|

A Book of Ghosts by Jon Wright is a collection of eight modern ghost stories with an unusual framing device. The stories are presented as the unpublished manuscript of a once-successful writer who has composed these tales, claiming they are based on real life events. Between each story an email exchange unfolds between the writer and his agent, Joan Mailer, who isn’t impressed with this new direction in her client’s writing. At first, these emails seem like interruptions, but as the collection unfolds they take on an increasingly sinister significance A Book of Ghosts is available on Amazon as paperback and Kindle e-book The stories themselves are an imaginative set. All are rooted in British locales, especially small rural villages in Yorkshire, Scotland, Devon and elsewhere, although one is set in an unnamed Midlands city. The protagonists are the sceptical and diffident middle class types of the ghost story genre, unsure of how to process the supernatural within their rather staid but comfortable frame of reference. If a single theme runs through it is ‘Ambiguity’ because the stories often conclude abruptly, leaving events unexplained and contradictions unresolved.

There is one exception in the fifth story, ‘The Four Horseman,’ which features four working class friends and the failing football club they support. This is the one story with an entirely urban setting and in which the ghost is unambiguously present. This is the least satisfying of the set, perhaps because its rather light-hearted and sentimental treatment of ghosts is so at odd with the rest of the stories. The first tale ‘Will-O-The-Wisp’ is set on the wintry Yorkshire Moors where an American hiker finds herself led astray by the mysterious flickering lights. There’s a surprising time-jump in the narrative that sets the main storyline in a tragic but deeply mysterious perspective. The final situation can be interpreted in many ways: are the lights malevolent spirits or warnings? is the menace from supernatural forces or an all-too-human killer? The narrative drops this conundrum in the reader’s lap: I was reminded of John Fowles’ A Maggot’ (1985) which offers several possible ways of explaining the disappearance of a part crossing Exmoor in the 1730s, subverting each wild hypothesis in turn and proposing nothing certain. ‘The Drummer in the Band’ is the most conventional ghost story in the set and the one that comes closest to horror. The narrator looks back on the punk band he was in during his youth and reflects on the disappearance of their friend and drummer Noel. The band splits and the narrator moves into a conventional career but reconnects with Noel years later, apparently by chance, and listens to his old friend’s account of the night of terror he endured in the old Rectory where he was staying. The story of this night is simply spellbinding and the strongest piece of writing in the set. I’m reminded of H.G. Wells’ The Red Room (1894) in which the protagonist must spend the night in a haunted room and the encroaching darkness because a source of existential terror. This story captures that menace while leaving all other interpretations open: Noel was on drugs, was having a breakdown, was menaced by a spectre, was deranged by repressed grief. The denouement is no less ambiguous but chillingly effective. By far the scariest story in the collection. ‘The View Across The Sea Loch’ is a very different proposition. A young father buys a painting on a Hebridean holiday but in old age becomes fascinated with the increasingly eerie details that emerge from it. The description of the painting, its curious secrets and the sense of doomed narrative that develops inside its frame is really well-constructed. The narrator’s position – studying the painting in the toilet, during nocturnal visits to ease his prostate – grounds the story in a delightfully humdrum setting. What is finally revealed is spectrally imprecise yet starkly troubling. This story is a masterful exercise in slow-burning anxiety. ‘Back To School’ strives for a similar effect, though I think less successfully. A middle-aged widow holidays in a North Devon village where she is mistaken for a former pupil at the now-closed school. The batty old ex-teacher regales her with a sinister story, implying she murdered a young colleague. Subtle supernatural details intrude, but later the whole event seems to be imaginary, more like a vision or perhaps a strange case of possession. The narrative ends abruptly, but the lack of explanation here is not pregnant with possibilities, as it was with ‘Will-O-The-Wisp,’ but feels instead like the abandonment of a story that still had another twist or two left. ‘The Four Horseman’ comes next. Even though it is tonally at odds with everything else in the collection, it works well placed next to ‘Back To School’ because it delivers a clear and unambiguous ending. This is quite important because the next story, ‘The Old Path,’ repeats the formula of ‘Back To School’ and the effect is no more successful. Here, an arrogant social scientist turns his evening walk home into an experiment on fellow-walkers by creating a new path through a dense copse, to see if other people use it in response to behavioural cues. As the seasons turn to winter and the evenings darken, the narrator remains unaware of the growing menace in his journey. Finally, he finds himself pursued by a sinister force and trapped in a sea of mud. Again, the story ends abruptly: normal life is restored, without explanation or reflection, and the narrative feels aborted rather than resolved. No such criticisms apply to ‘Walking The Dog’ which vies with ‘The Drummer In The Band’ for star position in this collection, albeit for very different reasons. An elderly dog-walker encounters a stranger on his route. The narrator is a type made familiar by this collection: staid in habits, rather smug, inclined to read too much into things. Nothing of moment occurs on each meeting – the two men exchange banal pleasantries – yet on each occasion the sense of strain grows, eventually becoming outright menace. At the outset the narrator reveals that he believes the other man to be a ghost; only at the very end does anything justify this. The closing coda contains a startling detail that sends you back to the two men’s parting, trying to work out which was the ghost all along. ‘Walking The Dog’ would probably nudge ‘Drummer’ out of top position, except for its positioning right after ‘Old Path’ which it resembles too closely: both recount journeys along a rustic path as the season changes, both with a similarly supercilious narrator. ‘Walking The Dog’ is the better story by a mile, but its strengths are obscured by being placed alongside its weaker, but structurally similar, predecessor. After ‘Walking The Dog’ the final story, ‘Lansdowne Road,’ would have its work cut out for it. It’s a fine tale of premonition and the unfolding of fate over an imagined lifetime. It lacks the thematic punch of the earlier tales; although many scenes are sharply realised, it exists in the shadow of the preceding story. Most readers will come away misremembering ‘Walking The Dog’ as the climax of the set. Discussion of sequencing needs to consider the framing device of the author’s correspondence with literary agent Joan Mailer. At first, Mailer is the star of this exchange with an outrageously flamboyant turn of phrase, all easy bonhomie and complacent privilege. As the author’s mental state deteriorates, Mailer becomes concerned, then frightened. The final story, ‘The Brocken Spectre’ which was mentioned back in ‘Will-O-The-Wisp’ has been redacted from the collection and we are left instead with a vanished author and, perhaps, vanished Mailer too. It’s an artful device that moves the sense of dread out of the literary world and into the real world of author and publisher. I’m not sure whether the closing lines – a menacing expression from the Spectre itself, directed at the reader? – are really warranted. The author’s email account revealed as unavailable and unresponsive is as final a message from the grave as you could wish for. There’s a lot to enjoy in A Book Of Ghosts and Jon Wright’s steadfast commitment to ambiguity would warm M.R. James’ dusty heart. I’m not convinced that ‘The Four Horsemen’ really belongs in this set and there are a couple of stories that perhaps need a bit longer ‘in the oven’ so that satisfying resolutions can be found for them. I wonder at the decision to position ‘Lansdowne Road’ as the final tale. Yes, it features death, but the collection’s theme is more evident in ‘Walking The Dog’ and it is that story which makes explicit the device of narrator and ghost swapping places. I like using iTunes to re-sequence my music albums and I wish Kindle would let me move ‘Walking The Dog’ to the end, to round off the collection in a truly unsettling way. The only other improvement to A Book Of Ghosts would be a bit more effort on presentation: a contents page is a really important tool for finding your way around e-books and the story titles could do with standing out a bit more (larger typeface, emboldened, etc); it would be nice to get an author bio. The stark text simply drops you into the first email then rattles on to the end without a break, after which blank pages and silence. Yes, it fits thematically with what the text is aiming for, but it's a barrier to enjoying the book in other ways. There: I set out to write a few hundred words reviewing A Book Of Ghosts and I’ve done more than twice that: a clear testimony to the power of this collection of deeply thought-provoking ghost stories.

0 Comments

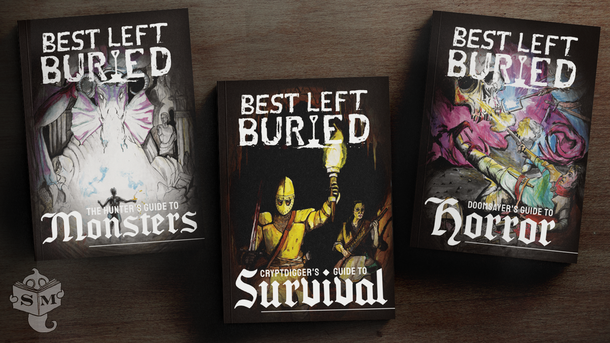

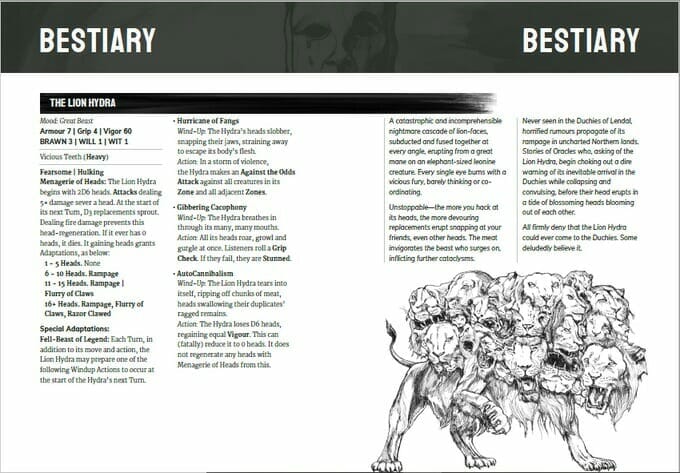

I'm not sure why I backed Best Left Buried on Kickstarter in 2020. I mean, I really like OSR roleplaying games, but I thought I'd found my sweet spot with White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game (for that old skool D&D itch) and The Black Hack (for everything else). What was I thinking, investing in some oddball dungeoncrawl game? After all, my own players had tired of dungeoncrawling, so who would I even use it with? Maybe it was the ominous title or maybe it was the faux-amateurish chiaroscuro art. Maybe it's the irresistible blend of sanity-shredding horror and underground skirmishing. Whatever: I pledged. Then I forgot about it until the rulebooks arrived this summer. Then I forgot about them for a good few months. But they teased me from the Shelf Of Shame where I'd consigned them. Yes, I think it was the art that made me start dipping into them. And I was hooked. So I GMed a game with a couple of players. And they loved it! Yeah. It's the art. Best Left Buried is produced by SoulMuppet Publishing, a friendly duo of Zach Cox (words) and Ben Brown (art), who describe it as "a fantasy horror game where the monsters are scary and the players are scared." In the format established by AD&D, there are three (slim) books in the rules set: The Cryptdigger's Guide to Survival (a Player's Handbook), The Doomsayer's Guide to Horror (a DM's Guide) and The Hunter's Guide to Monsters (a Monster Manual). Interior art is all black and white, but there's loads of it; the print is large and friendly to the eye, the paper is heavy and each book is about 100 pages. Physical copies seem to be sold out but the PDFs are from SoulMuppet or drivethrurpg (and the bundle is £10 at the time of writing) What you get is a very stripped back RPG. There are just three stats - Brawn, Will and Wits - and you assign +2, +1 and +0 to them. Tests involving rolling 9+ on 2d6, adding your stat bonus. In combat you roll 3d6 and choose two dice to pass the test and the third die is your damage. Damage is deducted from your Vigour (starting at 6 + Brawn) but a roll of 6 on a damage die usually imposes an Injury - roll on the Injury table; it could kill you outright. If your Vigour hits zero, down you go. Flip a coin. Heads you wake up later with an Injury, tails you die. Yeah: it's that sort of game. The rules advise you to create three characters so that replacements are at hand as they die off. Don't get too attached. Spawning a new character just became instantaneous with this cute character generator by David Schirduan The other important stat is Grip, which starts at 4 + Will. You spend Grip to get re-rolls or use magical powers. Awful events will force Will tests which, if failed, cause you to lose Grip. When Grip hits zero you go irrevocably mad, have a heat attack, turn to evil or leave play in some other disturbing way. Unlike Vigour, which is healed by rest, it's very difficult to regain Grip. Difficult, but not impossible. A player can choose to acquire an Injury or Affliction at some dramatic moment in play. Injuries reset your Grip to 5, Afflictions reset it to 10. Injuries might be temporary or minor (but could kill you outright); Afflictions are mental illnesses, mystical curses or spiritual corruptions that slowly turn your character into a basket-case or a monster: Debilitating Dread forces you to spend more Grip in triggering situations, Man-Eater means you can't heal through resting unless you've eaten human flesh. You get the idea? This simple little system leads to interesting choices. Do you keep resetting your Grip while your character disintegrates physically and mentally? Or do you stay pristine and avoid using or spending Grip at any cost? As your character gains experience, they get more powerful Advancements (of which, more in a moment) but go madder and badder and more decrepit. When a character dies, a fresh-faced recruit won't have all the crazy skills the old one accumulated, but won't have the burdensome problems either. Love the art. Characters can be built from 13 Archetypes. These are your familiar character classes but given a grimdark twist: Believers have a holy mission and Cabalists have numbed themselves with horror already; Freeblades are mercenary warriors but the Everyman is an ordinary fish-out-of-water; Dastards are city-slicker scoundrels and Scholars have forbidden knowledge. You also get a Journeyman Advancement with a cool name like My Shining Armour Gleams or Spirits of the Beyond (or, y'know, just take +1 Brawn or +3 Grip). Levelling up means earning 8 experience points and converting them into +1 to your Grip and Vigour plus a new Advancement. Four Advancement qualifies you for the Heroic Advancements (available in one of the PDF 'zinis' that detail all the stuff that was wisely left out of the core rules). How do you earn xp? Well, not from killing monsters. Monsters are to be avoided, fled or outwitted and only fought as a last resort. You get 1 xp from passing a Grip test. You also get xp from the treasure you drag out of the dungeon (sorry, from the crypt). There's a neat system for this too. Each adjective adds or subtracts 1 xp for a treasure: a golden goblet is worth 1 xp, a gleaming golden goblet is worth 2 xp and a set of gleaming golden goblets is worth 3 xp, but a dented golden goblet is worth nothing ('dented' subtracting 1 xp) while a cracked gleaming golden goblet is only worth 1 xp. That's it. There are rules tweaks for different weapon types. The Doomsayer's Guide has a 'toolbox' of house rules to choose from covering different approaches to healing, initiative, dying etc and those 'zinis' add even more. The rest is taken up with campaign settings, a complete dungeon (sorry, crypt) called Lord Edmund's Barrow and much sound advice for creating crypts (i.e. dungeons) and making the game scary. Then there are the monsters. OK, that's ... different The Hunter's Guide offers templates for the generic monsters of fantasy RPGs, but offers some evocative names (like Cinderbeasts for demons) but then goes on to provide a selection of detailed beasts that are quirky and memorable - like the Lion Hydra above. Monsters have a pretty simple stat block (Armour and Vigour and the three stats are all that usually matter) plus a bunch of Adaptations which are the monster equivalent of the players' Advancements. There are some very wise features here too. Monsters have Omens, which are the ways their appearance is foreshadowed (like bloodstains, claw marks on the walls, distant howls) - remember the point is not to fight these things? They have Moods that describe their behaviour. They might have a Wind-Up which occurs before they use their powers, tipping observant players off to what's coming. There are tables to generate everything randomly, if that's what you want. In fact, designing tables seems to be Zach Cox's delight. There are (optional but fun) tables to roll up your starting equipment, your weapons, your old profession, even your name. The emphasis is on hitting the ground running with a new character or monster and then bringing creativity to bear to explain what you've concocted. The final ingredient in Best Left Buried is your Company. Best not go there ... PCs are Cryptdiggers who belong to a Company that loots dungeons (I'm not going to call them crypts so stop trying to make me) as a business enterprise. Outside of the dungeon, the PCs have bosses, camp followers, quartermasters, healers, a complete military camp. You hand over your treasure in exchange for equipment and board. The GM and players are encouraged to develop this Company almost as a character in its own right and, naturally, there are quirky tables to help you do this. There seem to be two inspirations at work here. One is RPGs like Blades In The Dark that position all the PCs as part of a 'crew' of thieves and ruffians: the crew will outlast individual characters and the players might take responsibility for several different characters within the outfit, choosing which one to roleplay on any particular occasion. The other is Tyler Sigman's video game Darkest Dungeons which proposes that you manage a team of adventurers to explore the dungeons under a Gothic mansion, managing their unravelling sanity while you recruit new explorers to replace the ones who die, burn out, run away or murder each other. Best Left Buried encourages you to create vivid and flawed characters who will lead short, but horrifically memorable lives and continuity is ensured by the ongoing drama of the Company for which they all work. CritiqueI'm going to be clear up front: I really like this game. I like its simple but flexible rules engine, I like its dark and scrappy aesthetic, I like its RPG philosophy of frail and flawed heroes spending a lot of time running away, I like the corporate roleplaying involved in developing a Company and Camp, I like the left-field imagination at play in the monsters and naming conventions, I like all the silly tables. This means I can see why you might not like it. Maybe you like tactical combat. Maybe you don't like running away. Maybe you like characters to survive and prosper. Maybe you don't want your PC to die on a coin flip. Maybe you hate silly tables. Those are all fair and reasonable positions to take. They're just not my position. Actually, I do wonder about dying on a coin flip. To be fair, the Doomsayer's Guide offers alternatives to this. As part of my old White Box campaign I developed some pretty rigorous mechanics for keeping PCs alive while imposing wounds and frailties on them for surviving. I'm not sure players really appreciated it, in the long run. Best Left Buried takes a very different approach: view your PC as a transient figure, a "poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage" and reconcile yourself to sudden and unjust death. Continue the story of the Company with a new character. Take a wider view of your role in the evolving story. There are some flaws in the game and they are presentational, which is odd considering the role art and aesthetic plays in this game's appeal. There is no index. This is a big problem. If a monster has an Adaptation like Gelatinous Grip, is that in the Hunter's Guide or is it in the Cryptdigger's Survival Guide, because different monster powers are described in both? Where are Wind-Ups explained? Even though there aren't many rules, there are occasions where you want to look one up (or find one of those tables) and there's little help doing this. Adding to this problem is the way the rules are set out in the first place. There's a conversational approach that introduces concepts in the order that you need them while creating a character or designing a dungeon. That's great for the first read-through but it's terrible for using the rulebook as a reference tool, because weapon stats are in an early chapter (because you need to know about them while equipping your new PC) but combat rules are in a much later chapter. To make matters worse, when page references are given, some of them are wrong. For example, on p77 we learn that rolling a 6 for damage imposes an Injury and are referred to p39 for more on Injuries. Injuries are actually detailed on p87. When Chapters are referenced, they are referred to by number - but the chapters aren't numbered. It's all very well assuring me that a rule can be found in Chapter 6, but which chapter is chapter six? Giving powers quirky names is fine, but if you want to look up the power that lets a monster animate the dead and you've forgotten that it's called Corpse-mover you have to read through all the monster Adaptations until you find it. It's an unnecessary problem for what ought to be a pick-up-and-play game that looking something up 'in the moment' adds significant stress to the task of GMing. Of course, adhesive tags come to the rescue but not everyone wants their RPG books to become adorned with fluttering coloured pennants. House RulesA couple of rules don't seem to work as intended. Dealing an Injury to a monster is fiddly (off to p87 we go to roll on that table) and might kill an important enemy outright. Is that what we want? There's an Adaptation called Unstoppable that means a monster takes an extra d6 damage instead of an Injury - but that's actually worse than most Injuries. Would it be better to declare monsters immune to Injuries, even though that shortchanges players wielding heavy weapons? Or create a separate Injury table for monsters? Gaining 1xp for passing a Grip test strikes me as the wrong way round. Surely passing the test is its own reward and you should gain 1 xp for failing a Grip test. That would be more in line with the game's destroy-yourself-to-advance ethos. That art ... OverallA lot of love has been put into this game and it's a dark, demented and cruel love. There's a broad selection of scenarios for it and Zach kindly recommends a bunch of scenarios you can find online for free. I downloaded Skerples' Tomb of the Serpent King for my first game and that's a brilliant intro dungeon - so good, in fact, that it deserves a review of its own. OSR fans ought to take a look at Best Left Buried, especially if you can track down a print version. It's a shot in the arm for a dungeoncrawl genre that's rather moribund at the moment. And the art is great.

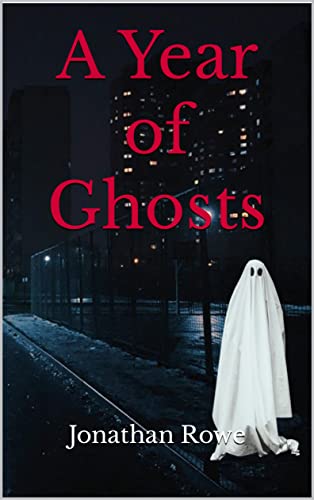

Try it out. But don't go flipping tails! I've not posted in a while and a big reason for that has been the Daily Ghost, a project to write an original ghost story every day for a year. And I did exactly that, completing 365 ghost stories (plus a few extra) and raising money for the First Story Charity that provides writers workshops for less privileged school children. I found some time recently to bring all the stories together in a pretty substantial anthology: the stories might be only 400 words each but a year's-worth of them makes for a weighty tome. You can find A Year of Ghosts on Amazon and there are paperback, hardback and Kindle editions. That's the physical copy on the left and the e-book on the right: take a Daily Ghost home for Christmas A Year Of Ghosts features 365 ghost stories, each one short enough to read with a hot drink but guaranteed to keep you thinking for a cold and moon-drenched night. There are haunting tales of grief and parting, romances of reconciliation and devotion, spine tingling encounters with supernatural danger and satirical romps through the afterlife, mixed with adventure, mystery and mythology. Journey to a haunted planet in the far future, to the ghosts of the Roman Coliseum, follow the machinations of Egyptian necromancers and the legacy of a haunted doll. You will read ghost stories adapted from pop songs, classic fiction and historical celebrities as well as low key tales of life in Lockdown Britain, the testimony of Somali immigrants, a northern pensioner teaching his grandson to be an exorcist and the love song of a Syrian refugee. The book lends itself to a casual reader who can dip into a story here or there, but there’s a huge range here, some of it literary, some mainstream commercial. There are Stephen King homages, a dramatic monologue, a pastiche of Damon ‘Guys & Dolls’ Runyon’s mobster fiction, a string of tales from the 17th century Scottish Borders as well as science fiction, Lovecraftian horror and parodies of Jane Austen and Raymond Chandler. Most of the tales stand alone but there are serials running month to month and of course a season of Christmas ghost stories. RPGers might particularly enjoy the monthly serial 'A Loophole' in which the death goddess Anupet struggles against the machinations of the necromancer Qadaffah, with the necromancer's new apprentice as a pawn in their millennial conflict. Fans of the ghost stories volunteered to narrate them, so there’s a Daily Ghost YouTube channel too with scores of the stories produced as 4-minute audiobooks by voice artists and authors like Nancy Weitz and John Clewarth – as well as myself, learning as I go. Here are two example, including a Christmas ghost story:

David Read narrates The Edge of the Platform and John Clewarth reads The Weeping Mothers There will be more stories on the Daily Ghost site as they bubble up from the unconscious - and some of them will appear in the project that started all this but then got put on hold, a glamorous Second Edition for my Ghost Hack RPG (on Amazon and on drivethrurpg) with lots of campaign ideas in fiction form. Otherwise, my attention is now on the Hedgerow Hack, the RPG of rustic weirdness, time travel, faeries and British mythology. There's some very exciting news about that which I'll reveal in a future post. The RPG products that have been inspiring and distracting me in equal measure - and (fanfare) Ghost Hack is a silver best seller on drivethrurpg

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed