|

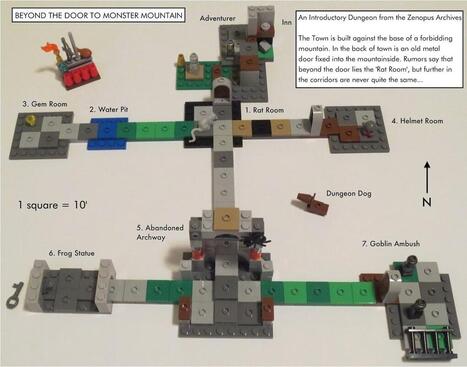

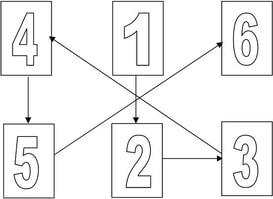

SPOILER WARNING: I'll be discussing this micro-dungeon in detail so AVOID if you want to play through it yourself. Zenopus Archives is a great site dedicated to 'Blue Book' or 'Holmesian' D&D - nothing to do with Sherlock but rather Eric Holmes who authored the first Basic D&D rules in 1977. Holmes' vision of D&D is lean and clean, retains a distinctive charm and is a pillar of the Old School Revival in Fantasy RPGs. It's also the first version of D&D I came across as a 11-year-old in the magical Christmas of 1978. Zenopus offers 'Beyond the Door to Monster Mountain' as an introductory dungeon: the sort of thing you could off to utter noobs or enthusiastic 11-year-olds who have just rolled up their very first D&D characters. It provided me with a nice exercise in Forge-conversion and it stands in its own right as a superb example of dungeon plotting through architecture. The map made out of Lego Heroica bricks is utterly charming too! You can read my adaptation to Forge Out Of Chaos on the Scenarios page. Beyond the Door to Monster Mountain, beside having a great title, is also a great example of the 'cross-stitching' design in which there's a fairly simple way through, with the rooms to be tackled in a set order, except that the players don't encounter the rooms in that order. This means they have to press on to the end then keep doubling back with the newly-acquired resources that exploit areas they have previously encountered. In this case, the dungeon layout resembles this After dispatching the rat in room 1, adventurers find the routes to 4 and 6 blocked (by a moat and a locked door) and are 'kettled' through to the spider in room 2. If they encounter the talking statue in room 5 it won't be able to help them without a big gem. The svarts in room 3 yield a ladder to cross the moat to 4, which yields a gem to feed the statue in 5, which reveals the key to 6, where a magical treasure awaits. The pleasure for the players comes in assembling an at-first meaningless design into a meaningful one: "Aha, so THAT'S how we cross the flooded pit!" Essential to the dramatic structure is that, architecturally, the players cannot encounter the resources they need sequentially, but if they persevere they will end up encountering them non-sequentially. They then acquire agency by arranging them in sequence. Agency is fun, especially because dungeons are disempowering environments, where you cannot go where you want to go and do not know what lies ahead. Once the dungeon design reveals itself, players no longer feel threatened by their environment: it becomes the agent of their purposes rather than themselves the agents of its structure. But this empowering sense of control has to be earned by first enduring passage through an environment that seems daunting and frustrating. This design philosophy was key to the old Fighting Fantasy books that Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone churned out in the 1980s. It underlies the original Multi User Dungeons (MUDs) in the '70s and their '80s descendants like Diablo and Nethack, where the detailed cross-stitching led to the user slogan "The Dev Team thinks of everything!" This sort of structure can be very satisfying but it depends on being satisfactorily concealed. In Monster Mountain, nothing makes sense until you reach the end of the dungeon and start doubling back. Larger dungeons can invite the adventurers to travel further and endure more before the pattern becomes visible. The problem with this structure is how controlling it is. The dungeon designer both sets the problem and solves it. The players are merely following the breadcrumbs left for them. If the dungeon is well-designed and atmospherically conveyed, the players will be excited by their own sense of agency in 'solving' the dungeon and not notice (or care) that they have only carried out a set of actions laid down for them in advance. But there's no option here for the characters to come up with their own solutions (jump the moat, break down the locked door) and, insofar as they manage to do this, they actually sabotage the narrative structure of the dungeon: it becomes meaningless if you encounter the talking frog idol after you've opened the door to the magical treasure room. The next dungeon I shall look at, The Golem-Master's Workshop by Tamás Kisbali, adopts a less controlling structure that allows the players to impose their own meaning on the encounters within the dungeon, making for a more open-ended scenario. One element of open-endedness in Monster Mountain is the Wandering Monster. Instead of the usual patrol of skeletons or goblinoid hoodlums, there is the Dungeon Dog. Shrewd Referees will make this creature seem menacing and unwise players will fight it, but it can be won over with food and recruited as an ally. There's something tragic about the poor dog living alone in the dungeon, fighting rats, and a resolution where he gets adopted by the adventurers brings a note of choice and sensitivity into a scenario that would otherwise be rigidly unresponsive. How does it play with Forge? Rats and Giant Spiders are monsters in Forge, with comparable deadliness to D&D. The spider venom does extra damage on a failed save rather than killing outright, which is a development I prefer. Ebryns (paralysing bats) seem to be a good substitute for stirges. Forge has no direct equivalent of goblins, no 'nemesis race' that players can fight and kill with a clean conscience. I could have converted these into a pair of Higmoni (who are basically orcs), but there are problems here. For one thing, they'd be quite tough, since they are player character peers. A pair of PC-level antagonists in armour can be a dangerous encounter for even 3 or 4 PCs who have just fought a rat and a giant spider. But more importantly, Higmoni are a PC race. In my session, the PCs were a Dunnar and a Human, but they could have included a Higmoni. What happens then? Why should they fight rather than talk. Let's settle this reasonably! There's nothing wrong with PCs resolving encounters peacefully - indeed, I'm in favour of it - but in this particular scenario there's nothing to negotiate over, nothing the PCs can offer the guards or the guards to offer the PCs. If the players have accessed the gem room, they don't need the ladder; if they haven't, they've got no loot to bribe the monsters. Instead, I went ransacking the White Dwarf archives and landed upon a 1978 contribution by Cricky Hitchcock, the Svarts, based on the goblinoid nasties from Alan Garner's The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960). In the AD&D Fiend Folio (1981), they mutate into Xvarts (for some reason) and it's under that name that they appear in Baldur's Gate. But I like the original name, which derives from the Svart-alfar (Black Elves or Swart Elves) from Norse mythology. Svats make sense in Forge as mutated Sprites, left over from the God-Wars, and with their Spritish Empathy devolved into a sensitivity to terror in their victims which makes them hard to fool or intimidate and grants them combat bonuses when they outnumber or pursue their opponents. With 6+1d6 HP, they're quite frail (compared to 15HP for a typical PC-peer opponent), so adding 1d6+4 AP armour and a 1d4 SP shield gives them only limited longevity. An extra +1AR from their tough hide gives them Armour Rating (AR) 3 but this will come down as their armour and shield get smashed up; nonetheless, it's enough to slow PCs down at the start of a fight. Attack Value (AV) 1 causes no threat to anyone, but it could rise to 2 if they gang up on a single foe or 3 if that foe tries to run away. The original dungeon design featured goblins armed with spears. Spears are a mediocre weapon in D&D, but a threatening one in Forge combat because, since they deal 2d4 damage, they inflict 2 actual damage with each hit. I decided to retain these weapons to give PCs a fright. However, when one Swart rolled a natural 20, the drawback of spears became clear: they break on the first notch, so after delivering damage to the PCs HP and AP, the monster was left unarmed. The original dungeon doesn't explain what the goblins are doing here. I improvised an extra detail: a chute in the corner descending to a deeper dungeon level. When the Svart lost his spear, he jumped down the chute and his beleaguered friend followed him. I advised the players not to bother pursuing. They had found the ladder, in any event, and were keen to double back to cross the moat they had discovered earlier. The dungeon leaves the players with about 150gp in loot. This is small fry in D&D, but it goes a long way in Forge. Starting characters usually cannot afford crucial spell components, armour repair kits, missile weapons and healing roots. After completing Monster Mountain, a pair of PC adventurers graduate into being well-armed and magically-enabled heroes, but they still need a lot more loot if they are to purchase all the components, armour and herbs they could wish for.

3 Comments

20/12/2019 01:42:17 pm

I just read this last night. Thank you for the review! Coincidentally, I was just thinking of revisiting this dungeon this holiday season. The rat room may have other unexplored exits...

Reply

Jonathan Rowe

20/12/2019 04:45:55 pm

I'll look forward to that. I'd love to see thus one expanded to a 2 or 3 tier dungeon that sends players further looking for that ladder !

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed