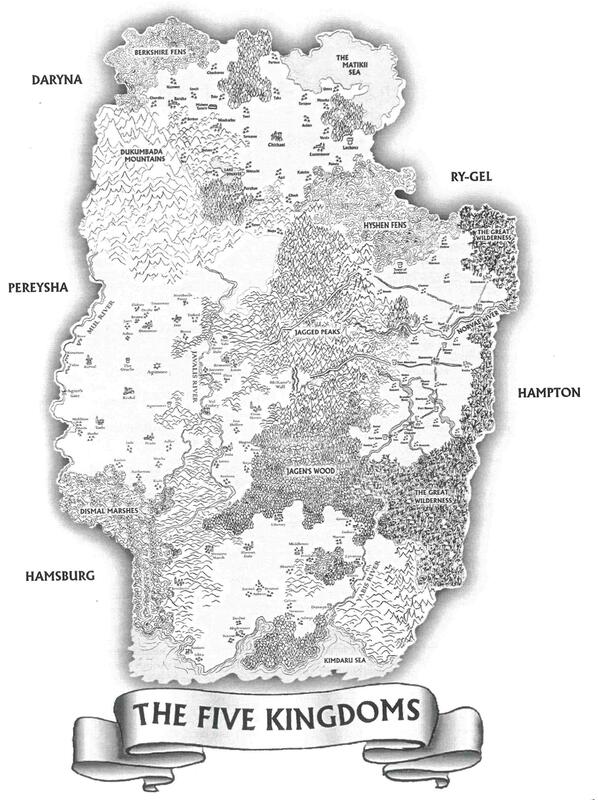

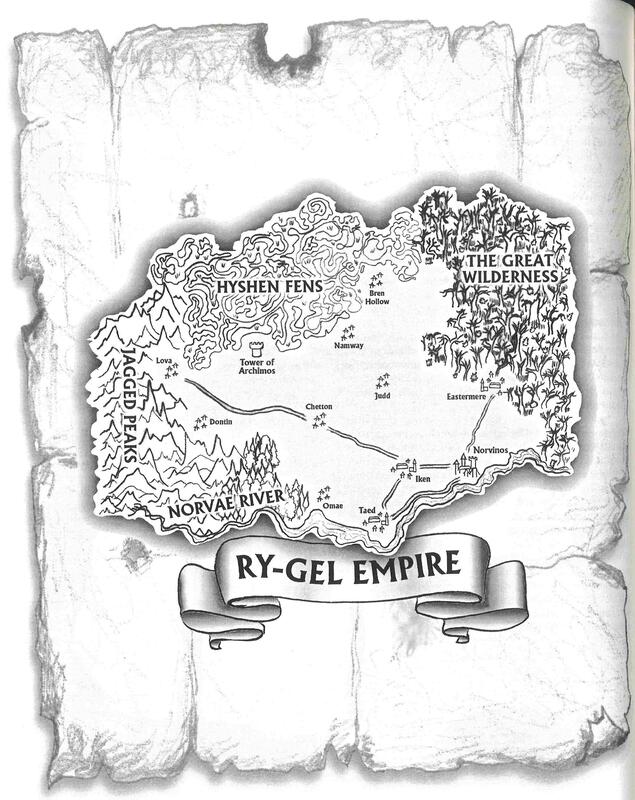

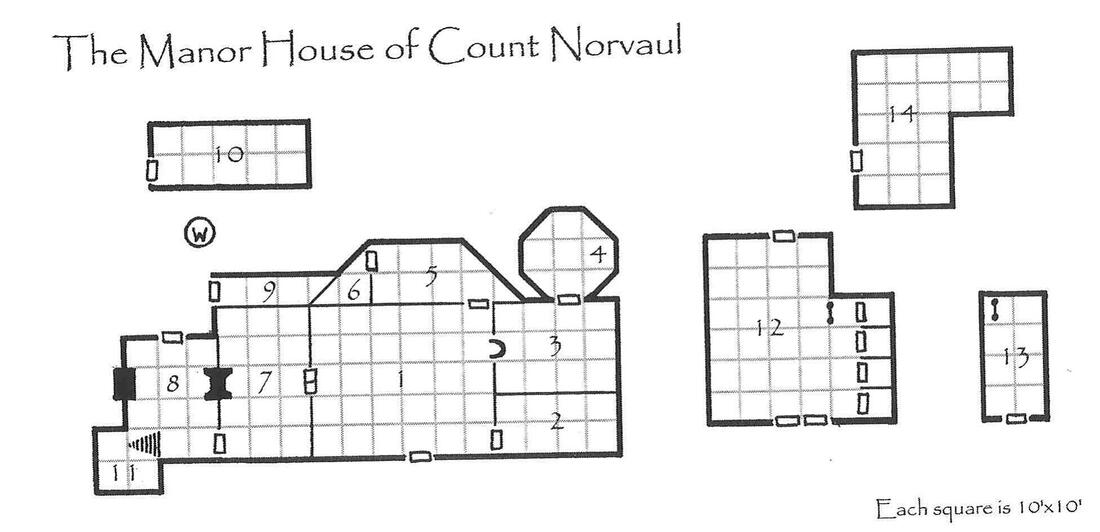

Over the past few months I've reviewed the 1990s "fantasy heartbreaker" Forge Out of Chaos and analysed its main rules, themes, monsters and the two published scenarios (The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell). It's a game with an identity crisis, setting itself up as a meat-and-two-veg dungeon crawler set in a ruined world where the gods have been banished, but then being recast as a sort of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay imitator, set in a Renaissance or Baroque world with a lot of politics, economics and a Gothic palette. More on that shortly. This is the last product to be published for Forge Out of Chaos, back in 2000. The previous module promised an ambitious campaign pack (called Hate Springs Eternal - great title) in November 1999, but that never appeared. Instead, the sourcebook arrived, rather optimistically bearing the "Volume 1" subtitle. After that, the presses at Basement Games fell silent. I wonder what was planned for Volume 2? The World of Juravia is a 170 page book that retailed for $19.95 - expensive for back then: this is the same price tag as the original Forge rulebook itself. The old team of Mike Connelly & Don Garvey is gone; there's a range of art in here, notably Jim Pavalec, who does the cover art, and Shella Haswell, who produced the back cover and has a rather different, highly stylised approach. The interior art varies a lot in quality but is mostly solid fantasy fare. Pavalec's cover suggests a return to the game's conceptual roots: a sinewy, barbaric figure (a Higmoni, judging by that be-tusked jaw) is ambushed by a many-headed snake (perhaps a Tursk, but they are supposed to have two cobra-like heads). The stylised nudity, the languid athleticism and the rearing monster, all seem to reference Boris Vallejo's art for Conan (minus the naked chicks: to its credit, Forge never went in for that aspect of old-school fantasy art). Gone are the breeches and lacy collars worn by the villagers in The Vemora: this looks less like 17th century Europe, more like pre Ice Age Hyborea. This statement of muscular intent is backed up by the back cover blurb: Welcome to the World of Juravia ... a paradise lost! Once a land graced with beauty, it is now a scarred wasteland of desolate swamps, jagged mountains, and hideous creatures beyond imagining. This echoes the contextual fluff on the back of the original rulebook: It was once a paradise but is no longer! Once beautiful landscapes are now swamps, desolate wastes and jagged mountains. The calm and gentle rain has turned to fierce storms of fire and ice. It's tempting to read this as a return to the game's roots in a gritty post-holocaust environment, rather than the genteel and civilised setting described in Tales That Dead Men Tell. What's inside? - A Calendar! Yes, we start with the Juravian Calendar and it appears to be the year 679: that's 679 years since the gods were Banished. The first 300 years seem to have passed in murky confusion but in the last two centuries there has been some sort of Renaissance and an international calendar has been developed. Four pages set out the days and months of the Juravian year and its major festivals, which honour the gods, especially Omara, goddess of harvests. There is reference to the "church of Enigwa" (the creator-god) and its year-end tradition of burning alive all wizards! Let's dispense with the oddity of kicking of your world-building sourcebook with arcane stuff about calendars. Gary Gygax did it with the 1st edition AD&D World of Greyhawk Gazetteer and if it's good enough for Gary... Yes, I assume that author Mark Kibbe followed (rather uncritically) Gygax's AD&D template for what a world sourcebook ought to look like. Critic Ron Edwards rages against this sort of thing, complaining, in his famous essay on Fantasy Heartbreakers (2002), that games like Forge "represent but a single creative step from their source: old-style D&D." But I'm rather touched by the humility of it: Mark Kibbe is homaging the World of Greyhawk, right down to Gygax's highly idiosyncratic ersatz-scholarship. But never mind that! The eye-rubbing is in the details. What was implied in the previous modules is explicit here: in Juravia, the gods are still being worshiped and that worship is led by a professional priestly class. To grasp the weirdness of this you have to steep yourself in Mark Kibbe's iconoclastic mythology - but since his mythopesis takes up the first 11 pages of the Forge rulebook, you'd be forgiven for supposing the author wanted you to do exactly that. These are the gods (let's recall) who joined together to create humanity, then set about warping and mutating humans into the demi-human races and into monsters to function as soldiers and artillery pieces in their planet-shattering war, a war which led to their banishment from Juravia, the utter annihilation of one of them and the eternal perdition of two more. Why would anyone who believed this mythology want to worship these beings? And since they cannot answer prayers or grant spiritual comfort, what would be the point? It makes sense that creator-god Enigwa would stll be worshiped and it makes sense that his 'church' would condemn Mages: in Juravian myth, Enigwa forbade the gods to teach magic to mortals. You would think the Enigwa-ists would be just as hostile to the worship of other gods, especially Gron and Berethenu, since Enigwa sentenced these two deities to Mulkra (Hell) for their role in the God-Wars. If the "Church of Enigwa" promotes Deism (the belief in a virtuous but non-interventionary God) and indulges in Wizard Burning, then we are very clearly in the equivalent of Europe's 17th century here. I don't mind that: a world inspired by the Witch Trials of Bamburg and Salem has appeal. But I'm surprised. The main rulebook gives no intimation that Mages are hated outcasts or that anyone choosing a Mage profession is putting a target on their back, courtesy of those fanatical Enigwa-ists. Moreover (and this is oddest of all), the rest of the gazetteer barely refers to it again. The Five Kingdoms - sort-of France, or maybe Massachusetts There's a map of the campaign setting of 'the Five Kingdoms' and it is (for its time) nicely done and in the same format as Tales That Dead Men Tell. There's a massive central mountain range (the Jagged Peaks) and the Dukumbada Mountains up to the north-west, creating a passage between them linking the northern and western regions. The northern kingdom is Daryna, which is suggestive of Poland, bordered by dense swamps and a sea coast. The Merikii bird-people live here and it's pretty isolated. The region is not an island - rivers, mountains and forest form natural boundaries Over to the West is a large 'empire' called Pereysha, bordered by rivers and more marshes. It seems to have a sort of Franco-German feel. There's a massive forest south of the Jagged Peaks called Jagen's Wood and that separates Pereysha from coastal Hamsburg, which was the setting for Tales Dead Men Tell and is perhaps Mediterranean in tone. East of Jagen's Wood and the Jagged Mountains (but connected to Pereysha by a strategic mountain pass) is Hampton, the setting for The Vemora; however, this version of Hampton makes no reference to a 'High King' called Higmar and the village of Dunnerton does not appear on the map. Finally, north of Hampton but cut off from Daryna by the enormous Hyshen Fens, is weird Ry-Gel, which I'll discuss in a bit of detail, since it's the most clearly fantastical of the realms. The map is only a sliver of a wider continent. No scale is given (an odd oversight) but based on the textual references, the region seems to be about 500 miles east-west and twice that north-south. In other words, these 'empires' and 'kingdoms' are squeezed into a territory the size of France. Off in the wings, beyond the map, are the larger polities of Jucumra and Brattlemere and an Elvish realm of Elladay; however, natural barriers (especially the 'Great Wilderness' to the east) lock this territory off from the wider world. The Merikii are the indigenous peoples of Daryna, but the other kingdoms are former colonies of those off-stage empires. This starts 491, with Hampton being founded by pioneers from Jucumra making their way through the Great Wilderness, like Daniel Boone crossing the Cumberland Gap. The Jagged Mountains are seething with Higmoni War Camps and in 533 these erupt out, causing the Blood Wars. Various offstage empires contribute troops and the victors carve out Pereysha over on the other side of the mountains and then Hamsburg, a Pereyshian colony, wins its independence in a brief revolt in 587. Ry-Gel seems to stand apart from these events. It is discovered by pilgrims crossing the Great Wilderness in 301, a bit like the Mormons arriving in Utah, and it fights its own battles with the Higmoni a couple of centuries before the Blood Wars, then it falls under the rule of a wizard named Nanghetti who becomes a usurper and has to be destroyed by an order of paladins. Ry-Gel stays out of the Blood Wars but is rocked by famine and plague. it bans all religion and is ruled by a corrupt and decadent Triumvirate. It is far and away the most interesting of the Five Kingdoms. Nanghetti's return from the dead was supposed to be the plot for Forge's module-that-never was, Hate Springs Eternal. The Ry-Gel 'empire' seems to be about the size of Wales Analysis The names are, I think, misleading. Pereysha is called an 'empire' and so, on occasions, are the other realms. Secundum literam, they are not: they haven't expanded beyond their national borders to conquer or colonise other peoples; they're not multi-ethnic supra-states. Calling them 'kingdoms' also seems to be hyperbolic. They're more like the duchies of Medieval France or the protectorates of Renaissance Germany. No, what they are really like are the early American colonies. Hampton, with its robust citizen militias, gender equality and big university would be Connecticut; Hamsburg with its archaic gender roles would be somewhere like Catholic Maryland; Pereysha is big, rich Virginia with its trade ties to the Old World. Daryna is isolated and full of 'natives': the Great Plains, maybe Oklahoma. Weird Ry-Gel with its pilgrims and paladins and reactionary secularism could be Quaker Pennsylvania or Puritan Rhode Island. This piece of interior art seems to me to capture the tone of Mark Kibbe's setting better than strapping barbarians or robed wizards The US Colonies analogy gives me a clearer sense of what author Mark Kibbe was reaching for. These aren't barbaric territories, despite the front cover art, but they border onto unexplored and dangerous wilderness regions. The 'kingdoms' are small in population, experimental in political structure and have a relatively short history. They're all related to each other. They're all friendly. Moreover, they're economically productive and intensely liberal. Yes, there are few quirks, like Hamsburg's treatment of women and Ry-Gel's treatment of religion, but these are very modern cultures. All of them win their independence more-or-less bloodlessly because their parent empires prefer to trade with their former colonies than hold them by force. It's like an American 'civics' class with monsters. Bad rulers are deposed, usually peacefully, by dissatisfied commoners. Ordinary people go to university. Official documentation entitles people to travel and trade (it's not clear if the printing press exists, but the political sophistication surely suggests it does). It's all quite idyllic. Which, of course, makes it a bit dull. The troubling idea of a 'Church of Enigwa' persecuting Mages is never touched upon again. Sure, bureaucratic Pereysha can be a bit burdensome for free-wheeling PCs, but despite the exemplary detail in the regional descriptions, there's very little conflict for players to get caught up in. There's not much ethnic hate, or unresolved grievance, or seething discontent. The worst people in the Five Kingdoms are the 'Rats Nest', a Thieves Guild that destabilises the Hamsburgian Province of Newton. The Rat's Nest gets a thorough description, but you still don't feel motivated either to join it or destroy it. Ry-Gel is a bit of an exception, with its mystical past, it's unusual (and corrupt) government and its intolerant laws. You can feel adventures brewing in Ry-Gel, if a covert missionary wants to preach some crazy new faith and recruits the PCs as guards - or if the PCs get recruited as inquisitors to root out cells of cultists. But the main problem is lack of cultural focus. Every village and town gets a small entry, each leading NPC gets named, but the world of the Five Kingdoms remains shadowy. There's a solid idea for a setting here, but Kibbe focuses on the peripheral details and lacks the insight into human darkness needed to imbue his world with conflict and drama. Kibbe seems to struggle to imagine that rational people wouldn't sit down and solve every problem peaceably, so that's what his NPCs tend to do. It's a world that feels SAFE and not in a good way. The Dungeon Architect The next section of the book is the Dungeon Architect which appears to be made of material originally posted on the Basement Games website. There are 24 locations, each with a clear map and key, background and suggestions for inclusion in a campaign or using as the basis for a scenario. One of the larger locations, an abandoned manor house in Hamsburg that is being auctioned off by the state and could be bought by PCs for 157gp (you see how orderly and cosy this setting is? no need to bribe clerks or flatter aristocrats in sensible Hamsburg!) The selection includes inns, abbeys, the University of Nyanna, abandoned hermitages, crypts, cave systems and temples of Grom. The value of this sort of thing is immense, offering day-to-day locations where the PCs live, relax, work or research along with more mysterious locales that an be the basis for adventures. Mark Kibbe's rather prosaic imagination is ideally suited to this sort of architecture: lots of maps, sensible room descriptions, attention to details like estate income and access to fresh water and a few rumours and legends. An entire book of these would be invaluable for anybody's campaign, using any system. The last six pages of the book are taken up with a 'Rumours' section, which also seems to have come from Basement Games' website, presumably reflecting the designer's house campaign with contributions from some of the game's fans. These are fine: any and all could serve as plot-hooks. But none of them is particularly striking: there's nothing eerie, baffling, horrifying, intriguing or epic going on in Juravia: just expeditions, bandits, criminals on the run, missing children, kidnappings, tax collection and (this is good) the burning of a magic-wielding infidel by the Church of Enigwa. You want to know more about this Mage-hunting Church and less about tax collection, but as usual the setting seems to focus on all the wrong things. Amnesia - the last scenario We never got to see Hate Springs Eternal, but the Juravia sourcebook includes the third and final Forge module, a scenario called Amnesia which holds its head up well alongside The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell, i.e. it's the sort of thoughtful, low-key adventure that would have been a classic if White Dwarf had published it in the '80s but which lacks the ambition or originality to rescue the Forge franchise from obscurity. The premise here reminds me of the old AD&D Module A4: In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords. The PCs awake in an underground cavern without their equipment and must find their way out, relying more on wits and roleplaying than conventional combat. Erol Otus' art is so witty: the PCs beat down on some small mushroom people but look what's approaching in the distance... In Amnesia the situation differs slightly: the PCs have armour and weapons but do not have any memory of where they are or how they came to be there. The scenario functions as both a trap and a puzzle, since the players must figure out what has been going on from clues they come across underground - including an angry Dwarf who knows them well and has good reason to hate them, although the PCs have no recollection of meeting him before. It's only 10 pages long, but the detail, layout and plotting is faultless. Mark Kibbe excels at this sort of thing: the classic dungeon-based scenario, done well. The players start off with limited light source and no map-making equipment and will soon find themselves in darkness, going in circles, unless they are clear-headed. Soon, they will acquire much-needed equipment and start to piece together that they are in a slave camp, with formerly-brainwashed prisoners who have been working the copper seam. The mine contains dangers of its own as well as shocks when the PCs discover that, in that period of their lives they have forgotten, they were not the slave workers in the mine but the cruel guards and overseers! There are several possible exits, one of which involves a very nasty fight with armed and armoured guards (always a tricky proposition given the way Forge's combat system works) and the other two involving an element of roleplaying with distrustful or hostile NPCs. The scenario concludes with some intrigue and politicking. The mystery is explained by the activities of one of the monsters from the Forge rulebook - a Limris, which I've previously singled out as the most original and entertaining contribution in the entire bestiary. The creature has been in cahoots with a leading Merikii Duke of Daryna, so in the aftermath the PCs are either going to accept a mighty bribe to stay silent about the Duke's involvement in kidnapping, slave labour and monster-wrangling or else set out to bring the villain to justice. Don't mess with the Merikii All of which is to say, this is A Very Fine Scenario Indeed. It could comfortably fit into two sessions but it might expand to more if the Referee expands on the aftermath. It's nice to see Merikii rather than Higmoni as antagonists (although the poor old pug-faces turn up here as well as thankless monster mooks). It's a bit more challenging than The Vemora or Tales That Dead Men Tell, offering situations and dilemmas that will put more experienced players through their paces. And yet, it falls short of what it needs to be. Kibbe takes a pride in modest threats: all three scenarios for Forge are self-consciously low-key affairs: no demons, no powerful mages, no dragons or vampires, no ancient curses or powerful relics. In this scenario, the main monster, the Limris, dies offstage - like the non-appearance of the Cavasha in The Vemora and the absence of scheming Maria Yates in Tales That Dead Men Tell. Kibbe seems to delight in creating big melodramatic plotlines and then locating his scenarios in their shadow: the players hear about but never get to meet the fantastical fiends. Yes, there's a pleasure in this sort of approach - like the 1994 "Lower Decks" episode of Star Trek Next Generation. The problem is that this sort of subdued, tangential narrative is all Kibbe ever produces. It's a bit like watching Rosenkrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead without having seen Hamlet - you haven't seen the real thing of which this story is the artful deconstruction. After three modules, we still don't know what a proper Forge scenario is supposed to look like, what the game has to offer when taken at face value. I would happily referee Amnesia as an introduction to Forge for experienced players - and it would convert very easily to D&D or other classic Fantasy RPGs - but it just isn't the sort of scenario that this product needed to sell the rather opaque 'Five Kingdoms' to an increasingly sceptical fanbase. Overall - how should we look back on this? Of course, Forge Out of Chaos passed away and this was its last gasp. Probably, the writing was on the wall for Basement Games back in 2000, but perhaps Mark Kibbe was sincere in his hope for further support for the game. But, no: Ron Edwards (2002) analysed 'fantasy heartbreakers' like Forge as doomed from the start by economic realities as much as by their shortcomings as products in a crowded marketplace. I'm glad, though, that Forge got this far and that Mark Kibbe was able to deliver his RPG vision. There is much to commend it, but it illustrates an important lesson in creativity: focus. Kibbe never seemed to grasp what was distinctive about his game or his setting. Forge clearly began life as a post-D&D homebrew that reached an unusual level of sophistication and completion. Kibbe himself moved away from conventional dungeons and monster-baiting, in favour of more thoughtful scenarios. His setting moved away from a barbaric post-holocaust world to a civilised but precarious frontier, with hardy colonists carving out their prosperity in the midst of a vast wilderness. Yet he failed to capitalise on these features. The Church of Enigwa, which goes around burning wizards as infidels ... a world where the gods have been judged and condemned .... a society built around trade routes and trade wars ... a system of travel documents, official permits and bureaucratic paperwork ... guilds and thieves rather than monsters and demons ... This is not like a standard Fantasy RPG setting, yet all this stuff is hidden away in the margins or must be inferred by a diligent reader. There's a good campaign to be had in Juravia, something distinctive and distinctively American, but you feel that, even at the end of the product line, designer Mark Kibbe hasn't quite figured out what it is yet.

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed