|

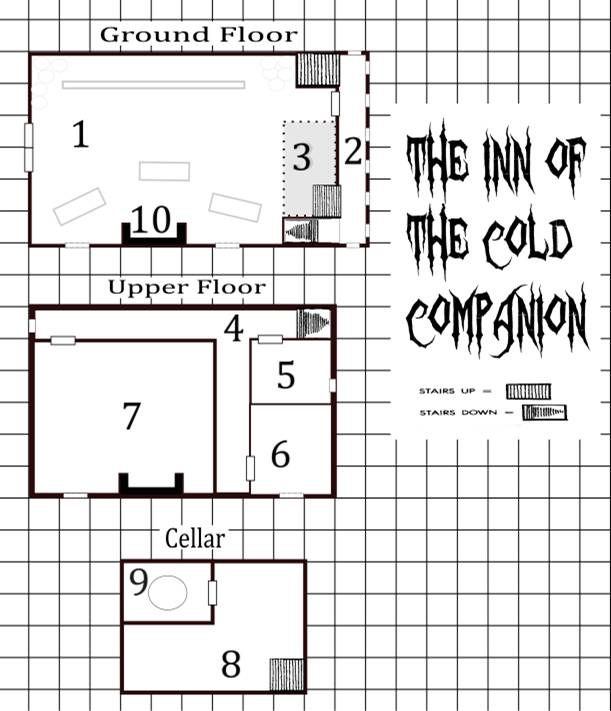

The Inn of the Cold Companion is a 30-minute Dungeon Challenge, as set out by Tristan Tanner in his Bogeyman Blog. I hope it will inspire other people to create some of their own and send them to me - so I can hand out free copies of Forge Out Of Chaos as prizes in the January 2020 competition I used Tristan's optional tables to create an extra discipline for this 10-room dungeon: empty rooms that point to a combat, reveal history and offer something useful to PCs; the special room provides a boon for a sacrifice; the NPC is a rival; the combat encounters are a horde of weaklings, a pair of toughs and a tough boss; the traps are inconveniencing and incapacitating. Background (Referee only) The Inn is a place in the realm of death where the souls of the dead gather on their way to the Netherworld. It was once a real Inn that entered the realm of death when the Innkeeper Rosenkrantz, deranged by grief after the death of his wife Ophelia, burned it down around him. Dead souls will not rest here long, before the Cold Companion (an avatar of Death) comes to collect them. Dead souls do not realise they are dead: they believe they are resting on a long journey but have only hazy ideas about their destination. They also do not know their names and the only treasure they carry are two silver obols each (the coins to pay for their passage). In this scenario, the players are members of a party of adventurers who have died in a disastrous dungeon encounter, but in the living world their cleric-cum-medic is struggling to revive them. Hook You are bone-weary from travelling and there are still leagues ahead of you, but the last light of a wintry day shows a roadside inn ahead, with a lantern glowing faintly above the door. The creaking sign bears the name ‘The Cold Companion’ and the image of a feral child with sparkling eyes. Your rations are spent and your waterskins empty, but there are coins jangling in your purses. You enter, look for rest and perhaps fellowship from other travellers on this dismal highway. Special Rules In this scenario, characters do not know their Names (q.v.) when asked and cannot remember each other’s names or even think of any names at all. Players can describe their appearance and origin (but no names, of countries or towns) and know each other’s achievements (famous deeds, reputation, shared exploits, but no names of places or enemies) and may refer to each other by this (‘Dwarf’ or ‘Goblin-killer’ or ‘Elf-lover’). The only exception is priests who will remember the name of their god. The players have no rations (all spoilt), water or wine (spilt or sour). Forge characters have no armour repair kits, binding kits or healing roots. If players bought these accessories, they are mysteriously rotted or simply vanished. Regardless of initial moneys or treasure from previous adventures, each character has just 2 silver pieces (obols) on their person. Fire cannot be lit in the Inn, except for Rosenkrantz’s candle. Spells which create magical fire will not cause other objects to burn (exception: room 6). The rooms are lit by an eerie radiance from the windows; shuttered rooms are pitch black until the shutters are opened. The Cellar (8 and 9) is pitch black unless Rosenkrantz is there with his candle or magical illumination is used. The candle in 7 will help the PCs a lot. Allow players to discover these absences and mysteries through play (i.e, when asked their name or when they try to pay for something). 1. The Common Room This is the public bar with three long trestle tables and benches set around a big stone Fireplace (10) which is piled with kindling but unlit and cold. There is a bar, with shelves behind holding tankards and bottles, and big tuns at either side with spigots for dispensing beer or cider - but everything is utterly tasteless. The room is high-ceilinged (20’) and overlooked by a minstrel’s gallery (3). The windows to either side of the fireplace present a Spectral Vista as will the door if PCs try to leave. If the PCs make noise or call for service, Rosenkrantz will appear, pretending to be the innkeeper. If the players spend too long here or return to this room, the Undead Patrons will arrive. 2. Corridor of Windows This dark corridor is lit by the windows, which present the same Spectral Vista. When the PCs cross the corridor, skeletal hands break through the windows and attack. Each PC is grabbed by 1d4 hands, which attack as 1HD monsters (Forge: as AV 2) and deal 1 damage. PCs who are grabbed may be pulled through the window on the following turn; they must Save vs Death (D&D, at +4), with a -2 penalty for each hands holding them. An ally may try to save a character being pulled through the window: this allows a second Saving Throw with an additional +2. The arms may be turned as Skeletons or attacked (treat armour as leather and a single hit destroys one). If the PCs returns to this corridor or pass through in the company of Rosenkrantz (when he shows them to their rooms), the windows will be once again intact but the arms will not appear. There are three staircases: up to the upper floor (4), up to the Minstrels’ Gallery (3) and down to the Cellar (8). 3. The Minstrels' Gallery This balcony commands a view of the Common Room (1) 10' below. While PCs are up here, the Undead Patrons will arrive. There are musical instruments here (harp, lute, citern, recorder, violin) and any PC will find themselves able to play mournful tunes on them. A character who can play or sing will find themselves able to recall a sad ballad of the death of a beautiful woman named OPHELIA; the singer can bestow the name on one character (including him or herself). 4. Shadowy Hallway The only light in this corridor comes from the window at the far end, which presents a Spectral Vista. A dark shadow lies across the floor. Anyone stepping on it must Save vs Death (Forge: at -2) or fall into it, disappearing. Anyone putting their hand into it feels numbing cold and cannot use their arm for 1d12 minutes. Objects placed in the shadow are withdrawn covered in frost. Any PC falling into the shadow arrives at the front door of the Inn all over again, in the company of anyone dragged through the windows (2), with no recall of being here previously and any Names (q.v.) that have been learned are forgotten. The shadowy hole temporarily disappears in light: from a candle (in 7 or carried by Rosenkrantz) or magical illumination) but reappears in darkness. Players might use this to their advantage against the Cold Companion. 5. The Guest Room This room is unlocked but, if Rosenkrantz shows the PCs to a room, he will bring them here and lock them inside. There are six bunk beds and a chest for goods and several weatherstained cloaks on hooks. Scratched on the inside of the door is a message: THE COLD COMPANION IS COMING. Under one of the beds is an old pair of boots with a name written inside: YORICK; anyone putting on the boots acquires the name. Characters who sleep in this room dream of dying in battle against monsters in an underground dungeon; one character hears their name being called over and over from the Well (9) downstairs. The window is shuttered but, if opened, reveals a Spectral Vista. 6. The Innkeeper's Room This room is locked and piled with junk: the possessions of former travellers can be determined on a random item table. The room smells of soot and ash. The Innkeeper’s Ledger is kept here and bears the Innkeeper’s name ROSENKRANTZ on the inside cover. Under the bed is a sack containing thousands of silver pieces: the payments of countless previous guests. This is the only room in the Inn where fire can be started and objects can burn: if a fire is started here, creatures inside take 1d6 damage on the first round, then 2d6, then 3d6 and so on. If the PCs do not summon him to the Common Room (1) or discover him in the Cellar (8), Rosenkrantz can be found here, counting his coins. 7. The Master Bedroom The door is locked and Rosenkrantz does not have a key to it; listening at the door, PCs will hear a man sobbing but if they enter there is no one within. If someone bearing the name of 'Ophelia' is present, the door will open for them. This grandly appointed room has shuttered windows that display a Spectral Vista if opened. The bed is laid for a funeral, with vases of flowers: rosemary, pansies, daisies, violets and rue. An ever-burning candle (similar to Rosenkrantz's) is set beside the bed and can be taken by the PCs; it sheds light in a 10' radius. Paintings on the wall show the Inn in a busy city street; a portrait of the Innkeeper and his beautiful wife; a deathbed, clearly in this very room, with the Innkeeper grieving; a terrible fire burns the inn down, the Innkeeper clutching a ledger can be seen in the window of the Innkeeper’s Room (6). The final picture shows a creature advancing through the doorway to the Inn: a pale child with sharp teeth and shining eyes. The Innkeeper in the paintings is not the one the players might know as Rosenkrantz. 8. Cellar If the PCs did not summon him to the Common Room (1) or find him in the Bedroom (6), Rosenkrantz is down here, endlessly dragging heavy barrels around while he repeats his name over and over to himself. He will offer to show PCs to the Common Room (1) then bring the Innkeeper's Ledger and then escort them to the Guest Room (5). He will go to great lengths to stop them discovering the Well (9). 9. The Well of Souls The well is a deep shaft in the floor, near;y 10' across. A voice calls out of it, calling to one of the characters by name (determine which player randomly: that PC now knows their name). Any character trying to descend into the well falls into darkness and experiences the Medical Intervention. This character then wakes up in the Master Bedroom (7). 10. The Cold Fireplace After the Medical Intervention or the final Spectral Vista occurs or when Rosenkrantz lights it, the fireplace erupts with blue flames that give off no heat. After 1d6 rounds, the Cold Companion enters the Inn, seeking out any characters without names. If the PCs defeat the Cold Companion, they awaken in the living world. 'Rosenkrantz' This is another dead soul, a thief, who has been at the Inn for untold ages. When he arrived here, he stole the Innkeeper’s name (Rosenkrantz) so that the Cold Companion took the old Innkeeper instead of him. Rosenkrantz plays the role of an oily and obsequious Innkeeper, but delights in the players’ confusion and enjoys taunting them by asking them for their names on any possible occasion and teasing them with the imminent arrival of the Cold Companion. He carries a smelly tallow candle at all times that never goes out; he will not share it with guests or let anyone else use it to light the Fireplace. He also carries keys to lock rooms 5 and 6. He has the following rumours to impart:

Rosenkrantz cannot be killed except by the Cold Companion or by a fire in room 6. However, if the players acquire the Ledger and steal his name, the former-Rosenkrantz will use his candle to light the Fireplace (10) and summon the Cold Companion, hoping to trick the players into giving him back his name in return for protection (a lie: he has none to offer). The Ledger If the PCs summon Rosenkrantz to the Common Room (1) or meet him in the Cellar (8), Rosenkrantz will offer to provide them with a room at a cost of 2 silver pennies. He will ask them to sign the Ledger (and might have to head off to room 6 to fetch it if encountered in the Cellar). The ledger is full of pages where previous guests signed in (as the nameless players must do) with X. The inside cover has an inscription: ROSENKRANTZ, HIS BOOK, AND HIS LOVELY WIFE. Any character holding the book and reading this aloud acquires the name of Rosenkrantz and the previous Rosenkrantz becomes nameless. The Undead Patrons Two leather-armoured warriors arrive at the Inn, demanding service. If the PCs do not interact with them, Rosenkrantz will appear with his Ledger and book them in: they too have a pair of silver obols each. The nameless men are cheerful and keen to talk and play dice with other guests. They will explain how they were exterminating the undead in a haunted cemetery just last night; their companion was killed by an undead creature and they buried him; they had been concerned that he might rise as an undead monster himself and come after them, but clearly that has not happened, which is why they are celebrating. During the interaction, the Patrons start to change, because of course they were killed in the night by their former-friend and are now turning into undead themselves.

Medical Intervention The player in the Well (9) experiences waking up in a dungeon corridor, surrounded by corpses. A female cleric (Forge: Berethenu Knight) is trying to staunch their wounds and pleading with them to ‘stay with me’. The player can utter three words before the vision ends and they return to the Inn. This scene is really happening in the living world. The corpses are the other PCs, killed in an attack by wandering monsters. The cleric is GERTRUDE and if asked she can offer her own name, the name of the dying PC and any other names that a three word question could elicit. After the Intervention, the fire lights in the Chimney (10) and the Cold Companion will soon appear. The PC awakes in the Master Bedroom (7). Names It is vital the players acquire names. They might steal ROSENKRANTZ’s name from the Ledger, acquire OPHELIA from performing music (3) or learn their own names or that of GERTRUDE from the Medical Intervention; YORICK can be discovered in the Guest Room (5). Clerics (Forge: Grom Warriors/Berethenu Knights) will know the name of their god and can take this name upon themselves, once only for 1d6 rounds. Spectral Vistas Looking out of the Inn (from rooms 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7) reveals a supernatural landscape. Roll 1d6 for each different occasion, adding +1 for each previous Vista that has been viewed.

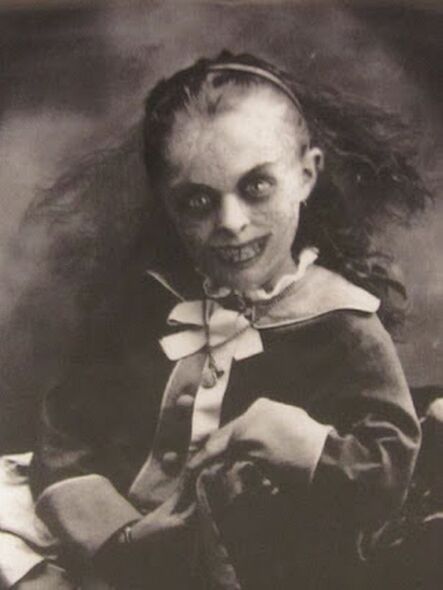

The Cold Companion This avatar of Death appears as a pale and feral-looking child, with razor sharp teeth, glittering eyes and sharp, filthy nails. It moves to attack nameless characters and ignores those with Names. Characters killed by the Cold Companion turn into balls of floating blue fire, which the Cold Companion gobbles up: this also takes 1 round, buying respite for other PCs. If a named character deals damage to the Cold Companion, it will be able to attack once in retaliation. The Cold Companion appears when a now-nameless ‘Rosenkrantz’ summons it, in which case it eats him first (despite a scene where he pleads or promises: Death is not to be cheated by thieves), giving the PCs a melee round of respite. It also appears after the Medical Intervention or the final Spectral Vista. In D&D, treat the Cold Companion as a Wight but ignore it’s immunity to normal weapons. Level-1 PCs struck by the Cold Companion are instantly killed by the level drain unless they have a name, in which case they forget their name instead. In Forge, the Cold Companion is a Death Hag and named characters who fail to Save vs Death will forget their name rather than be destroyed. If the Cold Companion falls into the shadow pit (4) or the Well (9), it is defeated. If it can be lured to the Innkeeper’s Room (6), it can be trapped in a fire which will then spread and destroy the entire Inn. When the Cold Companion is destroyed, any remaining characters leave the Underworld and recover in the dungeon, at the site of the Medical Intervention: they have returned from the dead. Commentary "And they were really dead the whole time!" It's a cliche of TV and film, but it's still a fresh conceit in a roleplaying game. This scenario assumes the players have experienced a TPK (Total Party Kill). If the players create new characters, then the TPK is an aspect of their backstory that they have forgotten. Have fun dropping this scenario in if the players really do experience a TPK! This was my attempt to create a Twilight Zone style 30 minute dungeon. The dungeon itself took 30 minutes, but writing up the rules for Rosenkrantz, the Undead Patrons, the Spectral Vistas, etc., took longer. The scenario assumes half a dozen PCs, who could all be 1st level. If the number of PCs is half that, they should be 2nd level and the Referee should remove Yorick's Boots from room 5 and trigger the arrival of the Cold Companion as soon as there is only one un-named PC left. I hope there's some pleasure for the PCs in figuring out the Inn's mysteries: even if they quickly realise they are dead, there's still the puzzle of Rosenkrantz and the history of how they original Innkeeper destroyed himself and the Inn. The players might decide to leave the Inn. The Spectral Vistas are designed to discourage that but if the PCs insist, introduce horrid Sandworms (as in Beetlejuice) to gobble them up, with PCs awakening back at the Inn (in their Guest Room, probably) and with names forgotten, to teach them a lesson. Rosenkrantz is intended to be a nuanced NPC. I think he's been at the Inn for centuries and is quite mad. He's a mixture of humble-grovelling towards guests and smug-sarcasm, delighting in being mysterious and showing that he knows more about what's going on than he will reveal. If the players want to attack him, allow him to run into a shadow, like the one in 4 but instead of being ejected from the Inn he escapes to the Innkeeper's Room (6). This is a unique power he has learned from spending so long at the Inn. The Cold Companion is meant to be an eerie, fey sort of psychopomp. I imagine it to be Ophelia's unborn child, grown into a sharp-toothed demon-thing. It giggles in a high-pitched voice, skitters about the place on slap-slap-slap bare feet and scratches at doors with its horrid nails. It cannot be reasoned with, though it might back off (briefly) from fire or the flowers from the Master Bedroom (7). Have fun with it.

If you want a less-violent, more spiritual sort of climax, think about how the players could relate to the Cold Companion. If the Companion truly is Ophelia's unborn child who died with her mother and then was incinerated in the fire, it might be possible to reach out to her, especially if a PC has taken on the name of OPHELIA or ROSENKRANTZ and recognises the child as their own. The Companion's grieving reaction to the flowers in 7 and pained response to Ophelia's theme played on the instruments in 3 might provide clues. Alternatively, players might improvise names for themselves based on their behaviour within the Inn: 'Shadow-tripper' or 'Well-diver' are riddle-names of the sort Bilbo offered to Smaug in The Hobbit and Referees should reward this sort of creativity. It's possible that all the remaining PCs end up with names, especially if someone used their three-word question in the Medical Intervention wisely. In this case, they are immune to attacks from the Companion and Referees should not force a battle. Players might overcome the Companion by showing it kindness or simply a lack of fear. Again, Referees should reward thematic roleplaying. Conquering death doesn't have to involve killing something, after all.

2 Comments

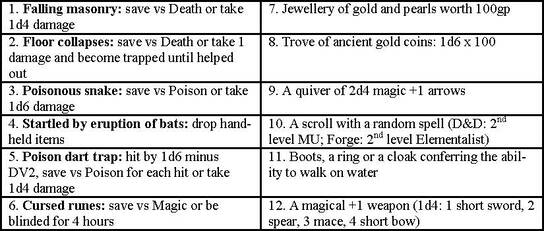

Bury My Tusks at Broken Jaw is a 30-minute Dungeon Challenge, as set out by Tristan Tanner in his Bogeyman Blog. I hope it will inspire other people to create some of their own and send them to me - so I can hand out free copies of Forge Out Of Chaos as prizes in the January 2020 competition I used Tristan's optional tables to create an extra discipline for this 10-room dungeon: empty rooms that point to a combat, reveal history and offer something useful to PCs; the special room provides a boon for a sacrifice; the NPC is a rival; the combat encounters are a horde of weaklings, a pair of toughs and a tough boss; the traps are inconveniencing and incapacitating. In this scenario, players can use Ryan Marsh's goblin PC class (and allied Hobgoblins and Bugbears). Background The goblin kingdom was overthrown by the invading Elves of the Pale Empire (‘Foam’, as the goblins call them, for their pale skin). After the death of the last Goblin rajjor (king) San Rankill, Goblins were sent to live in Munaan (reservations). One such as Broken Jaw, deep in the swampy Watching Glades. Now the Elves have arrived to evict the goblin chief (Keth) and his sworn companions, herding the tribe into a stockade where they will be deported to the slave markets. Hook The Elves came in the night on their silent ship to Broken Jaw. Your cousin Botang brought you warning and you escaped the Munan (reservation) on canoes while he sacrificed himself fighting off the Bleach (Elves) and their Mudskin (Human) henchmen. Many of your companions died in the Swamp of Ghosts but dawn finds you camped in the Old Boneyard, warming yourself round a feeble fire, while you plot your revenge. Player Map One of the PCs is the Keth (chieftain) of the goblin reservation of Broken Jaw. The scenario involves his or her attempt to recapture the island home and expel the imperial Elves and their Human mercenaries. Create characters for D&D based on the Goblin class by Ryan Marsh. Optionally, allow one PC to be a grizzled Hobgoblin sergeant who trained the young Keth in arms. Another PC could be a Bugbear, an old family retainer. If there are 6 PCs, they can all be 1st level; for each PC fewer than 6, promote one character to 2nd level, starting with the Hobgoblin sergeant, then the Keth, then the Bugbear for a group of three 2nd level characters. In Forge, the Keth and his or her comrades should be Higmoni, the sergeant a Berserker and the retainer a Ghantu. If there are fewer than 6, consider promoting their level of Melee or Magic skill as above. Referee's Map 1. A Cold Night in the Old Boneyard The PCs start here, at sunrise. They are equipped with only leather armour and their krist daggers (damage 1d4+1). The swamps below are covered in mists. Each PC rolls 1d6 for rumours about their surroundings (add +1 if Wisdom 13+ or if History skill is used):

If the PCs search the boneyard, they will find caches of ancient weapons; roll 1d6 for each PC (add +1 if Intelligence 13+ or if Search roll successful)

2. Bomoch's Hut Bomoch the Greenseer lives in a squalid hut of leather tents and woven reeds. All around the hut dead weasels hang from lines and Bomoch keeps many weasels in cages (to keep away Cockatrices, of course). He is a wild-eyed, cackling maniac but he has been expecting the PCs. Bomoch greets the Keth as a great lord and volunteers a safe route following an ancient causeway north through the Swamp of Ghosts. He warns PCs not to stray from the causeway into the mists: Penanggouls will imitate the voices of loved ones and Cockatrices turn you to salt with their bite. Bomoch tells the Keth that the Jade Queen is waiting for him or her inside the Emerald Labyrinth. He will offer no more clues except to direct the PCs to 3 and instruct them to eat the fungus growing on the trees near the old totem pole. Bomoch offers other advice to the other PCs, roll 1d6 for each (+1 if Charisma 13+ or possess the Charisma trait)

3. Into the Emerald Labyrinth The PCs will be sent here by Bomoch (2). The trail ends with a sinister klireng totem pole before the wall of dense forest. If the PCs consume the fungus growing on the trunks of nearby trees, they will experience a vision in which a trail opens up into the forest. Following it takes them to the Bower (4) along a path that is almost lightless because of the canopy of branches overhead. The Referee should add haunting and scary details to the journey or roll/choose for each character:

Any deaths or Hit Points lost during the vision are recovered at the end and the PCs awake outside the forest, with the sun now in late afternoon and the day nearly over. 4. In the Bower of the Jade Queen The vision quest concludes in a clearing in the heart of the forest, watched over by a final brooding klireng pole.

5. The Causeway through the Swamp of Ghosts If the PCs took Bomoch’s advice, they can follow the causeway. Along the route are salt pillars (petrified victims of the Cockatrices). The Referee should alarm the players with the reptilian slithers of Cockatrices in the mist. If the PCs visited the Emerald Labyrinth it will be dusk and they may sight Penanggouls, floating heads that call to them with the voices of loved ones. Half way through the swamp, there is a high mound marked by a totem pole. A scouting party of 10 Humans are camped here; they are servants of the Elves. Human Scouts: (D&D) HD 1, HP 3, AC leather & shield, spear for 1d6 or javelin for 1d6; (Forge) HP 15, DV1 3, DV2 2, 15AP, 5SP, AV 1, spear for 2d4 or javelin for 1d6, ST 12+, SPD 3 If the PCs eavesdrop on the Humans they might learn things (roll 1d6 for each):

If the PCs did not visit Bomoch, they will not find the causeway. They will wander for hours in the swamp and find themselves stalked by Cockatrices. Bomoch will arrive to save them, carrying a weasel in a cage to frighten the Cockatrices away. He will guide them to the causeway and accompany them to the Slave Stockade (6). In this case, Bomoch will offer his puzzling omens but will not tell PCs about the Jade Queen. 6. Attacking the Stockade The Goblins used this area as a timber yard for valuable hardwoods felled in the Watching Glades. Now the Elves have imprisoned the Goblin tribe here and set their Human soldiers to watch over them. There are 20 Humans: 4 guarding the bridge and 4 in the watchtower and another 12 standing guard over the prisoners. See 5 for their characteristics. The Goblin prisoners are all tied up.

The players need a plan to pick off the guards quickly, under cover of night or fog, perhaps freeing the prisoners to aid them. Once this is done, they can free their loved ones. Each PC has a significant NPC to free:

However, many prisoners are missing including at least one of the special NPCs. They were taken last night by a creature of darkness and dragged away into the Watching Glades (7). The stockade contains a supply of limes (to feed the prisoners). For D&D, there will be a Potion of Healing. For Forge, there are leather and shield repair kits and tools as well as 2d4 Binding Kits. 7. Through the Watching Glades If the PCs choose to go in pursuit of the kidnapped prisoners, Bomoch will not accompany them (if he has come this far). It will be night time and the jungle trail is treacherous. At the other side of the jungle, stepping stones cross the river and the ruins of the old kings are visible in the moonlight. Roll 1d6 for each PC to find out what happens on the journey (for irony, don’t roll and choose an event that matches the vision encounters described at 3):

8. To the Ruins of the Old Kings The statuary and wall carvings here surprise the PCs: the old kings, the Rajjors, who ruled here were not Elves, but Goblins. PCs with Intelligence 13+ (Forge: History skill) will conclude this was the palace of San Rankill, the last Rajjor. A statue depicts him riding a water dragon (Naga). The throne room is now the lair of a Jembalang. This scaly, bat-winged demon has been awoken by the arrival of the Elves and sends out its ghost-body to capture victims to eat. Jembalang: (D&D) HD 6, HP 30, AC as leather & shield, 2 claws for 1d4 each and bite for 1d6, flies, hypnotic song; (Forge) HP 45, AR 3, AV 5, 2 claws for 1d4 and bite for 1d6, ST 11+, SPD 4/8 flying The Jembalang uses its projection to swoop down for a surprise attack but this will flee as soon as it is injured and can be tracked back to the throne room, where its entranced victims are kept. The true Jembalang (which takes any damage its projection took) will use its hypnotic song: all PCs must Save vs Magic (Forge: vs Mind) or slip into a trance. Entranced PCs can be shaken awake by others (they get extra saving throws for each round of this and save at +4 if they taste or smell limes) but once it has sung its song the Jembalang will attack. When the Jembalang dies, entranced victims wake up. A mighty roar from the south (9) indicates something else has woken up. 9. The Old Stones at Kuala These old stones are the ruins of a wharf and jetty. The Goblins just know them as ‘old stones’ but respect them because many have Naga-symbols on them. Once the Jembalang (8) dies, the entranced Lake Dragon wakes and comes to the surface here. This is Radiant Pang, a giant, intelligent crocodile that faithfully served San Rankill and will serve the new Keth too. PCs can ride on Pang’s back across the lake and Pang will attack and sink the Elven ship, forcing the Elves to swim for the dubious safety of the Swamp of Ghosts. 10. Showdown on Broken Jaw Island The PCs might arrive here at dusk (if they came directly to the Stockade and ignored the mystery of the kidnapped prisoners), in which case the freed Goblins will assault the Elven ship while the PCs come ashore. If they fought the Jembalang, the PCs will arrive at midnight on the back of the Lake Dragon. If they went to the Emerald Labyrinth first, they will arrive at midnight (if they ignore the Jembalang) or before dawn (if the destroyed it). To recapture their home, they need to confront the Elven Captain Zeng and his ally, the traitor Botang. Creeping through the deserted village, the Goblin PCs overhear the two villains argue in the Keth's Hut: Botang: You make me Keth and leave me to rule over an empty rock? Zeng: Perhaps not even that... Botang: You betrayed me! Zeng: [Angry] You talk of betrayal? To me? Watch what your crooked lips say, Ular (= snake or goblin) Botang: [Pleading] They are my people! Zeng: No, Ular, they are the Pale Emperor's slaves. Botang invited the Elves to install him as the new Keth in return for the valuable hardwoods the village harvests, but the Elves have left him as chieftain of an empty island when they took his tribe away to be slaves. Nevertheless, when the PCs arrive, Botang will fight beside his new masters unless the PCs can appeal to his shame. Zeng, Elven Captain: (D&D) 3rd level, HP 16, AC chain and shield, broad sword for 1d8, Magic Missile, Ventriloquism, Mirror Image; (Forge, Elf) HP 16, DV1 5, DV2 4, AP 40 SP 10, AV 3, broad sword for 1d8+1, ST 9+, SPD 4 Botang, would-be Keth: (D&D) 3rd level, HP 14, AC leather and shield, krist for 1d4+2, javelins for 1d6; (Forge, Higmoni) HP 15, DV1 3, DV2 2, AP 20 SP 5, AV 3, krist for 1d4+2, javelins for 1d6, ST 8+, SPD 3, 2nd level Beast Mage (Jump, Spike, Fangs, Rending, Sonic Wail) If the PCs overcome Zeng, the ship will be captured (by the freed Goblins) or destroyed (by Pang the Naga). If the kidnap victims have not been rescued, the PCs could use the ship to visit the ruins at 8. At the conclusion, Bomoch will arrive to announce that the Keth of Broken Jaw is Keth no longer, but the new Rajjor of the Goblins, for whom a battle of liberation awaits. Appendix: The Jade Queen's Trials If the PCs undergo the Jade Queen’s trials (4), the Referee can arrange for them to predict future fates.

Commentary Did I do this in 30 minutes? No. A sketch map and keying the locations took 30 minutes but then I went back and created all those tables for the rumours, omens, incidents, etc. So as far as '30 Minute Dungeon Challenge' goes it's a bit of a cheat. Never mind. If you're going to do a linear story like this, it stands or falls on the details that makes it feel compelling rather than limiting. Hopefully, this tale of down-trodden goblins learning their royal birthright and rising up against their colonial masters has some resonance. There's some nice mysticism in the forest and I tried to get across a sense of omens being fulfilled. The whole idea of native 'heroic' goblins and evil 'imperialist' elves turned up in a mini-campaign I ran last year, but there it was a romantic orc confederation being conquered by elves, with their vaguely Aztec human servitors. The routed orcs had to retreat into their swampy heartland and discovered truths about their origins and foundational myths along the way. I wanted to avoid clumsy Native American comparisons (despite the name alluding to Wounded Knee) and give the goblins a sense of cultural texture, so I located this in a South East Asian (specifically, Malaysian) setting. If you want to give the goblins some linguistically appropriate names, here's a quick table: I didn't provide any stats for the hideous Cockatrices (they turn you to salt! they're frightened of weasels!) and the floating-head-undead Penanggouls. These horrors are just there for texture and chills. If you really want the PCs to fight them (why would you want that? why?) then Cockatrices (minus the weasel stuff) are in the D&D Expert rules/Monster Manual or Basic (Holmes) p23 and Penanggalans are in the AD&D Fiend Folio (or else treat them as Wights). In Forge, use Basilisks as Cockatrices and the characteristics of Nagdu for Penanggouls.

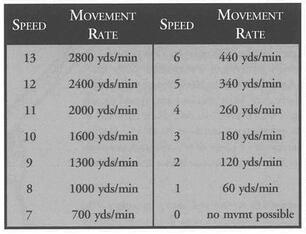

One of the distinctions that divides fans of different editions of D&D is the question, 'How long is a melee round?' Some lexical detective work is needed to figure out what D&D originally intended. Back in 1974, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson explain (in the Underworld & Wilderness Adventures expansion) that a 'turn' is ten minutes and there are 10 1-minute melee rounds in a turn. Gygax retained the 1-minute melee round for 1st and 2nd edition AD&D, justifying it like this: The 1 minute melee round assumes much activity – rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on. Once during this period each combatant has the opportunity to get a real blow in (1st ed. AD&D Players Hand Book, p39) The 1-minute round seems to have its roots in the wargaming superstructure that D&D emerged from. One minute allows a squad or battalion to move, line up, fire, generally 'take their turn'. Combat in wargaming is typically all-or-nothing, so in that 1-minute of action you might completely eliminate your opponent. Adapting this to tabletop RPGs produces a high level of abstraction. You're free to imagine a lot of cinematic business going on surrounding your solitary 'to hit' roll or spell. But it leads to absurdities. An armoured warrior can only manage short bursts of energetic combat, but combat in D&D can easily last 10+ melee rounds, especially in a 'cleric fight' (a fight between well-armoured characters with low damage output). That's 10+ minutes of huffing and puffing in quilted doublets, thick leather jerkins, mail hauberks... Impossible. While Gygax was working in minutes, Eric Holmes was tasked with presenting Basic D&D (1977) and unilaterally decided that the time frame for combat should be in seconds rather than minutes: Each turn is ten minutes except during combat where there are ten melee rounds per turn, each round lasting ten seconds (Basic D&D Blue Book, p9) Now that ten round fight lasts just under two minutes: much more realistic. Subsequent editions of Basic D&D - the 1981 beautiful edition by Tom Moldvay and the 1983 ugly edition by Frank Mentzer - retain this 10-second melee round. Moreover, Basic D&D charted the path that other RPGs followed. For example, Runequest defines fantasy roleplaying for non-D&D folk and hit upon a 12-second melee round. The melee round is 12 seconds long. One complete round of attacks, parries, spells, and movement happens during ascenario. (Runequest 2nd ed, p14) 12 seconds is long enough for it to eat your shield Then, in the 21st century, 3rd edition D&D switches to the 6-second melee round, which has been the standard ever since. Take that, Gygax. Holmes is vindicated! A round represents about 6 seconds in the game world. During a round, each participant takes a turn (5th ed. D&D Players Hand Book, p189) There are arguments to make both for the combat round as minute or handful of seconds. The 1-minute-round moves combat towards 'theatre of the mind' with a lot of improvised 'business' going on around the decisive blows. Tasks like picking up weapons, unsheathing swords, notching arrows, drinking potions and finding spell components are easy to fit into this stream of activity and don't penalise the character. But if you find such protracted combat unlikely, the 6/10-second-round offers a more moment-by-moment approach that suits tactical combat better, where facing and flanking matters; where you forfeit your action if you're caught unawares, if you have to ready your weapon; where it matters where you are standing and who you can see and whether you can reach somebody in time to hit them. But is it really likely that an armoured warrior can hit someone 6-10 times in a minute - or even twice that if they are high-level? Can archers really fire 12-20 arrows a minute, minute after minute? Can you really cast 6-10 spells in a minute, with combat going on all around you? The fast melee round seems to credit PCs with incredible vigour. Real Life Comparisons A medieval longbowman at the Battle of Crecy (1346) was expected to fire 12 shots a minute. That involves drawing and firing a longbow, which most people would find pretty punishing to do just the once. On the other hand, it didn't involve much aiming: longbows work because they drop a swarm of yard-long steel skewers onto the enemy, willy-nilly. And of course, this could not be sustained for more than a few minutes. A shortbow might be fired 20-30 times a minute, but, again, no one could sustain this. All of which favours the 10-second melee round more than the 6-second one, which allows a bow to be fired up to a dozen times. Moreover, how many arrows actually get fired in a 1-minute round? If the round assumes lots of 'shots' which only pin the opponent down or harry them, but include a couple of 'true' or 'effective' shots that have "the opportunity to get a real blow in", it's reasonable to assume an archer fires at least half a dozen arrows per minute, probably twice that. An archer with a quiver of 20 arrows will have fired all of the after a couple of 1-minute melee rounds. Jogging speeds in minutes and seconds Usain Bolt's world record is to run 100m in 9.58 seconds. That's about 200ft in 6 seconds or 330ft in 10 seconds. The average jogger covers 70ft in 6 seconds or 120ft in 10 seconds or a whopping 730ft in a minute. Now if we halve that 'jogging speed' for someone running in heavy clothing, carrying adventuring gear, in a darkly lit tunnel, over uneven and slippery floor, you probably get 35ft in a 6-second melee round or 60ft in a 10-second round and let's say 360ft in a minute. But it's even worse in heavy armour, carrying a sword, trying not to get killed. Even if we assume adventurers are trained to run around in armour, 35/60/360ft per round has to be the maximum and a more likely distance is 20ft in 6 seconds or 30ft in 10 seconds and 180ft in a minute, which is walking speed. 1st Edition AD&D (PHB p102) allows unarmoured characters to travel 120ft in a 1-minute round, which suggests a very cautious sort of walk. Halve that for characters in metal armour, which is a weary shuffle. D&D 5th edition has an unencumbered human traveling 60ft in a 6-second round, which is rather speedy, more like an actual jog along a smooth pavement. Basic D&D (Molvay or Mentzer) has unencumbered characters jogging 40ft in a 10-second round and lumbering 20ft in metal armour, which is comparable to AD&D speeds. Holmes Basic D&D allows 20ft movement in a melee round, 10ft if armoured, which is almost immobile by comparison. One of the less-remarked aspects of the development of D&D through the editions is how much faster everyone is now. A combat minute in Forge Out Of Chaos Indie RPG Forge confesses its derivation from D&D (especially 1st edition AD&D) in myriad ways, but its adoption of the 1-minute melee round is one of the clearest. After all, who would come up with such a profoundly un-intuitive gaming convention on their own? But Forge imports some ideas from other RPGs that sit uneasily with the abstract 'melee minute'. For example: armour. D&D treats armour as an impediment to hitting which works fine in a melee minute, where it's assumed your opponent takes lots of swipes against you and armour merely shifts the odds of being hurt in your favour. In 1978, Runequest took another direction, with armour deducting from dealt damage, which works well with its more simulationist 12-second round, in which combatants deal each other single bone-crunching blows. Forge tries to have it both ways. Armour makes you harder to hit (in an abstract, when-you-average-it-all-up sort of way) but also absorbs the damage dealt (in a specific that-blow-didn't-get-through sort of way). However, Forge usually inhabits the theatre-of-the-mind world of AD&D combat, where miniatures and battle maps are optional because positioning and facing barely matter. In Forge, you're either attacking an enemy's DV1 (including shield and Awareness bonus) or DV2 (no shield, no Awareness bonus) and there's nothing more specific than that. At least AD&D perversely factored in whether you were making a flank attack on someones shield-side or not (forgetting, temporarily, the rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on of a melee-minute). But then Forge also forgets its melee-minute time frame when it obsesses about the range of magic spells and invites you to 'pump' spells to increase the range. Who cares what the range is when the spell is being cast in a busy minute in which you can dash over 100ft to get close to someone? Back in Holmes Basic, when a Magic-User might jog 20ft and an armoured Elf lumber 10ft, spell range mattered. Forge bases movement on the Speed (SPD) characteristic, determined for PCs using 1d4+1 (2-5). 'Yards' is an oddity: all the spell ranges are in feet. It's probably an unedited error and I'm always happy to enforce the convention that yards apply outside the dungeon but once you're underground, all yards count as feet. Forge also lacks any rules for encumbrance (but I offer house rules), so we have to assume these distances apply to unarmoured, unencumbered characters. If SPD 3 is the human norm, then adventurers are moving around much faster than in AD&D. If we apply AD&D logic, then characters in non-metal armour lurch about at 3/4 this speed and metal armour in 1/2 this speed. Nonetheless, if you've got SPD 5 then, even in plate mail, you will cover an impressive 170ft in a melee minute, much faster than AD&D. (I'm not even going to get into the whole conceptual muddle about whether SPD is supposed to represent reflexes or brute strength, the latter of which matters more for hauling yourself across a combat zone in armour.) If you can cover this sort of distance in a melee-minute, you don't worry too much about the range requirements of bows (which Forge also dispenses with) or spells. You just jog until you're close enough to your opponent and ZAP! Does anybody use melee-minutes any more? Gary Gygax ported the concept of the melee-minute into AD&D and Forge cloned it in an unreflective moment, but neither game really gets to grips with the implications. Gygax links his melee-minutes to another of D&D's defining concepts: Hit Points. What does it mean for a high level character to amass Hit Points sufficient to endure any number of sword blows? They haven't increased in literal physical toughness, but rather such areas as skill in combat and similar life-or-death situations, the "sixth sense" which warns the individual of some otherwise unforeseen events, sheer luck and the fantastic provisions of magical protections and/or divine protection (Dungeon Master's Guide, p82) In other words, some 'hits' in combat aren't even 'hits' at all. They're like the lost lives of a cat. The axe whistles through the space where your head was a moment ago, but some instinct made you duck. You lose Hit Points, representing pushing your luck, but you're physically unharmed. Yet, in another mood, Gygax is devoting pages in the Dungeon Master's Guide (e.g. pp52-3, 64, 69) to tactical movement, as if he were offering rules to a skirmish game with the action paced out in heartbeats, forgetting that all this is redundant in a rules set where, each minute, characters move great distances ("rushes, retreats") and the 'to hit' roll represents shaving away your opponent's luck rather than actually stabbing them. You can see why later editions of D&D followed Holmes down the heartbeat route of melee-moments rather than melee-minutes. Yet it leaves D&D with the preposterous institution of Hit Points, now bereft of its only justification, that a damaging 'hit' in combat doesn't necessarily involve any physical contact. If D&D can't square the circle of melee-time, then I can't 'fix' Forge's hybrid concoction either. In Forge, Hit Points are calculated from Stamina and don't balloon as you gain experience: a 'hit' in Forge is clearly something that leaves cuts and bruises. You use binding kits to regain your Hit Points, which you wouldn't do if all you'd lost was some good luck. In Forge, armour absorbs damage: if the armour deteriorates, then surely the axe did hit you! The long melee-minute loses its rationale. If I convert to the 'melee moment' approach - and I like the feel of Holmes' 10-second melee round - then all of Forge's spells last way too long and there's no point in 'pumping' them for extra duration (although extra range might become relevant again since unarmoured SPD 3 characters would only move 60ft per round or 30ft in plate mail). We can at least be consistent about the melee-minute approach. There doesn't seem to be anything to be done about the weirdness of two-handed swords which get swung once every two minutes. The convention comes from Holmes, with his snapshot 10-second rounds. Gygax did away with it in a moment of lucidity, but Forge ports it straight back in because it's really hard to make yourself remember that your melee rounds last an entire minute! Keeping track of arrows fired during a melee-minute seems irrational. In that space of time, an archer will fire almost all her arrows, then gather up the fallen ones to fire again. To represent depletion, just house rule that the archer's quiver goes down by 1d6 arrows every round, representing shafts that cannot be easily recovered. Then, at the end of the battle, the archer gathers them all back, minus a few lost or broken ones (perhaps, reducing the total stock by 1d6). In this sort of time frame, combatants can reach just about any area of the battlefield that their (rather large) movement allowance permits. Forge is onto something by treating tactical positioning as a simple DV1 (they saw you coming) vs DV2 (they didn't, or they're engaged in combat with somebody else). Place your miniature wherever you want to be on the battle map at the start of each melee minute. Or dispense with miniatures altogether! OSR dungeoncrawling without miniatures? I think I'd better think it out again...

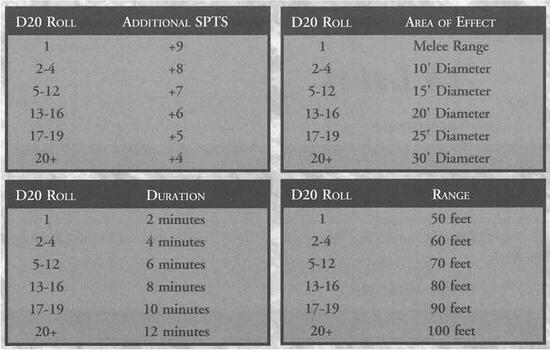

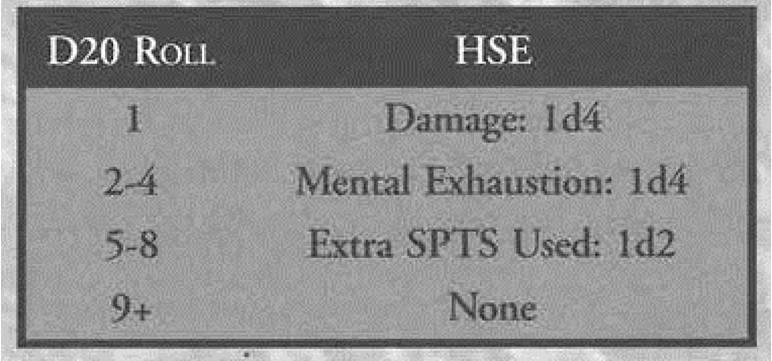

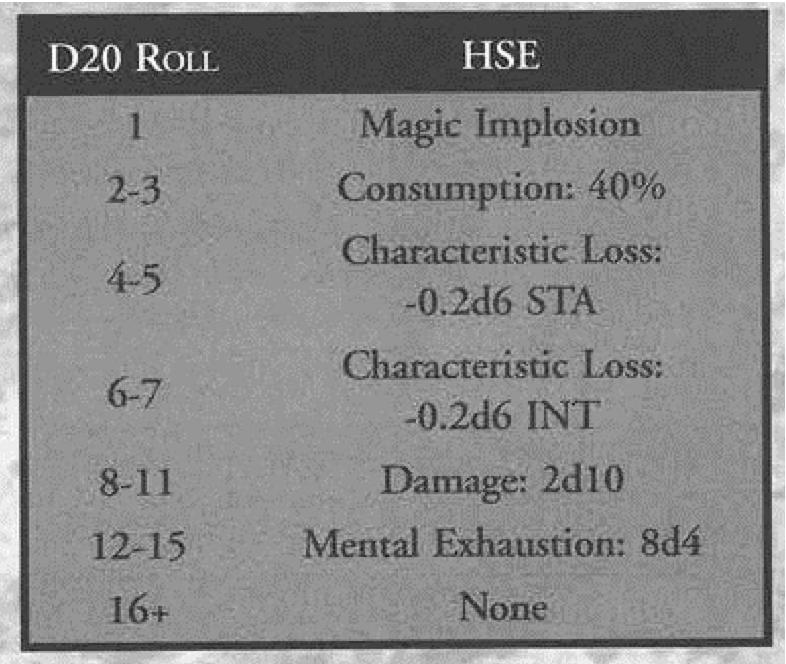

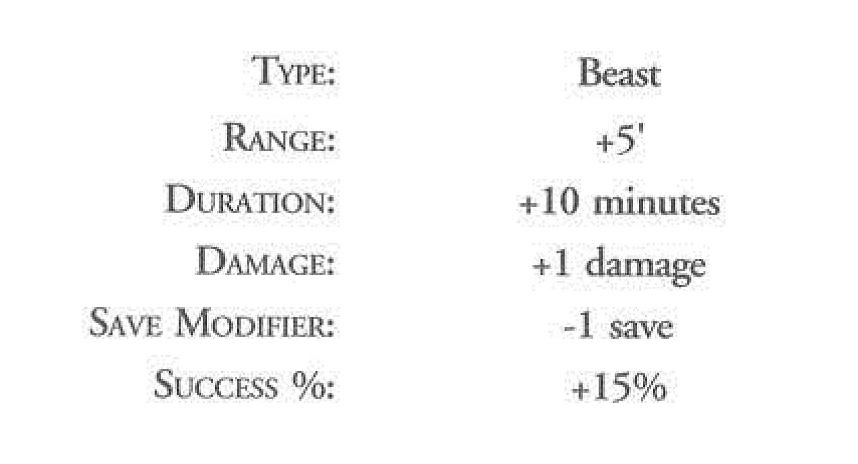

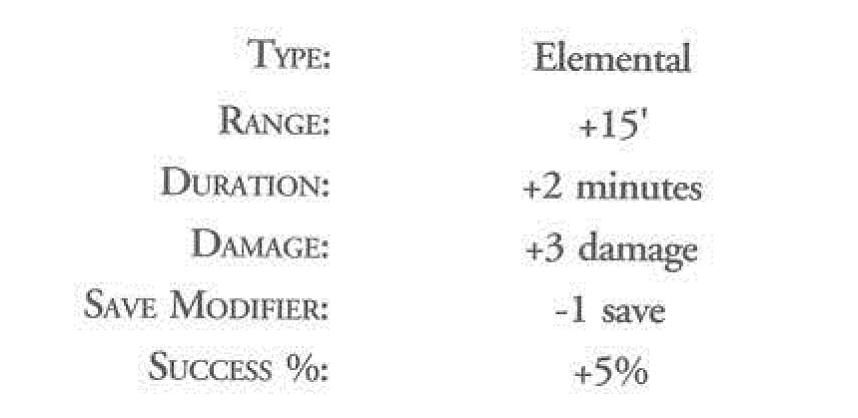

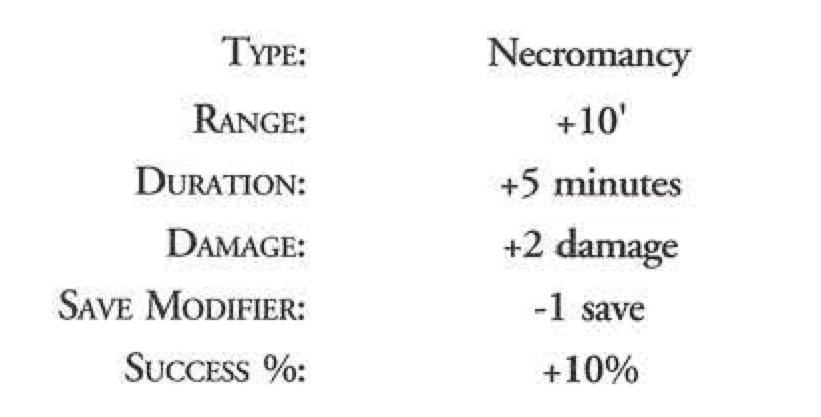

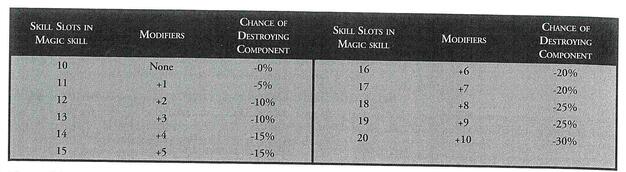

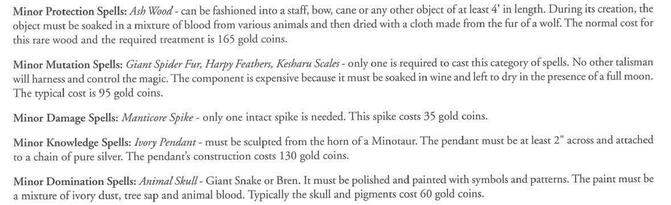

In Forge Out Of Chaos, Divine Magic (as previously examined) is straightforward: 10 skill sots and zap: you're imbued. Pagan Magic is different. Once upon a time the gods bestowed it on mortals, but no longer (what with them all being dead or banished). Instead, mortals have figured out how to make magic work without the assistance of divine patrons. It includes quick'n'dirty 'Attack Magic': Beast Magic (animal powers), Elementalism (everything from fireballs and flying to water breathing) and Necromancy (creating and controlling undead and, naturally, curses). This makes Pagan Magic a bit like fantasy world technology. It's the manipulation of impersonal (super)natural forces through intelligence, applied technique and special tools. It's much more bespoke than Divine Magic and you can bend it till it breaks. It's also less reliable and can backfire. Return of the schematics 'Schematics' are tables that introduce variable elements for every spell: is the duration as low as 2 minutes or over 10? does the enemy get a Saving Throw at +2 or at -2? Divine Magic enables you to use of spare spell slots re-rolling already-acquired spells in the hope of improving their variables. Pagan Magic adds a few twists to this. First of all, Mages can choose to sink more than the basic 10 skill slots into their Magic skill. Each extra slot adds +1 to a die roll on the schematics for each spell. So if you invest 13 skill slots into Magic, you get a +3 bonus to spread among the schematics for each of your spells. You will need it, for several reasons. Unlike Divine Magic, Pagan Magic lets you acquire spells that are a level higher than your skill. This means, with 1st level Magic you can learn 2nd level Attack Spells. However, you get a -2 penalty on every roll on the schematics for a spell that's higher than your current level. The extra investment offsets this. (Of course there are other reasons to be cautious about learning higher-level spells. They cost a lot of Spell Points to cast. A typical Mage has 20-25 SPTS and a 1st level Elementalist spell costs 9 SPTS to cast; a 2nd level spell costs 18 SPTS, which will just about clean you out.) These spells come with Harmful Side Effects (HSE) and every spell forces you to roll on the HSE schematic to see what happens when you cast it. You probably get 'nothing' but HSEs can include taking damage every time you cast that spell, spending extra SPTS just to cast that spell or finding yourself unable to perform magic for a period after using the spell. Higher level spells are much more unnerving. The rules fail to clarify a couple of points. Presumably the mystical, un-healable Damage is 'actual' damage (it comes off Hit Points directly, ignoring armour). How long does the Mental Exhaustion last? Minutes, hours or days? That's harder to call, but most of the durations used in Forge's magic system are in minutes, so let's assume that's what is meant. If you're going to use that extra-investment bonus on any schematic, I think HSE will probably be the one. 'Pumping' spells The other thing Pagan Magic can do is crank up the intensity. 'Pumping' a spell means spending extra SPTS to get a better-than-normal result. The exact result depends on the type of Magic you specialise in. As you can see, you get a big boost to range or damage when 'pumping' Elemental spells, whereas Beast spells get a better boost to duration and chance of success. Necromancy's in the middle. The precise cost of 'pumping' a particular spell is determined by another schematic. This schematic is a tempting candidate for that extra-investment bonus, since the cost typically varies from as low as half-as-much-again to outright doubling the base cost of a 1st level spell in SPTS. However, the costs of 'pumping' a spell don't go up with levels: 'pumping' a 4th level spell cost the same as 'pumping' a 1st level spell, so you might be happier bearing the cost with high level spells (you'll have tons of SPTS by then anyway). Before you get carried away and run around 'pumping' every spell for extra damage or tougher saving throws, a warning: there's a chance any 'pumped' spell blows up in your face. The chance of this is a whopping 25%, plus 5% for each extra 'pump' you risk and plus/minus 5% for each difference in level between your skill and the spell itself. So if you've got 2nd level Magic and you pump a 1st level spell 3 times, you've got a 30% chance of it going BOOM (25% + 10% for the 2 extra pumps - 5% for the difference in your favour). Remember how you could invest extra skill slots in Pagan Magic? Well, they reduce your vulnerability to backfiring spells: So if you invested 3 extra skill slots in your Magic skill, you not only get a +3 bonus on the schematics, but you deduct 10% from the chance of spells backfiring when you 'pump' them. Sweet. If the spell backfires, it doesn't just fizzle out. You take damage based on the spell level and the number of 'pumps' you put into it, times two. If that 1st level spell backfires after being pumped 3 times, you will take 8 damage - 8 'actual' damage, which could quite possibly kill you. If that wasn't bad enough, your spell component disintegrates too. Spell components The only thing required for Divine Magic is a prayer, but because Pagan Magic is 'tech' you need special equipment for it: spell components. No components, no spell. That's the component list for Beast Magic spells - the 'minor' ones (levels 1-4). 'Major' spells (levels 5-8) need even fancier gizmos. Since a Player Character starts with 30-180gp (good ol' 3d6 times ten), and you probably want a weapon and some basic armour, most Mages will start out their adventuring career with just a single spell component (i.e. that Manticore Spike for damage spells). They might 'know' other spells, but they're not able to cast them until they can afford the kit. This gives starting Mages a very strong reason to go dungeoncrawling and provides the Referee with 'treasures' that players will appreciate: finding an Ash Wand, already "soaked in a mixture of blood from various animals," will be worth more to some players than a magic sword. (Of course, maybe the campaign setting has Mage Guilds that kit out starting PCs with all the Ash Wands and Manticore Spikes they need, then extract the costs back from them with massive interest rates...) Since components have a nasty habit of going BOOM when you 'pump' spells, wealthy adventurers will invest in spares! That's another reason why Forge really needs an Encumbrance system. Let's reflect Forge's magic system was widely praised - indeed, it was its only saving grace, for many critics. It certainly offers players a lot to think about during character creation:

Once your character is up-and-running, you have to 'curate' your spell collection:

Curating your spell collection like this is very satisfying. It means that even if another player has a Mage with the same type of Magic, its unlikely they have the same spells as you and, even if they do, it's unlikely their spells have quite the same variables as yours. Your spell collection is your achievement and you can feel rightly proud of it. The only problem with all this is for the Referee: throwing together a NPC Mage is not a trivial chore. I'm a bit doubtful about 'pumping' spells to boost Duration or Range. Most spells last 10-20 minutes anyway and it's hard to think of situations where that's not enough but adding 5 or 10 minutes would make all the difference. Perhaps with Beast Magic, where pumping could add 10 or 20 minutes, you might enable a helpful shapechange spell to last a couple of encounters. Boosting Range sounds like a useful thing, but in fact not so much. With it's weird 1-minute melee rounds (more about that nonsense in another blog), Forge characters can cover hundreds of yards in a couple of rounds, so there are easier ways of bringing a target into range than 'pumping' a spell. The range-boosts just aren't big enough to make it tempting in the absence of crunchy tactical movement in the combat system. Types of Attack Magic: Beast, Elemental, Necromancy Pagan Magic also includes Enchantment, which follows all the rules above but adds some tricks of its own. I'll cover that another time. Just now, I want to finish off with a comparison of the three schools of Attack Magic. Beast Magic is certainly the easiest, costing just 7 SPTS per spell level; Necromancy costs 8 and Elementalism 9. This makes Beast Magic favourite if you rolled low in Power (hence, low in SPTS). Each school offers similar offensive spells. There's a ranged spell that deals automatic damage, no roll 'to hit': Beast Magic's 'Spike' deals 1d6 damage, Necromancy's 'Skeletal Bolt' deals 1d8 and Elementalism's 'Ice Bolt' deals 1d10. You see the progression? There's a 2nd level version that deals twice as much damage and so on. Very balanced. There's also a close combat spell that requires a successful roll 'to hit' (using your Magic skill against DV2 instead of Melee Weapons) but deals 'actual' damage, bypassing armour: Beast Magic 'Wounding' deals 1d6, Necromantic 'Pain' deals 1d8 and Elemental 'Fiery Touch' deals 1d10. The 2nd level iterations double this damage too. This makes it tempting for Elementalists in particular to 'pump' their damage spell twice for +6 damage; 1d10+6 damage (Ice Bolt or especially Fiery Touch) has a decent chance of killing a humanoid character outright. 2d10+6 damage (2nd level Ice Burst or Searing Touch) will kill tougher things. Shame about the 30% chance of backfiring (35% for the 2nd level version) but if you invested extra skill slots in Magic, you could risk it. Let's face it, you will risk it. Beyond this, the schools vary in content. There are defensive spells of different types and a whole bunch of utility stuff. Beast Mages can influence and talk with animals and acquire animal abilities (climbing like spiders, hiding like chameleons) and shape-changing powers; Elementalists can create fire and wind, walk on water or levitate; Necromancers can turn or create undead or imitate their powers and immunities. Since you get a check to your Magic skill every time you cast a spell in a crisis situation (i.e. adventuring) and you're limited to casting spells until your SPTS run out (so perhaps 3 or 4 times in an adventure for starting characters), you're going to advance slowly in Magic at first. Higher-level casters can speed advancement by heavily using low level spells. Maybe consider buying some Vigoshian Root? A boost of 10-60 SPTS for an hour lets you go nuts with those Ice Bolts. Yes, it costs 30gp and yes, there's a 50% chance you will lose 0.1d3 Insight. But magic is all about trade-offs, right? Necromancy introduces an interesting mechanic. Each time the Necromancer animates a new Skeleton (1st level) or Zombie (2nd level), they lose 0.1 Stamina permanently. As Stamina drops, so do Hit Points. Raising the undead is not to be done casually. The 7th level spell 'Life Drain' lets you reverse this, permanently stealing decimal points of Stamina from victims to replenish your own (which should be pretty far depleted by then). But remember 7th level spells require 13+ Insight and you will need 26%+ on your base Magic skill if you're ever going to advance that far. If manufacturing undead is your thing, the 4th level spell 'Bestow Intellect' drains 0.1 Intellect from the Necromancer to grant created undead some dog-like autonomy. After that, you can teach them your skills, project your voice through them, deputise them to command your other mindless undead, generally have fun curating your collection of skellies and zoms. Beast Magic has a less-thrilling variation, involving dominating animals to be your companions and bodyguards. The 2nd level spell 'Animal Domination' permanently drains 2 SPTS for each animal under your control; the 6th level 'Bestial Domination' works on giant animals but drains 5 SPTS each time. Unlike Necromancy, Beast Magic doesn't offer a way of regaining those Spell Points (except by going up levels in Magic skill, of course). With the exceptions noted above, Attack Magic spells are all short-term, usually lasting 10-20 minutes. If you want permanent magical effects, you need to try Enchantment, which I'll look at another time. There's certainly a good selection of desirable magical tricks here. Although cloned from D&D, the spell lists show clear attempts to introduce balance and allow rational progression. There's a heavy focus on combat and solutions to the sort of problems you face in dungeons. There's a lack of big area effect spells but that's an aesthetic choice: Attack Magic is low-key, personal, one-on-one. Elementalism is far and away the most potent, both as a combat option (so many damage spells, such big bonuses from 'pumping') and as utility magic (flying, talking to earth, scrying) and Beast Magic is very much the poor cousin (personal transformations, befriending beasts) but many players will be drawn to the interesting trade-offs involved in Necromancy. There are things missing: no illusions, no plant-based magic, a dearth of information-gathering spells. Nonetheless, it's a spell list that compares very favourably with Basic D&D/1st edition AD&D. However, when Forge came out in 1998, 2nd edition AD&D had already expanded the roles of clerics and magic-users and the innovations to 3rd and 4th edition in the 2000s would bring choice, balance and rational progression to D&D spell-casters. As usual with Forge, you feel that, had it come out 10 years earlier, it would have been hailed as a valuable contribution to the evolution of Fantasy RPGs. A lot happens in a decade.

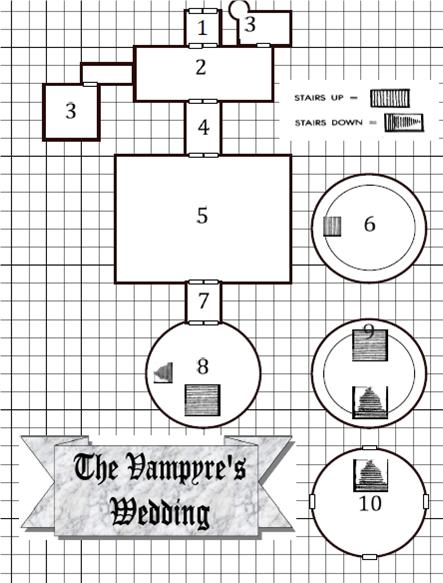

The Vampyr's Wedding is a 30-minute Dungeon Challenge, as set out by Tristan Tanner in his Bogeyman Blog. I hope it will inspire other people to create some of their own and send them to me - so I can hand out free copies of Forge Out Of Chaos as prizes in the January 2020 competition I used Tristan's optional tables to create an extra discipline for this 10-room dungeon: empty rooms that point to a combat, reveal history and offer something useful to PCs; the special room provides a boon for a sacrifice; the NPC is a rival; the combat encounters are a horde of weaklings, a pair of toughs and a tough boss; the traps are inconveniencing and incapacitating. BackgroundThe Margrave of Strigovia, a renowned necromancer, has sought the hand of Dajmira the Duchess of Marusz. Furious at being rejected, he has become a vampyr and vowed she will join him as his undead bridge. Hook The vampyr Margrave of Strigovia has kidnapped the Duchess from her carriage along with her ladies in waiting, slaughtering her royal escort. He holds the Duchess at his tower and at sunset will consummate their wedding by making her a vampyr too. Only you can prevent this blasphemous union by storming Karnstein Castle, his fortress guarded by his loyal Stygani retainers. It is noon and time is running out. 1. Gates to Castle Karnstein Breaking the gates down is successful rolling 1 on a d6; two characters can attempt this per round and Strength bonuses apply (Forge: locked, 12 structural points). A crossbowman from 3 will fire at characters through the arrow slits. The corridor beyond has similar gates at the far end (Forge, 10 structural points) and more arrow slits, allowing both crossbowmen to fire. 2. Guard Room Tables and chairs are set about for a group of Stygani tribesmen who serve the Margrave with fanatical loyalty. There are a number equal to the number of PCs (plus their henchmen) added to 1d6.

They are unarmed and relaxing, but will arm themselves when the PCs start to break down the doors from 1:

3. Sentries Two Stygani guards, Fennix and Leshi, watch from the turret in the corner. Armed with crossbows, they will fire on intruders. Even if the PCs surprise the guards in 2, these crossbowmen with emerge from here to fire on the PCs. Otherwise they will listen to the battle and only join in after 6 rounds if the guards have killed a PC. Otherwise, they will hide here and surrender to the PCs. They are too frightened of the Margrave to venture further into the castle.

4. Prisoner Ilsa Gellhorn, the Duchess’ lady-in-waiting, is tied to a chair and gagged, but conscious and clearly terrified. She bears a vampyr’s bite and has been told that she will become undead once the sun sets. She will join the PCs because she is desperate to prevent this.

She has no combat skills but is brave and resourceful. Ilsa will conceive a romantic attraction to one PC (roll randomly or choose highest Charisma or one who speaks kindly to her) and demonstrate this by staying close, trying to hold their hand, asking if they are married and showing excessive concern they are not harmed. Her vampyric infection makes her immune to poison (e.g. the toadstools in 5). 5. Courtyard of Decay The courtyard is open to the noonday sky and provides a view of the Margrave’s Tower to the south. It is madly overgrown with weeds and many lurid red toadstools. There are also unburied bodies: the Duchess’ guards and other doomed adventurers. Searching the corpses will find these useful treasures (roll 1d6, rolling a duplicate means finding nothing):

6. Pit of the Vampyrs PCs who succumb to the toadstools in 5 or the trap in 7 wake up here hours later (see 9). The pit is surrounded by a walkway, 10’ overhead, and a staircase rises from the walkway and through the ceiling. The PCs have stripped of weapons and drained to 1HP by hungry but decayed vampyrs in the pit: withered men and women, some only children, all mindless with hunger and only able to nibble a small amount of blood at a time. They can be shaken off and kept at bay with weapons for 2d6 minutes (or 1d6+6 using torches), but when they attack it will be in overwhelming numbers. There are four ways for PCs to escape:

At least one of the PCs is now infected with vampyrism. Ask the PCs to volunteer themselves by writing infected or non-infected on a slip of paper and revealing simultaneously; if no one writes infected then all the PCs have been infected. Vampyr PCs can bite in combat for 1d3 damage (or +2 damage if they already have bite attacks) and regain 1HP for each successful bite attack; they can regain 1d4 HP by feeding from characters that die in combat. They cannot benefit from healing magic or be affected by poison. 7. Gates to Karnstein Tower These doors are stiff and rusty but not locked. Above the inner door is the Margrave’s family crest (a book and a chalice on either side of a two-headed eagle) and the family motto: ‘Learning the Arts of Darkness / To Defeat the Servants of Darkness.’ A pit trap in on the floor opens, dropping everyone in the corridor down a chute and into the Pit of Vampyrs (6), inflicting 1d6 falling damage (cushioned by landing on bones and corpses). 8. Tower - Ground Floor A stairwell descends to the Pit (6) and a staircase rises to the balcony (9). Paintings on the wall depict the Margrave’s ancestors, including his great-great-grandfather Vaclav the Great who slew the Spectre of Strigovia. Historians will know that the Margraves originally took up necromancy to defeat the undead, not join them. There are Stygani guards here in the same state of unreadiness as 2: they are equal in number to the PCs (plus henchmen like Ilsa, Fennix or Leshi). 9. Tower - Balcony Locked windows give views of the evening sky. In the west the sun is setting with 10-15 minutes until dusk. The Margrave’s two lieutenants guard the staircase that rises to the top of the tower. They are tough undead upyrs (intelligent ghouls who can move around in the sunlight) named Radu and Mircea. Radu fights with his ghoul claws and bite but Mircea wields a two-handed war scythe.

10. Tower - Upper Floor This room has a staircase that descends to the balcony (9). There are windows in the north, east and south walls that are open to the evening sky. The west windows are closed and covered by a heavy drape. Beside the west window, the Margrave is marrying the Duchess, who is enchanted and not resisting. The minister is a robed demonic figure conjured from the Netherworld that will not intervene in any battle. The Margrave will attack anyone who interrupts his wedding. He summons a swarm of bats to buffet and paralyse anyone trying to open the drapes. After 6 rounds of combat, the sun sets: the Margrave breaks from combat, leaps over to the Duchess and takes her in his arms; on the next round he drains her of blood as the curtain falls, revealing a ruddy glow of dusk on the western horizon. The Duchess becomes a vampyric upyr (same stats as Isla, below) and joins the fight after 1d4 rounds.

The PCs have several options:

If Ilsa is present, she becomes a vampyric upyr after 1d4 rounds of combat.

Ilsa the Upyr will attack the PCs unless the object of her affections either pleads for her humanity or is harmed by the Margrave, in which case she will attack the Margrave instead. PCs who disengage from combat can appeal to the demonic minister to halt the wedding. He might do this if they offer him something more appealing (and horrible) than turning the Duchess into a vampyr. If the Referee approves, the demon agrees and the Duchess’ enchantment is broken. She pulls down the drape and leaps from a window, killing herself and transfixing the Margrave in sunlight. Commentary I'm legitimately proud of this one since it took 30 minutes to write - of course I then went through adding in the stat blocks and conversions and created the map. It's a two-step scenario. The first act is a fight-and-explore dungeon with some nice magic items and possible allies to discover. Then the PCs end up trapped, must escape and it becomes a race against time. If the PCs choose to become vampyrs then they can feed from the Stygani guards in 8. The Margrave is a tough opponent and if the sun sets he will overwhelm the PCs easily. The trick is to open the drapes. Potentially, PCs could unlock the casement windows in 9, climb up the outside of the tower and tear down the drapes from the outside, giving them 6 whole rounds of sunlight to attack the helpless, burning Margrave. That's optimal. If the PCs rush up the stairs, they have a difficult fight and anyone approaching the drapes gets driven back by bats. PC options are listed in room 10 but the players might come up with others, such as setting fire to the drapes or sacrificing themselves by leaping out of the window, taking the Margrave with them. Even once transfixed by sunlight, the Margrave doesn't automatically die and if the sun sets while he's still alive, he becomes a fully empowered vampyr with all his powers (in D&D this includes regeneration; in Forge, a selection of Necromancy spells). The scenario is designed to offer the players ideas and allies in the first act that they can use in the second. It might be important to recruit (and not stake!) Ilsa and to realise the Margrave comes from a noble lineage of undead-hunters. Hopefully, the sunset showdown can be an occasion for dramatic roleplaying as well as dice-rolling. Sharp-eyed followers of this blog (if any there be) will notice that the setting of this scenario is not what was originally proposed. Back when I set out my 6 30-Minute Dungeon Challenges, I named the vampire and his bride after Persian cultural forms; in this version, they're German/Slavonic. I love the idea of a Persian vampire story, but the brevity of this scenario means that the archetypal Bohemian setting makes for easier hooks. Plus, the vampyr's title is a 'Margrave' which is too good a pun to miss.

I've spent time looking at the apocalyptic mythology set out in FORGE OUT OF CHAOS, as a basis for its system of Divine Magic, an explanation for its races and clerical classes and its (rather overlooked) implications for fantasy world-building. Time now to take a deep dive and explore the mythology on its own terms. Just what are its values and themes? After all, a myth, even a careless and derivative myth, is a tightly packaged bundle of meanings - it's an answer in story form to the fundamental questions of existence. So what answers do the myths of Enigwa's creation, the war between Berethenu & Grom and the Banishment provide? Tolkien & Kibbean Creation Myths

The Kibbe Brothers have clearly taken points from Tolkien. For example, in The Silmarillion (1977), Tolkien sets out the Ainulindalë (the Music of the Ainur) and Valaquenta (the Story of the Valar). A mysterious creator-God named Iluvatar brings the world into existence. Similarly, the Kibbes introduce Enigwa as the world-creator. World-creation is a task that Tolkien's Iluvatar shares with his created servitors, the Ainur or Angels. He delegates creative power to them, but one of them, Melkor, the greatest of angel-kind, pursues his own vision, disrupting Iluvatar's harmony, to which Iluvatar responds by deepening and complicating his symphony with richer themes to incorporate Melkor's rebellion into a satisfying whole. The Ainur are then given the opportunity to enter their creation and live within it as the Valar (Powers), i.e. embodied angels or earthbound gods. In the Kibbean creation-myth, Enigwa creates the world without collaboration: "he personally forged each mountain, planted each tree, chiselled each river." He then creates the gods and inserts them into his world so that they can "explore their father's creation.". Enigwa withdraws and the gods, left with autonomy, start to develop diverging agendas. "Although most were good at heart, some became chaotic, others aggressive, still others lustful and greedy." The gods fall into discord and Enigwa has to return and unite them in a shared project. There are apparent similarities here (creator-God, lesser divine offspring, rebellious autonomy, the Creator restores harmony). Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created a myth that is purposefully analogous to the Christian one. Iluvatar is the Judeo-Christian God who creates free willed agents. He then adapts his creation to their free-willed choices, responding to their deviance with deeper and richer harmony, drawing beauty from ugliness, redemption from rebellion, holiness from hardship. Melkor of course is Lucifer, the errant angel. Tolkien's creation myth demonstrates why the creation of free-will necessitates the creation of a world, and a world which contains difficult features, but a world in which transcendent goodness is possible. The Kibbean myth is not Judeo-Christian but Darwinian. The Creator-God brings into existence, not free-willed minds, but a material world. Free-will emerges from Enigwa's absence, as rational beings explore the world through trial-and-error. It's a Behaviourist myth of learning through experience, of positive and negative reinforcement, with the gods developing in different directions, like B.F. Skinner's rats in a gigantic cage. There's no suggestion that Enigwa intends his divine children to evolve into these diverse personalities or even that he foresaw it. Although the text describes Enigwa as a "kindly father" he functions rather more like a dispassionate scientist: God-as-detached-observer. Unlike Iluvatar, he doesn't incorporate free-will and rebellion into his overall creative vision, he merely suppresses it when present and allows it to flourish when he is absent. Noxious characteristics in the world (deserts, miasmic swamps, volcanic rifts, predatory animals, parasitic wasps, diseases) are part of Iluvatar's compromise with free-will, but are outright distoetions of Enigwa's purposes, put there by his errant children. Free-willed agents don't seem to be part of Enigwa's plan so much as a surprising side-effect of it. Evil emerges from the absence of God or the failure of his foresight. In Tolkien, God's foresight is absolute and even Melkor's rebellion becomes the means by which a deeper, nobler and more surprising moral order emerges: "And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined." This distinction, between Tolkien's divinely ordered but morally complicated creation and the Kibbes' disordered and lawless creation, leads to a different conception of Humanity. What a piece of work is man In Tolkien's myth, the created world awaits the birth of Iluvatar's physical creatures, the Elves. Most of the history of Middle-Earth is the history of the Elves: their journeyings, songs, romances and craftsmanship and - later - their noble but doomed war against Melkor/Morgoth. In Tolkien's Christian imagination, the Elves represent an Unfallen Humanity, Adam and Eve's children without original sin: immortal, virtuous, the peers of angels, the icons of God. Crucially, they're not boring. Immortality and goodness are compatible with having adventures, taking risks, experiencing peril, making mistakes. The Oath of Fëanor drives some Elves to to dreadful things, but apparently without malice. Humans appear later, a sort of divine afterthought. They are mortal, frail, unlovely and lack innate wisdom. They have one thing that Elves lack: the Gift of Death. An odd sort of gift, but one that relates them more fully to the Mystery of God than the Elves and even the Valar (who are bound to the world even if their bodies are slain). Humans are a paradox: the furthest from the divine in terms of innate power, the closest in ultimate destiny. And of course, mortality makes their brief lives into possible vehicles for self-transcendence. The courage and hope and faith of Humanity exceeds anything Elves can experience. This places Humanity in a clear Christian framework: humans are simultaneously central and peripheral, exalted and lowly, the highest and the lowest of creatures. It's an insight Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Hamlet: