|

I wrote about the Detective class and adapted it for White Box in a previous blog. But I'll cover it again here before suggesting a different way of adapting it for Dragonslayer. Marcus Rowland - a stalwart of the UK RPG scene - contributed the Detective class to White Dwarf 24 back in 1981. Marcus Rowland introduces the class in these terms: The detective is a new AD&D character class whose functions are the solving of mysteries and the restoration of Law. This rather nicely fits the Detective into the mythic world of D&D, especially the Law-versus-Chaos theme of early D&D. Rowland limits Detectives to being Human, Elven, or Half-Elven, but that seems weird to me, given the Elvish link to (albeit Good-aligned) Chaos. Halfings and Dwarves are far more likely to be mystical enforcers of Law, but I would allow Half-races to dabble with Detective work, if only to allow the possibility of a Half-Orc chewing a cigar and growling 'Just one more question!' in a bad Peter Falk impression. In the world of Dragonslayer, Detectives seem to fit well as a Cleric/Monk sub-class. Rowland's prerequisites cover all six abilities, which seems too strict. If we base them on Dragonslayer Monks, then Dex 12, Int 15, Wis 12 seems appropriate, with Intelligence and Dexterity as the prime requisites for experience bonuses. Ability Requirement: Dex 12, Int 15, Wis 12 Race & Level Limit: Human U, Half-Elf 6, Half-Orc 5 (or U, if Colombo-themed), Dwarf or Halfling 7 (or U if Hercule Poirot themed) Prime Requisite: Intelligence & Dexterity Hit Dice: d6 Starting Gold Pieces: 40-160 (4d4 x10) Detectives have an attack progression and save as Clerics/Monks. Rowland lets them use chain mail and shields, but I think the Thief restriction to studded leather fits better. Any one-handed weapon is allowed: I don't see why Detectives should not use "spears, lances, flaming oil, and poison" as Rowland proscribes. This table adapts Rowland's class, with progression slightly slower than Clerics at first, but getting faster at high levels. Spells kick in at 3rd level (rather than 4th as in the original).

+ 200,000 XP and +1 HP for each level after 10th. Spells follow the pattern of clerical spells from a level lower (i.e. 5/4/3/3 at 11th level, same as a 10th level cleric) Role: Detectives are secondary fighters and scouts. Weapons & Armour: Detectives may wear leather or studded armour. They may not uses shields or two-handed weapons (except bows). Language: Detectives learn an extra language at 2nd level and every level thereafter. These languages can include Thieves Cant and Ancient Common. Saving Throws: Detectives save at +2 versus charm or emotion-control (including fear) Thief Skills: Detectives can Hear Noise, Climb Walls, Find/Remove Traps, and Appraise as a Thief of the same level. Starting at 3rd level, they can Hide in Shadows, Pick Pockets, Move Silently, and Open Locks as a Thief two levels lower. They cannot backstab. Disguise: Detectives can Disguise themselves as an Assassin. Tracking: Detectives can Track opponents as a Ranger, but only in urban or underground environments. In urban environments they must have seen the target within 2 turns (20 minutes) of commencing tracking. Underground, the chance of Tracking is reduced by 10% every time the target uses a staircase or secret door and 25% every time there is a combat encounter. Sage: When Detectives reach 10th level, they become Sages: treat as the ability to cast Legend Lore but only from his or her study/library/laboratory. By tradition, there is only one 10th+ level Detective in a city; if another arrives, the two must engage in non-lethal competition and the loser either leaves or becomes a non-adventuring consultant. Spells: Detectives gain quasi-clerical spells at 3rd level with a focus on detection and mystery solving (plus some spells aiding in escape). Like clerics, Detectives may not memorise the same spell more than once per day without use of a magical item. I've adapted Marcus Rowland's spell list, drawing in some of the Dragonslayer spells, generally making the spells a bit more impressive and abolishing expensive material components. 1st Level Detective Spells Comprehend Languages - as the 1st level Magic-User spell Date Duration: 1 round Range: 10 feet Cast on evidence (e.g. a footprint, a bloodstain, a picked lock) this spell reveals how much time has elapsed since an event related to the evidence took place. Detect Charm - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Detect Evil - as the 1st level Cleric spell (may be reversed at will) Detect Enemies Duration: 1 Turn Range: 10 feet/level The caster senses the presence of creatures who have hostile intentions towards him or herself (but not creatures that are merely dangerous to all passersby, like dangerous animals or plants or mindless undead). Detect Illusion - as the 1st level Illusionist spell Detect Lie - as the 4th level Cleric spell but cannot be reversed Detect Pits & Snares - as the 1st level Druid spell Detect Secret Door Duration: 1 round/level Range: 30 feet The caster automatically spots secret doors or secret compartments for as long as the spell lasts (and the caster may move at combat speed while the spell is in effect). Escapology 1 Duration: 1 round Range: touch The caster or the person they touch is instantly freed from ropes or simple bindings. The spell has a verbal component so the caster m,ust be able to speak to cast it. Feign Death - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Grade Metals Duration: 1 round Range: touch The caster becomes aware of all the metals that an object is made up of and their relative proportions. This allows a Detective to use their Appraise power successfully on precious metals. It does not reveal whether metals are magical, but it will detect the presence of mithril. Know Alignment - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Snare - as the 3rd level Druid spell 2nd Level Detective Spells Detect Evasions - as Detect Lies, but reveals evasions and half-truths as well as outright lies Detect Invisibility - as the 1st level Illusionist spell Detect Magic - as the 1st level Cleric spell Escapology II - as Escapology I but also works on chains and metal fetters Locate Object - as the 3rd level Cleric spell Read Codes - this improved version of Comprehend Languages translates messages in code or cipher into something the caster understands Reflect The Past Duration: 1 round per level Range: special The caster enchants a mirror which reflects events happening in the past at its location (up to 1 hour ago per level of the caster). Demons, devils, and demi-gods might notice and react to observation by this spell. Speak With Animals - as the 1st level Druid spell Speak with Dead - as the 3rd level Cleric spell 3rd Level Detective Spells Escapology III - as Escapology I but allows escape from metal boxes, riveted manacles, or otherwise 'escape proof' captivity; it also releases the target from the clutches, gluey secretions, or tentacles of monsters that trap victims ESP - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Forget - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Knock - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Speak With Plants - as the 4th level Cleric spell Suggestion - as the 3rd level Magic-User spell Truth Duration: 1 round/level Range: touch The person touched must respond to all questions with absolute truthfulness; this might require a roll to hit if the target is unwilling and not restrained and if the caster misses the spell is wasted. Only innately deceptive creatures (devils, some faerie beings, etc.) are allowed a saving throw. Ungag - as Escapology I but has no verbal components and causes a gag to fall from the caster's mouth, allowing the casting of further Escapology spells; it also frees the target from monsters which have choking/suffocating attacks Vision of the Past - as Reflect the Past but creates a 3-dimensional image in a cloud of smoke and reaches back 1 day per level. Water Breathing - as the 3rd level Druid spell 4th Level Detective Spells Escapology IV - as Escapology I but allows escape from magical prisons (such as a Maze spell) Find The Path - as the 6th level Cleric spell Maze - as the 5th level Illusionist spell, but the range is Touch and the target receives a saving throw Oracle of the Past - as Vision of the Past but reaches back one year per level of the caster; if the caster goes into a trance they receive a vision going back one century per level, but this reduces the Detective to 1d4 HP when they awaken and wipes all other spells from the mind. Polymorph Self - as the 4th level Magic-User spell Read Divine Magic - as the 1st level Cleric spell Speak With Monsters - as the 6th level Cleric spell Stone Tell - as the 6th level Cleric spell True Sight - as the 5th level Cleric spell

1 Comment

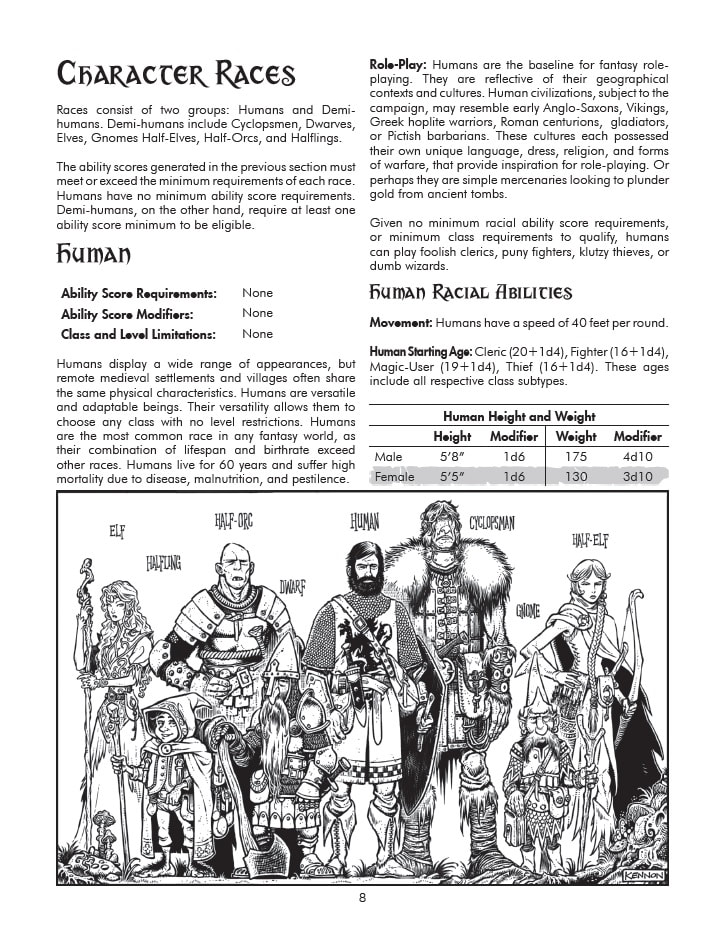

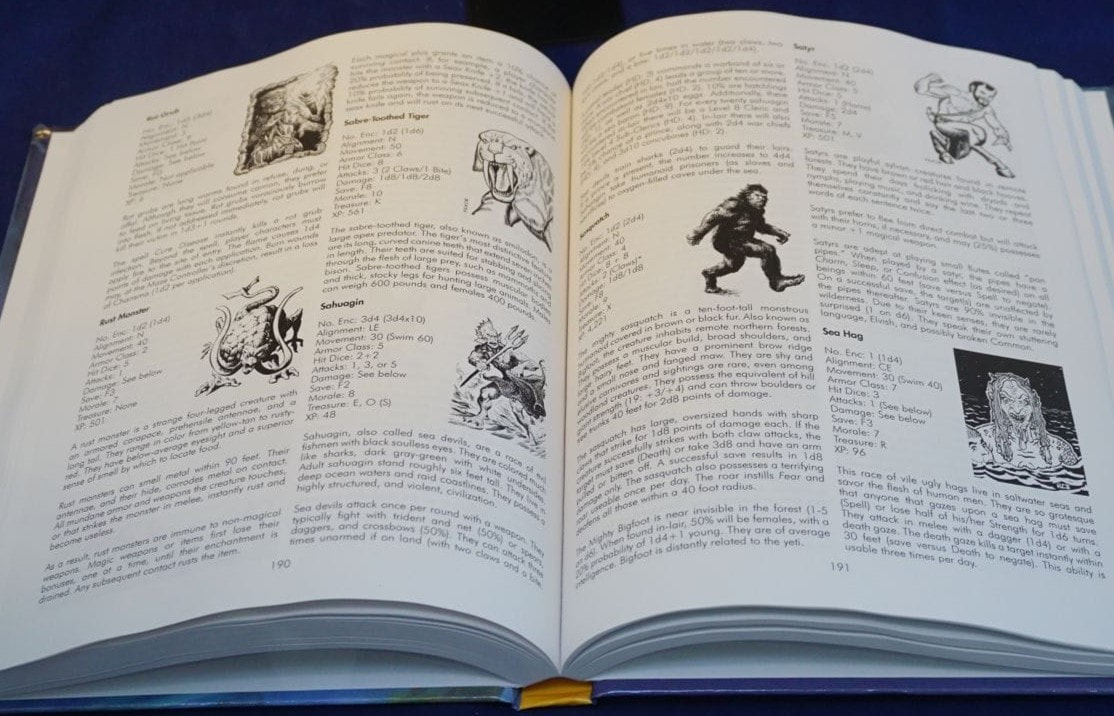

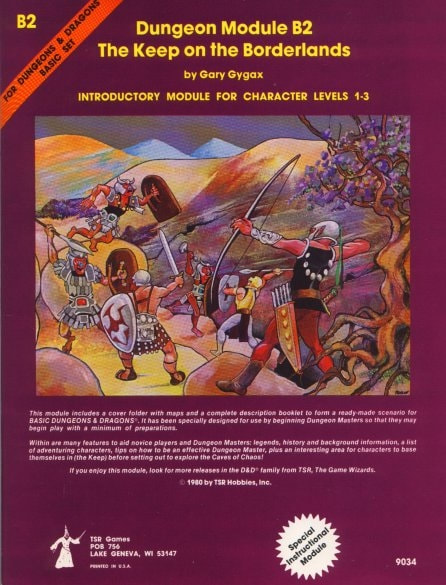

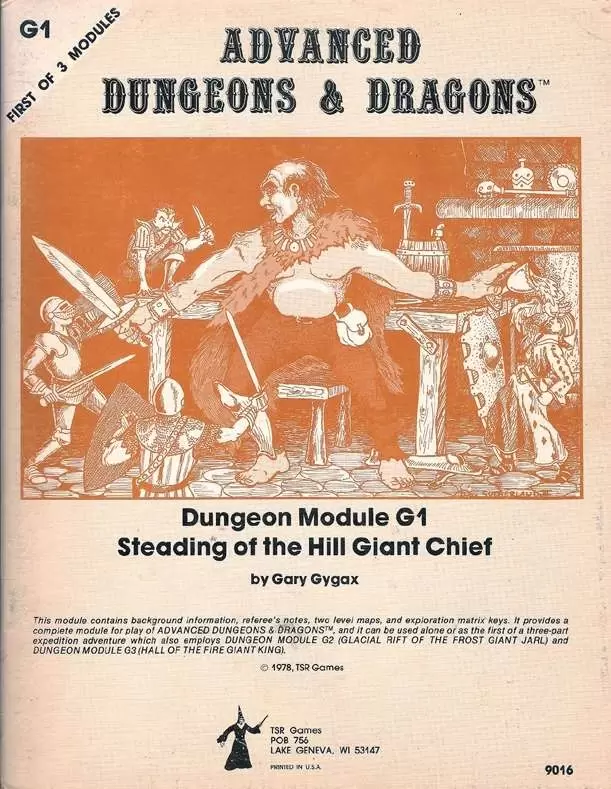

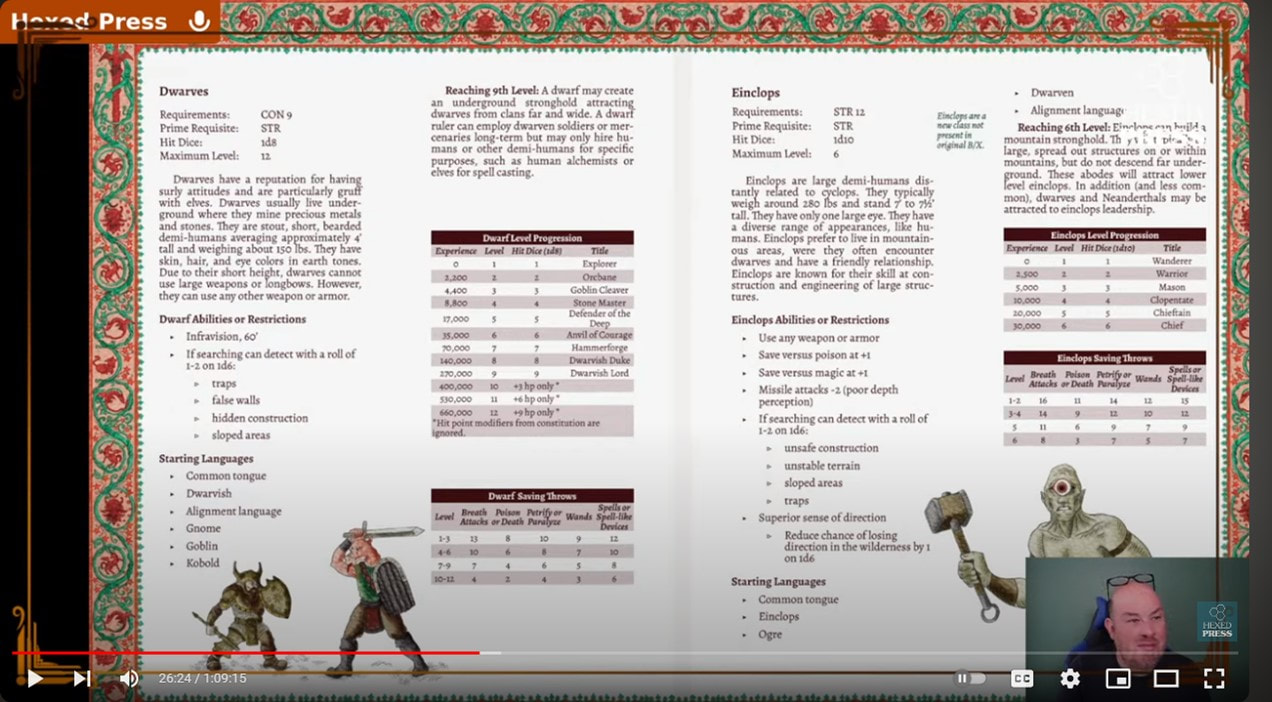

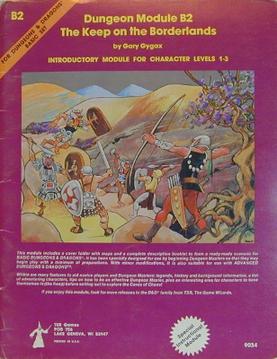

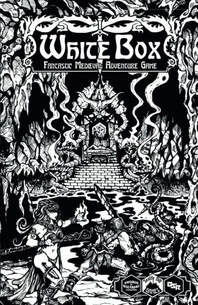

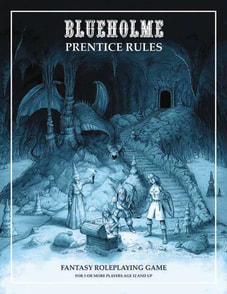

Most of us who love old school versions of D&D – or retroclones, as these rewritten versions of early D&D rule sets are termed - end up collecting them, but only using their particular favourite, if they use them at all. I’m a bit unusual, I suspect, floating between White Box Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game, Blueholme, and Labyrinth Lord. But look out, there’s a new retroclone on the block: Greg Gillespie’s Dragonslayer. Dragonslayer has its origins in the OGL Crisis that engulfed the roleplaying hobby – or at least, the OSR end of it – in 2023. You may recall that Wizards, who publish D&D, leaked a plan to revise the ‘Open Gaming Licence’ under which countless indie publishers had been creating D&D-adjacent material for 20 years. Much ink was spilled on what the original OGL did or did not permit and much speculation ensued over what new terms Wizards would impose on indie publishers. Several of the larger publishers took fright and announced plans to release their own Fantasy RPG systems that were carefully (and legally) distinct from D&D, while being fully compatible with their own D&D-adjacent products. A new generation of retroclones was a-borning, to use Stan Lee’s deathless phrase. Early out of the traps is Dr Greg Gillespie, who has become a one-man industry creating highly-regarded megadungeons. I’m a big fan of his Barrowmaze dungeon and have sent parties of adventurers into it under several fantasy rules systems. Given his investment of time, creativity, and profitable Kickstarter campaigns, in the megadungeon business, Dr Gillespie was hardly going to hand over a chunk of his profits to Wizards for the right to publish stuff based on D&D. So here he is with his own bespoke old school RPG, Dragonslayer. Whisper it: it’s still D&D really! The premise behind these retroclones has not, as far as I know, been tested in any court of law, but it wins universal acclaim in the court of public opinion, and it is this: you cannot copyright rules, only the distinctive imaginative properties those rules govern, and there’s nothing distinctive about concepts like elves, fighters, and fireballs. Therefore, Dragonslayer is really just 1980s-style D&D with certain properties removed or renamed. No mind flayers, ‘Phase Panthers’ instead of Displacer Beasts, and ‘Bigby’ has been renamed ‘Koweewah’ in all those high level ‘Magic Hand’ spells. It's more than that, though. Rewriting D&D from the ground up is a fantastic opportunity to ‘correct’ its original game's skews and stumbles and impress your own ludic philosophy on things. Old School Essentials is admired for the clean and clear way in which it assembles the jumble of rules and tables that comprise the game. OSRIC brings the mad labyrinth of AD&D together in one easily-referenced tome. Blueholme takes Holmes’s Basic D&D and extends it from 3rd to 20th level of play. Click images to link to these products on drivethrurpg The ludic philosophy is where things get a bit controversial. There are simple enough decisions to make about whether you are ‘cloning’ original ‘white box’ D&D, early Basic D&D (in its three iterations), or Gygax’s AD&D in all its Baroque glory. But some of these decisions get a bit … political. Are we going to persist in referring to Elves as a ‘race’ and capping their advancement as fighters or magic-users? What about sex-based ability caps? Your design decisions on these things are used by unkind critics to infer your viewpoint on everything from trans rights to who should have won the Second World War. As we shall see… Get On With It!To Dragonslayer, then. A single book, running to 300 pages, with striking cover art by industry legend Jeff Easley and interior art that more than lives up to the high standard he sets. It’s a beautifully laid out book, with crisp and slightly retro fonts, and materials curated to fit into single page spreads where appropriate. But then, if you are familiar with Barrowmaze and other Gillespie products, you will expect no less. It’s not cheap but you can see where the money went. Appetisers: races and classesThe introduction sets out the ‘Six Tenets of Dragonslayer’ which amount to a familiar OSR manifesto: ordinary heroes, rulings not rules, the DM (sorry … Maze Controller!) is absolute sovereign. Roll a character using the ‘Classic Six’ attributes: roll 3d6 seven times and assign as you like. Abilities follow the Basic D&D gradations (13-15 grants a bonus, 16-17 a great bonus, 18 an amazing bonus, likewise penalties for scores below 9). First level characters start with maximum Hit Points. There’s Descending Armour Class and if you’re one of those people who never understood THACO, well, I have some bad news for you later. Now for Races – and it’s old fashioned Races, not lineages or heritages or (shudder) ‘species.’ I’m British, so the R-word doesn’t connote the Satanic tang for me that it seems to have for some Americans. There are half-races here too – Half-Elves and Half-Orcs. Yes, I’m familiar with all the arguments about this. I quite admire the way Blueholme Journeymanne comes out and says: your PC can be any type of creature you like, even Thri-Keen insect people! But part of the 'old school experience' for many players is adapting yourself to the very particular imaginative contours of the game as it was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. So Half-Elves are a thing, but Half-Dwarves are not. There are some missteps, such as the big, dumb, one-eyed Cyclopsmen. Surely 'Cyclopsfolk' you say? Nope, Cyclopsmen. Deal with it. If you want to start deconstructing the game for sinister sentiments, then you start here, because these creatures are former slaves with limited IQ. They’re an unhappy inclusion (and in terms of the culture wars, a bit of an unforced error) since they have no prototype in early versions of D&D – and Half-Orcs already fulfil the big’n’brutal role. I guess they were part of Greg Gillespie’s homebrew campaign and he included them out of gratitude for the fun they brought to his table. I wonder if this was wise, given the proclivities of some critics to sniff ideological taint in things like this. The races all get randomised starting ages, height/weight tables, ability modifiers, their own base movement rates, and suggested languages for high-Intelligence characters, as well as some roleplaying hints. Darkvision is here, rather than the classic infravision, which may or may not please you. There are quirks. Gnomes have an affinity with being illusionists, so their spells last +3 rounds. It’s a bonus that will rarely make much difference to anything. Elves, meanwhile, enjoy +1 to hit with the longbow. Elves have lost their immemorial perk of being fighter/magic-users who can wear armour and cast spells. Dragonslayer seems to be a bit hostile to the idea of multi-classed characters. The concept gets a brief paragraph on p39, amounting to ‘It’s up to the GM (sorry - 'Maze Controller') whether it’s even allowed, but if it is, you get stuck with the most punitive armour restrictions of the classes you are combining.’ I’m deeply loyal to the idea of Elves in armour casting spells. My first ever D&D character (for Holmes Basic, back in 1978) was an Elf called Tristan with a Sleep spell. It seems to me there are two interesting ways to house-rule Dragonslayer. Maybe let all Elves use longbows, regardless of their character class, rather than the bonus ‘to hit’ which pretty much only benefits Elven fighters. Alternatively, let Elven fighter/magic-users wear armour (maybe limited to chain mail) – and why not let the Gnomish thief/illusionists wear leather armour while you’re at it – instead of these piddly little bonuses. But that’s just my 1sp. The character classes are incredibly well set out and the innovations here are astute. Each class fits on its own splash page, with saving throws, spells, class-abilities, and starting funds, as well as a set of ‘fast packs’ to equip starting characters. Clerics with Wisdom 15 get an extra 1st and 2nd level spell – as do magic-users with Intelligence 15+. Magic-user starting spells are rolled from an offence, defence, and a utility, with Read Magic and Detect Magic as standard. Clerics can trade in any spell they’ve learned to cast Cure Light Wounds and magic-users/illusionists can do the same to cast Read/Detect Magic. Druids don’t get this very sensible bonus – but they do start with 2 spell slots at first level, so I suppose they’re OK. Fighters get a ‘cleave’ power that gets them extra attacks whenever they kill an enemy in combat – an innovation that certainly adds momentum to combat. Thief powers strike me as enhanced: Move Silently 33% and Hide in Shadows 25%, compared to 23%/13% in Labyrinth Lord, and a ‘why-even-bother-trying?’ 15%/10% in AD&D back in the day. One alteration set me thinking. Dragonslayer’s clerics turn undead on a d20 (like AD&D) but can only attempt turning three times in a day. Pick your battles, right? I can see the rationale for this. Lots of scenarios won’t feature undead at all, or just occasional instances (wandering monsters, a dungeon room that’s a crypt), so often this restriction won’t matter. But if you’re running an undead-themed dungeon – like, er, Barrowmaze – then clerical turning becomes the boring default for every encounter. This forces PC clerics to weigh up whether undead can be dealt with by violence and use turning only after careful deliberation. Turn, Undead, Turn by CaptainNinja on DeviantArt There are two unexpected classes. Monks appear, but radically redesigned. These are not the Kung Fu martial artists of AD&D; no, they are very much medieval-style mendicants, more Friar Tuck than Grasshopper. One of these Monks is not like the other one! They even start off knowing ‘Ancient Common’ (which, I guess, means Latin). They don’t wear armour but their AC improves every level. They get combat feats with a quarter staff. They can chant. At higher levels, they get clerical spells and turning undead but also do Comprehend Languages at will. They feel a bit one-note to me, but at least they’re coherent. Barbarians are back, but these are the ‘Asbury Barbarians’ (referring to Brian Asbury’s prototype for the class published in White Dwarf long ago and discussed here). They are limited to light armour, fly into berserk rages, and get a few thief abilities, but they scorn magic. It’s a classic build and this seems to be a coherent iteration of it. The Main Course: spells, monsters, magic items - and a few rulesI won’t dwell on the spell lists. They seem to be the AD&D-via-Labyrinth Lord canon, with some renaming to throw the lawyers off the scent. The descriptions are even more concise than Labyrinth Lord, but I wish there were page references for them – or an index!!! – and this complaint recurs with the monsters and magic items. The monster bestiary is extensive. Dragons get good treatment (complete with a multi-headed ‘Mother of Dragons’ – ahem) and the coverage of Demons’n’Devils is refreshingly candid. I guess you can’t copyright Mephistopheles, but I’m surprised to find ‘vrock’ appearing as the lowest order of demonkind – these infernal naming conventions have been imported wholesale from the AD&D Monster Manual rather than reinterpreted. Presumably Dr Gillespie took good advice on that – or perhaps he figures that family-friendly Wizards aren’t going to get involved in a legal spat over legal ownership of demons!!! Oh, and the picture of a Hobgoblin on p170 is a delightful homage to David Sutherland’s iconic ‘samurai’ style for them. The magic items list is particularly good – unsurprising, since Gillespie shows himself to be a prolific inventor of magical gewgaws in Barrowmaze. Intelligent swords get a careful treatment, Dhurinium (mithril) armour is linked to the imagined setting in exciting ways, and there are lovely tables for randomly generating hordes – again, no surprise if you’ve seen Barrowmaze. What does come as a surprise is just how short the main rules section is: a couple of pages covers combat, dungeon exploration, and saving throws. This is testimony to how well-designed earlier sections were, drawing together the key information into the treatises on character classes and abilities, so it doesn’t need to be repeated here. You need a 20 to hit AC 0, and you get modifiers to make that easier as you go up in levels, rather than having complicated tables for each and every class. Strangely, the same minimalist approach is not adopted for saving throws. Missed opportunity there, I think. One effect of this is to de-power monsters, who also hit AC 0 on a 20 and follow the same bonuses as fighters, which means +1 to hit at 3HD and with every HD thereafter. This means 2HD monsters are no better than starting characters, which is bad news if you’re a Gnoll. The Dessert: good adviceThe last 30 pages offer some fantastic resources, such as advice on dungeon design, wilderness campaigns, excellent random tables to map and stock dungeons, and a cute time tracker with rest breaks and wandering monster checks included. So, Should You Buy It?Recommending Dragonslayer is complicated – it depends on what you’re looking for. If you collect OSR retroclones, then you’ll want to add this handsome book to your collection. If you are intending to play a retroclone RPG and you wonder if Dragonslayer might be the best purchase, then there are things to consider. Dragonslayer is quirky. It’s full of departures, great and small, from the pristine D&D rule set of yore. I’m not just referring to the regrettable Cyclopspersons or the way the game hybridises elements of Basic D&D with the classes and spells of AD&D. There are all sorts of ways in which Dragonslayer differs from the game that people were playing in 1978. Thieves actually have a decent chance of doing something useful at 1st level, for instance. But if you want to dust off some classic modules, like say, B2: The Keep on the Borderlands or G1: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, then perhaps you want that authentic early D&D experience without the innovations. May I direct you instead to Blueholme for B2 or OSRIC for G1. Or Advanced Labyrinth Lord if you want the hybrid rules without the novelties. It's only fair to add that you can pick up these earlier retroclones (with their royalty-free art and functional layouts) far cheaper. If you’re not looking for the authenticity, but you are shopping for an OSR rules set with a contemporary flourish, then Dragonslayer is a strong contender. However, there will be a post-OGL revised edition of Labyrinth Lord later this year, which author Dan Proctor promises will also break with the D&D mould in exciting ways; it looks rather beautiful and also has a cyclops PC race, if that’s a weird deal-breaker for you. Hexed Press previews Labyrinth Lord 2e The third consideration is whether you use Greg Gillespie’s excellent megadungeons. If you are playing Barrowmaze, for example, then Dragonslayer fits it like a glove. Indeed, several features of Dragonslayer seem to have emerged specifically in response to the design decisions in those dungeons (like the reconsideration of clerical turning). If you want to get into those big, daunting, exciting dungeoneering projects, then Dragonslayer is a no-brainer. Get on board. For me, the charm of Dragonslayer is its 'lived in' feel. Despite the speed with which it was brought to press, it doesn't feel rushed. You very much sense that this is the consummation of Greg Gillespie's own D&D campaign, with house rules and good practice developed over many years. Everything feels lovingly crafted and bedded in through recurring use. Despite being a new game, it feels like an old one, and that's praise that goes to the heart of what makes a retroclone appealing.

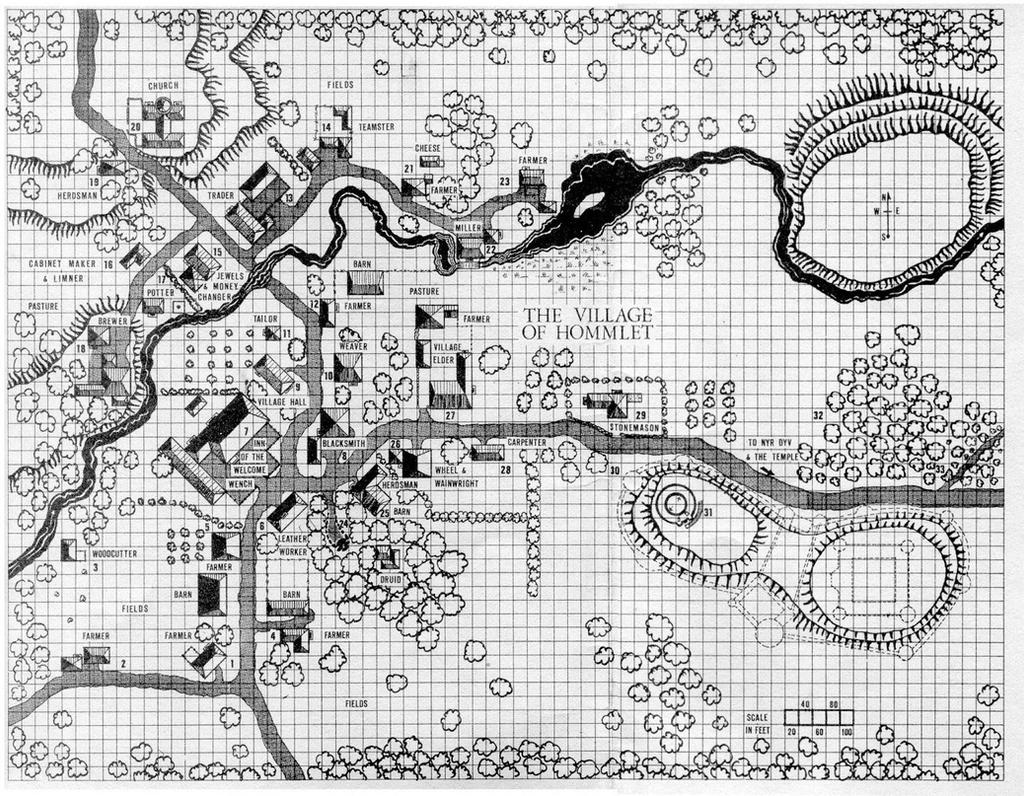

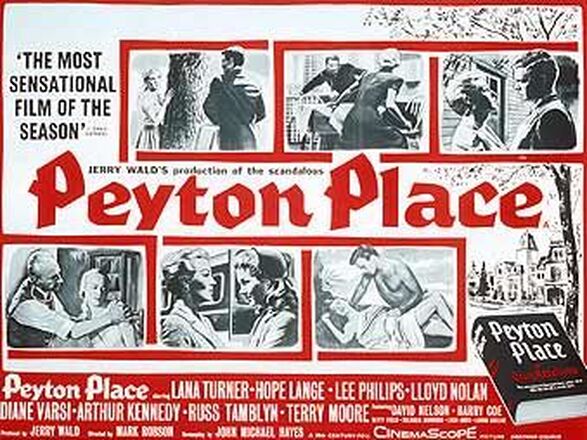

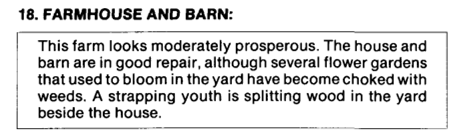

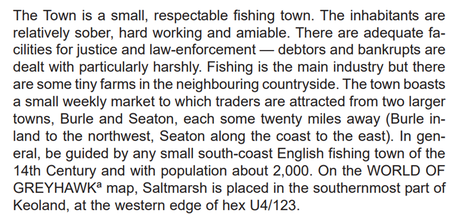

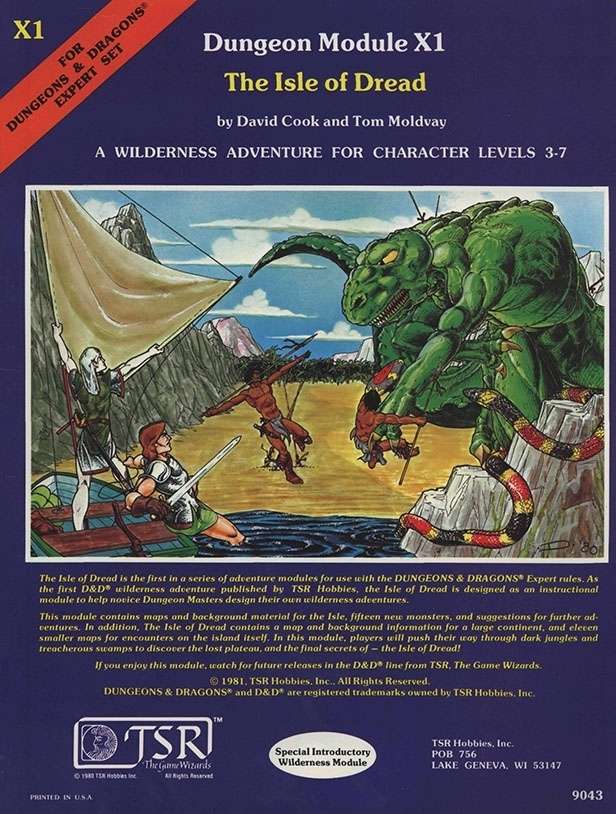

SPOILERS AHEAD: Fen Orc and Swamp Goblin dissect the classic 1982 AD&D module 'Against the Cult of the Reptile God.' My good friend Swamp Goblin and I have decided to put out a series of video reviews focusing on the RPG products that inspired us. Here's our first; my video production skills are pretty basic, but they're only going to get better. AD&D module N1: Against the Cult of the Reptile God came out in 1982. It was written by Douglas Niles, a former English teacher who bashed this out in 4 weeks: it was his first assignment as a designer for TSR. Niles went on to design other RPGs, like Star Frontiers: Knight Hawks and Top Secret: SI, had a big hand in creating Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms and authored a ton of novels. Reptile God is fondly remembered - and deservedly so - and a particular delight is the way it subverts the expectations of 'Golden Age' or Gygaxian D&D. In the early template, the village acts as a base for the PCs to raid a nearby dungeon. This gets its definitive outing in 1979's T1: The Village of Hommlet. Sure, there are dramas in Hommlet: you can go around gathering clues, you can recruit NPCs to your party, there are a pair of evil dudes who will spy on you for the nearby Temple of Elemental Evil, there are sectarian tensions between Druidists and Cuthbertites. But Hommlet is fundamentally static and benign and it's up to the PCs to make things happen there - or not, as they choose. You can see the influence of Hommlet on Niles' design of Orlane. There are rectangular houses on neat patches connected by public roads and screened by attractive trees. It looks like no medieval town ever; rather, it's a sort of idealised American frontier settlement, somewhere north of Walton Mountain and south of Avonlea, not far from St Petersburg, Missouri. This sort of American idyll, passed off as pseudo-medieval Europe, is very common in fantasy RPGs. You can see it in Greg Stafford's Apple Lane (1978, one of the first RuneQuest scenarios) and I do a deep dive on Mark Kibbe's World of Juravia over here. I mention in the video that an interest in what lies beneath the surface of small town American life has a long pedigree in American literature. I forgot to mention the link cited by Stephen King himself: Grace Metalious' 1956 novel Peyton Place which explores lust, incest and murder in a sleepy New England town. It's the close resemblance of Homlett and Orlane to idealised American communities - rather than actual medieval ones - which drives home the themes of corruption and secret conspiracy so effectively. Niles builds on Gygax's wholesome template in several ways. For a start, he's a better writer and each location is introduced with snappy read-aloud captions that establish more than the size and shape of the property. Attentive players will pick up on tell-tale details of chaos and neglect that indicate (often, but not always) the influence of the Reptile Cult. Niles takes the implied drama of Hommlet and makes his setting fully dynamic. Over a period of days, the Cult will abduct and brainwash the free-willed villagers, in a particular order. This is a community that changes while the PCs are here and if they do nothing at all they will still notice events going on. Niles is sometimes credited with introducing a more investigative, less combat-orientated approach to D&D. Sandy Peterson's Call of Cthulhu RPG came out the previous year (1981) and it's hard not to see the thematic links here - although Niles would have had his work cut out to read and digest Call of Cthulhu and then bash out this Cthulhu-esque module in the time available, so it is perhaps a coincidence. Another possible coincidence is that 1981 saw the release of the first British AD&D module, U1: The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh, by Dave J. Browne with Don Turnbull. Saltmarsh surely beats Reptile God to the punch when it comes to delivering an investigative AD&D adventure. I'm not sure whether Niles would have been aware of the material being created by TSR (UK) and - again - the time frame doesn't leave much scope for a direct influence. But in any event, Niles' Orlane differs from Saltmarsh in fundamental ways. For a start, Saltmarsh isn't mapped or detailed: it gets a pretty lightweight description: Interesting: the World of Greyhawk location puts Saltmarsh south of Orlane, in the neighbouring Kingdom of Keoland. OK, it's a few hundred miles away, but the same general region. Moreover, the whole point of Module U1 is [SPOILERS] that, despite all appearances, there isn't actually anything supernatural going on - whereas in Orlane, despite the superficial prosperity, there is an occult menace at work. U1: Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh is not an adventure I've ever loved. It feels anticlimactic to me, far too invested in atmosphere and not enough drama and, despite all the investigation and clue-finding, it ends up with a massive fight that can easily overwhelm a low-level PC party (the NPC magic-user has a Sleep spell, ferchrissakes). The secret is not particularly sinister - or even particularly secretive. One thing you cannot accuse Saltmarsh of, though, is being too American. It's all fog, brine, fishy smells and a general sense of murkiness. The later scenarios in the U-series bring in reptile-people (Lizard Men, Sahuagin) and their cults, but there's a complex and realistic political situation unfolding: they're not just 'monsters.' Meanwhile, N1: Against the Cult of the Reptile God picked up critical plaudits, but never spawned a sequel. The N-series turned out to be N-for-Novice: a string of modules supposedly designed for starting characters, not a series developing the region of Orlane, the Rushmoors and the fallout from the destruction of the Cult. The next N-module came along in 1984 and Carl Smith's N2: The Forest Oracle is (not entirely unfairly) pilloried as the worst TSR module ever. In particular, it's condemned for its sloppy and ineffective writing - which only throws Douglas Niles' strengths as a designer into sharper relief. In the video review, Swamp Goblin and I discuss different ways that N1 could develop after the destruction of the Cult. Maybe Module alt-N2: Revenge of the Goddess Merikka, is something I'll have to write myself ... In the meantime, our next deep dive review will be the oh-so-problematic Module X1: The Isle of Dread.

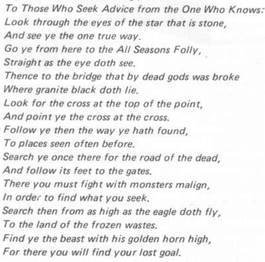

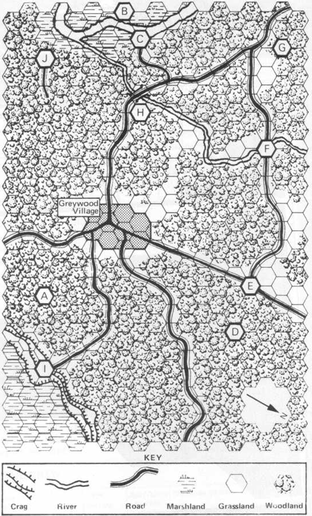

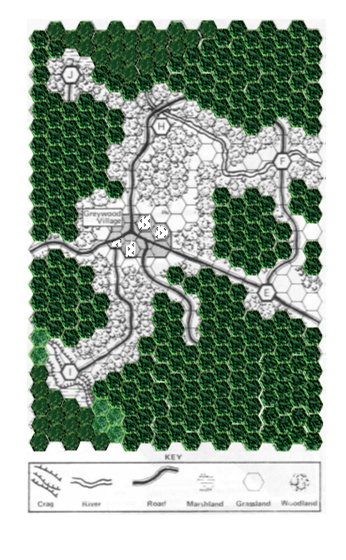

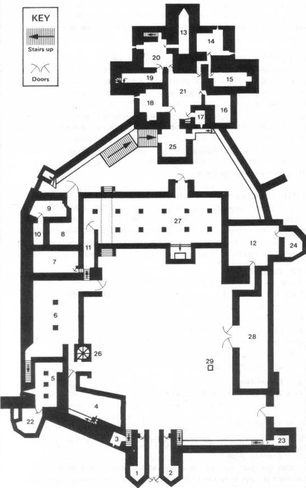

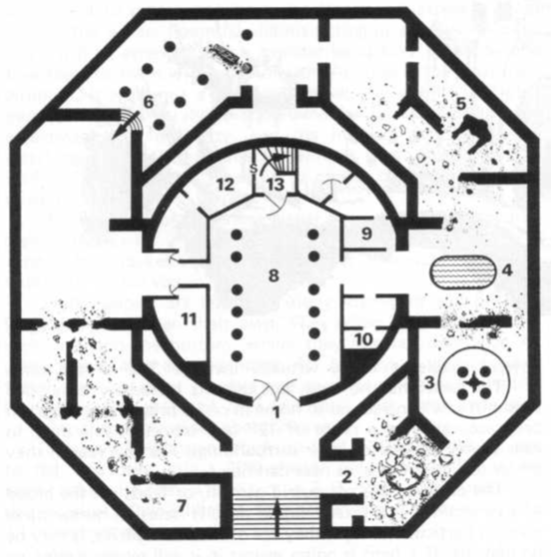

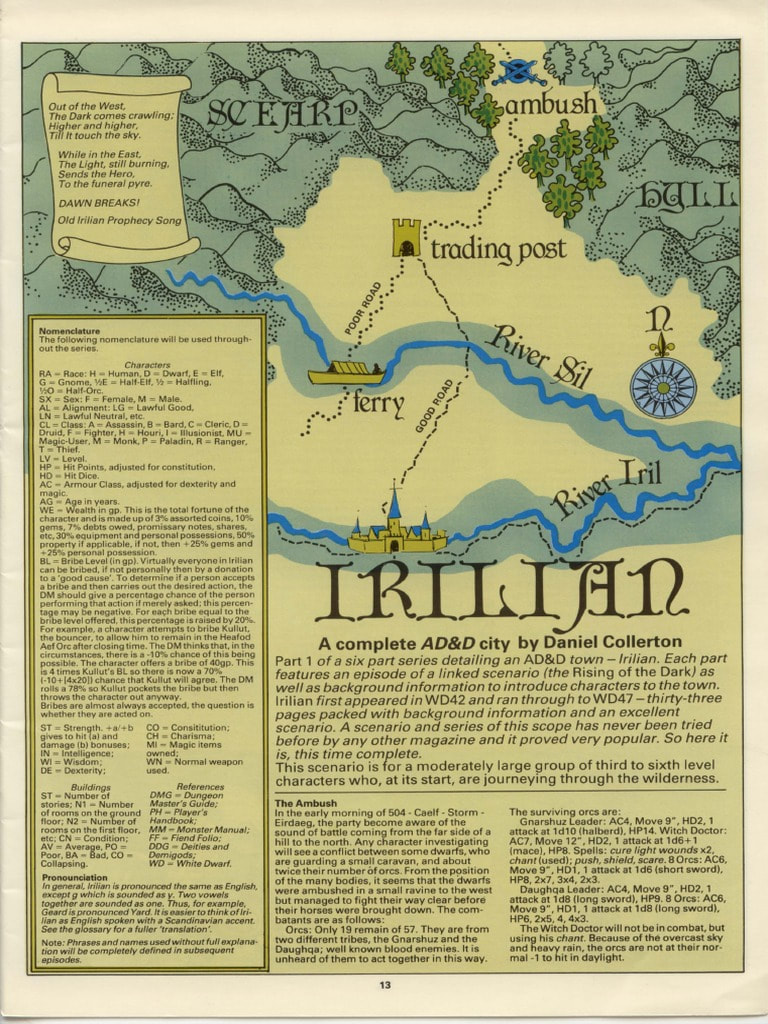

Like a lot of people, I like to celebrate my birthday by getting friends together for a game: either one of those big brainy wargames like Dune where everyone ends up in the kitchen, plotting, or else a jolly, feel-good RPG session, a sort of festive one-shot. Covid Lockdown imposes constraints on both activities, but the wargame more than most. So we gathered this afternoon to play old school D&D: five players and myself, talking through Zoom, rolling dice on Hangouts and me showing maps and floorplans by sharing a PowerPoint display. But what adventure to run? I'm time-pressed, right ahead of returning to work tomorrow, so it has to be a pre-made module. Time to dust off one of those old classics from the glory days of White Dwarf magazine. My eye falls on Barney Sloane's The Search for the Temple of the Golden Spire from White Dwarf 22 (1980). You can also find this mini-module in Best of White Dwarf Scenarios II Barney's adventure had always been a favourite of mine, although I'd never run it. How would it stand up, after all these years? I think, back when I was 13, Golden Spire impressed me immensely. This was no underground maze or skirmish in a fortress. Barney set out an attractive wilderness map extending around the village of Greywood, complete with ruined towers, Cloud Giant lairs, talking trees and a forest full of gnomes and sprites. There are two mini-dungeons to encounter. There's a riddle that serves as a coded map to guide players from one end of the wilderness to the other, culminating in the eponymous Temple where some very hardy monsters reside. The whole thing has a folkloric, faerie atmosphere that appealed to me greatly (and still does), brewing up elements of Spenser's Faerie Queen with its forest in which big evil temples pop out of the landscape and queer woodland folk offer cryptic clues. Remember, this was only 1980. This sort of above-ground adventure in an atmospheric wilderness setting was quite novel. B2 (The Keep on the Borderlands) only appeared the previous year and the wilderness segment of that was only a prelude to the real business of clearing out the Caves of Chaos, one goblin at a time. Usually, wilderness was just something to cross in order to get to the adventure: here it was part of the adventure itself, along with a small town-based segment as well. Although Jean Well's B3 (Palace of the Silver Princess) contained a wilderness element and a similar faerie vibe, it was (in)famously recalled and rewritten; the next product I would find with this sort of integration of setting and adventure, Judges Guild's The Illhiedrin Book, was still a year away. If you're my age, your adolescence is defined by either these covers or The Clash's record sleeves. Rereading Barney's adventure, 40 years on, I can see some flaws. It occupies that strange twilight zone between Original D&D and AD&D: creatures from the AD&D Monster Manual are referenced, but this is a OD&D adventure through-and-through, with little or no reference to the Dungeon Master's Guide's rules for wilderness travel, for example. There are confusions and omissions. What's the scale of the map? How far can PCs travel? How often do you check for Wandering Monsters? More importantly: just why, exactly, are the PCs seeking the Temple of the Golden Spire? Nowhere does the scenario explain what it is or why anyone would want to go there. It's sort of assumed that, once a Celtic Cross expounds a riddling quest, adventurers will just rush off and risk their lives to fulfil it on general principle. Certain aspects of the riddle are unexplained and there seem to be crucial details missing from the description of Greywood: what is the star that is stone? what's the deal with the abandoned house? what exactly do the clerics know about the Temple? what's the deal with Greycrag Citadel, visible on the horizon? You get the impression that Barney didn't bother setting down on paper everything that was going on in his campaign setting. Nevertheless, this scenario inspired a host of imitators in the pages of White Dwarf who corrected his mistakes, even if they never quite capture the faerie charm of Golden Spire: Phil Masters' The Curse of the Wildland (#32 and exemplary, like most of Phil's stuff) and Paul Vernon's Troubles At Embertrees (#34) were both from 1982; Stuart Hunter's The Fear of Leefield (WD#60) from 1984 and Richard Andrew's prize-winning Plague from the Past (WD#69) from 1985; all did a fantastic job of sending the PCs from a village in peril, through a cleverly constructed wilderness setting to a micro-dungeon showdown, but with a tighter plot and closer attention to AD&D rules. The thrill I used to get as a schoolkid when these things came thumping through the letter box.... It's not a problem filling in the gaps in Barney's scenario. He seems to intend some clue in the stone cross to send the PCs journeying down the road to the east. I introduced an evil presence in dreams that was recruiting villagers to the cult of the Golden Spire and the disappearing peasants act as impetus to investigate and the PCs' own nightmares make the stakes personal: if they cannot locate the evil temple and destroy its power, they too will convert to Chaos. AD&D, OD&D or ... gasp .... Holmes ???1980 was an odd time for D&D. The AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide had just been published - I acquired mine for Christmas in 1979 so it's quite possible Barney Sloane didn't even own it when he composed Golden Spire, perhaps using only the AD&D Monster Manual and the Original D&D rules set for his campaign. That would explain the odd, eldritch tone of his adventure. Back in 2020 I ran a campaign using the wonderful White Box rules, which do a great job of capturing OD&D. In fact, there's a huge section of this website documenting my attempts to reverse-engineer lots of character classes into White Box's delightful 10-level world. I promised myself I'd next turn to Blueholme next to capture the flavour of the Holmes Basic Set. But for this scenario, I wanted to try something different: the Blue Hack RPG. Three brilliant OSR rules sets - click on the images for links to purchase: PDFs of White Box and Blueholme are pay-what-you-want and Blue Hack is under £2 Blueholme and Blue Hack are both by Michael Thomas of Dreamscape Design. Blueholme is a straight-up retroclone of the Holmes Basic D&D Set, but the recent Journeymanne Rules expand the game to 20th level, introducing all sorts of PC race options beyond the basic Elves, Dwarves and Halflings along with lovely OSR art. Blue Hack is a different proposition. In just 22 pages, it condenses the D&D experience in the same style as the groundbreaking Black Hack RPG. You roll your classic 6 abilities on 3d6: Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Wisdom, Intelligence and Charisma. No modifiers or saving throws; if you want to hit something, you roll under your Strength on a d20; dodge an arrow, roll under your Dexterity; spot a secret door, roll under your Wisdom. Your class offers you Hit Points and damage is based on your class, not your weapon. Going up a level grants you opportunities to increase your abilities (try to roll equal to or over them on a d20). Monsters with more Hit Dice than you impose a penalty to hit or dodge them. Armour soaks damage. Every spell gets a single line of description; same with every monster. That's it. The rest is up to you. Blue Hack offers a few Holmesian tweaks to the Black Hack formula, like racial bonuses for the obligatory Dwarves, Elves and Halflings; some Holmesian spells and monsters; some refocusing of character classes. Enough to make it feel like 'Blue Book' era 1970s D&D. The beauty of this is the sheer speed with which you get a character up and running. You might think it's fast creating a character for Basic D&D, but there are hardly any tables to consult in Blue Hack. If you're creating characters online, over Zoom, this sort of pick-up-and-play ethos is invaluable. Blue Hack also suggests that PCs gain a level after every session/adventure/encounter - whenever the DM likes, really. With Golden Spire I wanted the PCs to start at 1HD (1st level) and rise to 3HD (3rd level) by the time they entered the Spire itself. This proved very straightforward - at various points, players got to roll and add those extra Hit Points, check to see if any abilities increased and expand their spell slots. Beautifully simple. So, what happened? [SPOILERS]Character generation throws up the usual adventuring misfits. David is a cretinous dwarven halberdier named Dimples; Emily an elven thief named Gnashe; Alex an elven fighter-mage named Azure-Wall; Oliver a good-looking human fighter named Gomez; and Karl turns to the macabre with a child cleric named Bilge who worships the god of scarecrows and communicates through a sock puppet.. This bunch don't ask for motivation: they study the riddle and get on with the quest. The tone is larky and riddled with Monty Python-isms: the villagers export walnuts and take everything literally, arm-wrestling resolves most interactions, cultists complain about itchy robes, no one believes gnomes exist. Not wanting to waste Barney Sloane's excellent scenario map, I moved it into PowerPoint for screen-sharing and covered the hexes with terrain-themed shapes, then deleted each shape as the party moved through the wilderness, revealing the map below. This was such an effective way of revealing a map and dramatising exploration, I'd love to do it for a round-the-table game, if such a format ever resumes. Yeah, you can probably do something similar on RollD20 ... The party discover Greycrag Citadel, infested with kobolds. It's a lovely castle map that I'll definitely re-purpose for future games. In this case, Gnashe sneaked in alone, found the viewpoint from the tower from which the Golden Spire could be located and the party covered her embattled retreat, chopping down kobolds and ghouls. Greycrag and the Temple of the Golden Spire: aren't those lovely? White Dwarf always excelled at scenario maps Heading to the Spire, the party have fun with wandering monsters: Yorkshire Centaurs and an Ogre teaching his son how to devour humans (feet first, of course). By the time they reach the evil temple, everyone is 3HD/3rd level and pimped enough to take on hard monsters, like a Harpy and the climactic Wraith (who of course drains several people of their levels before being pelted to death with the harpy's trove of silver coins). I decided that the introductory riddle was in fact sent by the Wraith, to lure the party to the Golden Spire and trick them into freeing him from his prison. It's a feature of Barney Sloane's old school scenario construction that, in his version, there's no explanation given for the presence of various monsters in the Temple of the Golden Spire: they're not doing anything, they're just waiting for adventurers to turn up and attack them. However, to his credit, Barney's kobolds in Greycrag Citadel are a fairly dynamic bunch, busy getting on with all sorts of interesting things when the PCs turn up: roistering in the big hall, torturing prisoners, sleeping on guard duty. That's another example of this scenario from 1980 being a sort of half-way house between the aesthetics of Original and Advanced D&D. Later, more sophisticated scenarios in White Dwarf in the '80s, by people like Phil Masters, would give careful thought to the presence of every monster and use them all in the service of an overall plot or theme. Overall, can Blue Hack really hack it?Blue Hack was a big success for this sort of level-up-as-you-go scenario. I'd love to use it for some of the old TSR Modules: Tomb of Horrors, maybe? or White Plume Mountain? Or dust off some later, more complex White Dwarf adventures, like Daniel Collerton's fabled Irilian city/campaign (WD#42-47). I'm not sure Blue Hack would serve for a conventional campaign. The roll-against-your-abilities system means that characters with high Strength or Dexterity will rarely miss - or get hit - in combat, even against tougher monsters. For example, with Strength 17, Dimples the Dwarf was hitting monsters with the same HD as him 80% of the time. How many 1st level characters in ordinary D&D have those odds? Without Armour Class, monsters enjoy some protection from damage, but a party of PCs can pile on the damage quickly, ending fights in just a round or two. Now, I quite like that - nothing is more boring than one of those OSR D&D fights that just goes on and on - but a sense of peril is lacking, especially as being reduced to 0 HP only has a 1-in-6 chance of killing you assuming the rest of the party survive to rescue you. The other feature is that, without experience points being needed to level up, PCs have no motives to seek out treasure. You might feel that's a good thing too: let adventurers be motivated by more realistic concerns, like duty or honour or saving the realm or rescuing loved ones. But it's surprising the amount of D&D material that's predicated on treasure as a motivator and if the PCs don't need to acquire it, all sorts of scenarios, traps, dilemmas and rewards need to be re-thought. Of course, you could easily paste a basic XP system onto Blue Hack to restore that mercenary motive. I think Blue Hack will be my system-of-choice for D&D one-shots, especially re-vamping old scenarios. It fast set-up and rather abstracted combat system makes it ideal for online RPGing. I like the fast fights and the option to assign level-ups at dramatic moments, rather than tracking XP. Its lack of 'grit' or peril might be a drawback, but it offers a fresh perspective on those old-school modules and scenarios. Did somebody say C2: Ghost Tower of Inverness? Let's go get that Soul Gem!

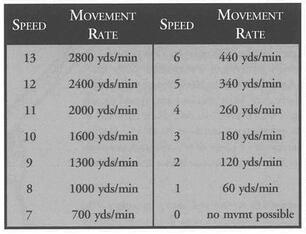

One of the distinctions that divides fans of different editions of D&D is the question, 'How long is a melee round?' Some lexical detective work is needed to figure out what D&D originally intended. Back in 1974, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson explain (in the Underworld & Wilderness Adventures expansion) that a 'turn' is ten minutes and there are 10 1-minute melee rounds in a turn. Gygax retained the 1-minute melee round for 1st and 2nd edition AD&D, justifying it like this: The 1 minute melee round assumes much activity – rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on. Once during this period each combatant has the opportunity to get a real blow in (1st ed. AD&D Players Hand Book, p39) The 1-minute round seems to have its roots in the wargaming superstructure that D&D emerged from. One minute allows a squad or battalion to move, line up, fire, generally 'take their turn'. Combat in wargaming is typically all-or-nothing, so in that 1-minute of action you might completely eliminate your opponent. Adapting this to tabletop RPGs produces a high level of abstraction. You're free to imagine a lot of cinematic business going on surrounding your solitary 'to hit' roll or spell. But it leads to absurdities. An armoured warrior can only manage short bursts of energetic combat, but combat in D&D can easily last 10+ melee rounds, especially in a 'cleric fight' (a fight between well-armoured characters with low damage output). That's 10+ minutes of huffing and puffing in quilted doublets, thick leather jerkins, mail hauberks... Impossible. While Gygax was working in minutes, Eric Holmes was tasked with presenting Basic D&D (1977) and unilaterally decided that the time frame for combat should be in seconds rather than minutes: Each turn is ten minutes except during combat where there are ten melee rounds per turn, each round lasting ten seconds (Basic D&D Blue Book, p9) Now that ten round fight lasts just under two minutes: much more realistic. Subsequent editions of Basic D&D - the 1981 beautiful edition by Tom Moldvay and the 1983 ugly edition by Frank Mentzer - retain this 10-second melee round. Moreover, Basic D&D charted the path that other RPGs followed. For example, Runequest defines fantasy roleplaying for non-D&D folk and hit upon a 12-second melee round. The melee round is 12 seconds long. One complete round of attacks, parries, spells, and movement happens during ascenario. (Runequest 2nd ed, p14) 12 seconds is long enough for it to eat your shield Then, in the 21st century, 3rd edition D&D switches to the 6-second melee round, which has been the standard ever since. Take that, Gygax. Holmes is vindicated! A round represents about 6 seconds in the game world. During a round, each participant takes a turn (5th ed. D&D Players Hand Book, p189) There are arguments to make both for the combat round as minute or handful of seconds. The 1-minute-round moves combat towards 'theatre of the mind' with a lot of improvised 'business' going on around the decisive blows. Tasks like picking up weapons, unsheathing swords, notching arrows, drinking potions and finding spell components are easy to fit into this stream of activity and don't penalise the character. But if you find such protracted combat unlikely, the 6/10-second-round offers a more moment-by-moment approach that suits tactical combat better, where facing and flanking matters; where you forfeit your action if you're caught unawares, if you have to ready your weapon; where it matters where you are standing and who you can see and whether you can reach somebody in time to hit them. But is it really likely that an armoured warrior can hit someone 6-10 times in a minute - or even twice that if they are high-level? Can archers really fire 12-20 arrows a minute, minute after minute? Can you really cast 6-10 spells in a minute, with combat going on all around you? The fast melee round seems to credit PCs with incredible vigour. Real Life Comparisons A medieval longbowman at the Battle of Crecy (1346) was expected to fire 12 shots a minute. That involves drawing and firing a longbow, which most people would find pretty punishing to do just the once. On the other hand, it didn't involve much aiming: longbows work because they drop a swarm of yard-long steel skewers onto the enemy, willy-nilly. And of course, this could not be sustained for more than a few minutes. A shortbow might be fired 20-30 times a minute, but, again, no one could sustain this. All of which favours the 10-second melee round more than the 6-second one, which allows a bow to be fired up to a dozen times. Moreover, how many arrows actually get fired in a 1-minute round? If the round assumes lots of 'shots' which only pin the opponent down or harry them, but include a couple of 'true' or 'effective' shots that have "the opportunity to get a real blow in", it's reasonable to assume an archer fires at least half a dozen arrows per minute, probably twice that. An archer with a quiver of 20 arrows will have fired all of the after a couple of 1-minute melee rounds. Jogging speeds in minutes and seconds Usain Bolt's world record is to run 100m in 9.58 seconds. That's about 200ft in 6 seconds or 330ft in 10 seconds. The average jogger covers 70ft in 6 seconds or 120ft in 10 seconds or a whopping 730ft in a minute. Now if we halve that 'jogging speed' for someone running in heavy clothing, carrying adventuring gear, in a darkly lit tunnel, over uneven and slippery floor, you probably get 35ft in a 6-second melee round or 60ft in a 10-second round and let's say 360ft in a minute. But it's even worse in heavy armour, carrying a sword, trying not to get killed. Even if we assume adventurers are trained to run around in armour, 35/60/360ft per round has to be the maximum and a more likely distance is 20ft in 6 seconds or 30ft in 10 seconds and 180ft in a minute, which is walking speed. 1st Edition AD&D (PHB p102) allows unarmoured characters to travel 120ft in a 1-minute round, which suggests a very cautious sort of walk. Halve that for characters in metal armour, which is a weary shuffle. D&D 5th edition has an unencumbered human traveling 60ft in a 6-second round, which is rather speedy, more like an actual jog along a smooth pavement. Basic D&D (Molvay or Mentzer) has unencumbered characters jogging 40ft in a 10-second round and lumbering 20ft in metal armour, which is comparable to AD&D speeds. Holmes Basic D&D allows 20ft movement in a melee round, 10ft if armoured, which is almost immobile by comparison. One of the less-remarked aspects of the development of D&D through the editions is how much faster everyone is now. A combat minute in Forge Out Of Chaos Indie RPG Forge confesses its derivation from D&D (especially 1st edition AD&D) in myriad ways, but its adoption of the 1-minute melee round is one of the clearest. After all, who would come up with such a profoundly un-intuitive gaming convention on their own? But Forge imports some ideas from other RPGs that sit uneasily with the abstract 'melee minute'. For example: armour. D&D treats armour as an impediment to hitting which works fine in a melee minute, where it's assumed your opponent takes lots of swipes against you and armour merely shifts the odds of being hurt in your favour. In 1978, Runequest took another direction, with armour deducting from dealt damage, which works well with its more simulationist 12-second round, in which combatants deal each other single bone-crunching blows. Forge tries to have it both ways. Armour makes you harder to hit (in an abstract, when-you-average-it-all-up sort of way) but also absorbs the damage dealt (in a specific that-blow-didn't-get-through sort of way). However, Forge usually inhabits the theatre-of-the-mind world of AD&D combat, where miniatures and battle maps are optional because positioning and facing barely matter. In Forge, you're either attacking an enemy's DV1 (including shield and Awareness bonus) or DV2 (no shield, no Awareness bonus) and there's nothing more specific than that. At least AD&D perversely factored in whether you were making a flank attack on someones shield-side or not (forgetting, temporarily, the rushes, retreats, feints, parries, checks, and so on of a melee-minute). But then Forge also forgets its melee-minute time frame when it obsesses about the range of magic spells and invites you to 'pump' spells to increase the range. Who cares what the range is when the spell is being cast in a busy minute in which you can dash over 100ft to get close to someone? Back in Holmes Basic, when a Magic-User might jog 20ft and an armoured Elf lumber 10ft, spell range mattered. Forge bases movement on the Speed (SPD) characteristic, determined for PCs using 1d4+1 (2-5). 'Yards' is an oddity: all the spell ranges are in feet. It's probably an unedited error and I'm always happy to enforce the convention that yards apply outside the dungeon but once you're underground, all yards count as feet. Forge also lacks any rules for encumbrance (but I offer house rules), so we have to assume these distances apply to unarmoured, unencumbered characters. If SPD 3 is the human norm, then adventurers are moving around much faster than in AD&D. If we apply AD&D logic, then characters in non-metal armour lurch about at 3/4 this speed and metal armour in 1/2 this speed. Nonetheless, if you've got SPD 5 then, even in plate mail, you will cover an impressive 170ft in a melee minute, much faster than AD&D. (I'm not even going to get into the whole conceptual muddle about whether SPD is supposed to represent reflexes or brute strength, the latter of which matters more for hauling yourself across a combat zone in armour.) If you can cover this sort of distance in a melee-minute, you don't worry too much about the range requirements of bows (which Forge also dispenses with) or spells. You just jog until you're close enough to your opponent and ZAP! Does anybody use melee-minutes any more? Gary Gygax ported the concept of the melee-minute into AD&D and Forge cloned it in an unreflective moment, but neither game really gets to grips with the implications. Gygax links his melee-minutes to another of D&D's defining concepts: Hit Points. What does it mean for a high level character to amass Hit Points sufficient to endure any number of sword blows? They haven't increased in literal physical toughness, but rather such areas as skill in combat and similar life-or-death situations, the "sixth sense" which warns the individual of some otherwise unforeseen events, sheer luck and the fantastic provisions of magical protections and/or divine protection (Dungeon Master's Guide, p82) In other words, some 'hits' in combat aren't even 'hits' at all. They're like the lost lives of a cat. The axe whistles through the space where your head was a moment ago, but some instinct made you duck. You lose Hit Points, representing pushing your luck, but you're physically unharmed. Yet, in another mood, Gygax is devoting pages in the Dungeon Master's Guide (e.g. pp52-3, 64, 69) to tactical movement, as if he were offering rules to a skirmish game with the action paced out in heartbeats, forgetting that all this is redundant in a rules set where, each minute, characters move great distances ("rushes, retreats") and the 'to hit' roll represents shaving away your opponent's luck rather than actually stabbing them. You can see why later editions of D&D followed Holmes down the heartbeat route of melee-moments rather than melee-minutes. Yet it leaves D&D with the preposterous institution of Hit Points, now bereft of its only justification, that a damaging 'hit' in combat doesn't necessarily involve any physical contact. If D&D can't square the circle of melee-time, then I can't 'fix' Forge's hybrid concoction either. In Forge, Hit Points are calculated from Stamina and don't balloon as you gain experience: a 'hit' in Forge is clearly something that leaves cuts and bruises. You use binding kits to regain your Hit Points, which you wouldn't do if all you'd lost was some good luck. In Forge, armour absorbs damage: if the armour deteriorates, then surely the axe did hit you! The long melee-minute loses its rationale. If I convert to the 'melee moment' approach - and I like the feel of Holmes' 10-second melee round - then all of Forge's spells last way too long and there's no point in 'pumping' them for extra duration (although extra range might become relevant again since unarmoured SPD 3 characters would only move 60ft per round or 30ft in plate mail). We can at least be consistent about the melee-minute approach. There doesn't seem to be anything to be done about the weirdness of two-handed swords which get swung once every two minutes. The convention comes from Holmes, with his snapshot 10-second rounds. Gygax did away with it in a moment of lucidity, but Forge ports it straight back in because it's really hard to make yourself remember that your melee rounds last an entire minute! Keeping track of arrows fired during a melee-minute seems irrational. In that space of time, an archer will fire almost all her arrows, then gather up the fallen ones to fire again. To represent depletion, just house rule that the archer's quiver goes down by 1d6 arrows every round, representing shafts that cannot be easily recovered. Then, at the end of the battle, the archer gathers them all back, minus a few lost or broken ones (perhaps, reducing the total stock by 1d6). In this sort of time frame, combatants can reach just about any area of the battlefield that their (rather large) movement allowance permits. Forge is onto something by treating tactical positioning as a simple DV1 (they saw you coming) vs DV2 (they didn't, or they're engaged in combat with somebody else). Place your miniature wherever you want to be on the battle map at the start of each melee minute. Or dispense with miniatures altogether! OSR dungeoncrawling without miniatures? I think I'd better think it out again...

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed