|

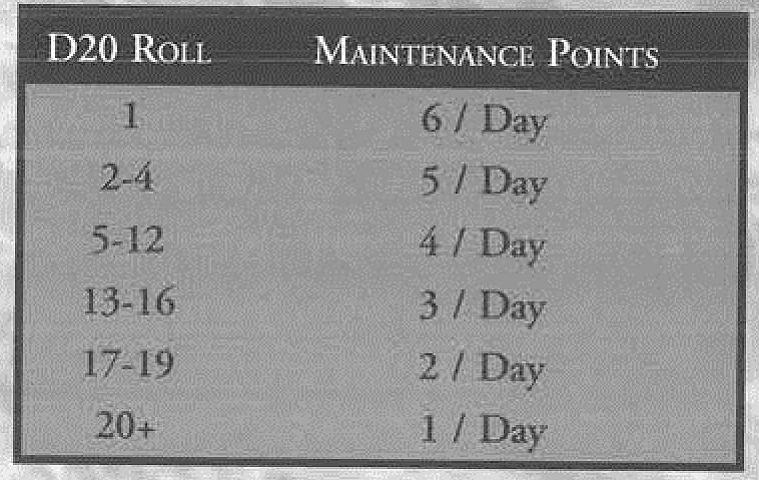

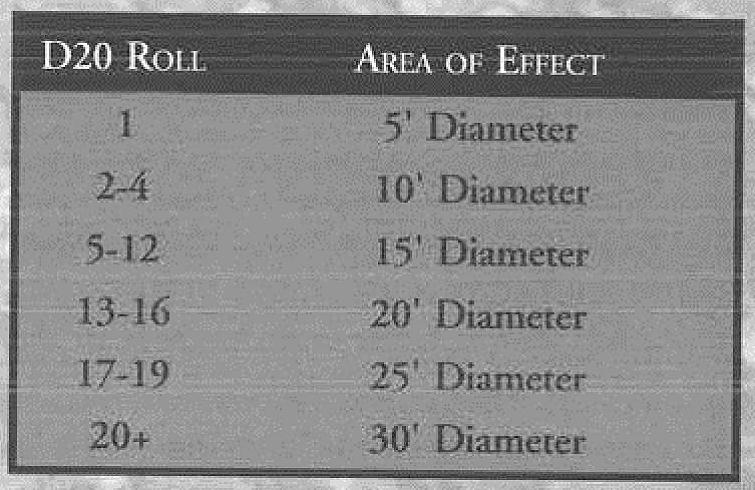

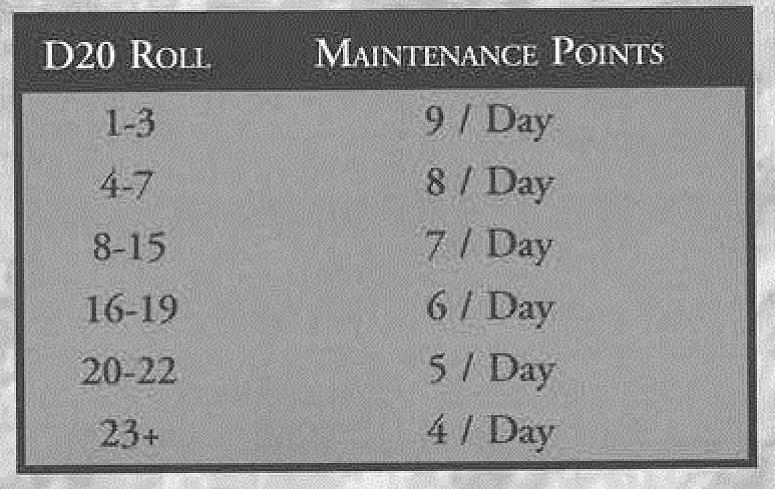

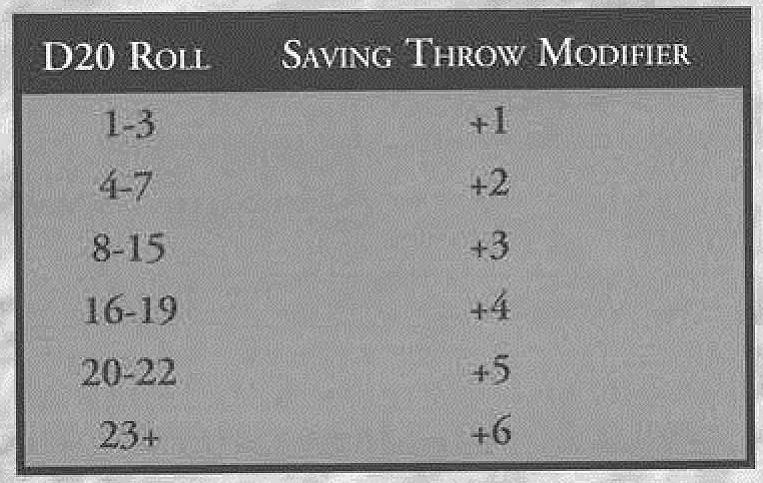

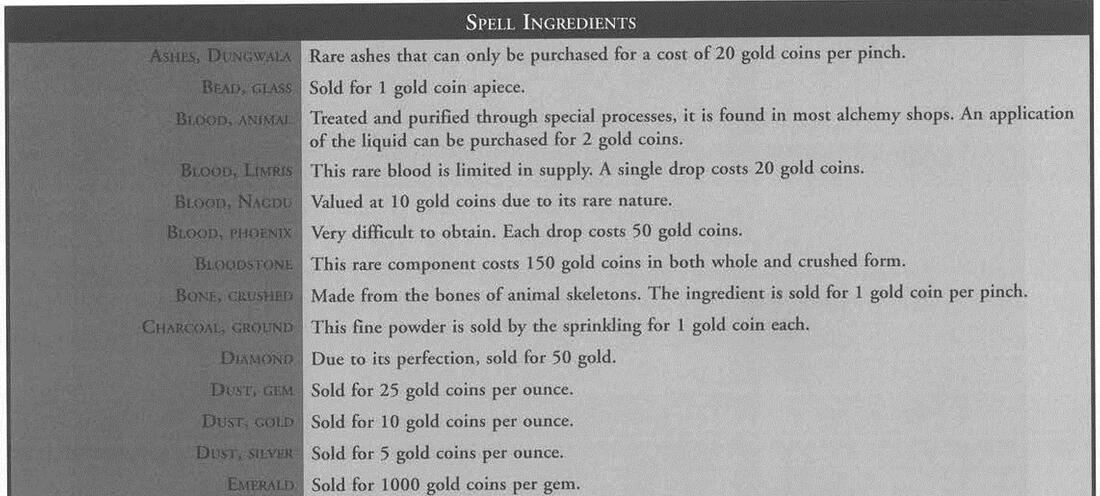

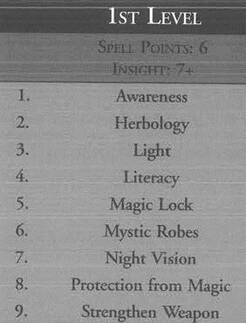

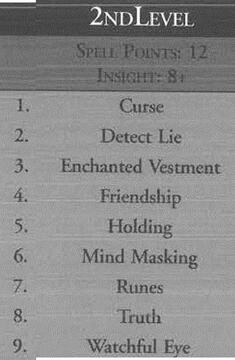

I'm working through the rulebook for the late-'90s fantasy heartbreaker Forge Out of Chaos because it speaks to something in my OSR soul. I've covered the magic system in blogs that looked at simple but restrictive Divine Magic and the more potent but unreliable Attack Magic. A third type remains. Enchantment is a type of Pagan Magic. In Forge, this means it's a sorcerous ability that was once granted (illicitly) to mortals by the gods - in this case by Dembria, goddess of Enchantment - but since the gods went into Exile, mortals have figured out how to do it by themselves. They don't do it accurately or consistently and they have to power it themselves, but it works and you don't need to go kowtowing to Grom or Berethenu to make it happen. Enchantment differs from Attack Magic in that it is permanent, or potentially so. Yes, we're in the business of creating indefinite magical effects: changing form, granting powers, boosting stats, making armour and weapons more potent, reshaping the world around you. In other words, the cool stuff. How it works (or doesn't) As with other sorts of Pagan Magic, you start with a number of spell slots equal to your Intellect and you can choose spells of your current level or (with penalty) the level above, so 1st level casters have access to 1st or 2nd level spells. You have a pool of Spell Points (SPTS) to use, on average around 20, and with a base cost of 6 SPTS for 1st level spells, Enchantment is pretty cheap. When you go up a level in Magic, you usually get another half dozen spell slots and a dozen more SPTS. The big choice is whether to add more spells to your repertoire or improve the ones you've already got. Yes, you can use up a spell slot to re-roll on those Schematics Tables, hoping to improve your spell's area of effect, saving throw modifier and of course the HSE (Hidden Side Effects). Only with these spells you have something else to worry about: Maintenance Points. Paying Maintenance Enchantment spells don't have 'Duration' - they last for as long as you keep paying the Maintenance Cost out of your SPTS. These SPTS that have to be spent on Maintaining spells are Maintenance Points (MPTS). MPTS are determined by those 'schematics' tables too. A 1st level spell could take 6 MPTS to maintain every day; that's a very poor roll and it means the spell costs as much to maintain as it did to cast it in the first place. It could cost as little as 1 MPT per day; that's an amazing roll that you will probably only get if you invested more than the minimum 10 Skill Slots into Magic or if you are re-rolling the 1st level spell when you've reached a higher level. The maintenance costs increase predictably: 2nd level spells cost as much as 7 MPTS and as little as 2; 3rd level costs as much as 8 and as little as 3, and so on. You'll notice though that the maintenance isn't keeping pace with the casting cost. It will cost 18 SPTS to cast a 3rd level spell but, at the very worst, only 8 MPTS to maintain it. The schematics for MPTS and Area of Effect for 1st level spells. Rather than learning an extra spell, you could re-roll an existing one. If you invested 12 Skill Slots in Magic you get +2 on one table. Which table would you apply the bonus to? Schematics for level 4 spells. Even on a good roll, they probably cost as much or more to maintain as a 1st level spell that rolled badly. Instead of learning an extra spell, would it be better to re-roll one of these or try and make that 1st level spell even cheaper to maintain, now that, being 3 levels higher, you get a +6 bonus to split between the tables for 1st level spells? Enchanters, therefore, get powerful fast, since they only need to cast a spell once (usually during downtime) and the measure of their power is how many spells they can maintain. Re-rolling your spells to push down the maintenance cost is therefore a better strategy than going for a wide range of spells that cost a lot to maintain. Problems with Maintenance The rules state that Mages recuperate 5 SPTS for every 2 hours of sleep, up to a maximum of 20 SPTS a day. In other words, sleeping more than 8 hours offers no further benefit. This makes 20 MPTS the sustainable maximum for your spell-load. If they add up to more than 20 MPTS, then you're running down your reserves and eventually you won't be able to cast any new spells or meet the cost of maintaining current ones: you have to let a spell dissipate. The flat limit of 20 SPTS a day seems rather blunt. It's exactly the sort of limit that ought to vary from character to character. The Benefits & Detriments rules (pp17-18) could be extended to cover traits like Heavy Sleeper (+2, regain 6 SPTS per 2 hours) and Light Sleeper (-2, regain 4 SPTS per 2 hours) which could be chosen by Mages at character creation. A Percentage Skill like Meditation (INS x 2) could be used to regain 2 SPTS above and beyond the sleep-limit after an hour of successful meditation. A creatures of Dembria, surely the Dunnar should regain 1 SPT every hour that they spend away from sunlight? It's not clear when exactly the MPT levy has to be paid. As soon as you wake up, whenever that is? But what if you stayed up all night? At dawn or midnight, irregardless? That seems a bit arbitrary. At the hour of the spell's first casting? Too much book-keeping there! It's best to make each Enchanter choose their 'payment occasion' which is the point at which they pay maintenance on their spells. Characters could choose a fixed time (midnight, noon) or a relative time (dawn, the setting of the moon) so long as it's an unavoidable daily occurrence. It makes sense to choose a time that comes immediately after the +20 SPTS you earned from a good sleep but before anything can occur in the day to force you to spend or lose more SPTS: 8am or 9am are sensible choices. Raw ingredients Other forms of Pagan Magic need spell components and it's a big restriction on starting Mages that they cannot afford the components for all the spells they would like to cast. But at least those components are permanent once you own them and they only risk exploding if you "pump" a spell and it backfires on you. Enchantment also requires spell components. The good news is they tend to be a bit cheaper than the ones for Attack Magic; the bad news is they are entirely used up when you cast the spell. This extract gives you a flavour of the spell components on p117. Some you could harvest yourself (although good luck getting Dungwala ashes the hard way). Emeralds are pricey! The lower level (1st-4th level) spells tend to involve the cheaper ingredients of course. Casting Literacy to grant yourself or someone else some languages involves 2oz of gold dust (20gp) and a glass lens (5gp), which is not 'nothing' but a starting Mage could stretch to that. The 2nd level spell Friendship is a sort of 'Charm Person' spell, but with components including 4oz of gem dust (100gp), you're not going to be throwing it around. That emerald is one of the components for the 8th level spell Ego Meld, that lets you steal someone else's body. Considering the benefits (effectively, immortality), it's good value for money. Of course, you might only ever cast a spell once, so the components are a one-time investment. But when five members of your party want Night Vision, this 1st level spell requires 2oz of gem dust per casting, so that will set you back 260gp. Hopefully your friends will contribute to the costs... Casting time & hanging spells Enchantment magic is time-consuming: 5 minutes per level of the spell. Given Forge's maddening 1 minute melee rounds, this means you could perhaps fire off a 1st and maybe even a 2nd level spell if you hung back from combat if no one bothered you (that's a big 'if') but, practically speaking, you won't be casting these spells down the dungeon or on the road. Casting enchantments is a downtime activity. This creates a problem with experience checks that the rules don't address. Normally, Mages check their Magic Skill every time they cast a spell in a crisis situation (i.e. during an adventure), but Enchanters usually cast their spells during sedate downtime. Even if we grant them a check for this, Enchanters just don't cast spells often. In fact, once a spell is cast, they might never cast it again. Enchanters will advance in Magic painfully slowly, if at all. One solution is to grant Enchanters a check to Magic for every spell that is active when they complete the adventure and every spell they pay MPTS for during the adventure. This isn't entirely satisfactory. If the PCs go on a 3-day wilderness quest, an Enchanter with 5 spells active will get 15 checks to Magic (5 on completing and 10 for the spells maintained during the adventure). Another Mage might well not cast 15 spells in that time. On the other hand, multi-day adventures aren't the norm in dungeon-crawler games like Forge and perhaps Enchanters need a slight edge over those Elementalists and Necromancers. Something else missing from the rules is any consideration of 'hanging' a spell that you cast and paid for earlier. Some Enchantment spells do have tactical potential: you might want to cast Friendship on a monster you meet during an adventure - indeed, it's difficult to imagine a situation where anyone will sit obediently for 10 minutes and wait for you to cast a spell like that on them. Curse is another 2nd level spell that only seems to have tactical potential: it imposes a stiff penalty to someone's Attack Value, which is great in combat, except that it takes 10 minutes to perform, by which point a lot of fights are winding down. Who are you going to cast this on during downtime, with its range of 'Touch'? A simple House Rule is to allow Enchanters to cast a spell earlier and leave it 'hanging' until it's needed, whereupon it can be cast like any Attack Magic spell. You use up the ingredients, spend the SPTS and you have to maintain the hanging spell like any other, but you don't get any Skill Check for it until it actually gets triggered. This creates an incentive to cast Curse at home (12 SPTS, 4 oz of gem dust and a crushed lodestone so that's 110gp) and maintain it as a hanging spell, so that when you meet that Ogre you can zap him with the Curse you prepared earlier, claim your Skill Check and probably stop paying maintenance for it (since the point is to make the creature easier to kill, right?). The spells themselves D&D mixes together its permanent effect spells (Continual Light, Magic Mouth, etc) with the wham-bam tactical stuff. By hiving off the permanent magics, Forge creates an interesting option for Mages.

Defensive enchantments are more appealing. Mystic Robes grants you (and only you) an Armour Rating which could go as high as 6 (that's like Plate Mail and for 11gp worth of components, it's a bargain). Protection from Magic offers you a Save Modifier (potentially up to +6 and for only 10gp in silver dust) against Magic. I prefer the Robes, especially since Enchanters can't wear armour. Then there are the 'utilities', like Light (familiar from D&D but at 51gp you might think twice), Magic Lock (what it says, but it can be picked although at a penalty), Night Vision (granted to anyone) and Strengthen Weapon (granting a weapon a chance of not being 'notched' which warriors will clamour for but since it involves 50gp in gem dust they had better pay). The smart thing is probably to pick just a few of these (Robes, obviously; Strengthen Weapon to please your friends; Light, I think; Night Vision too) and use your extra slots to re-roll them to push the MPTS down. If you try to learn 2nd level spells while your Magic level is only 1, you get a -2 penalty on all the schematics. Nonetheless, Curse and Friendship, described earlier, make the Enchanter a dangerous opponent, especially if we use the House Rules to 'hang' spells. Runes improves on Strengthen Weapon by making a weapon count as magical for purposes of hitting mystical creatures. Enchanted Vestment improves on Mystic Robes by granting you 10-30 Armour Points - now that's real protection and cheap for 24gp in components!

These spells have much more potential in campaign play and out-of-dungeon adventures than the other spell lists. High level enchantments allow for all sorts of magical traps and banes to put on weapons, tougher defensive spells, more dramatic utilities, telepathy, invisibility, golem-building, magic item crafting and, at 7th level, Solidify Magic lets you sacrifice dozens of permanent SPTS so that you no longer have to pay MPTS to maintain your crafted magic items: they are independent of you now. The implications of Enchantment: show me the money Enchantment is definitely where the long-term fun is in a Forge campaign. It provides a more logical power progression than D&D spells (Invisibility is hard to pull off), rationalises the creation of magical items and offers a log term goal in Ego Meld (stop ageing, just steal younger bodies). It gives a sense of the texture of a fantasy world where these magical effects are, if not commonplace, at least known about. What's lacking is some sort of payment chart to help you calculate how much NPC Enchanters will charge you to cast these spells. If you don't like Capitalism, stop reading now. Obviously, you have to pay the cost of the components. Friendly Mages (Reaction 76+) might let you provide them yourself, but most will insist on sourcing their own "to ensure quality" and charge you double for their trouble. Then there's the daily fee to the Mage for providing the Maintenance Points to keep the spell going. Back in the '80s, Paul Vernon wrote an excellent series of articles for White Dwarf called Designing a Quasi-Medieval Society for D&D. Vernon constructs D&D economies around the 'Ale Standard' and proposes that a minimum wage labourer ought to be able to slake his thirst at the end of the day for a tenth of his income. Since a pint of ale on the Forge pricelist is 10sp, this means you're paying pack-bearers and torch-holders 1gp a day. On a previous blog, I calculate this to be the equivalent of £50 in modern money. If we assume that a Mage-for-hire considers each of his Spell Points to be worth a day's work for a peasant, we can start calculating. If we assume a Mage-for-hire has the worst maintenance costs based on the schematics, so a 1st level spell requires 6 MPTS/Day, therefore 6gp per day. Yes, the Mage might have rolled better than that and actually only spends 5 or 4 or even 1 MPT/Day, but he won't tell you that. We must also assume the other schematics are at rock-bottom, so hiring Strengthen Weapon gives you a sword that is 50% likely to notch. Let's say you can increase the effect by one bracket by paying the base cost all over again, so 12gp/day gives a result of 45%, 18gp produces 40% and if you want a sword that only has a 25% chance of notching, you had better pay 36gp/day. Then there are the HSE (Hidden Side Effects) and the Mage doesn't want to bear them on your behalf, so that schematic has to be increased by three brackets as standard, just to improve the spell to a safe level: a 1st level spell begins at a minimum 24gp/day and goes up from there in 6gp intervals if you want to improve its effects. Applying this logic, 2nd level spells begin at 28gp/day and go up in 7gp intervals; 32gp/day plus 8gp intervals for 3rd level spells; 36gp/day plus 9gp for 4th level spells; a big hike to 50gp/day plus 10gp for 5th levels spells and 66gp/day plus 11gp for 6th level spells. Let's try a worked example. You visit Melzon the Enchanter because you want Night Vision for a forthcoming quest. The components cost him 52gp so he charges you 104gp. He contracts to provide you with Night Vision for a week. Rolling 1d20, we find that Melzon's Night Vision schematic has a range of 70ft (two brackets past basic) so Melzon charges 36gp/day or 252gp for the week: after components, that's 356gp, thank you very much, payment up front, to see at night like a cat, for a week. If a Forge gold piece is worth £50, then you're paying nearly £18K for this enhancement. Imagine Melzon has a neighbour and rival, Lozeb the Lonely, who has Magic to 2nd level. Lozeb can put Runes on your sword for the week, charging you 200gp for the gem dust needed and 196gp for the week's duration: a Rune-buffed sword for 396gp. Watch out: your sword dissolves when the spell ends. I bet Lozeb insists on providing the sword himself "to ensure quality" and charges double for that, so add in 50gp for the broad sword for 446gp total cost (over £22K). Why not get Lozeb to provide the Night Vision too? Lozeb will charge 2nd level rates for it, even though it's a 1st level spell. After all, why should he rent out his SPTS for anything less than their full value? So his Night Vision will cost you 42gp/day or 398gp (after components) for the week. It pays to shop around, but I bet the Mages don't like that. Lozeb will be cross if he finds you've been sneaking off to that upstart Melzon for a cheaper deal on Night Vision. His contract probably stipulates that you don't engage other Mages while he's working for you and if he finds out that you've done that (and he will find out) then he stops paying the maintenance cost for the spells at once and good luck claiming your money back! This all assumes Lozeb has access to all the spells, which he won't. But let's assume Enchanters-for-hire combine to form business associations so they can cover as many spells as possible and they all charge the rates of the highest-level Mage in the partnership. So if you go to the fancy offices of Gro Finbar Associates (headed up by a 4th level Magic user) you can get all your spell-needs met if you pay as if a 4th level Mage was providing them (even if, actually, it's a 1st level junior partner doing the work). Or go back to Melzon for that Night Vision: he's a sole trader, charging 1st level rates, but he's probably only got 3 or 4 spells to offer. Enchanters-for-hire don't like short contracts. They make their money providing the Baron with Light in his study all the year round, or granting Herbology to a gardener for the whole summer. A bottom-feeder like Melzon might offer Night Vision for a single evening, but I bet Lozeb charges for a week, minimum, and Gro Finbar Associates charge you for a month, even if you only need the spell for a week. A 6th level Mage won't bother enchanting anything for less than a year. This means, if you think your butler has been stealing the silverware and want to put a Truth spell on him, you might only want the spell to be in effect for an hour or two, but Lozeb the Lonely will bill you for a week: that's 378gp, including components, to make the butler confess. It might be cheaper to let him keep stealing... Nonetheless, some spells are very useful. The 3rd level spell Tongues grants you any language. A 3rd level Mage probably insists on charging you for a fortnight, but 618gp is a fair price if you really need to know Ghantu for an upcoming mission (for the record, Gro Finbar Associates charge 1178gp because they bill you for a month minimum). Whew. OK. I enjoyed that. These costs seem right for player characters: cheap enough that spells could be purchased by successful adventurers for particular quests, expensive enough to put magic out of the reach of starting characters. A bit pricey for ordinary people, perhaps? Of course, magic isn't for ordinary people, but these are definitely "adventurers' rates". Remember that, for established businesses like Gro Finbar Associates, adventurers are terrible customers. Yes, they pay cash up front, but that's the only good thing about them. They are erratic customers and they often acquire spell-casting allies or henchmen of their own who service them for free. They purchase a service then disappear off for weeks. Often they don't come back at all. They rarely have good reputations.

No, Enchanters-for-hire want a respectable clientele who need spells maintaining either perpetually or regularly. The Baron wants his favourite boar spear to have Strengthen Weapon on it all year round; the chief constable of the watch wants Night Vision available to him right up until he retires; the merchant prince wants Tongues for the duration of each yearly trade envoy and Magic Lock on his coffers the year round. These people are returning customers and they get much better rates: less than half what player characters pay or even bigger discounts for perpetual enchantments that have been in place for years. And it's worth bearing in mind what enchantments will be enjoyed by well-heeled NPCs, especially if the PCs intend to do something silly, like rob them...

0 Comments

I was reflecting the other day about what a valuable resource 'dungeons' are and how odd it is that, in most campaigns, they don't seem to be owned by anybody. Which is peculiar, really, because dungeons are a powerful economic resource. Not only are they full of treasure, but magic items too. The skin and fur of magical beasts make great adornments for the upper classes and are usually ingredients sought after by mages. Even the arms and armour of humanoid denizens, the vellum and lore of lost grimoires and the access to seams of rare metals have financial value. Why would a local lord allow a dungeon on or near his estate to lie ignored until a bunch of no-account yeoman adventurers finally loot it? Because dungeons are dangerous, is one answer. You can order your knights and serfs to go to war because most combatants in a medieval war don't expect to die in it: the knights can expect to be ransomed and, assuming that disease and arrow-fire doesn't claim them, the peasant levy can hope to leave the battlefield with only bruises and scars. There are fatalities in war, of course, but the majority of combatants survive even on the losing side. Dungeons, on the other hand, are properly dangerous: orcs don't take prisoners, you can be eaten by ghouls, you can be killed by traps, you can be turned to stone! But that doesn't make dungeons valueless. If suicidally brave adventurers are going to descend into a dungeon, the local ruler will want them to be his adventurers, paying him a fee, taking a cut from their loot and certainly first choice of the best magic items, plus samples of rare commodities (lycanthrope fur, demon feathers, powdered gargoyle horn). What is a Dungeon: ruins, wizard sanctums or lairs? Dungeons are an odd concept. The idea that the fantasy landscape is strewn with these large multi-leveled subterranean labyrinths requires some explanation. Many RPG campaigns have abandoned the concept altogether in favour of more naturalistic assaults on fortresses, temples, woodland hideouts and caverns. But the dungeon exerts a grip on my OSR imagination and seems pretty central to the type of adventuring proposed in Forge Out of Chaos, so I'm going to think deeper about what dungeons are supposed to be. In Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the landscape of Cydoril is littered with Ayleid Ruins, easily distinguished by their bright marble surface works and full of slap-footed undead zombies and treasures such as the valuable welkynd stones. Weirdly, the PC adventurer seems to be the only person in Cydoril who realises you can get rich from plundering these places. Original D&D spawned this conceit, perhaps inspired by the Moria scenes in The Lord of the Rings; it's hard to trace antecedents in fantastic fiction for adventures happening in these dynamic labyrinths: elements of Lovecraft, Howard and Lieber? Ursula Leguin's The Tombs of Atuan (1972)? The Zenopus Dungeon, the ur-dungeon created by Eric Holmes for the 1977 'Blue Book' Basic D&D set, is located "on the ruins of a much older city of doubtful history and Zenopus was said to excavate in his cellars in search of ancient treasures." The idea of dungeons as the residue of a more advanced parent or pre-human civilisation has some resonance in history. In the Dark Ages, Anglo-Saxon tribes invaded Britain and discovered the cities of the Romans with their puzzling arches, heated bathhouses and vast plazas. Archaeology shows us that the Anglo-Saxons didn't inhabit these ruins but set up their villages alongside them, doubtless plundering them for stone and treasures while telling stories of the mysterious builders whom they believes to be 'ettins' or giants. One anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet describes such a city like this:

Another rationale for dungeons is that they are the architectural side-effect of stuff powerful wizards get up to. Wizards seem to need to delve underground: perhaps their magics only work at full effect far away from the sky, the sun and stars, from common people - or perhaps they like to be closer to rare minerals in the deeps of the earth or the resting places or summoning portals for eldritch beings. Again, Eric Holmes got here first, with Zenopus the Magician making "extensive cellars and tunnels underneath the tower" which is the proximate cause of the Zenopus Dungeon in Holmes' Basic Rules. The Zenopus Dungeon has been updated and expanded for 5e D&D Gary Gygax took the conception of dungeons in a different direction. For Gygax, dungeons were just lairs, either cave complexes monsters had moved into like squatters (such as the Caves of Chaos in Module B1: The Keep on the Borderlands) or else fortifications built by the monsters themselves to be their home and evil playground (such as the Against the Giants series). Modules B1 (Keep on the Borderland) and G1 (Steading of the Hill Giant Chief) both illustrate the Gygaxian approach to dungeon politics: the player characters are agents of the state and venture beyond its borders to impose sanctions on monsters in their lairs. It could be called a Rumsfeldian model... In Holmes' world, the authorities of Portdown "had a catapult rolled through the streets of the town and the tower was battered to rubble" after which the local dungeon was shunned out of superstitious dread. This fits with Holmes' psychoanalytic interest, with the dungeon representing the repressed id and the adventurers engaged in an exploration of the realm of the imagination that ordinary folks deny - a fine metaphor for roleplaying in general. Gygax's conception is more prosaic, but more alert to the political implications of dungeons. In his scenarios, the authorities send the players into the dungeons, with promises of reward or threats of what accompanies failure: the PCs are agents of the state, bringing law to the strongholds of chaos. As Ron Edwards gleefully points out: "In Forge: Out of Chaos, the very notion of doing anything that isn't treasure-seeking in a dungeon is completely foreign." Yet at least Forge has a clear rationale for dungeons to exist: they are from the God-War or the time before it: the shrines, prisons, mansions or workshops of the gods themselves or their semi-divine servitors. Places like that littering the landscape definitely have to factor in local politics. Are Dungeons like Royal Forests? In the Middle Ages, a 'Forest' meant an area of wilderness set aside for the king or regional lord; originally for hunting but later the emphasis shifted to timber for shipbuilding and war. 'Forests' were usually wooded, but the territory often included marshland, upland heaths, rocky massifs, it was all 'the Forest'. Forests and Dungeons have much in common. Forests are home to dangerous creatures (boar, bears, wolves but also outlaws) and other prestige animals (deer) that count as treasure. There are resources to be harvested: timber of course, but also coal and charcoal and related glassworks, salt mining, honey pasturage, fishing and herbs. But unlike typical dungeons, medieval rulers didn't allow just anybody to wander into a Forest and take advantage of the opportunities there. In 1100, Henry I created the Forest Laws of England, forbidding common people from entering Forests with weapons, cutting down trees, hunting or pasturing animals. Each Forest was overseen by a Keeper, appointed by the King and sometimes (as in Sherwood Forest) the Keeper-ship was hereditary. The Keeper would then hire Foresters (known as Verderers) to police the Forest and arrest trespassers or lawbreakers. These laws and the Foresters who enforced them weren't popular. Lots of rural communities depended on the surrounding woods and heaths for their food and raw materials, but were now forbidden from entering or making use of them. Laws were broken and Courts-of-the-Forest (Swainmoots or Woodmoots) set up to hand out punishments. Courts of Inquisition would be convened if a serious infraction was discovered - such as the carcass of a deer killed by poachers - and as often as not strangers in the community would be singled out for blame. Blinding and castration were the 12th century punishments for poaching the Forest deer. Peasants would have to be pretty hungry to risk this. As time went on, the Forests became a greater source of income for the Crown, so fines replaced mutilations (6 pennies for felling a green oak) and more licences were issued. Keepers, Companies and Dungeon Charters In a quasi-feudal setting envisaged in 'classic' D&D campaigns and in Forge, dungeons form part of the 'Forest' claimed by kings or powerful nobles. A court official (let's call him, without irony, the Master of Dungeons) would appoint Dungeon Keepers to manage the known sites. The Keeper would be a wealthy local landowner: a Squire or Baron, perhaps. The Keeper would in turn appoint serjeants-donjons, dungeon-constables or (my favourite) dinglemen to police the sites. More about them shortly. Of course, the Keeper doesn't want to go dungeon-delving himself: he has a big and profitable estate to run. And yet, the dungeon must turn a profit somehow... Enter companies of adventurers. The Keeper appoints a Company to represent him, granting them his livery and their own heraldic badge. The Chartered Company delves into the dungeon and, on returning, presents the Keeper (and his feudal overlord) with a choice cut of the treasures, including the best magic items. Sharp-witted GMs will realise that this is a very effective way of preventing the creep of wealth and magic items in a campaign. Players get to rake in the money for purposes of XP and use potent magic items while down in the dungeon itself, but on emerging they have to surrender half the cash and the best artifacts to their boss. Unchartered adventurers are poachers. If they evade the dinglemen and get in and out of the dungeon, they had better not convene in the Green Dragon Inn to split their loot, because word will surely get out. The Keeper, whose estate they have trespassed on, will confiscate ALL the loot and add a week in the stocks or a judicious flogging to send out the right message: robbing the dungeon is robbing its lord. The Chartered Adventuring Company will be strongly motivated to assist in the pursuit and add summary justice of their own: they didn't go to the trouble of acquiring their Charter and surrender their most exciting magic items to have a bunch of black market tyros poach from the dungeon right under their noses and run away with the best treasure. In a quasi-feudal setting, the Keeper grants his Charter to an Adventuring Company who reputation redounds to his glory, although valuable gifts would be offered by way of introduction to attract the Keeper's consideration. Eventually, successful Adventuring Companies go national in scale, holding Charters with lots of different Keepers and subcontracting the dungeon-delving out to less experienced groups who have to pay a fee to go adventuring under their badge and livery (and still offering most of the treasure up to the local Keeper). In other words, an Adventurers Guild comes about. Feudal lords delight in their Chartered Companies and their exploits. They expect them to do more than raid dungeons. They have to recount their exploits at banquets, demonstrate their weapon skills at tournaments, accompany their lord on hunts. It's not unlike winning a beauty pageant or a reality TV show: you're in demand. It's tiring being a court favourite and finding the time to get back down the dungeom again can be hard. In an imperial setting, relationships are a bit less personal. A regional governor will assess dungeon sites in his jurisdiction and sell permits to delve into them; the Empire will claim a percentage of the haul and first choice on the magic items. The appointment of a new Governor means the reassigning of permits and some intense negotiations between existing Adventuring Companies . Chartered Companions for and against Player Characters A simple way to start a campaign is for the PCs to be members of a Chartered Company in service to a lord or in receipt of a permit from a regional governor. Perhaps one of them has well-connected family or is related to a celebrated adventurer and can trade on the family name; perhaps someone inherited a fortune and sunk it into getting the Charter. This positions PCs for a dual life, where dungeon-delving sessions are balanced with intrigue storylines at court, where they must re-tell their tales, show off their skills, curry favour with superiors and lovers, make enemies and get sent on all sorts of non-dungeoneering enterprise by their lord or his courtiers: anything from hunting down lost livestock to escorting young maidens around the countryside. In this sort of campaign, rival unchartered adventurers are a scourge and the NPCs that dungeon encounter tables identify as 'Bandits' are probably these people. Enjoy seethng with resentment when your hempen homespun rivals clean out lucrative dungeon levels while you're kissing babies at the village fete; watch them level up faster than you and accrue more powerful magical treasures; delight in revenging yourself when the opportunity presents itself. Alternatively, the PCs are the unchartered adveturers: you are sneaking into the dungeon under cover of darkness, evading the dingleman and his henchmen, meeting at a secret trysting place to divide the loot, coming up with far-fetched tales to explain your wounds and scorched clothing. Most of all, you are running scared of the Chartered Company: those smug, lazy playboy-adventurers who get all the glory and who dog your footsteps, trying to expose you at any turn. The stocks or the scaffold await you if you're caught - unless of course you get wealthy enough to earn your own Charter. Meet the Dingleman The Dungeon Keeper doesn't want riff-raff poking around in his dungeons. Peasants in search of shelter or loot will probably get themselves killed or else provoke the subterranean monsters (pretty much the plot of Beowulf, where an escaped slave steals from a dragon's hoard and the indignant reptile visits destruction upon the tribe of the Geats). But it's not just that. It's even worse if those enterprising peasants succeed, and emerge from the dungeon as hardened veterans, with magical equipment, spell books and a heightened sense of themselves. Such 'heroes' aren't going to be content back behind the plough. More likely, they're the ringleaders of the next Peasant's Revolt. Even if they don't revolt, peasant-adventurers promote something just as bad: social mobility. The ruling classes in a hereditary aristocracy don't want to be mixing with ploughboys and dairymaids who made their fortune plundering dungeons. This means dungeons must be policed and the dingleman or Dungeon Constable is the policeman. Probably, this person is the landowner nearest to the dungeon entrance, drawing an extra stipend from his lord for these duties. It might be a hereditary position or it might be offered to a retired war hero or adventurer, complete with a gift of land and a nearby cottage or tower from which to keep an eye on things. Obviously, the dingleman chases trespassers away from the dungeon entrance - or, in the case of large armed companies, takes a careful note of their identities. He's probably a capable warrior or magician and has some henchmen (perhaps his sons) and some big dogs to back him up. More than this, the dingleman's patrol probably includes the upper dungeon level too, or at least the corridors and rooms around the entrance. The dingleman knows about the traps and some of the monsters and might have some tricks (high pitched whistles, unpleasant-smelling incense) to chase away wandering monsters like slimes, rats, gelatinous cubes and mindless undead.

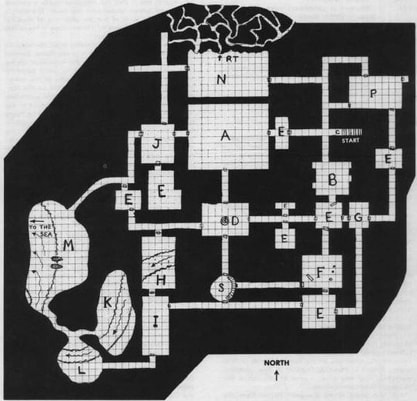

If the post is hereditary, some of these monsters knew the dingleman's grandfather and their working relationship can be quite sophisticated. Perhaps the Goblins tip off the dingleman when they're planning to raid the surface, so he can warn nearby farmers to lock their doors or spend a few nights safe in the town inn while their barn is being ransacked. Perhaps the dingleman tips off the monsters when the Chartered Adventurers hove into view: they can retreat to a lower level or hide away their children and womenfolk. That's what makes dungeon poachers so destructive: by descending unannounced on a dungeon and, by slaughtering the unsuspecting monsters, they damage the delicate trust-networks that have grown up around the site. I like to imagine Dungeon Hunts are popular with the more eccentric nobility: some young lordling and his entourage descend into the dungeon, clatter around harmessly for a few hours and do battle with something they can manage and emerge as monster-killers. The dingleman curates this experience, much like foresters set up a hunt by locating a likely quarry. The local monsters have to be forewarned and clear out ("You don't want to go messing with the young prince, he's well connected!") and in return point out to the dingleman the location of a suitable quarry ("Human, on the third level is predatory wyrm that devours our scouts: it would make a fine trophy for your prince!"). Of course, sometimes the dingleman really is working for the monsters, especially if there's a mesmerising Harpy on the second level that's turned his mind. What ought to be a safely-curated day of underground hunting can go badly wrong. This is the sort of occasion that sends in the player characters (even if they're unchartered) on a rescue mission. Dinglemen for and against Player Characters A friendly dingleman is the best source of likely-to-be-true rumours that a Chartered Company of Adventurers can have. He might be on hand to help with hauling large treasures out of the dungeon and willing to escort the party to a jumping-off point within the complex and offer directions from there ("These steps go to the third level; there's a room of glowing pillars, they say, and beyond that a witch's lair: she turns folks to stone!"). Naturally, in return the dingleman expects a share in the party treasure and perhaps the choice of a magic item. This, and also respect and fair language. If the party behave high-handedly, well, the dingleman can be much less helpful: rumours will be of the less accurate sort, directions vague, assistance grudging. If relations really break down, monsters will have uncanny foreknowledge of the party's approach. Unchartered adventurers usually avoid the dingleman at all costs. In a feudal system, the dingleman's loyalty to his lord (and fear of the punishments for dereliction of duty) makes it hard to bribe him or talk him round. He might show up to rescue PCs from a tight spot, only to escort them to a gaol. In other settings, the dingleman might be more of a jobsworth, amenable to a bribe or even taking a liking to young adventurers. Any assistance he offers will have to be secret though: remember the Chartered Adventurers and their sense of grievance? Best to turn a blind eye and leave it at that. I'm charmed by the idea of dinglemen: I'll make a point of incorporating on into my next dungeon. Here are some final thoughts about how a dingleman might function in a well-known dungeon: the Zenopus Dungeon by Eric Holmes. The Zenopus Dingleman You can read the original Zenopus Dungeon here, or look at my version for Forge Out Of Chaos or buy Zach Howard's 5th Edition adaptation for $1.99. I analyse the dungeon in an earlier blog.

Brubo patrols the area around the dungeon entrance to chase away trespassers but won't offer violence. He's too honourable to bribe. He will direct Chartered Adventurers to the stairwell and cackle about the endless corridors, the perilous graveyard, the sunken city of pre-human origin: he's great for setting the tone and functions as a Threshold Guardian (in Joseph Campbell's neo-Jungian terminology). Inside the dungeon, Brubo can be encountered as a Wandering Monster. He can help the party out against undead and carries a string of sausages to distract Giant Rats: in terms of Campbell's monomyth, he's a Helper and Mentor. Of course, he has been charmed by the Magician in Room F: he will direct or chase adventurers away from that area and fight to protect his master. On the other hand, he's a keen enemy of the Pirates in Room M and will assist even trespassing unchartered adventurers against them. If Brubo apprehends trespassers, they face a night in the stocks and confiscation of all treasure. If they keep returning to the dungeon, they will earn Brubo's grudging respect and he will increasingly turn a blind eye to their movements, especially if they deal with the Pirates. Post Script: I've added Brubo to my adaptation of the Zenopus Dungeon for Forge over on the Scenarios page.

I've spent time looking at the apocalyptic mythology set out in FORGE OUT OF CHAOS, as a basis for its system of Divine Magic, an explanation for its races and clerical classes and its (rather overlooked) implications for fantasy world-building. Time now to take a deep dive and explore the mythology on its own terms. Just what are its values and themes? After all, a myth, even a careless and derivative myth, is a tightly packaged bundle of meanings - it's an answer in story form to the fundamental questions of existence. So what answers do the myths of Enigwa's creation, the war between Berethenu & Grom and the Banishment provide? Tolkien & Kibbean Creation Myths

The Kibbe Brothers have clearly taken points from Tolkien. For example, in The Silmarillion (1977), Tolkien sets out the Ainulindalë (the Music of the Ainur) and Valaquenta (the Story of the Valar). A mysterious creator-God named Iluvatar brings the world into existence. Similarly, the Kibbes introduce Enigwa as the world-creator. World-creation is a task that Tolkien's Iluvatar shares with his created servitors, the Ainur or Angels. He delegates creative power to them, but one of them, Melkor, the greatest of angel-kind, pursues his own vision, disrupting Iluvatar's harmony, to which Iluvatar responds by deepening and complicating his symphony with richer themes to incorporate Melkor's rebellion into a satisfying whole. The Ainur are then given the opportunity to enter their creation and live within it as the Valar (Powers), i.e. embodied angels or earthbound gods. In the Kibbean creation-myth, Enigwa creates the world without collaboration: "he personally forged each mountain, planted each tree, chiselled each river." He then creates the gods and inserts them into his world so that they can "explore their father's creation.". Enigwa withdraws and the gods, left with autonomy, start to develop diverging agendas. "Although most were good at heart, some became chaotic, others aggressive, still others lustful and greedy." The gods fall into discord and Enigwa has to return and unite them in a shared project. There are apparent similarities here (creator-God, lesser divine offspring, rebellious autonomy, the Creator restores harmony). Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created a myth that is purposefully analogous to the Christian one. Iluvatar is the Judeo-Christian God who creates free willed agents. He then adapts his creation to their free-willed choices, responding to their deviance with deeper and richer harmony, drawing beauty from ugliness, redemption from rebellion, holiness from hardship. Melkor of course is Lucifer, the errant angel. Tolkien's creation myth demonstrates why the creation of free-will necessitates the creation of a world, and a world which contains difficult features, but a world in which transcendent goodness is possible. The Kibbean myth is not Judeo-Christian but Darwinian. The Creator-God brings into existence, not free-willed minds, but a material world. Free-will emerges from Enigwa's absence, as rational beings explore the world through trial-and-error. It's a Behaviourist myth of learning through experience, of positive and negative reinforcement, with the gods developing in different directions, like B.F. Skinner's rats in a gigantic cage. There's no suggestion that Enigwa intends his divine children to evolve into these diverse personalities or even that he foresaw it. Although the text describes Enigwa as a "kindly father" he functions rather more like a dispassionate scientist: God-as-detached-observer. Unlike Iluvatar, he doesn't incorporate free-will and rebellion into his overall creative vision, he merely suppresses it when present and allows it to flourish when he is absent. Noxious characteristics in the world (deserts, miasmic swamps, volcanic rifts, predatory animals, parasitic wasps, diseases) are part of Iluvatar's compromise with free-will, but are outright distoetions of Enigwa's purposes, put there by his errant children. Free-willed agents don't seem to be part of Enigwa's plan so much as a surprising side-effect of it. Evil emerges from the absence of God or the failure of his foresight. In Tolkien, God's foresight is absolute and even Melkor's rebellion becomes the means by which a deeper, nobler and more surprising moral order emerges: "And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined." This distinction, between Tolkien's divinely ordered but morally complicated creation and the Kibbes' disordered and lawless creation, leads to a different conception of Humanity. What a piece of work is man In Tolkien's myth, the created world awaits the birth of Iluvatar's physical creatures, the Elves. Most of the history of Middle-Earth is the history of the Elves: their journeyings, songs, romances and craftsmanship and - later - their noble but doomed war against Melkor/Morgoth. In Tolkien's Christian imagination, the Elves represent an Unfallen Humanity, Adam and Eve's children without original sin: immortal, virtuous, the peers of angels, the icons of God. Crucially, they're not boring. Immortality and goodness are compatible with having adventures, taking risks, experiencing peril, making mistakes. The Oath of Fëanor drives some Elves to to dreadful things, but apparently without malice. Humans appear later, a sort of divine afterthought. They are mortal, frail, unlovely and lack innate wisdom. They have one thing that Elves lack: the Gift of Death. An odd sort of gift, but one that relates them more fully to the Mystery of God than the Elves and even the Valar (who are bound to the world even if their bodies are slain). Humans are a paradox: the furthest from the divine in terms of innate power, the closest in ultimate destiny. And of course, mortality makes their brief lives into possible vehicles for self-transcendence. The courage and hope and faith of Humanity exceeds anything Elves can experience. This places Humanity in a clear Christian framework: humans are simultaneously central and peripheral, exalted and lowly, the highest and the lowest of creatures. It's an insight Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Hamlet:

In Christian thought, humanity has no innate value; humans are central to the drama of creation only insofar as they are loved by God, and loved insofar as they are sinners and suffer. In the Kibbean myth, Humanity is created by the gods as a shared project and entrusted to them by a departing Enigwa: "Help them learn of the world and its wonders. Instruct them as teachers and watch over them as shepherds." There seems to be folksy wisdom in what Enigwa does. To unite the querulous gods, he gives them a joint project and duty of care. One is put in mind of a parent giving squabbling children pet guinea pigs or hamsters and saying, 'You'll have to take turns feeding and cleaning them!' Regardless, Enigwa does not seem to know his children well. Once he departs, they fall to fighting again and this time their human pets are repurposed as warriors. Others gods come to Humanity's aid, but since they too employ humans as soldiers and raw materials for their ventures into species-creation, their advocacy is equivocal at best. Moreover, Enigwa leaves the gods with a parting instruction: a prohibition on teaching Magic to humans, "for Magic is the power of the divine alone and not meant for the ungodly." Of course, the gods violate this ban pretty quickly, promoting their human lieutenants to necromancers, elementalists and beast mages. This stands Tolkien's conception on its head. Humanity is now a central project on Juravia: the ur-species from which all other fantasy races are derived. However, there's nothing of the divine about them and no transcendent mystery to their destiny. They are a biological instrument, intended to unite the gods but retooled as weaponry. Humanity finds itself at the tail-end of a long story, present in the world to serve purposes not of its own choosing and shaped by contingencies set in motions aeons earlier. This is a truly Darwinian perspective. Insofar as there is a Fallen race in Kibbean mythology, it's the gods themselves, who renege on their duty of care and violate the prohibition on teaching Magic. Tolkien's rather nuanced Christian sensibilities appear here in a very debased form. There are people (not usually Christians themselves) who imagine the Genesis myth to be the story of an irresponsible Creator placing his human wards in an experimental environment with only cryptic guidance and allowing them to corrupt themselves through poor choices, then punishing them for disappointing him. This is certainly a good description of how Enigwa treats his children, the gods. In the last blog, I suggested the Kibbes had created a great myth for the Enlightenment: a myth for secular humanism. The gods experience temptation, fall, wreck the planet and meet with divine judgement. There's no repentance, only Hell or Banishment. Then they're gone. Humanity and its sister-species are left in possession of a ruined world, like tenants-turned-homeowners after the bank forecloses on their landlords. Tolkien conceives humans as bound to God through the inscrutable intimacy of Death and uses his Elves to explore ideas about what an Unfallen Humanity would be capable of (and therefore what fallen humans should aspire to). The Kibbes conceive humans as the product of an unguided evolutionary process, perhaps set in motion by God, but not controlled or monitored by him. In the Kibbean mythology, Death is simply the end and the worst thing there is. The shortcomings of the gods expose the destructiveness of religious ideologies: Berethenu, Grom and Marda are not viable role models. Religion was perhaps meant to instruct and shepherd humanity, but it failed in that and actively abused people until finally losing its grip with the advent of a godless world.

The mythological is political Of course a good myth doesn't have just one single interpretation (that would make it a mere allegory). There's a historico-political strand to Tolkien's mythopeia and a surprising (and creepy) political subtext to the Kibbes' mythopoesis too. Tolkien's Middle-Earth is meant to be our Earth viewed through a mythic lens. The parent civilisations of Classical Antiquity (Numinor) and Biblical Israel (the Elves) are represented as devolving into the murky Dark Ages of lost Arnor and waning Gondor. Gondor is Byzantium, the successor state to Greco-Roman civilisation and Biblical Israel. The Dunedain Rangers and their wards, the Hobbits of the Shire, represent the barbarian peoples of Northern Europe. They haven't inherited the physical accoutrements of the golden age cultures, but they are the custodians of its true values (liberty and Christian conscience). That's why "all that is gold does not glitter" in Bilbo's poem. Tolkien's understanding of Christian civilisation is pretty chauvinistic. Modern historians will point out that Islamic civilisation (very much 'the bad guys' in Tolkien) is just as much the custodian and conduit of Classical and Biblical culture as the Normans, the English and the Franks. The Kibbean myth can be interpreted historically too. Do the gods represent the imperial and theocratic powers of the Old World? Is the Banishment the First and Second World Wars, which toppled their empires and brought about the emergence of republican America, with its separation of Church and State? Berethenu is the British Empire, Crom is Soviet Communism and Necros is Fascism. Humanity, in this reading, means Americans. I feel pretty sure the Kibbes intended no such thing, but their myth does have an unpleasant aspect to it. I mentioned before that, for the Kibbes, Humanity is the ur-species; the Elves and Dwarves, the Ghantus and Merikii, all the lizard-folk and weasel-folk, they are all mutated Humans. In a sense, they are to Humanity what Tolkien's Orcs are to Elves: blasphemous remodelings of the original. Nothing could be further from Tolkien's thought, where the Elves are the Firstborn of Iluvatar and the other rational species (hnau as C.S. Lewis calls them) such as Dwarves and Ents are the independent creations of the Valar. Each has its own integrity and destiny. Not so in Juravia, where Humans are the true form and the other races are simply knock-off copies. Gary Gygax referred to the PC races in D&D as "demi-humans" but in Forge they really are demi-humans. Then you look at the illustration on p12 and - oh dear! - it seems that "the image of Enigwa" isn't just Human, but white people. Then you wonder, what about the lesser, corrupted races, the intellectually challenged Ghantus and the lizard folk and the ghost-faced Dunnar: who are they representing? Awkward... Of course, the Kibbes didn't mean to stumble into the back parlour of scientific racism, with its categorisations of 'lesser races' set against a White European norm. They were just weaving an entertaining tale, a "fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus" as Ron Edwards says. But it does go to show how loaded myths are, and how perilous it is to go tinkering with them. Easy to resolve. I like to imagine that the Kibbean myth in the Forge rulebook is just told from a human-centric perspective and that the Elves claim that they were the original species and the Dunnar claim no, they came first, while the Jher-em think everyone is descended from them. The true appearance of that original species, created by Enigwa and his divine children in a rare moment of harmony, will never be known.

Previous posts discussed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic and analysed its apocalyptic mythology, in which the gods are all banished or consigned to Mulkra (Hell). This mythology, which gets pride of place at the very start of the book, was subjected to Ron Edwards' withering critique about fantasy heartbreaker RPGs indulging in "dumb names" and "un-fun strictures" for clerical characters. Edwards also complains that, despite their enthusiasm for myth-making, these games don't develop fantasy religion any further than a "direct correspondence with player-character options (as opposed to societies or organizations)." In other words, the myth-making just offers an explanation for fantasy races and clerical spells, but gets forgotten about as soon as this is over and done. Let's take a look at that. Life after the Apocalypse The Kibbe Brothers make a substantial and rather imaginative effort to sketch out a fantasy mythology for Juravia, involving a benevolent but absentee Creator and a family of flawed and compromised divinities, culminating in an apocalypse where the deities are judged, found wanting and banished. The implications of this are huge. Most fantasy mythologies - and many real world ones - propose an apocalypse at some future point. The Norse anticipated Ragnarok when the gods will fight the giants and lose. The Aztecs feared something similar and made blood sacrifices on an industrial scale to delay it. The word 'apocalypse' means 'revelation' and is the original name for the Book of Revelation in the Bible, an obscure rant in uncouth Greek where a prophet named John describes (with great relish) the ghastly things that will accompany Christ's Second Coming in a series of mind-bending dreams involving giant angels, many-headed monsters and environmental catastrophes.

The implications of this are huge and not just for who clerics get their spells from. Consider the explanatory power of religion. In ancient cultures, disease and adverse weather, crop failures and pestilence, these were explained by the activities of the gods, either through their negligence in making the world secure against chaos or their active malevolence. That's why you prayed and sacrificed: to get the divine 'on side'. This affected social structures. Society was set up to mirror a divine order, with a monarch supported by a priestly class, receiving authority from the gods to rule and resist chaos as their semi-divine representative or partner. Defying the ruler was defying the gods and siding with the powers of chaos, disorder and death. This focus on divine order doesn't just lead to rituals of kingship, titles and authority; it imbues the calendar with mean, allocating feasts and fasts to different seasons and drawing communities together to reenact the great myths in worship and art. Social order emerges from this and also social distinction: tribes that honour strange gods and indulge in senseless rituals are the 'Other' and conflict between tribes becomes part of the divine order too: warfare becomes a religious duty and death in battle a religious sacrifice. Now let's look at Juravia. What authority can kings and princes cite when some enterprising peasant asks (Monty Python style), "Well how come YOU get to be king then?" What institutions exist to prop up their rule with a claim to possess, not just might, but right? How should the inhabitants start to regard each other, now that it is known as an objective fact that their differences of culture and race (bird people, reptile people, giant one-eyed apes) are the result of self-interested power-grabs by a clan of squabbling super-beings who were all equally criminal in their actions. If praying doesn't solve anything, but the world still contains danger, bad luck, unfairness and outright wickedness, what are thoughtful people supposed to do about it? Actually, it's not hard to answer that. You only have to look at our world for answers. We too experienced a widespread cultural collapse in confidence in religion to provide the rationale for politics, social order and morality. It was called the Enlightenment. Life after the Enlightenment The Enlightenment roughly corresponds to the 18th century in European history and involved the light of reason and science driving out the darkness of tradition and superstition. There were lots of causes. The Protestant Reformation had helped make religion a private rather than a public matter and the bloodcurdling Wars of Religion shaped a view that God had no place in politics and perhaps no place in ethics either. Science arose to claim an alternative explanatory power to religion and leaps in technology seemed to validate scientific claims to understand the true nature of the universe. Forge's legendarium has similar forces at work. The God-Wars serve to discredit the gods and their worship, revealing that the gods were neither wise nor good and that they are no longer able to answer prayers. After the Banishment, mortals work out the principles of magic and learn to cast spells without divine assistance: a close analogue to the rise of science. Magic seems to be a natural (and morally neutral) force in the universe which can be manipulated by those with the intelligence, willpower and the right tools. The gods were just better at it than anybody else. The thinkers of the Enlightenment and subsequent centuries were faced with the problem of living in an imperfect and unjust world, without the assurance that God ordained it to be this way or would intervene to improve it. This is similar to the inhabitants of Juravia, left with a world with all the normal dissatisfactions (poverty, disease, inequality) plus marauding monsters. Fantasy Democracies and other solutions The most influential solution proposed by Enlightenment thinkers was human rights and democracy. In the absence of God, we have to be gods to one another and treat each other as gods. Every individual is accorded a transcendent worth and their consent (in some form) is the only ethical justification for the exercise of power and the continuance of unequal social arrangements. You would expect a world like Juravia to start throwing up democratic republics, where having the status of a rational agent (regardless of your appearance: bird-person or one-eyed gorilla) entitles you to vote. These republics wouldn't necessarily be very stable or even peaceful places. Democracies can be fissiparous and inclined to go to war, especially against non-democracies. You would expect slavery to be a raging controversy and some races might be unfairly deemed 'irrational' and unworthy of the franchise (I'm talking about those dimwit Ghantus). But democracy isn't the only Enlightenment solution. The fact that democratic republics can coexist so easily with the unjust social arrangements that preceded them explains why some people find them no solution at all. Communism offers another way, especially since the Banishment has created a Year Zero and an opportunity to cast down and re-make all social institutions. Agrarian fantasy societies might find Communism much more amenable than democracy, especially if they have to knit together different (and formerly inimical) races. It's easier to get the orcish Higmoni and the avian Merikii to coexist if you take all their possessions off them and redistribute everything. I imagine the frail but empathic Jher-em weaselfolk would excel as Communist commissars. The daylight-hating, magic-detecting Dunnar would rise through the ranks as well, leaving Elves and Dwarves to toil in the mines and collectivised farms. Then there's ethno-nationalism; let's just call it Fascism. Even if the gods are losers and now ineffective, having a specific creator binds fantasy races into a shared narrative, having a place where they belong and a way of life that is ordained for them: they are not just a species but a Nation. "We are Merikii, the People of Marda, and we were granted this land." Nations need borders and a strong sense of who is in (your compatriots) and out (foreigners). At its best, this produces communities with a powerful sense of identity and distinctive culture that is not subject to any sort of rational critique. At it's worst, there's institutionalised racism, enslavement of lesser species and genocide. Finally, there's the true flipside to the Enlightenment: religious fundamentalism. Not everyone accepts the gods are gone, no matter the evidence. Fundamentalism thrives on conspiracies and messiahs: either the gods are hiding themselves (as a test of faith, no doubt) or are shortly to return (to reward those who stayed loyal). Fundamentalists hate the democratic republicans, Communists and Fascists equally: they've all replaced religious worship with a false idol (the will of the people, the common good, the nation). In Juravia, where specific gods created specific races, Fundamentalism might coexist with some forms of Fascism. Maybe the Sprites await the return of Omara to rule over the pastures where she established her little people. In return, the Enlightenment political institutions distrust Fundamentalism. Democracies try to lock religion out of politics (either with a strict separation of church and state or by neutering religion as an established church that serves the state); Communism tries to expose it as a sham; Fascism might patronise some local cults while persecuting other foreign ones. Outright Atheism emerges from this debate. After all, why suppose the old stories of the gods are even true? Maybe Necros was just a way-powerful Necromancer and Dembria an Enchanter. They bamboozled people into thinking they were divine then got their comeuppance. "I'm sure there's a magical explanation for all this, Mulder." Dembria (Enchantment), Kitharu (Nature) and Marda (Beasts) Where does that leave the 'churches' of Berethenu and Grom? After all, these cults have some evidence (in the form of clerical spells) that their gods are still real even if they don't intervene. As sketched out above, some states will try to privatise these cults (whatever you do in your own time...) and others will assimilate them (this document makes you a state-licensed activist of Grom) or repress them (was that an act of ideologically-unsound magic, Friend Citizen?) and in some ethno-nationalist enclaves the cult IS the state (the Dwarvish See of Berethenu welcomes careful waggoners). Atheists will regard 'divine magic' as a hoax: ordinary Pagan Magic with delusions of grandeur. Of course, for ordinary people, there's ordinary superstition. It never hurts to offer a prayer to Kitharu before a sea-journey: if the god still has the power to make it tempest-free, so much the better; if not, what did it cost you? But I can't help feeling that a world like Juravia would be intolerant of such things. Once you reject religion, you don't tend to retain an affection for it, even in its quaintest forms. Since Kitharu infested the deeps with sea monsters and then cleared off, leaving the mess behind, I doubt sailors or the rulers of maritime empires would be sentimental about him. If you want a safe voyage, hire an atheist Elementalist; if you want to tell yourself comforting lies about Kitharu, stay on land. The culture of moderation and litigation The Kibbes' mythology seems to teach other lessons its writers don't appreciate. It condemns any form of extremism. Left to their own devices by Enigwa, the gods pursue their own agendas, becoming more and more extreme until, unable to compromise, they go to war. Obviously, Grom and Necros are the villains, but the tale of Berethenu is poignant. The god of Justice, Berethenu breaks all the laws he was trusted to uphold. He goes to war on the Triumvirate, he shapes humans into his Dwarvish servitor race, he teaches magic to mortals. Of course, he does so for high-minded reasons, but so what? When Enigwa pronounces judgment, Berethenu's own inflexible scruples make it impossible for him to repent: he condemns himself to eternity in Mulkra. The moral: there's no ethical difference between a monster like Grom and a paladin like Berethenu; both end up in the same place. One imagines that, even centuries later, the citizens of Juravia feel discomfort around a Berethenu Knight. Sure, it's nice that they give to charity. But the defining myths of this world condemn what they stand for. The myths also condemn laissez-faire individualism. Enigwa is culpably irresponsible for leaving humanity at the mercy of the squabbling gods. If the gods themselves cannot be trusted to run the world without the firm hand of higher authority guiding them, what chance do ordinary people have for making the right decisions unassisted? One suspects Juravia is a world of authoritarian regimes where people look to strong leaders and distrust liberalism. Even democratic republics can be authoritarian, especially if they are intensely legalistic. The law makes a great surrogate for religion in secular societies because it tries to do the same thing as religion: establish order and the limits of what is acceptable, create the illusion of control over the vicissitudes of life, pronounce judgment by rewarding the virtuous and punishing the wicked, connect people to the past through precedents and each other through contracts. I wouldn't be surprised if Juravian adventurers need to be legally recognised professionals, rather Elizabethan players, subject to the bureaucratic whims of a Master of Dungeons who hands out and revokes the licenses to plunder any particular tomb, cavern or mine, Or just ignore it Ron Edwards notices that Forge Out Of Chaos ignores all of these considerations. He actually takes it as a point in the game's favour that "this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." The Kibbe Brothers seem to bear this out. No sooner have they described the Banishment than they are alluding to the persistence of entirely conventional religion in Juravia. Apparently "sailors and coastal provinces hold festivals in [Kitharu's] honour" (nothing strikes me as less likely) and "the Festival of the Eclipse is still held in [Dembria's] honour" (weird, since Dembria's blotting out the moon is what unleashed the undead upon the world) while "holidays and ceremonies are held in [Omara's] honour" (fair enough, farmers need holidays, but why would they honour a goddess who cannot guarantee anyone a good harvest?). The World of Juravia Sourcebook (2000) makes it clear that conventional polytheistic piety holds sway in Juravia. It's like the Apocalypse never happened. But I like the Kibbes' apocalyptic myth - or bits of it anyway (I'll discuss the unfortunate bits in the third and final blog in this series). It seems to me that there ought to be a fantasy setting properly based on it.

Maybe I'll end up designing it myself... In a previous post, I analysed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic, used by the worshipers of Grom and Berethenu. This led to details about Forge's odd mythology (these are the only active deities and both are imprisoned in the subterranean fiery hell of Mulkra) and Ron Edwards' observation that it is typical of 'fantasy heartbreakers' to belabour mythological backdrops but ignore the role of religion. To be fair, of all the heartbreakers that he reviews, Edwards concedes that "the best of the bunch is Forge: out of Chaos, probably (as I read it) because this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." Edwards sketches out a brief checklist of the way these games travesty religion while obsessing over mythological settings:

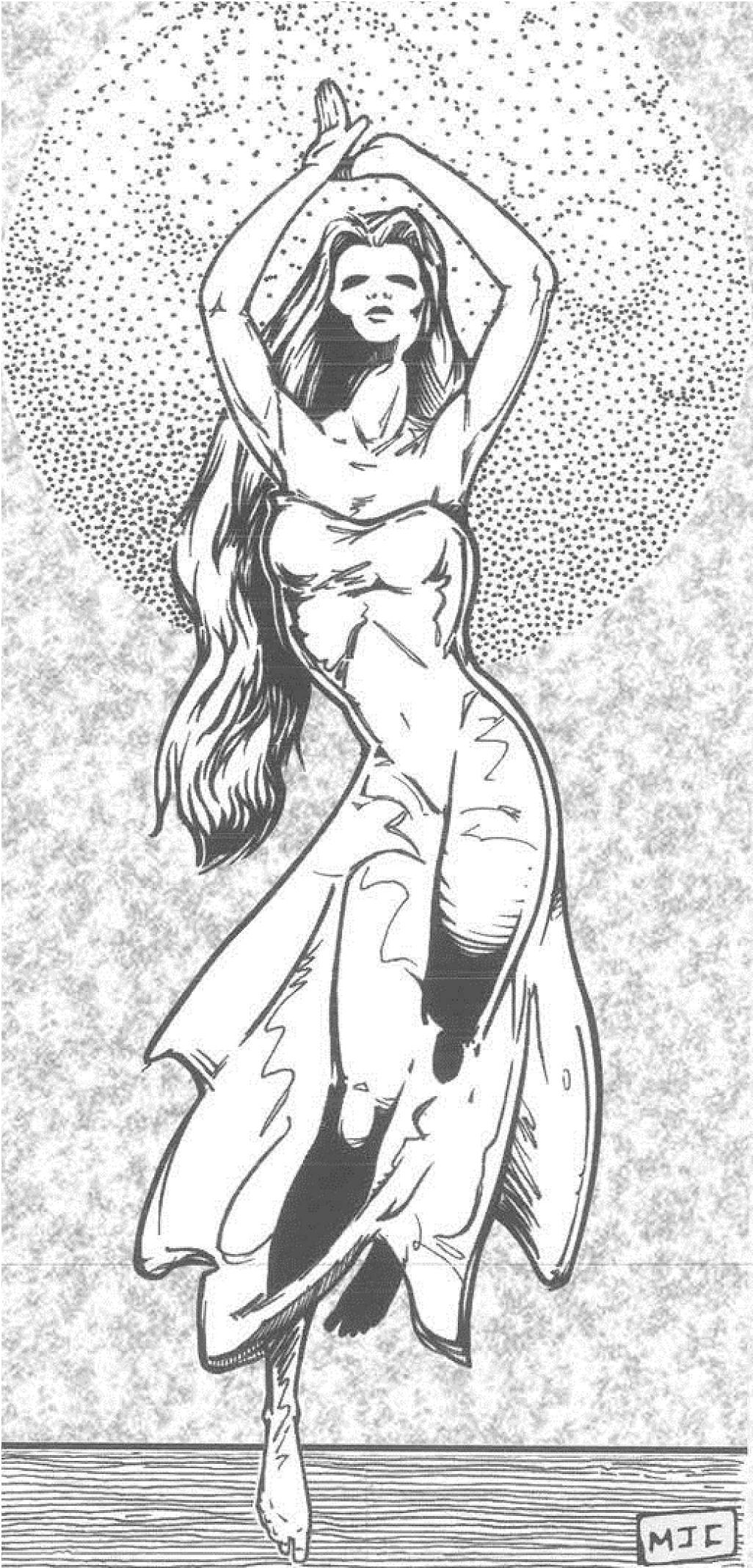

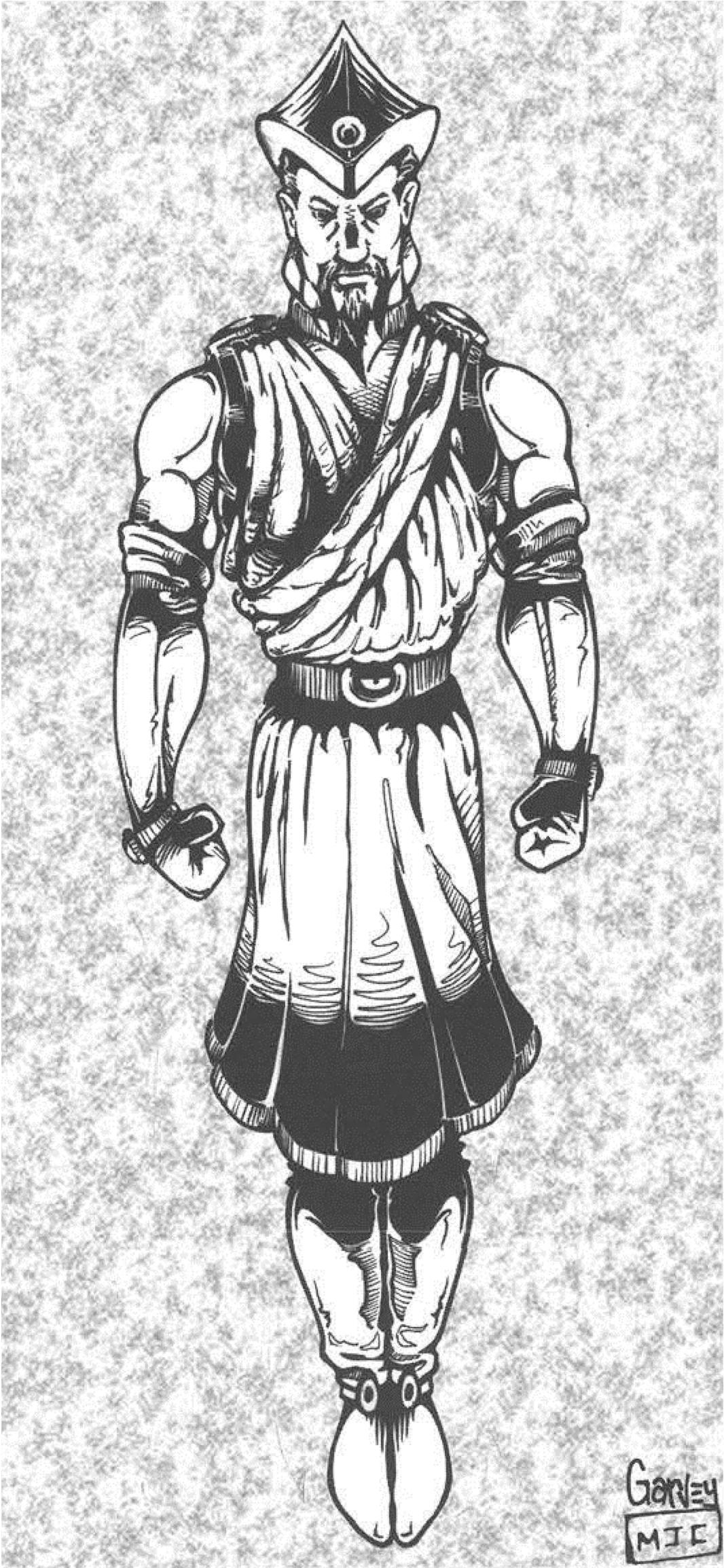

Let's see how Forge measures up to the first two; the third will have to wait until the next blog. The God-Wars The Forge rules open with a mythological treatise, explaining how the Supreme Being (named 'Enigwa') created the world and ordered it to be beautiful and harmonious. Enigwa then snoozes (having become Enigweary?) and his children, the gods, are left in possession of the paradise he has bequeathed them. The gods start off perfect too, but they become more differentiated as the ages pass, with some developing selfish or aggressive traits. The Supreme Being is disturbed by this discord and, I suppose, Enigwakes. He draws the gods together in fellowship to create Humanity and then commands the gods to be mankind's instructors and guardians, for Man shares the best and worst traits of the gods. Then Enigwa disappears, off to create new worlds (his Enigwork?), strangely blind to the trouble he has set in motion. The gods immediately fall out and a triumvirate forms: Necros the god of Death teams up with his brothers Grom the god of War and Galignen the god of Disease. Grom starts creating his own servitor races by mutating humans: the orc-like Higmoni, the Klingon-inspired Berserkers and the one-eyed gorilla Ghantu. After a polite pause to register their shock at this impiety, other gods follow suit: Dembria, goddess of Creation, creates the albino Dunnar; Katharu, god of nature, creates the lizardy Kithsara; Marda, goddess of Animals, creates the avian Merikii; Omara, goddess of harvests, creates the half-pint Sprites; even virtuous Berethenu, god of Justice, creates his loyal Dwarves. I'm not sure who creates the wheezing weasely Jher-em; Marda, I suppose. The Elves aren't attributed either, but Terestar the god of Time appeals to me as their creator. The gods go to war, tearing up the landscape. Marda is particularly wrathful, creating monsters and Dragons to defend her pristine wilderness. Necros figures out how to create the Undead to be his creatures. He tricks Dembria into creating the moon to blot out the sun, so that his undead army can dominate the lightless world. Then, when his sister Shalmar the goddess of Life pleads with him for peace, he murders her Enigwa returns to judge his creations and he isn't happy: his Humans have been mutated into other races, the landscape churned up and rearranged, Shalmar dead, the moon blocking out the sun: it's not pretty and the Supreme Being is Enigwrathful. He pronounces judgement on Necros, flinging the death-god into "the endless void." Grom gets dropped into the fiery depths of Mulkra for his crimes. Berethenu has the chance to repent but is too noble to accept forgiveness: he leaps into Mulkra to be imprisoned with Grom. Enigwa gathers together the remaining errant gods and takes them away with him, leaving the world of Juravia to recover from this divine ruckus. The various races are left to pick up the pieces in a god-free world. They reconstruct the principles of magic but, since these powers no longer come directly from gods, Pagan Magic is uncertain and has nasty side-effects. Down in Mulkra, Grom and Berethenu seize moments between burning in eternal agony to invest their worshipers - Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors - with Divine Magic. There are rumours that the gods occasionally sneak back to Juravia when Enigwa isn't Enigwatching and the monsters and undead horrors unleashed during the Great Wars are still out there, causing trouble. All this rationalises a fantasy world with monsters, races and magic, Dumb Names Guilty as charged, but it's not all bad. If Enigwa is a dumb name for the Supreme Being then chain me to the wall. It's got 'enigma' in it but the W has been flipped, see? The overall effect hints at something African, which is great. There are a lot of GFNs (Generic Fantasy Names), just syllables with -a or -ia or -ar added on the end. 'Necros' is lame, being filched from the Ancient Greek nekrós meaning 'corpse.' I'm sympathetic to the Tolkien Conceit, that fantasy names are just translations into familiar English of words that are really in other languages, so Peregrin Took was really "Razanur Tûk" in Westron. But if you're going to do that, be consistent. Shalamar should be named after the Greek for 'life' which is Zoe, Grom should be Polemos, Galignen should be Nosos and Marda should be Therion. Fine names all. Some of the names have a whiff of poetry to them. Galignen has connotations of 'malignant' which is clever. I like the -u names Berethenu and Kitharu, which suggest (to me) something Babylonian or perhaps Romanian or East Asian. Grom is a near-steal from Robert E Howard's Crom, the war-god Conan respects (I was going to say 'worships' but that's going a bit too far), and in turn adapted from Celtic myth. But it's all a mad jumble really and not in a good way. Over on Zenopus Archives, there's a 'Holmes Random Name Generator' that creates fantasy names extrapolated from the quirky imagination of Basic D&D author Eric Holmes. These names may be random but they're not GFNs: Chor Paldon, Zoque Kar, Losho the Blue, I could do this all day. Try it yourself: These names are random collections of syllables, but they're still evocative. Crucially, they're not European in flavour. They sound like they're from a slightly alien fantasy land: not Marda but Mardreb, not Dembria but Drebael. Thomas Wilburn slams Forge for (among other things) starting off with 10 pages of myth-making before we get a content page, never mind rules: "mythology belongs in a background section in the main text, not at the very front where the reader has to wade through it just to get to the game." But the trend for '90s RPGs to kick off with thematic fiction or campaign setting before introducing the rules was well-established long before Forge came along. No, I don't object to the positioning of mythology at the start of the book and it's well-written: in fact, it's the best-written part of the whole book. I just wish the Kibbe Brothers had knuckled their foreheads and come up with names that were genuinely evocative or thematically consistent . What cultural setting do these deities connote? Five minutes of Google-fu (or half an hour with a decent encyclopaedia) prompts suggestions like this: This harmonises the gods' names (I like that -u ending and -ara as the feminine suffix is more interesting than plain -a or prettified -ia) and Nergu re-names Necros along Babylonian lines. Just sticking an O- prefix in front of Grom works wonders (and connotes 'ogre'). Why would all the races use the same names? The creatures of Kitharu and Mardu get a synthesis of Babylonian and Yoruba names and the 'Grom-folk' (Higmoni, Berserkers, Ghantu) get Japanese-inspired adaptations. I think the Dunnar would have Celtic-style names (reverencing Dembara and Dobuna, Berethenu as Berethos and Grom as Crom) and let's go with Norse-style for the Dwarves (re-titling Berethenu as Borothor and Grom as Grotun) and Greek-style for the Elves (Berektor and Grotos). Names do amazing things: they imply a world. Un-fun Strictures No surprises here. Grom Warriors and Berethenu Knights both have to follow an honour code. For Grom-ites it's a simple barbaric code of never running away, fighting face-to-face and taking part in a demented yearly rally. Berethenudians have a chivalrous equivalent that gets more restrictive as they advance: eschewing armour and fighting fairly. From a roleplaying perspective, these strictures are intensely external to your character's identity. It's frustrating for Berethenu Knights that they cannot wear plate mail and have to give away a tithe. Not being able to attack from behind makes a few combat encounters slightly more awkward than they have to be. But you can 'tick the boxes' with these requirements and play your cleric just like all the other characters. What we don't learn is what foods are forbidden, what clothing must be worn, what sex acts are condemned, what daily rituals must be enacted. In other words, what is like to live in the service of this god?