|

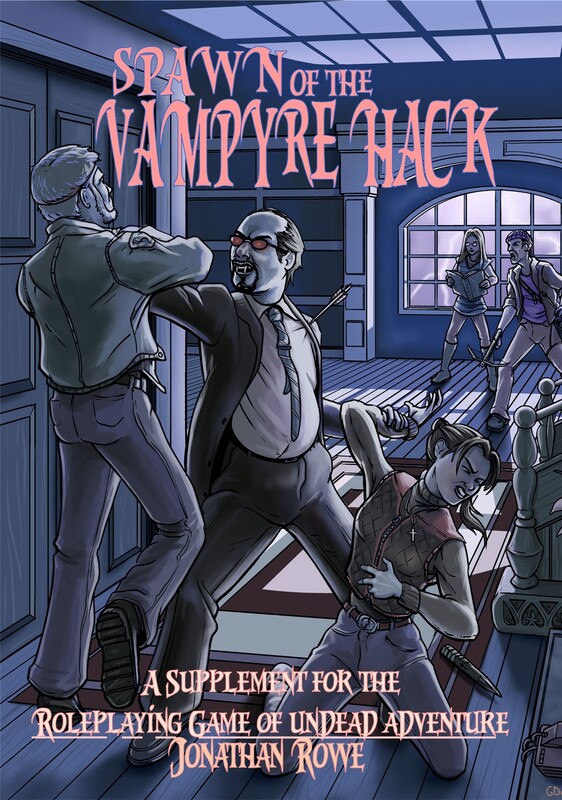

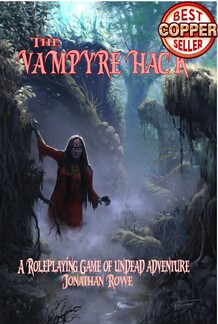

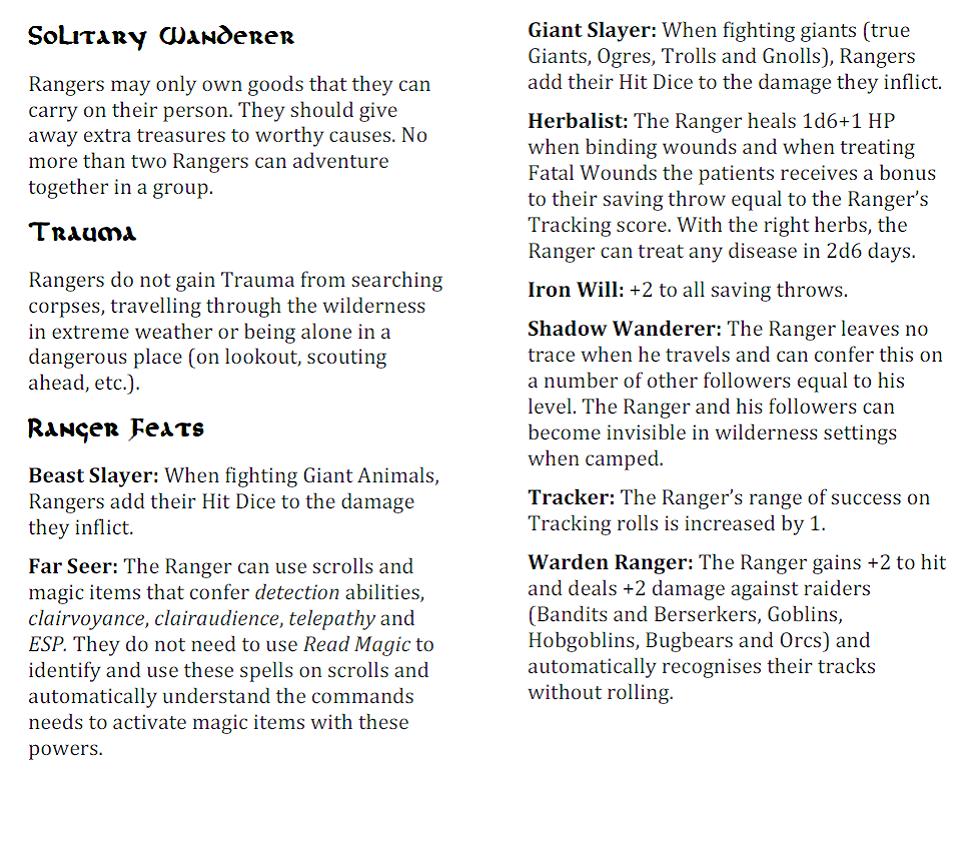

Hot on the heels of The Vampyre Hack (see blogs passim, such as here) comes its unholy spawn, a rather dense supplement covering mortals and almost-mortals that serve, traffic with, and hunt down the undead. The dynamic cover is ‘All Hope Is Lost’ © Gary Dupuis. The book is available as PDF from drivethrurpg or physical copies from Amazon. Like most sprawling endeavours, this book started as a modest project to provide some rules for human Witch-hunters, either as more developed antagonists or as Player Characters battling against NPC vampyres. But then I added in more detailed rules on the Familiars that serve vampyres ... and then I thought I ought to cover the half-vampyric Dhampirs who are born with vampyre blood in them ... well, I got carried away. I'll take this promotional blog as a chance to indulge in a bit more critical nostalgia about Vampire: the Masquerade in the 1990s, the directions it took, and the various ways I've stuck with or departed from that template. Ghouls Just Wanna Have FunGhouls were there in 1991, in the original V:tM rules set. They are humans given a sort of provisional immortality and a bit of a strength boost by feeding on vampire blood. If the immortality and the strength isn't enough of a motivation, they're usually victims of the Blood Bond, making them devoted slaves of the vampire that feeds them. You can use the background dots in Retainers to represent these guards and flunkies, a convention which established an anonymity about them which endured right through the product line. Subsequent expansions developed the vampire Clans massively, but never really got to grips with Ghouls, who surely outnumber actual vampires by orders of magnitude and were pretty essential for their functioning and safety. Ghouls: Fatal Addiction came along in 1997 to set things straight. The book was part of the Year of the Ally series, focusing on the sidekicks in all the World of Darkness games at that time. Its cover and interior art drew heavily on BDSM themes, making it feel like a release from the company's Black Dog imprint, specialising in mature themes. It's been replaced by similar supplements for later editions, but the original is still on driverthru in all its kinky glory. Ghouls:FA leans pretty hard into the idea of Ghoul-dom as soul-crushing addiction and debasing submission. The supplement actually has a lot of neat rules for Ghoul characters of different sorts, including settling lots of questions about the nuts and bolts of feeding on vampire blood and the effects of withdrawal. The only catch is that the theme of sexual fetish running through the art and a lot of the fluff fiction rather distracts from its purpose. What was needed was a book looking at Ghouls across the vampire world and the uses different Clans find for them. Instead, there's a rather relentless focus on sexual and kinky motivations, to the point of making you wonder whether the authors are venting some personal issues. Guy Davis' art is GREAT, but if your PC's Ghoul is a snooty cordon bleu chef or a garrulous taxi driver named Frank, you might wonder what all the leather and rubber is for. Making the Revenant Relevant & ResonantWhile the poor old Ghouls were being debased, another concept was emerging from the margins of the World of Darkness. A rather controversial supplement called Dirty Secrets of the Black Hand (1994) introduced the idea of Revenants, which are humans born to Ghoul parents and granted long life and supernatural powers by the vampire blood in their veins. Yes, 'Revenants' is a bit of a stupid word for this sort of creature, since they haven't died and come back to life again. It's an odd misstep for White Wolf, who were normally so inspired in their naming conventions. But then, DSofBH is full of missteps and Revenants are among the few concepts introduced in that book to be adopted widely. DSotBH introduced three Revenant families bred by the Tzimisce vampires to serve the Black Hand: Enrathi child-snatchers, Marijava spies, and Rafastio witches. Ghouls:FA introduced a few more that serve the wider Sabbat: monster-wrangling Bratoviches, mortal-manipulating Grimaldis, scholarly Obertus, and party animal Zantosas. Other splatbooks, especially for Tzimisce, added many more - and the Tremere get their own Revenants, the wizardly Ducheski. There's no doubt that Revenants are a significant addition to the World of Darkness setting, shifting it away from 'real world with vampires in it' into a dystopia infested with half-human collaborators practising abduction, murder, and exploitation on a grand scale. Your mileage probably varies with this sort of thing. It's part of the mid-'90s 'Vampions' phase of the game where everything got lurid and nihilistic and the 1st edition's rather gentle and melancholic moral tone was binned. The designers seemed a bit ambivalent about Revenants. Perhaps aware of how their presence in a game could destabilise the power politics of the World of Darkness, they took pains to point out how most Revenant families survived only in remote parts of the world (this was the '90s: Eastern Europe or Central Asia might as well have been Oz) or worked solely for the Tzimisce, with their parochial Balkan obsessions. Vampire Hunting: what a difference a decade makesIn 1992 there was a delightful supplement for 1st edition V:tM called The Hunters Hunted which took the idea of mortal vampire hunters and turned them into player character options. Covers are so revealing, don't you think? Janet Aulisio's cover art for the 1992 original is full of atmosphere, as a geeky squad of amateur hunters peer by flashlight into a cellar, clutching their tomes of lore, stakes and a mallet. What's down there? Dare they descend? Will they ever come out again? By contrast the 2013 edition shows a bunch of dudes straight up staking a vampire on the floor. Something subtle has been lost along the way ... Hunters Hunted is maligned as a flimsy document that lacks ambition. It sets out motives for vampire hunting, gives some equipment and a few templates, and describes some organisations that hunt vampires, like the governmental NSA and CDC and the occultist Arcanum. It introduced the idea of 'Numina' or minor magical gifts, including the power of True Faith hinted at in the original rulebook and paths of 'Thaumaturgy' for mortals that were later re-branded as Hedge Magic. The main thing the book offers is a ton of theme and sensibility. Predating the cosmic scope of the later World of Darkness, it describes a setting in which vampires are the main - or possibly the only - supernatural threat and Hunters go after them armed with chutzpah and solid brass balls and not much else. Contrast 1999's release, with Hunters getting their own standalone game Hunter: the Reckoning. By the end of the '90s, the night has become a crowded place and Power Creep is well under way. Vampires are by now assisted by Ghouls in gimp suits and veritable armies of Revenants, not to mention all those Level 6+ Disciplines. New-look Hunters are called 'the Imbued' and they are honest-to-goodness superheroes with magic powers. Yup, that's where the game line ended up. So, what went wrong?In a sense, nothing went wrong. Vampire: the Masquerade was incredibly successful. It went from a little indie project to a world straddling publishing phenomenon, with spin off TV shows, card games, and video games. It beefed up, put on some muscle, lost its shyness, gained some swagger. The original themes of moral struggle and redemption got sidelined, in favour of horror, epic sweep, and Nietzschean bombast. It was following the fans in all of this. People got the game they wanted, which wasn't quite the same as they game they were originally pitched. The 1st edition rules had a story serialised in the illustrations, in which a a family man turned into a vampire by a seductive lover at a 'Midnight Michelangelo' exhibit finds the resolve to confront his creator and win back his humanity. Later editions abandoned this sort of sentimentality, in favour of torture-porn dominatrices and inhuman spiritual paths. Each to their own, but the later iterations of Vampire struck me as coarser than its first expression, for all that the setting became crowded, louder, more violent, and more dazzlingly diverse. There's a metaphor there, for postmodernism, or growing up, or something. Expanding the Vampyre HackThis book took a lot of writing. The Vampyre Hack adopted the framework of Matthew Skail's excellent Blood Hack and adapted it to thinly-disguised pastiches of the 'Classic 7' vampire clans from V:tM. It pretty much wrote itself. Bride of the Vampyre Hack was a bit more innovative, playing fast and loose with the independent and Sabbat Clans introduced in later V:tM supplements. More novelties required more thought, but the templates were still there to lean on. Both are on drivethru (click images for links) and as a bundle, while there's a complete physical edition called Tomb of the Vampyre Hack on Amazon. Spawn of the Vampyre Hack goes a lot further from the source material. First off all, there's a bunch of rules for mortals. Mortals can only get to 5th Level, they have to choose between increasing their Usage Dice or getting useful Talents, they suffer Hunger and Exhaustion and more formidable Out of Action (OofA) penalties. They're flimsy. Familiars Let's start with Familiars (aka Ghouls). In V:tM, any vampire can turn a human into a Ghoul. In Vampyre Hack, you need a Greater Blood Gift to do this or a Rank 2 Goetic Spell. Starting characters could recruit a single Familiar via a Lesser Blood Gift - and the lordly Sangrali can create Familiars for free as their class ability - but Familiars are generally rarer and a bit more precious as a commodity. They are an investment. You're also restricted to managing no more than one Familiar per level you have (twice that for Sangrali) which makes it important to choose them carefully. There will still be vampyres out there whose Familiars are sex toys, but the rules make you choose between such self-indulgence and more practical concerns. Of course, any vampyre can bind mortals to him using the Sanguine Fetter (i.e. blood bond) but Fettered mortals don't become Familiars: they still age, they don't get super powers, it's just not as useful. Out of your general pool (or Paddock) of Familiars, one is your adjutant, known as your Grimalkin. This Familiar is a cut above the rest: you've imbued her with your essence, she goes up in levels with you and acquires more powerful Blood Gifts. Grimalkins get the player character treatment. A Talent available to some Familiars is Unfettered, which weakens the Sanguine Fetter, allowing PC Grimalkins a measure of independence. It also explains the existence of Gallowglasses, who are Rogue Familiars struggling to preserve themselves by working for payment in vampyre blood. Alchemical Talents enable them to avoid the Sanguine Fetter by making blood donations last longer or even removing the enslaving effects. Familiars at 1st and 2nd Level can hold their own against a vampyre of the same level, but even with the extra powers that kick in at 3rd-5th Level, vampyres start to pull away. Unfamiliars Then there are the other Familiars that don't have it so easy. Blajini are the malformed creatures that higher level Zoltan vampyres create with their flesh-warping. They struggle to pass for human, but at least they aren't usually Fettered. Strega vampyres can't create Familiars with their blood and few of them know Goetic magic, but they summon ghosts and place them into corpses and their Zombies serve many of the same functions. Of course, the ghost has its own memories, attachments, and agenda, and the rules encourage Zombies to pursue a side hustle of dealing with the issues they died without fixing. Chorazin vampyres use Goetia to create Golems and Flesh Golems make tank-y alternatives to Familiars. Once again, the brain sourced for the Golem preserves fragmentary memories and desires from when it was alive, which PC Golems can fulfil when their masters aren't watching. Un-persons are the soulless victims of the Unlife that higher level Rakasha vampyres manipulate. It's not much fun playing one of these, but how about playing all of them? The Bhuta is the collective intelligence of the Un-persons serving a vampyre and it switches its consciousness between bodies in order to pursue its Weird - an alien agenda that the vampyre had better not find out about. Unfamiliars are an exotic option for experienced roleplayers, especially as they are hiding not just from humanity, but concealing their independence and intentions from their own vampyre masters. Dhampirs Dhampirs are what Revenants should have been called (though, to be fair, the World of Darkness applies the term to a different type of creature). Since Familiars and Unfamiliars can't beget life, something very odd has to happen for one of them to conceive a child who will be born with vampyre blood. I set about concocting reasons why this might happen. For example, the Ajakavas have their foetal soul replaced by a ghost thanks to necromancer and are born 'possessed' while the Grosvenors are descended from werewolves whose vitality overcomes the poisonous vampyre blood in their parent's body; Czernobogi are made fertile by a cthonic ritual in a sacred grotto while Harpagons have literally made a deal with a devil; the all-female Nafarroa have used their witchcraft to remain fruitful while the alchemist Darzis use potions. The Fae-touched Duvaliers, werecat Nunda, and leprous Jahangirs have similar backstories. Dhampirs are split between the Vassal Lineages who work directly for vampyres and the Mercenary Lineages who manage a degree of independence, selling their services without committing themselves. What I'm trying to do here is build the idea of Dhampirs existing independently (albeit very contingently) from vampyres. Part way between humans and the undead, they're a 'third force' in the setting, albeit a weak and disunited one. They function as powerful enforcers for the vampyric 'hegemon', but also potential allies PCs can go to that won't automatically turn the in to the Elders. They're not liminal figures like V:tM's Revenants, but they're independent and unreliable, and as likely to be the targets of vampyric plots as the instruments employed by them.. Witch-hunters Here are the Hunters that this supplement was supposed to be all about in the first place. There's a bunch of mortal character classes, like Clergy, Psychics, Shamans, Techies, and Special Agents that cover the broad templates from Hunters Hunted. The Fanatics and Paragons are a bit more like the 'Imbued' from Hunter: the Reckoning, since they are mortals whose life-changing traumas or supernatural benefactors confer powerful abilities. The Security Usage Die from Vampyre Hack is reinterpreted for hunting vampyres. You have to force the vampyre to roll Security by fulfilling investigative challenges until it shrinks and fully exhausts: then you've got him at your mercy. Yes, it'a a pretty clumsy system, but most of the time Players will roleplay their way to the showdown before the Die gets exhausted, which means a trap or ambush is in store. What has Spawn of the Vampyre Hack got goin' on?The Vampyre Hack is my part-apologetic, part-wistful, part-resentful love letter to Vampire: the Masquerade. Partly, it's a fun project to reinterpret the clunky handfuls-of-dice 'Storyteller System' into a simpler, more intuitive D&D-style game. Partly, it's a way to go back to vampire RPGs without the wider setting that V:tM acquired in the '90s, much of which I took issue with. It's a chance to approach the clans, lore, and institutions, like ghouls and revenants, afresh, saying to myself 'How would you rather this had developed?' Partly, it's an original creation, saying, 'Isn't this a novel and intriguing way of doing vampire tribes and their various undead and semi-undead apparatchiks?' TL:DR, Spawn of the Vampyre Hack concludes this project for the moment. I've got a scenario in mind and a solo rules set in development, but the old vampire itch has been scratched. If you play Vampyre Hack, with or without its Spawn, let me know how it goes! Next on the list, The Full Moon Hack, for werewolves and their ilk.

0 Comments

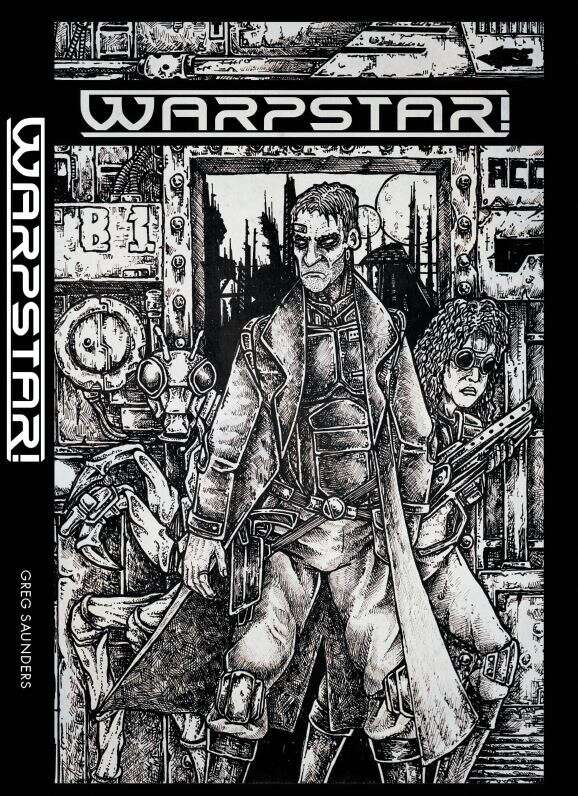

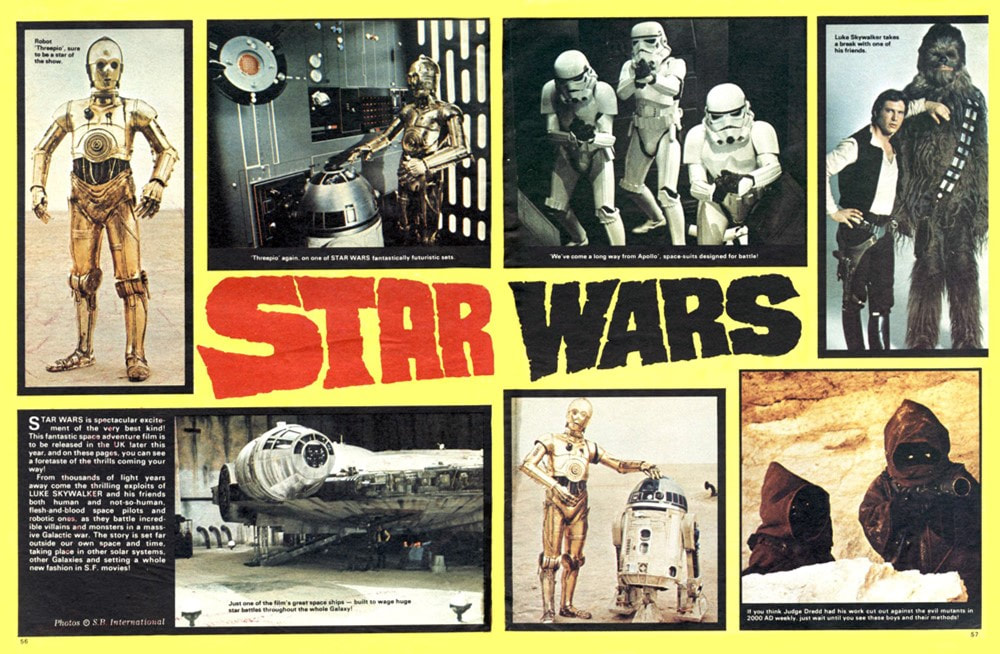

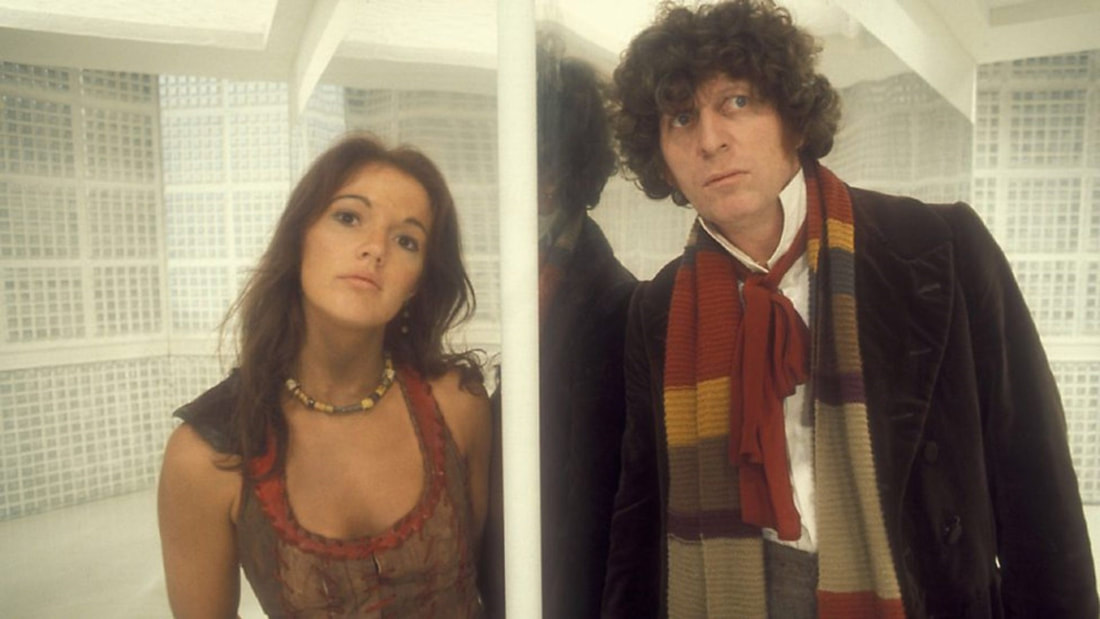

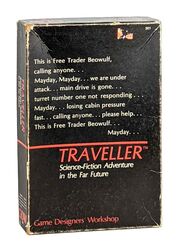

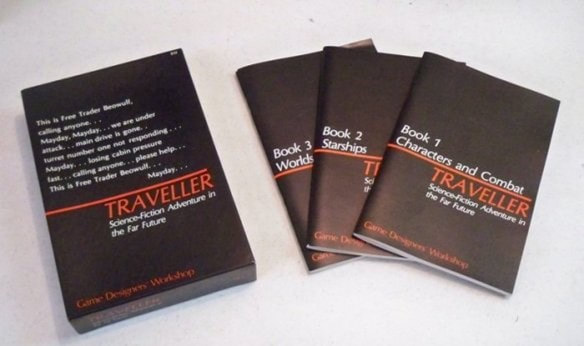

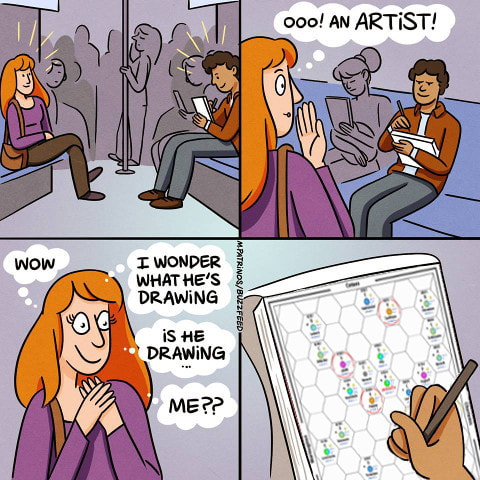

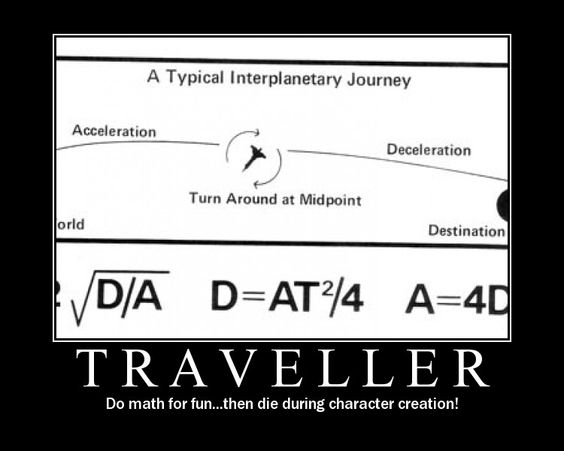

Before I talk about the Warpstar! RPG by Greg Saunders, I want to take a long route around. I'm a Star Wars kid. I was 10 when Star Wars premiered in the UK and went to see it on my 11th birthday. I was blown away. Obviously, I had to own the action miniatures, a cardboard Death Star, the board game, the comics and a collection of those strange cards you bought with bubblegum (which I detested). I'd been groomed for Star Wars by the UK comic 2000AD which had appeared earlier in 1977 and thrilled me with dinosaur hunting time-travellers, Dan Dare and, of course, Judge Dredd. The 2000AD Summer Special had heralded the arrival of Star Wars with a centre splash page that conveyed no idea of who the hero was or who the baddies were (Jawas, perhaps?) but the mysterious images pierced my soul with their distinctive blend of space romance. The 1977 2000AD Summer Special: the caption for Han Solo and Chewbacca reads 'Luke Skywalker takes a break with one of his friends.' After that, I loved Sci Fi. I'd loved Science Fiction before, of course. I adored Doctor Who and the Tomorrow People on TV and was an avid fan of Space 1999: the distinctive Eagle spaceships from that show were a treasure childhood toy along with an Interceptor from the earlier Gerry Anderson show, U.F.O.. Doctor Who acquired a, err, charming new companion in 1977, but Tomorrow People had the haunting and enigmatic opening sequence and a stranger and more provocative concept. Best. Toys. Ever. My first ever memory of watching TV is the episode of Star Trek where Kirk fights Spock with weird weapons in an arena: I was, I think, 3 or 4. Are you hearing the music in your head? But Star Wars involved a sort of commitment to glorious starscapes, roiling planetary surfaces, lasers in the darkness and gleaming battle armour. The odd thing is that, within a year of watching Star Wars for the first time, I was playing D&D. Roleplaying quickly dovetailed back into science fiction, with the Gamma World RPG and Traveller in its iconic black box. Age cannot wither her: there will probably never be a RPG set this ... beautiful Yet science fiction roleplaying just never captured my imagination. Gamma World was a lark with its gun-wielding mutant bunnies, but it just wasn't serious the way D&D could be. What about Traveller? Well, I certainly tried it. Who couldn't love the sleek modernism of the three-book box set, the cool black-and-red iconography, the tantalising mayday from Free Trader Beowulf ... Traveller: Science-Fiction Adventure in the Far Future was clearly a serious game set in a serious universe. I spent merry hours rolling up planets and populating my own sector maps. Yes, and not just sector maps, but rolling up animals and random encounter tables for those planets, then rolling up all sorts of retired Marines and cashiered Naval Officers ... Notoriously, the process of rolling up a Traveller character could result in dying during background history. Traveller invites you to create a 40- or 50-something PC who has already had a proper career in the military or in politics but then decides, in a ludicrous mid-life crisis, to go gallivanting round the universe getting into hare-brained scrapes with a bunch of strangers. As a roleplaying proposition, I found it a bit of a stretch back in my teens. Now that I'm the same age as those characters, it's no clearer to me what Traveller PCs think they're up to. So, I rarely played Traveller and when I did, the results were underwhelming. Traveller just never seemed to catch fire. There wasn't, for me, a story that was dying to be told and needing Traveller as its idiom. There was just a lot of aimless wandering in space ... heists ... bounties ... patrons in space bars ... the cost of repairing ships ... Twilight's Peak (1980) was a striking scenario but I just couldn't sell it to my players because, well, I wasn't sold on it myself despite Andy Slack's glowing review in White Dwarf #24 ('This is how Traveller should be. Buy it.'). Back to the dungeon I went and never really looked back at SF RPGs. (My) Problems with SF RoleplayingPart of it was just maturity. Traveller isn't as easy for teenagers to switch on to as D&D. In a fantasy RPG there are standard tropes: you arrive in a village, you go to the inn, some ageing peasant tells you of strange goings on at the ruined keep and the disappearance of the miller's daughter, off you go to clean the site out of kobolds and rescue the maiden. OK, you could substitute 'planet' for village and 'spaceport bar' for tavern and, I suppose, a 'disused orbital space station' and a 'missing corporate CEO' (female, if you insist). But immediately , questions intrude. What sort of planet? What sort of spaceport? What exactly is this orbital facility? Which corporation? Why isn't anyone else dealing with this? You might say that answering those questions is precisely what makes for designing a good adventure - and you'd be right. But my problems were closer to home. D&D offered easy access because everyone knows what a medieval village, tavern and ruined keep would be like - but everything needs thinking about in a SF RPG and nothing can be assumed. Or so it seemed to me at the time. In any event, Traveller seemed to set a high entry bar in terms of conceptualising and preparing the scenario, while not offering particularly clear hooks. You see, Traveller was basically the Nineteen Seventies In Space - and a rather banal, suburban take on the Seventies at that. Traveller didn't have laser swords, space wizards, godlike AIs or matter transport beams, let alone smart drugs, cyber-enhancement or netrunning. There was a sort of austerity to Traveller: computers were big box-y things, laser pistols were inferior to conventional slug-throwers in most contexts, the PCs were middle aged, psionics were rare, aliens scarce. When Traveller's official setting introduced the Aslan lion-people and Vargr dog-people, they were hardly compelling. Gentle reader, you might be tearing your hair out. Why didn't I just add those things in if I wanted them so badly? Of course, I could have. But I think I was as enthralled to Traveller's severe aesthetic as I was repelled by it. The game seemed to demand to be taken on its own high-minded terms. It would seem ... somehow, I know not how ... clumsy to foist lightsabres, transmat beams and cybermen onto Traveller. It would have been indelicate. Jejeune. I was too much a roleplaying snob to let myself have fun. Hey, Idiot: why not play Star Wars? A friend has reminded me that West End Games did a fantastic Star Wars RPG back in the '80s. I remember playing it, now that my memory is jogged. I owned the d20 Star Wars and Star Trek RPGs way back when as well. But ... I don't know. I've never really cared for tie-in games. I'm not bothered about the Dune, Blade Runner or Firefly RPGs either. Maybe it's my snobbery again, but I wanted a RPG that enabled me to create something like Star Wars or Firefly - without roleplaying in the official universe of those franchises. For whatever weird reason, I've been looking for a SF RPG that would make me want to create my own science fiction, not inhabit someone else's. OSR To The Rescue !My rehabilitation in SF RPG was a long time coming. I contrived to miss out on the genuinely up-to-date SF RPGs of the 1980s (Cyberpunk, SLA Industries) or the loony SF mash-ups of the '90s (Rifts, TORG). I somehow managed to avoid Star Frontiers, which offered actual D&D in space and would surely have disabused me of the hurtful notion that SF roleplaying had to be particularly clever or sophisticated. 'The Playable One' seemed like a direct dig at maths-heavy Traveller. There's a lovely retrospective of Star Frontiers but by 1980 I'd been scared off by Traveller and stuck to my fantasy furrow. I never really looked at SF RPGs again until quite recently, when the OSR trend for adapting original D&D led me first to White Box, then White Box spin-offs like Eldritch Tales (last post) then to James M Spahn's White Star. White Star comes as a perfectly-serviceable basic rules and an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink Galaxy Edition (which you might as well go for if you're getting the PDF since the digital versions cost the same). White Star is a beautifully-presented adaptation of White Box style D&D into a SF idiom. It is also completely shameless about porting in Star Knights with their laser swords, alien brutes, computer-hacking cyphers, cyborg, superheroes, mechas and a host of other stereotypes to create a broad palette you can pick and choose from. I really wish I'd found something like this in my '80s teens. If White Star has a problem, it's perhaps that it's too broad. With every science fiction and science fantasy trope on offer, it risks losing the idiosyncracy that intrigued me in Traveller: the offer to roleplay in a highly distinctive universe. With White Star, the problem isn't all the stuff you have to add in; it's the stuff you have to take out. Interlude: Lady Blackbird and Scum & VillainyDuring the first Lockdown there was an opportunity to roleplay with friends via Zoom and we tried out Lady Blackbird by Jon Harper: it's a free mini-RPG and you can find it here. We also played another of Harper's games, the excellent Blades In The Dark. Blades has a sister product called Scum & Villainy and I sourced a copy of that in my newfound enthusiasm for space romance. Lady Blackbird is a 15-page RPG with a set of pre-generated characters who start off as prisoners on board the imperial cruiser Hand of Sorrow. The rag-tag group have to escape and get back to their ship, the Owl. The group includes a space princess fleeing an arranged marriage, her bodyguard, a romantic space captain and his quirky crew. The universe is the 'Wild Blue' (shattered worlds around a dimming star), with breathable space, space squids, space goblins, space magic. It plays out like a Saturday morning matinee. It's steampunk Star Wars. It's great. Blades in the Dark is a bigger project, but Scum & Villainy grounds its wide-open RPG system in a manageable small corner of space called the Procyon Sector: four out-of-the-way solar systems linked by interstellar gates but somewhat cut off from the vast galactic empire. Here's a setting with space mystics, alien AIs, sci-fi religions, glamorous guilds of space-thieves, very much space fantasy. So, Star Wars again (as the title alludes). John Harper has certainly won me back to SF RPGs, but of a distinctive genre: space romance. His trick is to set the action in a very localised part of a very particular sort of SF universe: one with a lot of the accoutrements of fantasy roleplaying. The catch is, you really need 5 players to run Lady Blackbird (and it's a one-shot); Scum & Villainy is designed for campaign play, but it's quite demanding. Warpstar To The Rescue (and about time too!)Recently I came across Greg Saunders' fantasy RPG Warlock! (reviewed here) and was impressed by its artfully minimalist rules and striking tone. I quickly discovered that Warlock! has a sister product: SF RPG Warpstar! (see what they did there? both games begin with war-! and end with -!). Could this be the game that properly lures me back to SF? Warpstar! is very much Warlock! re-skinned for SF. You have just two stats (Stamina and Luck) and a set of 32 skills you add to a d20 roll, trying to hit 20+ or just beat your opponent. These skills start at 4, 5 or 6 but five of them are career-specific and you have 10 extra points to split between them, to a maximum of 10 or 12. Some are generic skills (spot, Stealth), some familiar from the fantasy game (Short Blade, sleight of Hand) and some are new to the SF setting (Astronav, Ship's Gunner, Zero-G, etc). One, Warp Focus, lets you do 'magic.' The 24 careers cover the spectrum of SF tropes. Some are professions (Bounty Hunter, Diplomat and I suppose Pirate and Gambler) but others are more like archetypes (Street Kid, Rebel) and one, Warp-Touched, is a space wizard. As well as boosted skills, each career comes with a couple of tables to roll (or choose) your background and quirky details of your motivations, past escapades, enemies made and reputation earned. As with Warlock!, there is a ton of imagination in these tables, which accomplish more world-building than an entire chapter of setting, and a slightly seedy tone that Greg Saunders delights in. Characters can use experience to switch careers, broadening their repertoires, and gain access to Advanced Careers if they want to push their skills into the teens. In a variation on the Warlock! template, everybody starts with a randomly-rolled Talent, to give PCs a little more heroic oompf than the down-at-heel misfits of Warlock! ever enjoyed. Combat is a standard skill test, but hand-to-hand combat involves an opposed roll, trying to roll higher than your opponent. The risk of launching an attack but coming away as the one who takes the damage should make players cautious about resorting to violence. Once Stamina hits zero, you roll for lasting Criticals, the worst of which kill you outright. With PCs boasting Stamina scores in the teens or low 20s and weapons doing damage ranging from a d6 (knives, etc) to 2d6+4 (pulse guns), you can afford to get hit once. but after that you consider retreating, which carries no penalty. The intention is that combat usually goes to first blood, then NPCs (and wise PCs) back off and try a different approach. Stamina is regained rapidly - you get half of it back after a brief rest, all of it after a long rest. Magic enters the game because of the Warp Space that ships use to cross interstellar distances. This isn't the clean and clinical hyperspace of Star Wars; no, it's the chaos-realm of Warhammer 40K and anyone exposed to it risks being mutated, but one such mutation is the acquisition of spell-like powers called Glyphs. As with Warlock!, spells/glyphs are physical things that an aspiring magus has to hunt down, bargain for or steal from other practitioners. The main addition to the game is the addition of space ships and ship combat. It's assumed each PC group gets their own space ship and you can roll or choose from a set of 6, each with a distinctive design and aesthetic: from the elegant D'Aubigny Envoy Cruiser to the tough, fast but unfashionable Kilos Star Hauler. Spaceship combat is handled just like personal combat. Ships have Stamina (called Structure), armour, built-in weapons that deal damage in a similar range to (but great scale than) personal weapons. It's a clean, intuitive system that once again encourages brief skirmishes then running away once someone takes damage. The setting is a vast Galactic Empire known as the Chorus. This is ruled by fractious noble houses who, in a clear nod to Dune, achieve an almost-immortality through using the space-drug Cadence, the source of which is known only to the supreme Autarch. Other factions include the military Hegemony, the unscrupulous Merchant Combine and the arcane Warp Consortium whose possession of weird technology makes them, in effect, a guild of sorcerers. A bestiary includes some oddball aliens, some of which (the Fruiting Dead and Borg-alike Nodes) imply cosmic horror, but many of which seem to delight in upsetting expectations, such as the troll-like Jondo who are actually placid and philosophical or the hideous dog-monster Borrs who are actually deeply cultured. Warp Entities allow for the inclusion of space dragons, space vampires and space demon-gods, according to taste. So, is it any good? Yes. Warpstar! is quick, clean and intuitive - as you'd expect from an adaptation of an already-solid game like Warlock!. The setting is highly serviceable while being vague enough to customise. The character careers offer lots of hints for your first few scenarios. Nobody dies in character generation. Some features are 'baked in' to the rules. There's space-magic, for example. You could prise it out, I suppose, or recast it as psionics if you are allergic to fantasy in your SF (although references to Warp mutations run all through the rules and setting). The combat system, as noted, does tend to impose a cautious, scaredy-bully style of play, where antagonists shoot or stab each other once, then down their weapons and negotiate. The skill system means that PCs tend to succeed between a third to half the time, which is a bit low for a truly swashbuckling game, a bit high for gritty techno-realism. But I like these baked-in features. They give the game some character that seemed to be missing in White Star, for example. I could see myself using Warpstar! to scratch the itch for SF one-shots - or to adapt Traveller scenarios (such as used to feature in White Dwarf of old) into a slightly more space operatic idiom. I've also acquired the Omoron sourcebook, which is a Warpstar! detailed setting: a peculiar star cluster that's a bit like the Procyon Sector in Scum & Villainy. It features a couple of scenarios, but I'll not mention them until I've run them on my gaming group. Omoron (and several other sourcebooks for Warpstar!) is available from drivethrurpg The only criticism I can make of Warpstar! is the price. The rules are available as PDF and hardback. The PDF is £9 which isn't exactly cheap, but you're getting a solid game and a lot of setting ideas for your money. The hardback is a stonking £33. Why so expensive? Well, it's because this is the premium colour price point. Is there a lot of colour in the rules? No, barely any - but Greg Saunders explains "the premium colour option has been chosen for the print version as it represents a much better quality of paper with an improved look and feel." I bit the bullet and invested in a physical edition because I find it hard to use PDF rules sets in play; I can attest that the paper is very good quality, the book looks clean and clear and, well, very SF, so that's a big tick for Artistic Standards. But it has to be said the book really doesn't need this treatment, especially as the art style throughout aims for the same scuzzy 1980s-fanzine vibe that informed Warlock! I mean, it looks great, but it would marry very nicely with coarser paper and lower resolution. You can't help wishing there was a nice cheap non-premium edition, or even better a non-premium softback. If you could buy a physical copy of Warpstar! for, say, £10-15, I'd cheerfully treat my group to 'players copies' to build commitment and speed up character creation. Warpstar! hits my sweet spot. It delivers space romance (which I think is my preferred genre, rather than Hard SF) with a simple but distinctive rules set. It's got theme and imagination running through it. It posits player characters who are quirky and distinctive, but of less-than-heroic stature. It will hit the gaming table a few times over the next few months. I'll review the Omoron campaign book when it does.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, For great poems about (possibly) haunted houses, there's Poe and Walter De La Mare's The Listeners, but Poe describes the situation where the ghost is trying to get in - which is the theme of the second scenario for The Ghost Hack. UPON A MIDNIGHT DREARY underwent a playtest last week and here's the session report. Of course, massive SPOILERS ahead. Evocative cover art by Bob Greyvenstein. Interior art (used below) is copyright Steve Miller (2015). Click image to link to drivethrurpg. The scenario played out over two sessions, with a shifting cast of PCs:

After the events of HELL HATH NO FURY, the PCs are all second level and Joshua Pflint has a wightblade sword (for a while longer anyway). Mortal Coils The story begins (as they usually do) with the PC ghosts checking on their Mortal Coils. Lexi is furious to find a new manager at her beloved bar, The Crash Lounge, has installed a massive TV screen to play noisy sports to customers. She uses Ghostly Caress to change the password on the satellite box, locking it down. Oscar visits his wife, who has moved the children to a new home in an old signalman's house beside an abandoned railway line. There's a crisis when his son Dale goes missing. Oscar finds the boy in the railway cutting, playing safely and watched over by another ghost. This ghost is an old signalman and introduces himself as Edwyn Sullivan - or 'Sully'. He manifests in order to return Dale to his mother and asks in return that Oscar helps him. Sully haunts the old Trevalyan House, but a team of Ghost Hunters has moved into it, using salt to lock Sully out and trap his ghostly wife inside. Oscar agrees to find a way into the House and rescue the ghost trapped inside. In fact, 'Sully' is really evil Dr Reinhardt, a dead serial killer, using Apparition to take another form. The bit about the Ghost Hunters and his wife is true. He hasn't mentioned the cellar full of ghostly victims he and his wife have been torturing for half a century, now all dangerous Wights. Who ya gonna call? Oscar assembles fellow-ghosts Gregg and Lexi to visit the Trevalyan House. They can see it's been recently renovated but then abandoned. A crazy old lady sticks up posters warning people to STAY AWAY - EVIL LIVES HERE! A mysterious blonde girl takes photographs of the building until the old lady chases her away. The PC ghosts decide to enter. The two mortals are important NPCs. The crazy old lady is Kathleen Dawson who escaped from the Trevalyan House 50 years ago when she was just a young woman, bringing the Reinhardts' murder spree to an end. The younger woman is Michelle 'Misty' Quint, a wannabe serial-killer under the spell of Dr Reinhardt's evil ghost. The players debate for a while and decide it would be best to ignore these blatant plot-hooks. The building has been warded with salt, making it hard to pass through the walls. Gregg enters the back pantry and finds one of the Ghost Hunters there, making lunch for the team. When Oscar joins him, they accidentally set of the EMF Meter the hunter is carrying. The young man lashes out with a wrought iron baton. These hunters are well-equipped to deal with ghosts! Oscar retreats out of the house but Gregg stays at a safe distance and observes. The hunter, Lloyd, is joined by an older man in an iron wheelchair. He is Fyodor Herzog and he has trapped a ghost in the kitchen, inside a circle of salt. Gregg notes with dismay that the trapped ghost is a feral Wight that bashes the kitchen table about in impotent rage. Herzog appears to be trying to interview the creature, as if he can actually hear it. More Wights are trapped in the cellar, including one who is a witch-like woman who seems to possess more rationality and wickedness than the others. The salt wards are salt crystals stuck to adhesive tape that the Hunters have slapped down across doorways and windows, making entire rooms impenetrable to ghosts. As starting characters, the PCs have relatively un-rotted souls (in game terms, their Grave Die is only a d6) so they can push through walls and doorways with effort - they have to make a CON test at a penalty. This creates a lot of anxiety as some PCs succeed and others fail, splitting up the group, while those who get inside worry about being able to get back out again. Lexi enters the study instead and finds the team leader, Greta, working on salt-based grenades. Staying clear of Greta's EMF Meter, Lexi reads Greta's notes on the house, learning about 18th century murders who laired here and a more recent spree of murders in the '70s. Greta, leader of the Ghost Hunters P.A. arrives and investigates the team's van. He discovers that the team is from The Ghost Society and has been recruited by the house's new owner, Jerome Maxwell-Goode, to investigate the strange goings-on in his new property. The Ghost Hunters are a complex bunch with dynamic interpersonal relationships. Lloyd's boyfriend Harvey is down in the cellar, being driven mad by the Wights. Herzog is having a nervous breakdown. A love triangle is leading to a violent resolution between Bernard, Lee and Anushika. A random encounter table mixes these developments up so that no two scenarios unfold in quite the same way. Trouble on the Tracks Lexi and Oscar decide to find and possess someone with the authority to enter the House. Lexi possesses a woman police officer, Chayan Kaur, and Oscar rides along unseen. Kaur is visiting a house where a child as gone missing and Oscar realises it is his own family. Dale has disappeared again and this time has not returned. Lexi guides PC Kaur and her partner PC Gill down the old railway track, to an abandoned siding where there is a big shed full of iron chains and an abandoned wagon. They realise that there are people locked inside the wagon, but the iron in the frame makes it impenetrable to ghosts. One prisoner is a ghost and he identifies himself as the real Edwyn Sullivan - the 'Sully' who introduced himself to Oscar was an imposter. The imposter reveals himself soon after as a vicious ghost with scalpel fingers who possesses PC Gill and attacks the PCs, along with his human accomplice, the blonde girl who swings an iron chain. Lexi knocks the evil ghost out of Gill by pushing him into the iron chains in the shed. She abandons Chayan's body to attack the ghost in person, but is outmatched. The ghost carves her up so badly she turns into a Wight herself and slips into Hades. Consumed by hatred, she visits her Mortal Coil and demonises the place, chasing out terrified staff and customers. Seeing what happened too Lexi, Oscar flees. The only good outcome is the PC Gill phones in a report to his superiors, so police will come to open up the wagon. Reinhardt's deadliness took the players by surprise. Lexi was unlocky to exhaust her Grave Die when she reached 0 HP but those are the breaks. Her Mortal Coil ended up shrinking by one dice step and she reformed amidst the wreckage she had caused, on 2 HP, feeling very traumatised. The survivor's story Gregg and P.A. have followed the crazy poster lady back to her cat-infested bungalow. They realise she's Kathleen Dawson and is obsessed with the Trevalyan House because she's the sole survivor of a string of murders there in the '60s and '70s by husband-and-wife serial killers Fitz and Beverley Reinhardt. As well as postering the house, she's pestering its new owner, Jerome Maxwell-Goode, but he is away on a cruise. The mysterious blonde woman arrives at the door and threatens Kathleen, telling her that Dr Reinhardt misses her and wants to see her again. She chases Kathleen into the kitchen where the old lady suffers a heart attack. Gregg manifests in his Charnel Form of a burning corpse and chases the young woman out of the house. Using ghostly caress, they contrive to get Kathleen her heart medication. Reinhardt was planning for Misty to kill Kathleen so he could chain her ghost up in chthonic fetters and take her to his wife Beverley as a gift. Now he's properly angry with the PCs for interfering. Dr Reinhardt Meeting together, the PCs conclude that the evil ghost who has engineered everything is Dr Reinhardt, the serial killer, and his wife must be the powerful Wight trapped in the cellar, which puts the Ghost Hunters in danger. They suspect the blonde woman is a murderess that Dr Reinhardt is mentoring to carry own his murderous legacy. They resolve to warn the Hunters and are joined by the Poltergeist Joshua Pflint. Return to Trevalyan House Back at the House, events have moved on. The Ghost Hunters have lost one of their number, Harvey, who disappeared investigating the cellar. The team's mechanic, Bernard, is working on drones to fly downstairs and investigate. Greta has nearly finished her salt bombs. Herzog has had a breakdown after psychic abuse from the Wights in the cellar. Tensions are brewing between Bernard and his girlfriend Anushika over team-mate Lee's attraction to her, which is clearly reciprocated. Beverley Reinhardt (in pre-Wight days) Oscar enters the kitchen and manifests to warn Bernard about the ghosts in the cellar. However, the team has no intention of leaving while team-mate Harvey is still missing. Greta (followed by Gregg) goes to try to shake Herzog out of his funk and Bernard (followed by Joshua) runs upstairs to find Lee and Anushika embracing. That produces a fight which sees Bernard badly beaten. Meanwhile, Lloyd, who is Harvey's lover, is lured into the cellar by Beverley Reinhardt, imitating Harvey's voice using manifest and apparition. Once down there, he is possessed by her and calls for help. Greta descends and the two of them drag Harvey up the steps, with the possessed Lloyd contriving to drop Harvey on the top step, breaking the salt ward there. Gregg decides to reveal himself to old Herzog, warning him about the Wights in the cellar. He advises Herzog to get to safety behind salt wards, ideally upstairs. However, he is too late to avert catastrophe. Herzog, the psychic The events in the house have triggered "the Crisis" - this is when the Ghost Hunters enter the cellar and unwittingly release the Wights. Catastrophe The rest of the team convenes in the kitchen to examine Harvey's body. Beverley Reinhardt steps out of Lloyd and summons her Wights up the stairs. Joshua uses his Poltergeist powers to snatch one of Greta's salt grenades and throw it into the cellar staircase, driving the Wights back. He attacks Beverley with his wightblade sword, but to no effect. Beverley demonises the room, shattering windows and flinging knives about, then blowing up the boiler. The humans are killed or traumatised in the carnage. Greta escapes but her salt grenades detonate, stunning her. Joshua resolves to hold the room against a small army of Wights. Spying on the outside, Oscar sees a taxi pull up. Out step the ghostly Dr Reinhardt and his mortal apprentice, Misty. The blonde girl starts to break upon the front door to the house with a crowbar. Misty, serial-killer apprentice Joshua escapes, dragging the unconscious Anushika out of the house and leaving the other hunters for dead. Greta drags Herzog to the front door, only for it to be opened by Misty, the young serial killer. She smashes Herzog's skull with an iron bar. Gregg tries to intervene by manifesting again in his burning-corpse form but Beverley appears and is far too strong, throwing him through the walls, gravely injured. Oscar contrives to get Greta to safety, by keening positive emotions into her and guiding her out through the study. At this point, the players realise they are overwhelmed. Four Wights would be a challenge on any day, but added in super-Wight Beverley, evil Doctor Reinhardt and Misty with her iron chain and the PC Ghosts realise they have to escape.. The Wights escape the house. They are the tortured spirits of the Reinhardts' old victims and now they desire only to find their own Mortal Coils and visit terrible sufferings on them. Dr Reinhardt is taken aback to see his wife is now a Wight. Beverley is furious to see he has been grooming a mortal protege. In a jealous rage, she attacks Misty and, gripped by a noble impulse, Reinhardt attacks his monstrous wife. They are lost to sight as the house burns down. Post Credit Scenes The PC Ghosts realise that the four Wight victims of the Reinhardts will race back to their Mortal Coils to visit unspeakable horrors on them. AS they are partly responsible for releasing them, the PCs stand to increase their own Grave Dice if they allow this to happen. So we have a follow-on scebnario: finding the Wights' Mortal Coils before the Wights do. In their favour, 50 years have passed since the Wights died in the cellar so the monsters will be a bit confused about where things are now. A closing scene has frail Kathleen Dawson recovering in hospital. She tells a kind nurse she is feeling much better and hopes to go home soon. This is greeted by cruel laughter from the patient in the next bed. The patient is Misty, recovering from her injuries in the Trevalyan House. She turns her burned face towards the terrified Kathleen and keeps laughing. Reflections The scenario unfolded beautifully. The PCs failed in the primary mission (defeating the Wights and Dr Reinhardt) but they did save a couple of Ghost Hunters from the House at the end. HELL HATH NO FURY had a linear plot that unfolded in a string of encounters in a more-or-less fixed order. Successful players were well-equipped for the final showdown. This scenario has a different structure. The House is a location with a cast of NPCs and monsters inside and a random encounter table dictating their interactions. The players can interact with this setting in any way they like. This makes UPON A MIDNIGHT DREARY far more open-ended. Exploring the Trevalyan House was delightfully tense, because of the difficulty with crossing the salt-wards separating each room. PCs were often in danger of finding themselves trapped in a room, unable to press on or retreat. Later, they found ways to disrupt some of the wards, making movement easier. But of course, easy movement for the PC ghosts also means easy movement for the horrid Wights. The players engaged with several plot strands (the wagon in the old railway siding, Kathleen Dawson, the history of the House, the team of Ghost Hunters) but never really pursued any of them. As a result, when the Crisis blew up, it caught the players on the back foot. Gregg (played by Karl) was only just revealing himself the the psychic Herzog. If that had happened earlier, things could have unfolded differently, with the Ghost Hunters as well-armed allies helping the PCs take on the Wights. As it turned out, the players found the least-optimal outcome and also the most alarming one, with the Wights rampaging through the House, the salt wards failing, the humans dying horribly... bad times. But also, good times. The players have a clear follow-on scenario to protect mortals from the spirits of as tragedy half a century ago now released and bearing down on unsuspecting families, former lovers, homes and grandchildren. Then there's Beverley Reinhardt, already established as a great villainess, and the merrily deranged Misty, the apprentice serial-killer, now operating without her beloved Dr Reinhardt guiding her murderous steps. The playtest threw up some valuable rules tweaks too, mostly to make the ghostly 'Crafts' more consistent in how they work. The 2.1 rules set on drivethrurpg incorporates these changes.

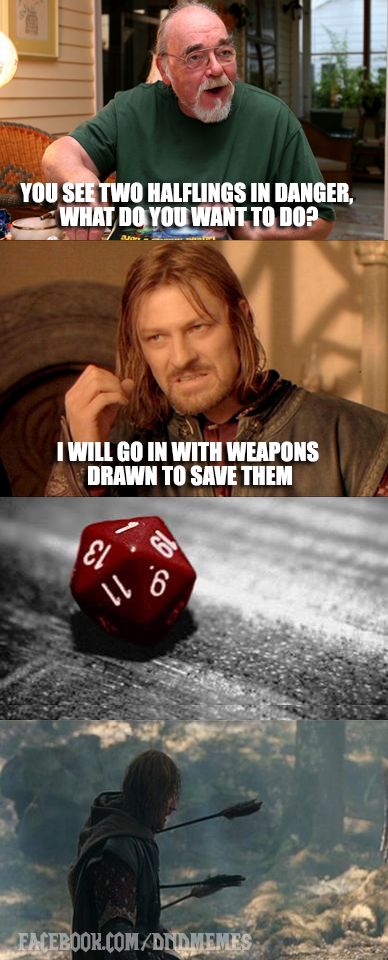

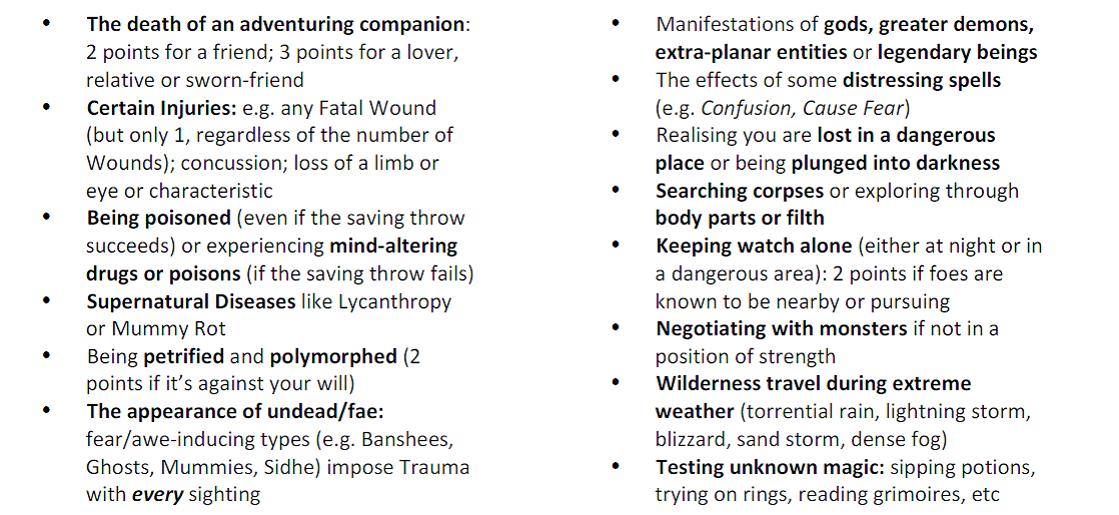

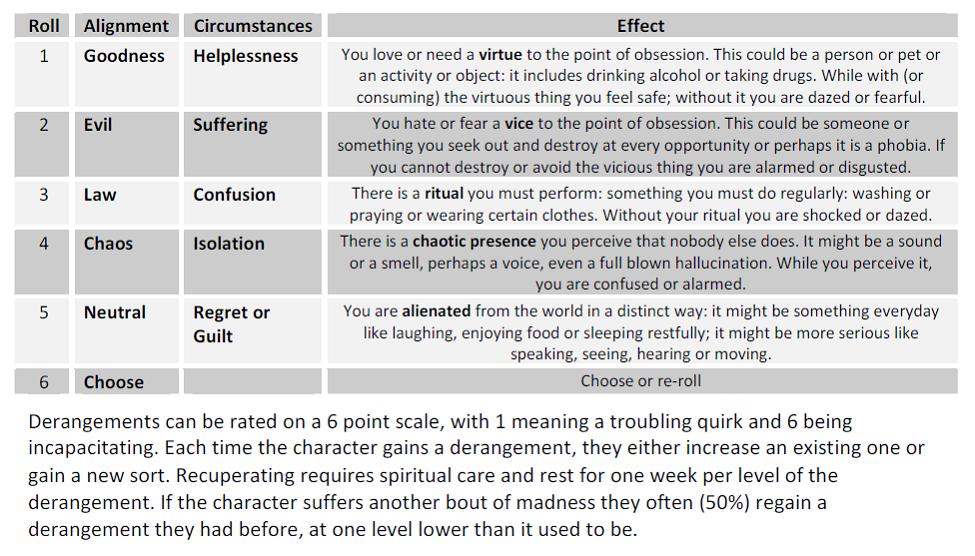

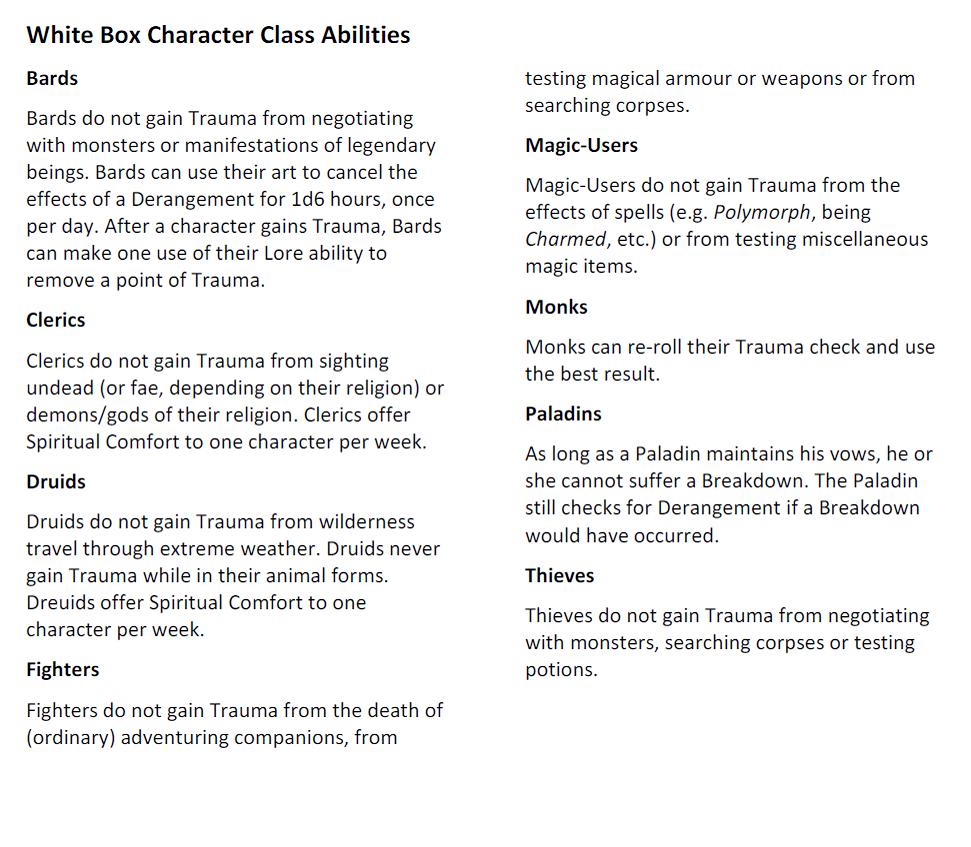

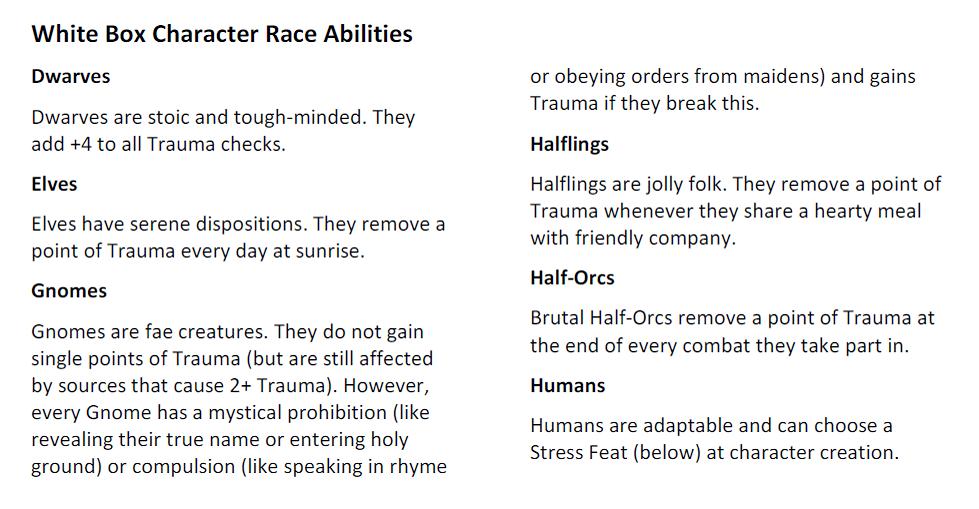

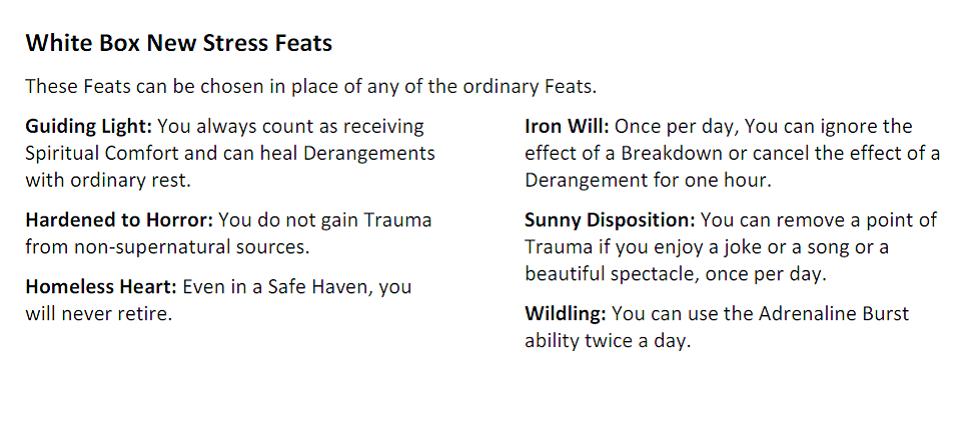

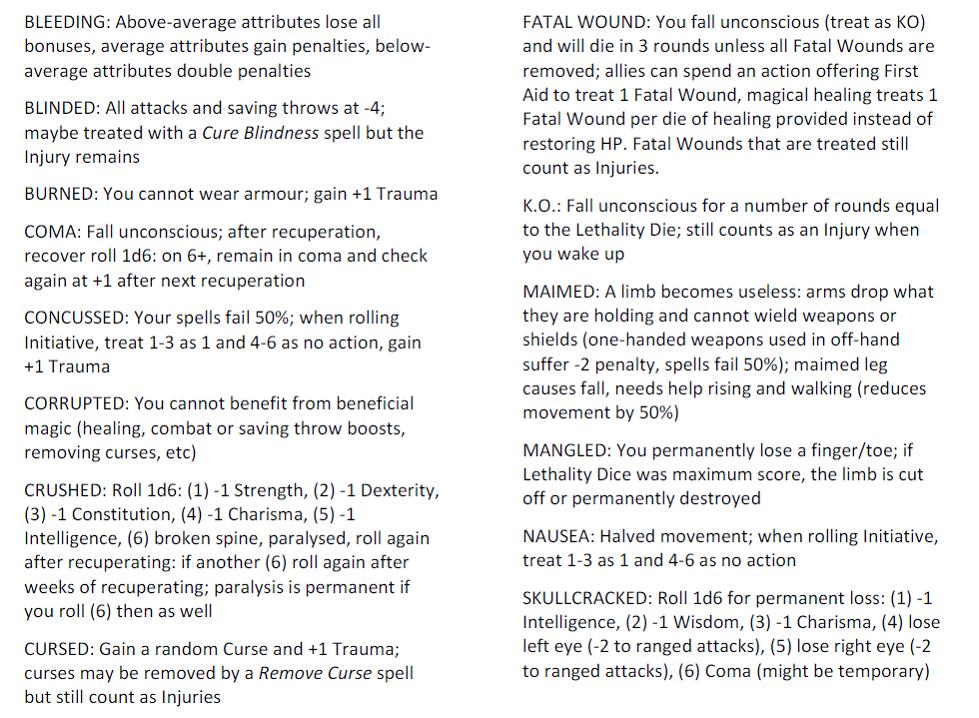

We're playing a campaign using White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game, which makes a virtue out of simplicity. We like to impose a critical hit (maximum damage!) on a 20, so there needs to be a critical failure on a 1. Currently we go with the old drop-your-weapon standby. There's nothing wrong with drop-your-weapon (DYW). It's simple. You can spend a round picking it up again (foregoing your attack) or someone else can pick it up for you (foregoing their action) or you can just draw another weapon and bash on with that. I note with a sinking heart that White Box uses the ghastly one minute melee round (p31) that Gary Gygax introduced for AD&D. Why?!?!? I wrote about this back when I was reviewing Forge: Out of Chaos. In a one minute melee round you have plenty of opportunity to pick up a dropped weapon yourself. Needless to say, my White Box melee rounds are a brisk 10 seconds. The problem with DYW is that it gets a bit boring. Players never get tired of dealing maximum damage but they do get fed up of dropping their weapons, especially the Dark Elf War Smith whose warhammer seems to be made out of banana skins. DYW also gets comedic, which is fine on some occasions but not the vibe you want in more dramatic showdowns. I need to resist the urge to create a complicated Critical Fail table, partly because this is White Box here and partly because whatever I create for PC fumbles will have to apply to monsters too and, as a Referee, I don't want extra book-keeping. Option 1: Fumbles Are Stressful I already use the Trauma & Insanity system, adapted from Goblinpunch. I find it pretty easy to track and it doesn't alter the structure of the game too much, but it helps spotlight scary moments and indicates to players when danger is looming. So far only two characters (both belonging to the same player!) have contracted any permanent derangements, but a few people have had awkward breakdowns. A simple mechanic is: if you roll a natural 1 in combat, gain a Trauma point. Of course, you then have to make a Breakdown Test by rolling over your current Trauma on a d20 (Wisdom modifiers apply) and if you fail that you freak out in the manner of your choosing for 1d6 rounds or else 'suck it up' and waive the penalty at the cost of taking on a derangement. This means combat fumbles don't always produce a bad side-effect, but they contribute to your overall stress and, when they do explode in your face, you could be quite severely discomfitted. The beauty of this is elegance: it relates to a mechanic I already use and my players understand and it's a mechanic which periodically causes PCs to freeze or flee or freak out. Of course, it doesn't apply to monsters - instead, a Natural-1 could cause them to make a Morale Check. There are some monsters (Berserkers, Undead) who simply don't fail Morale Checks, so a Natural-1 is just an ordinary fail for them. Is that a problem? Option 2: Fumbles Are Feints Another view is that a fumble in combat represents, not your clumsiness, but your opponent's craftiness. They feinted or somehow drew you into a reckless attack that exposed yourself. A simple mechanic is: the enemy you are attacking gets a free attack. In other versions of D&D, this could be quite punishing, but remember two things:

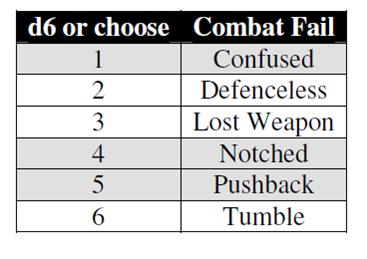

The beauty of this is that it speeds fights up by adding in extra attacks now and again. Given the damage output that PCs have, it probably plays in favour of PCs. It rewards high-HP, high-AC characters who can endure multiple attacks. Most importantly, it's REALLY SIMPLE. You roll a 1 and your opponent hits you: simples. Option 3: A Critical Miss Table It's a classic solution:

This was my first solution, but on reflection it's the least attractive. It's another damn table to roll on. The results won't always make sense in the narrative. It can be unintentionally comedic at the wrong times. But it does introduce uncertainty and drama to combat. One option is to decide which to use on a case-by-case basis, announcing it at the start of any given fight. Being swarmed by Giant Rats or an army of rotting Skeletons is stressful, so Option 1 fits best: your fumbles means the rats are in your hair, the skeletons' bony fingers are at your throat. A duel or matched melee against humanoid opponents fits Option 2 better: you are both trying to break through each other's guard. A party attack on a big enemy fits Option 3 better: if you are all fighting a Dragon or a Giant, it keeps swatting you away and deafening you with its roars.

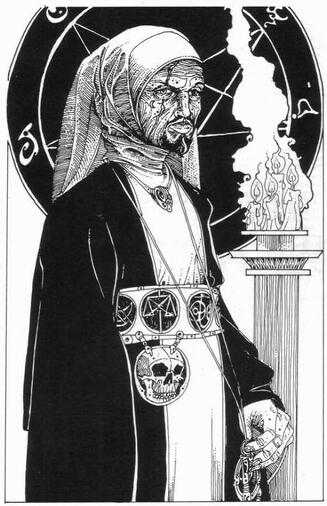

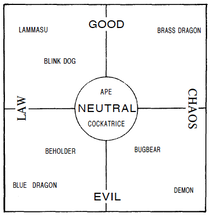

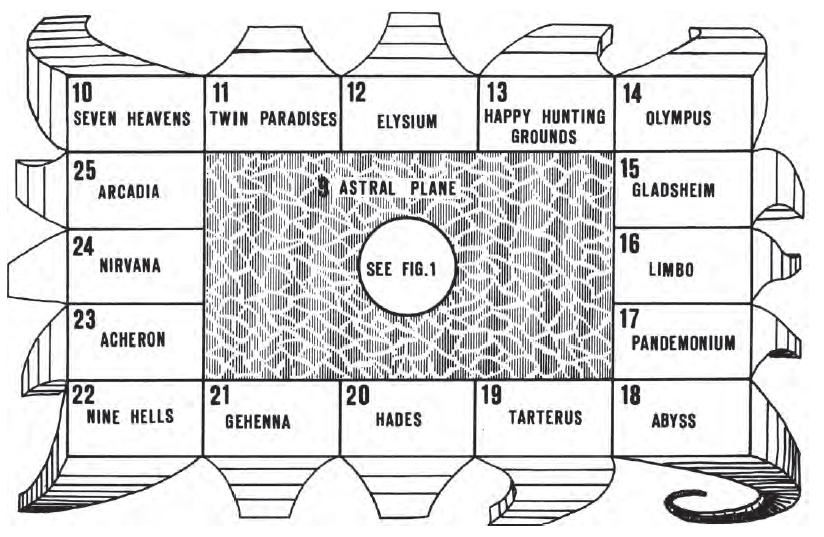

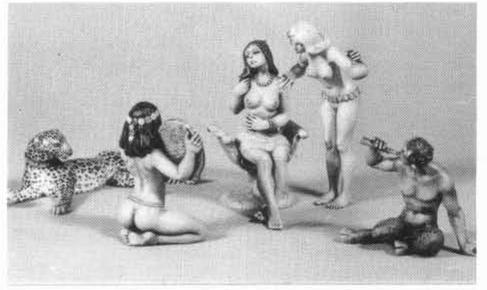

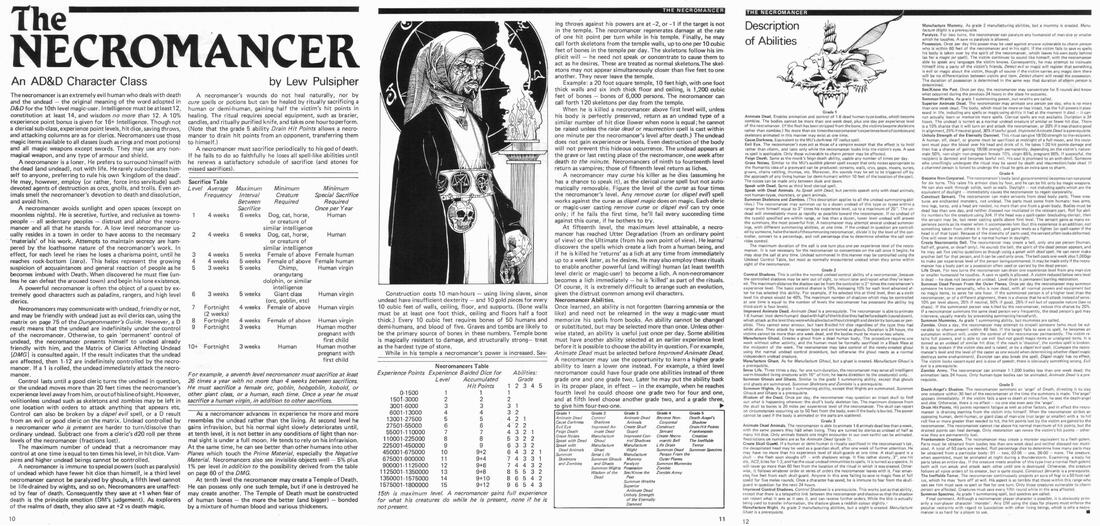

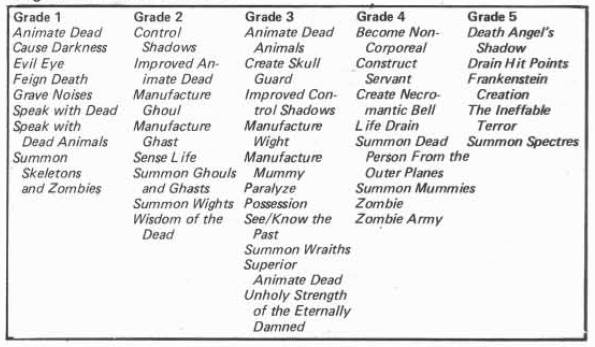

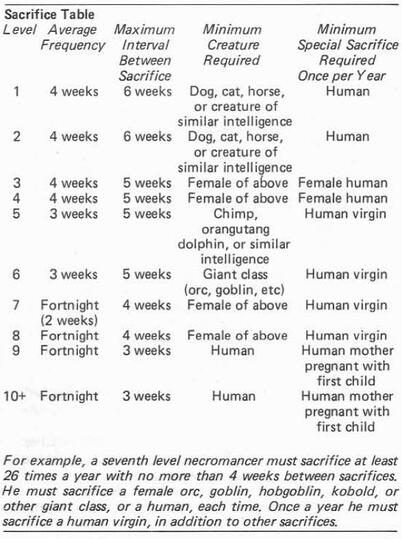

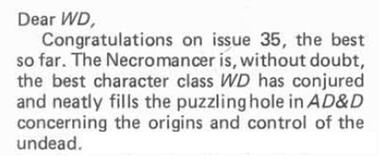

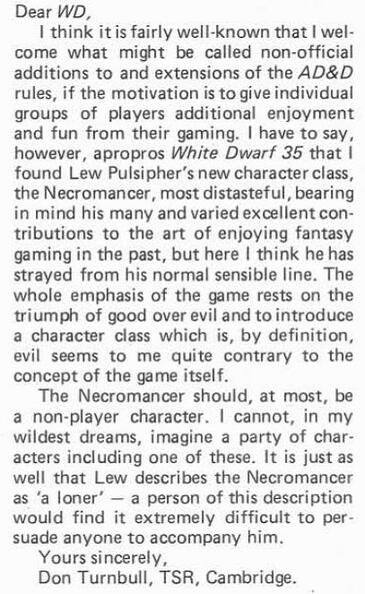

The evil that men do lives after them; It's time to look at the Necromancer class that vexed the correspondents on White Dwarf's letters page in 1982-3. And yes, one of those writers was me! But before I get into the idea of a villainous - if not psychopathic - character class, we need a bit of context. In the early years of D&D, the big debate was "Evil Character" - meaning, evil PCs, of course. Original D&D only featured three alignments (Lawful, Neutral and Chaotic) that lacked clear moral flavour, but Gary Gygax soon added a Good/Evil axis which he inserted into Basic D&D (against Eric Holmes' wishes, seemingly) and made central to AD&D's whole cosmology. Early alignment chart from the Holmes Basic Set (1977) and Gygax's weird map of the Outer Planes, with gods living in different realms based on alignment (Lawful Good in the Seven Heavens, Chaotic Evil in the Abyss) - the sort of thing that only longstanding custom can render un-mysterious It was the arrival of the AD&D Assassin sub-class that made an implicit problem explicit. The OD&D Assassins were neutral (James Bond-style spies or ninjas) but the AD&D Assassin was the first explicitly Evil official character class. Of course, the traditional dungeon adventures of the time didn't offer a wide range of moral options. You could steal from your party members. You could kill your party members. A lot of debate went on about whether PCs should torture and kill monster prisoners. Gygax advised stripping away levels of experience from Good-aligned characters who did such things. Consequently, players adopted Evil-aligned characters to afford themselves more latitude of action. Evil-aligned campaigns flourished, where all the characters were villains and sociopaths. Sickening trails of rape and murder were enacted as (mostly adolescent) players tested the limits of the game and their friends' gag reflexes. You can see traces of this confusion of taste, morality and teenage hormones in the early issues of White Dwarf. There are erotic art and miniature sculpts that later vanished from the magazine. The inside cover of White Dwarf 8 (1978) invited us to enjoy Atlantean miniatures of doubtful dungeon relevance - but such attention to detail...! The fantasy comic strips featured sexual interludes that would make a Warhammer 40K player blush. Lugubrious warrior Kalgar gets some action in David Lloyd's serial, also from WD #8. Then there was the Black Priest in White Dwarf 22. This was an Evil-aligned character class from the pen of Lew Pulsipher. It was introduced with a piece of full-page art depicting a human sacrifice through dismemberment of a nude woman and it's so squalid I can't bring myself to reproduce it here. This was 1980. The '80s brought a mood of moral rearmament. Maybe it was Margaret Thatcher. Maybe it was Mary Whitehouse. Maybe the leading lights of the hobby just grew up and got girlfriends. For whatever reason, the dismembered nudes faded from the pages of White Dwarf, although there was never any shortage of chainmail hotties on the covers. What Armour Class is that, one wonders? The focus of RPGs shifted from playing deranged serial killers to carrying out focused missions in coherent settings. During 1981, Lew's Introduction to D&D series and Roger Musson's Dungeon Architect series promoted a much more respectable view of the things people get up to in RPGs. Penelope Hill's Summoner (#27) and Phil Master's Demonist (#47 and blogs passim) were tasteful affairs compared to the macabre Black Priest. But in 1982, Lew Pulsipher was back, with "an evil new AD&D character class": the Necromancer from White Dwarf 35. Click the cover for a peek at White Dwarf 35 It's not clear whether this is intended to be a valid class for PCs or a purely NPC villain class. The description implies the latter: A necromancer is a loner. He prefers to surround himself with the dead (and undead), not with life. He rarely subordinates himself to anyone, preferring to rule his own 'kingdom of the dead'. With every level the Necromancer attains, he loses a point of Charisma. When it hits zero, he can no longer live in society with other humans. This helps represent the growing suspicion of acquaintances and general reaction of people as he becomes imbued with Death. When discovered he must flee (unless he can defeat the aroused town) and begin his lone existence. This definitely places a Necromancer character outside the purview of players. Or does it? A PC Necromancer with 10-11 Charisma will have reached 'Name Level' before becoming ostracised - the point in their career where most PCs decamp to a fortress of their own to party with their henchmen and stop visiting the local trading store in person. Tenth level Necromancers get to build a 'Temple of Death' out of - wait for it - literally tons of human bones! The Temple of Death must be constructed of human bones - the more the better (and bigger) - bonded by a mixture of human blood and various thickeners. Also from 1982!!! Why embark on such a gruesome career? Let's pretend the Necromancer is an actual PC-option and view it as a character class. There are the usual prerequisites: above average Intelligence, high Constitution and - get this! - a Wisdom of no more than 12! I suppose there's a sort of implied moral judgement here that was lacking in the Black Priest: necromancy is not an equally valid wisdom-path, but rather the thing philosophical cretins get into because they can't grasp real spirituality. Necromancers advance in XP, fight and save as Clerics, including d8 Hit Dice. They can use all armour and weapons. The main power of a Necromancer is undead-wrangling. They can speak with all types of undead and Turn Undead like a Cleric, but they make the undead friendly instead of frightening them away. They can try a second time to 'turn' already-friendly undead and if they succeed these monsters are dominated indefinitely and join the Necromancer's entourage. The Necromancer loses control if the undead wander too far away or get turned by somebody else. Necromancers get a bunch of powers as well that work rather like spells. Necromancers gain these abilities at a similar rate to Magic-User spells, but they cannot seek out new ones (except by going up in levels) and don't need spell books. Once selected, they can use their ability once a day. But you weren't paying attention, were you? You were reading Unholy Strength of the Eternally Damned and thinking, What is that??? You perform it on a minion who drinks the blood of a human sacrifice and has a chance of getting 18/00 Strength (50% usually but higher for females, virgins and pregnant mothers!). Boinnng!!! - you're Lawful Evil now and damned into the bargain. A lot of these powers manufacture, summon or control undead through a telepathic bond. There are some novelties, like manufacturing flying skulls to guard your lair. Later on, you're raising a Zombie Army of 1-1,000 (great if you roll 1,000 but embarrassing if you roll 1), summoning the angel of death and building your own actual 'Frankenstein'! A couple of other abilities stand out. When your Necromancer dies, he can curse his killer - and then return from the dead as an undead version of himself and he turns into a Lich at 15th level! When writing these summaries I normally alternate my masculine and feminine pronouns. With the Necromancer, I don't bother. The text doesn't specify that they are all male, but it seems to be assumed, as we shall see. If turning ugly and creeping off to live in your bone temple doesn't bother you, the Necromancer has one major limitation. Regular living sacrifices. You need to do these to heal, because Necromancers can't regain Hit Points in normal ways (i.e, resting, cure spells) and extra sacrifices are part of the job description. A necromancer must sacrifice periodically to his god of death. If he fails to do so faithfully he loses all spell-like abilities Now I see why there isn't a drawing of a nude, dismembered woman: Lew turned it into a table this time. Sheesh. Picking out one detail of this for special condemnation seems rather to miss the point, but you can't help but shudder at the emphasis on harming women in all of this. Needless to say, White Dwarf readers took up their green biros to write in with praise or detraction. I was one of them, gushing over this horrid confection as only a pompous 16-year-old can: I had a lot more to say about whips and the damage output of crossbows, but let's draw a veil over that. Leave it to Don Turnbull to strike a note of sanity: But Don was shouted down by further letters, including a self-defense from Lew arguing that, since many gamers play characters that are amoral bastards anyway, there can be nothing wrong with providing a character class that channels them into crass and misogynistic murder-fantasies. No, that wasn't quite what he said. Actually, that kinda was what he said... Phew! You can still catch some heat from those old letters-page exchanges. They reflect, of course, the same positions we find on social media today: untrammeled free-expression on one side versus censorious concerns over taste and decency on the other. What's missing from the '80s version is anyone noticing, much less caring about, the issue of the representation of women. The past is another country, my friends. As you can tell, I've gone through an about-turn on this. The moral nastiness of the Necromancer is pretty clear to me now, as much as I was blind to it as a teenager. The point about Lew's creation is that it serves up evil as titillation, a sort of character-class-porn. It doesn't explore evil or necromancy or the metaphysics of death or undeath. It just concocts a Grand Guignol parody of a class and says, 'Here, be as monstrous as you can! Everything is permitted!' Several correspondents compared the Necromancer to the AD&D Assassin, but that misses the point. The Assassin can be played in a variety of ways. Maybe she only takes out contracts on rapists or maybe she uses her skills to strike down the oppressive rulers who enslave her people. Maybe he has an honour code or a devotion to the craft of the perfect kill. But there's nothing to do with the Necromancer because the class does it all for you: assemble an undead horde, sacrifice female virgins, turn into a Lich. There's no other flight path. It's the opposite of player choice and autonomy. Nonetheless, I can't leave matters there. I've been going through the old White Dwarf character classes and revising and re-thinking them. Some, like Phil Masters' Demonist, just needed tweaking into a less ponderous format for perky, up-and-at-'em, White Box. Others, like Brian Asbury's Houri, needed a bit of de-toxifying first. With those classes, I was re-connecting with my teenage self, who had loved them and incorporated them into his D&D campaign. I don't want to reconnect with the adolescent mentality that was so easily enamoured of the Necromancer. If anything, I want to redeem it. There is a role for a 'redeemed' Necromancer. The class does serve a purpose in campaigns above and beyond what Chaotic Clerics get up to. It's intriguing to play an anti-hero, a Faust-figure, someone doomed and invested in their own damnation. There has to be something positive about it though. Aristotle says that men do not become tyrants in order to keep warm: to adapt him, they don't become Necromancers just for a quiet life. Necromancy needs to be a journey, rather than just a dissolution; a mission, not just an act of self-corruption. And those sacrifices have to go...

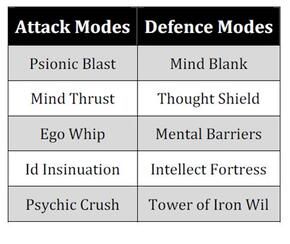

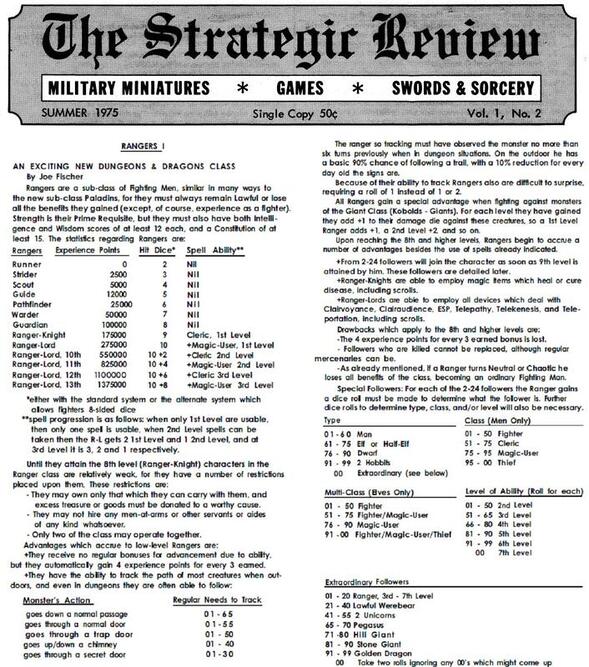

If you work back through 1970s D&D you run into Eldritch Wizardry. And there, sandwiched between the Druids and the Demons, you will find Tim Kask's rules for Psionics. Now if you ever wonder what Macbeth meant when he told his wife that his mind was full of scorpions, you will understand completely when you try to read these rules... At the end of his rather heroic blog, Grey Elf exclaims that these rules are simple and anyone who doesn't understand simply doesn't WANT to understand. Be warned! Psionics are quasi-scientific (rather than magical) mind powers and they came into D&D along this route. Back in 1975, Strategic Review introduced a new monster called the Mind Flayer. The Mind Flayer (great name!) is a nasty squid-headed subterranean villain, nicknamed 'Cthulhu Calamari'. Mind Flayers dish out Psychic Blasts that are brutal even to the toughest PCs and Referees quickly appropriated them into their bestiaries and players went in dread of them. The hunt was on for a PC type that could stand up to such a monster, a counter-measure to the Mind Flayer's "wave of PSI force!" Steve Marsh submitted the Mystic subclass, a mind-over-matter Swarmi. Gary Gygax came up with the Divine, a new class with psychic powers, and tested it with his group. When the third D&D supplement, Eldritch Wizardry, was being developed, Gygax tasked Tim Kask with creating Psionics rules to keep the fans happy. Eldritch Wizardry (1976). It's rather squalid focus on demonology and female breasts put D&D in the firing line in the forthcoming Satanic Panic. But it gave us Druids and Demogorgon! Tim Kask was keen. A simple Psion sub-class would have sufficed, but oh no. Tim decided to use the Psionics rule to 'fix' D&D. Critics complained about the lack of 'spell points' in D&D and the absurdities of the 'Vancian' magic system that caused mages to forget spells as soon as they cast them. Tim introduced a Psionic 'spell points' system to fuel Psionic 'spells' that could be used and reused until the points ran out. Then he created a fiendishly complex Psionic combat system involving points and dice rolls and cross-referencing different styles of attack and defence. The system isn't as unbalanced as critics accused it of being. Fighters lose Strength, Thieves lose Dexterity and Clerics and Magic-Users lose spells as they acquire Psionic powers. Psionics also requires an adjustment to the D&D setting. Referees need to incorporate Tim Kask's monsters into their campaigns and dungeons, critters like the Brain Mole, the Thought Eater and the Intellect Devourer that prey on Psionic PCs and make it dangerous to be a psionicist. This balancing monsters were largely ignored by gamers and when you look at the pictures you'll see why. Oh no, a Brain Mole!!! The Intellect Devourer looks kinda cool, but the Thought Eater?!?!? To be fair to Tim Kask, his Psionics rules were rigorously tested, but badly received. Perhaps a problem was that they don't gel with the established D&D infrastructure. They function like a game-within-a-game, at odds with the normal structures of class, level and roll-to-hit. Or perhaps it is the lack of rationale. Just what are psionics? The indwelling potential of the mind? Extra-planar weirdness from the Cthulhu realms? A recessive gene? An esoteric discipline? Why can't Elves have Psionics? They were famously excluded from these powers, supposedly because D&D designer Steve Marsh was 5'2" and strongly identified with Dwarves and lobbied against his ancestral foes being invited to the Psionics party!

Why can't Druids and Monks have Psionics? I mean Monks??? Gary Gygax opened Psionics up to all classes in AD&D but the Elves were still left out. A final problem is the lottery element to Psionics. You have roughly a 10% chance of developing Psionics. Even those who possess the powers only have a percentage chance each level of gaining new abilities. This means that a few lucky dice rolls make some characters far more competent than others and rob Magic-Users of their distinctive contributions. All of which is a shame for Tim Kask, who meant well, but history is a merciless judge. For the record, Tim looks back on Psionics with these good-natured reflections: I LOVED psionic combat and had great fun devising it with all of its tables and charts. Apparently I was in the tiny minority. I guess mental combat was too esoteric for most D&Ders; not enough of them shared my fondness for the Dr Strange Marvel comics and Mindflayers. God, I loved Mindflayers; they were all over my dungeons. I just loved the idea of turning an annoying PC into a gibbering idiot.. Oh well, live and learn... With the publication of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1978-9), Gary Gygax shunted the Psionics rules into an appendix as an 'optional' system. He removed the link to character classes, so that Psionicists could have any Psionic power based on a lucky roll. He also made them even more rare: the likelihood of having Psionic powers became just 1%, but augmented slightly if you had high attributes. This offers further benefits to already-powerful characters and builds into the lucky few a power progression that other players will never match - because, of course, however unlikely you make Psionic powers, someone will make that roll (or claim they did). The whole system was seen as unfair - and rightly - and widely ignored. Since then, Psionics have ebbed and flowed. They were absent from 2nd ed. AD&D at first, but in the 1990s Sci Fi tinged Dark Sun setting they are ubiquitous. 3rd ed. D&D messed around with them further, proposing various Psionic character classes, which settled into four in 4th ed. D&D. The 'power points' idea to fuel Psionics remained fairly constant, despite being at odds with how everything else in D&D works. 5th ed. D&D tinkered with Steve Marsh's old Mystic class, before abolishing it in favour of the Psionics-for-everyone approach. Which just goes to show that Psionics remains the bane of D&D, the round peg in the square hole, the skull on the banquet table. Early roleplayers discover the Psionics rules. Ha-ha, no: it's Et In Arcadia Ego (1638) by Nicolas Poussin, in which innocent shepherds discover the existence of death. Same thing? Psionics in White Box: first thoughts If we attempt to complete the 'White Box project' of stripping D&D back to its source and then retooling it in the simplest terms, what do we do with Psionics? 'Ignore It!' is one simple and attractive answer. But that feels like a bit of a cop out. The Druid has been reclaimed from Eldritch Wizardry and so have the Demons. Can nothing be done with Tim Kask's legacy? Some Design Principles First, the random chance of Psionic potential has to go. You either choose to be Psionic or you choose not to be. I don't mind NPCs having a 1% (or whatever) chance of being Psionicists, but the point of being a player in an old school Fantasy RPG is that you get to be whatever you want to be. Szymon Piecha introduces an excellent system of Feats in Expanded Lore, so it makes sense for Psionic Potential to be a Feat that grants access to a separate list of Psionic Feats that players can choose from instead of their normal ones when they reach odd-numbered levels. The beauty of this is that, by choosing Psionic Feats, you are foregoing the Class-specific Feats that are so important for shaping your character most of the time. This provides a solid reason not to bother with Psionics. Also, because they get an extra Feat at first level to make up for being racially bland, it maintains (for better or worse) the link between Psionic Potential and Humans. The point-based system has to go. I'm not trying to recreate OD&D here or solve the gaming debates of the 1970s; rather, I'm trying to create a version of D&D as if those debates had never happened, with all the wisdom of hindsight. Out go Psionic Power Points. A different approach is needed. Some things have to stay, not because they are good ideas, but because they are iconic. Tim Kask introduced a set of Psionic Attack and Defense Modes with deeply evocative names: Yes, they're silly and jarring with their pop-Freudian terminologies that don't belong in any conceivable fantasy setting - but any White Box Psionics rules that don't use them are just total non-starters I'm afraid The deeper issue is how to limit the power of Psionics in the game and this has to be linked to the explanation for what Psionics are. One view of Psionics is that they are a perfectly natural potentiality in sentient minds that comes to the fore in some people, perhaps through rigorous mental training or some sort of genetic blessing. George Lucas started off treating the Force as the former, then switched to viewing it as the latter. The Force: started off as a mystical energy, turned into a blood disorder This tends to present Psionics as a fulfilment of human (or demi-human) potential. There might be a natural limitation to Psionics, which is exhaustion. Use the power too much and it short-circuits and you need long rests before it returns. A different view is that Psionics are an aberration, something deeply unnatural. Perhaps they are gifts from eldritch entities, insights into things no mortal was meant to know, the side-effects of perceptions into a cosmic reality that ordinary thought cannot conceptualise. In this case, Psionics can carry their own internal penalties: the risk of madness. Or aberrant Psionics can carry a more external risk: we need Tim Kask's psionic predators. Unleash the brain moles! Or, y'know, a mix of these. If you want Psionics to be a Lovecraftian phenomenon, then using them too freely will both drive you mad and attract the attention of extra-planar gribblies with three-lobed burning eyes. If I'm going to offer up a set of White Box Psionics rules, it needs to be setting-agnostic. So I'll need a mechanic that can be interpreted in all of these ways. The final consideration is that Psionics should be unobtrusive. If one PC develops Psionic powers, it should not skew the game around their powers or the particular challenges they face. Yet despite this, Psionics need to have a distinctive flavour of its own, otherwise it's no different from having access to a few magic spells. Getting the balance right isn't easy. A possible mechanic I'm toying with a system like this: after using a Psionic power, the psionicist makes a saving throw, having to roll higher than the number of times they've used their powers so far (say, on a d12). If you fail, you wipe away all your accumulated usage and start afresh but a Bad Thing happens - maybe you become exhausted or gain a derangement or attract a brain mole! One advantage of this is fairly minimal book-keeping. You're just keeping track of the number of times you've used your powers so far. Another is that it fits in pretty well with the house rules for Trauma & Derangement, which already function like this (you accumulate Trauma and make checks until you fail to roll over your current total, in which case you go crazy).