|

The Coney-Cliff Crypt is a 30-minute Dungeon Challenge, as set out by Tristan Tanner in his Bogeyman Blog. It was submitted by Karl McMichael who wins a copy of Forge Out Of Chaos as his prize in the January 2020 competition. Thanks to Andrew Cook for the stylish cover Karl submitted the dungeon with references to D&D 5e; I've added a few conversions to Holmes/BX/AD&D and I'll adapt the whole scenario to Forge Out of Chaos next month. Andrew Cook has created a printable version of the scenario. I've adapted (and slightly expanded) the scenario for Forge Out of Chaos.

BackgroundA Necromancer has enslaved a tribe of Kobolds, insisting he can raise the skeleton of a dragon with human bones and sacrificial ritual. To this end, the Kobolds have been luring local villagers into nefarious traps then turning them over to the Necromancer. An adventurous gang of local teens have entered the dungeon and (mostly) been killed or captured. The Hook Disappearances have been occurring around the old crypt on Coney Cliff: recently five teenagers from the village went out to investigate but never returned. They are Devonna (gentlewoman), Tad (woodsman), Nedward (scribe), Hedrick (militiaman) and Genelle (rogue). The mayor fears something eldritch and ineffable may be going on. You have been sent to retrieve the disappeared youngsters or bring back their bodies. Rumours (1d8)

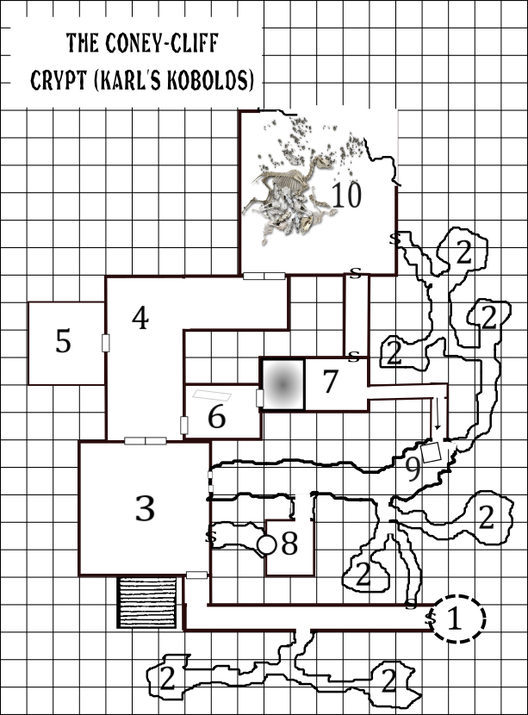

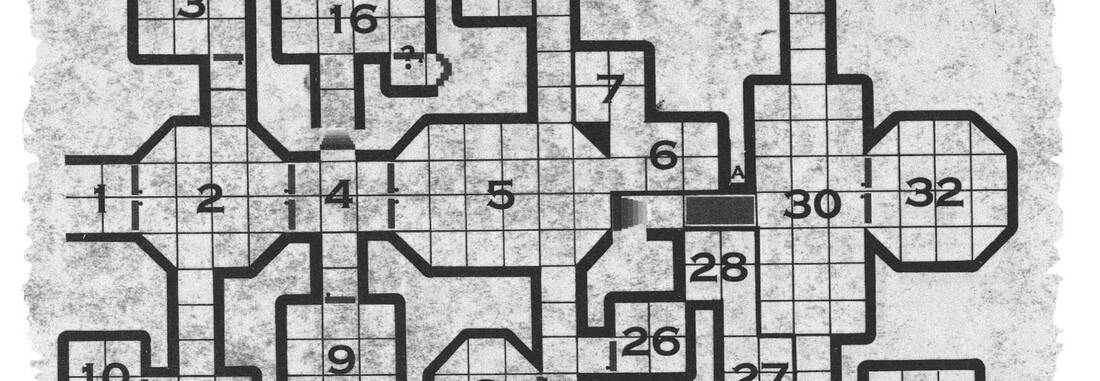

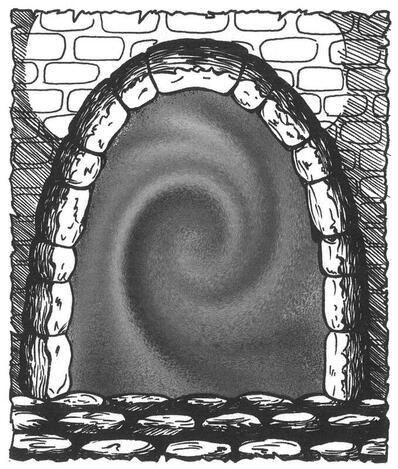

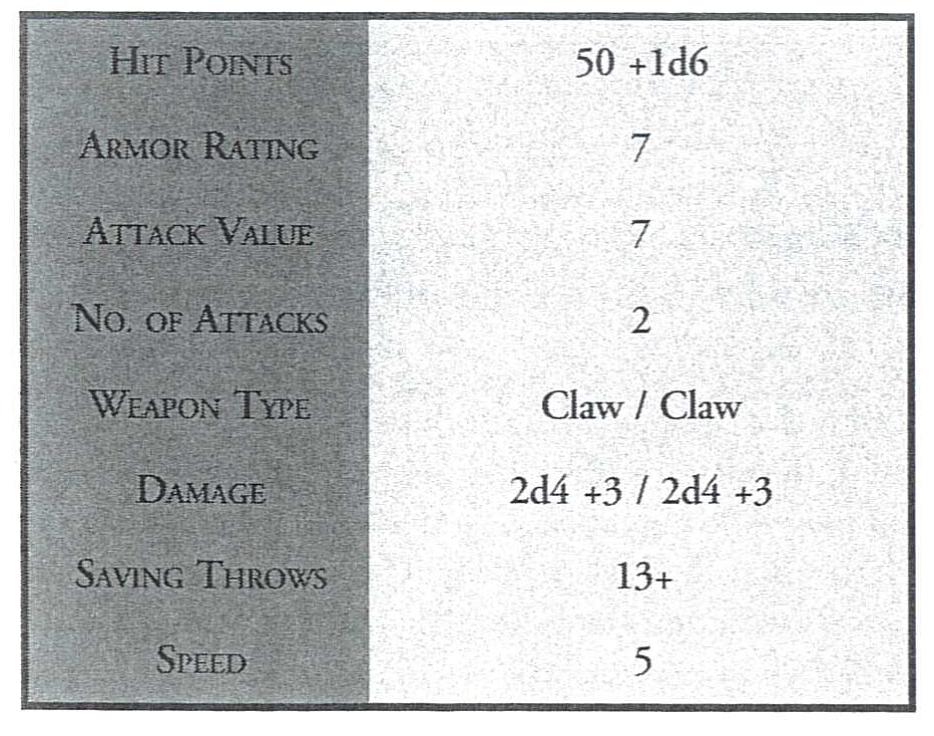

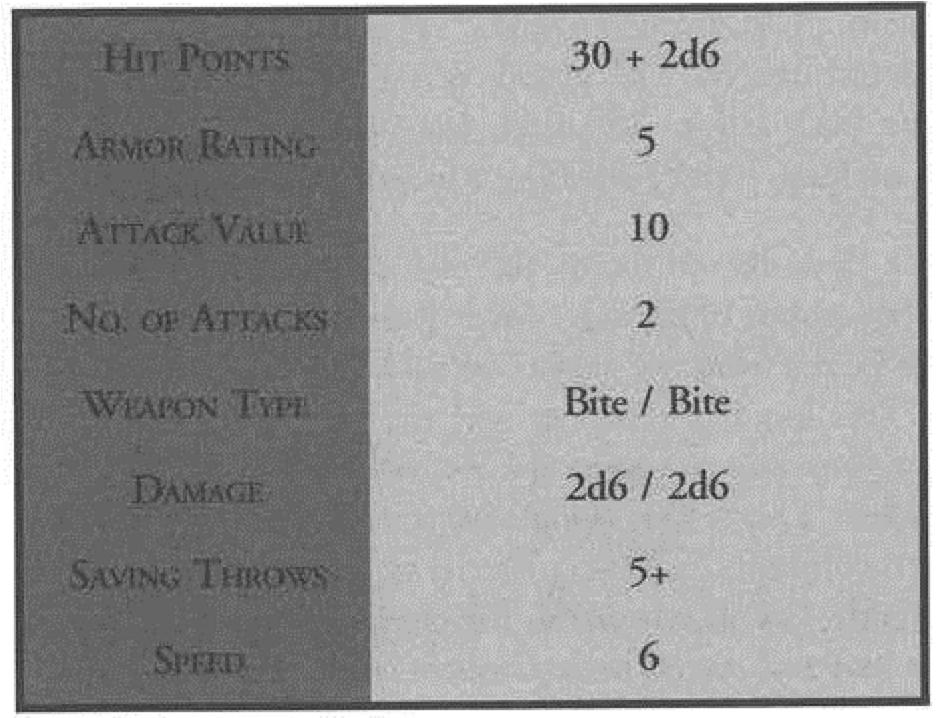

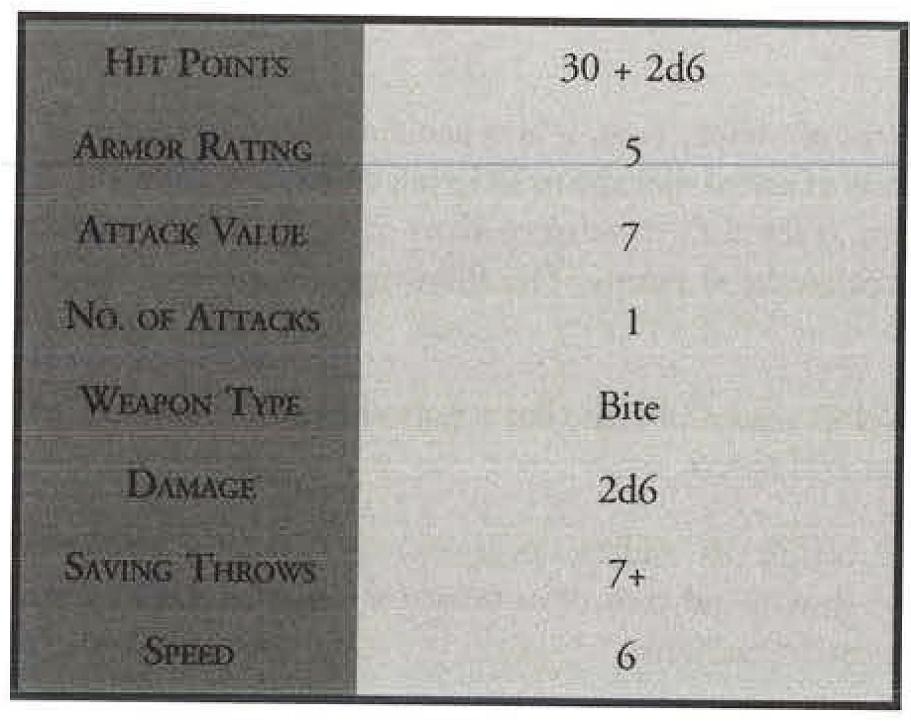

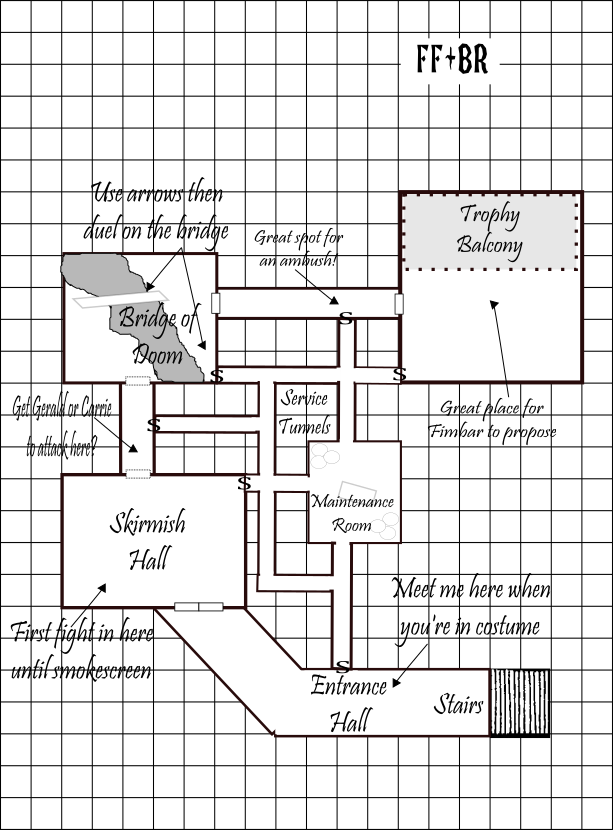

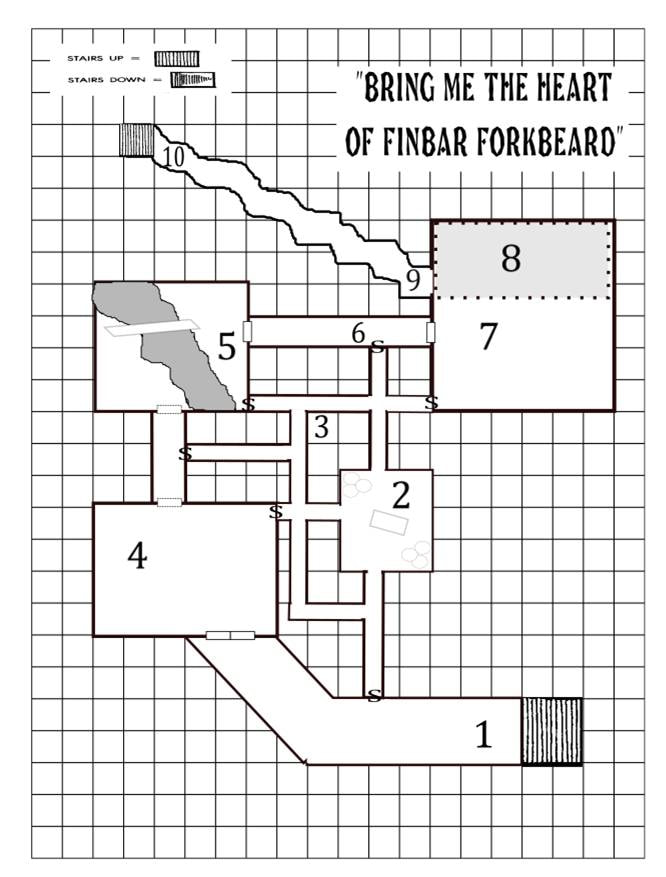

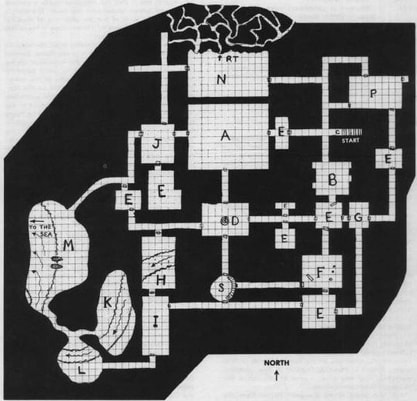

Coney Cliff is a windy rise well above the sea. As the wind howls in from the sea, faint cries and wails can indeed be heard on the wind. A tumbledown dry stone wall surrounds weather-beaten grave stones and tombs. A grand-looking crypt entrance stands most prominent: it is ornately carved with rusted iron gates open leading downward. However, the stone doors a few steps down but are stuck fast. Inscribed above the entrance reads: ‘Honour, oath and promise, here lay my briar brothers.' Dotted around the ground are dozens of rabbit burrows, several of which upon closer inspection contain jewellery, coins or semi-precious baubles (these are traps: see area 2). To the east of the Crypt Entrance lies a well (1); if the party look down inside they will see the flickering of a torch and hear a voice from below asking for help. Each square is 5 feet 1. The Well The Well has only 2' of rope attached to the winch. It descends 30' into water that is 5' deep. Five feet above the water, several bricks have been removed (a secret door) and the area around the bottom of the well has been roughly excavated; some buckets and broken tools lie strewn about. There is a young man trapped down here with a dying torch; Nedward is thankful somebody arrived to help him as the rope he climbed down on snapped. He will tell the PCs a confusing tale of how he came here with his four friends: “Genelle disappeared before we came down. We tried the crypt door but it’s stuck fast, so we came down here when we saw the light. We went down the corridor beyond those bricks, but there was this shrieking thing! Lucky Devonna brought a sword and Tad borrowed a wood axe. They chopped it all up, my ears are still ringing though. They went through the door but there was a skeleton! Hedrick and I ran to get help, but when I got back Hedrick was gone! I’m no warrior, and I’m not brave. I guess dad was right, I’m only good for running and reading.” Nedward will attempt to leave, but might be persuaded to help if PCs leverage his insecurity about his father. He is a 3HP normal human with no armour or weapon but carries 5 torches and a tinder box. At area 4, he might give them a clue for the door: “It wants your word, some sort of promise.” Along the corridor is a secret door leading to a tight passage (where Hedrick was abducted); if it is discovered the Kobolds beyond will retreat to room 10. At the end of the corridor is a shoddy door, badly hung. In front of the door is a giant purple fungus, hacked apart by Nedward’s friends. 2. The Rabbit-holes/Kobold traps These small caves are linked by tight corridors. Creatures taller than Dwarves fight at -2 in the tunnels; those larger than Kobolds or Gnomes must travel and fight single file and cannot use shields; no one can use two-handed weapons. Kobolds can fight two abreast in the tunnels. In each of the numbered locations are 2 Kobolds, 14 in total (MM pg.195, 1 spear armed, 1 with javelin and club). They act as teams to capture those who reach for the trinkets in the rabbit holes at dawn and dusk. For Holmes/BX/AD&D, each Kobold has 2HP and deals 1d4 damage. Each hole has a snare that one Kobold tightens round the victim’s wrist as they reach in. They pull together to drag the victim into the crypt. They will bash the victim repeatedly until compliant or unconscious and bind them in room 10. If this fails, the spearman will finish the job and drag the body to room 10. Each group of Kobolds reacts intelligently: follow and ambush intruders, seek other Kobolds to gang up, attack intruders immediately, play dead, fake calls for help, self preserve and stay still or surrender and lure the PCs into a trap (e.g. room 5). Their motivation is to protect or misdirect intruders away from room 10. 3. Tribute Room (15' high) The room is covered in murals (a good amount may be covered by soot) which depict heroic deeds and figures in full plate with bramble motifs battling demons and defeating a giant dragon. There is a staircase that would lead up to the Crypt Entrance but the ceiling has collapsed, making it impassible. On the east wall, several bricks have been removed and bare soil is clearly visible: this is the secret door to area 8. The door in the North wall is carved with the same phrase in multiple languages: ‘I strive to keep order, to fight chaos and uphold the integrity of the Briar Knights.’ There are 2 skeletons (MM pg. 272) in this room which will rush to close the door in the south wall if they can and attack if not. For Holmes/BX/AD&D, each Skeleton has 4HP and deals 1d6 damage. In the centre of the room is a 5' wide copper bowl full of pitch. There are two arrow slits are located 12' above the floor on the east wall. Two Kobolds fire at any who enter room 3 with light crossbows for 3 rounds (targeting the least armoured character, including the boy Nedward from area 1). During the second round of combat, a Kobold from the arrow slit will fire a burning brand into the copper bowl igniting it and causing the room to fill with thick black smoke: 1’ after 1 round, 3’ after 2, 5’ after 3, 6’ after 4, 10’ after 6' and after 9 rounds the room will have 14' of smoke (it will stay at 10' if any doors are open) and the fire will die out. 4. Hallway of Oath There is a door to the east (room 5) which reads: ‘Here we lie.’ Daubed across it in thick red paint is a draconic script which reads: ‘CORPSE STORE. DANGER.’ NOTE: A Kobold group stalking the party may wish to open room 5 and unleash the Zombies if the PCs are looking too healthy. The door to the east (room 6) reads ‘ Here we are remembered.’ As the players proceed along the hall, they hear a female voice: ‘I am to join you Tad, they've come to finish me off.' Around the corner are two figures: a young man slumped against the wall, a woman hunched clutching her thigh with one hand and brandishing a sword with the other. The dead figure is Tad, a quarrel is protruding from his chest. The young woman is Devonna. A dead Kobold lies at her feet. She is in poor shape and laments her foolishness. She will do what the party asks of her but is in no shape to fight. The door to the north is heavily carved and inlaid with silver. It depicts a figure in plate armour with an ornate helmet crowned wìth thorns. It has a banner across both doors. It reads: ‘If you are to keep this, you must first give it to me.' The answer is oath/word; the specific oath is carved all over the door in room 3 in multiple languages and the correct response is: ‘I strive to keep order, to fight chaos and uphold the integrity of the Briar Knights.’ Upon receiving the correct answer, the door will open. The door may be picked, but unless the lockpicker criticals (or succeeds on two successive rolls for Holmes/BX/AD&D), a tiny hammer will fall on the lockpick, breaking it before resetting the lock in the door. 5. Zombie Room A room with open and smashed sarcophagi. The room is packed with 8 zombies (MM pg. 316). For Holmes/BX/AD&D, each Zombie has 8HP and deals 1d6 damage. Unless the door is closed quickly, the Zombies will spill into the corridor and attack anyone they come across. The zombies are Briar Knights raised by the Necromancer and instructed to attack intruders in preference to Kobolds. 6. Timber Room This room contains nothing apart from wormwood ridden timbers. Two are long enough to cross the pit in room 7 but one (50% chance it is the one the PCs use) is rotten and will break if any creature heavier than a Halfling walks across. A door leads east. It is of poor quality and fitting but it is locked. The lock is not a difficult check, but using force to break it down results in momentum carrying the PCs into the pit in room 7. 7. Spiked Pit A spike pit covers the west side of the room; there is a 10' drop into spikes covered in excrement and urine (DMG pg. 123). This is also a toilet as well as a trap. For Holmes/BX/AD&D, falling into the pit deals 1d6 damage and the character must Save vs Poison or take 1d4 damage and contract a disease (similar to Giant Rats). NOTE: this could be a great place to ambush PCs with one or more Kobold groups. There is a secret door to room 10 on the north wall. A tight slope leads up to room 9, climbing 10' (PHB pg. 192). If the Kobolds in area 8/9 are still active, the PCs will hear cries of help from room 9 (this is a trap). 8. Secret Ladder Entry The corridor terminates in a ladder which scales 10' up into room 9. If PCs find the secret door and enter here, the 2 Kobolds firing through into room 3 will come here to attack when a PC is at the bottom of the ladder. One will douse the intruder with a bucket of oil, the second will throw a burning brand down after it, setting the oil on fire. Once a PC reaches the top of the ladder, the Kobolds will do the bucket trick again on anyone else climbing up. The Kobolds will then summon two of the groups near them to join the fight and send the third to room 10. 9. Kobold Barracks (9' high) The earthen tunnel is full of rags, clothes, miscellaneous bones, boots and whatever the Kobolds took from commoners. On a crude dais in an alcove is an articulated wooden dragon toy surrounded by gems and gold coins. Leaned against it is a +1 magic warhammer with etched brambles along the head, a wand of magic missiles with 1d12 charges and 2 healing potions are also nestled in the pile. If players entered through area 8, there will be no fight. There is a caged mastiff by the slope to area 7. It is starved, blood thirsty and rages wildly when it sees the PCs. If the players enter through area 7 (perhaps answering the fake ‘cries for help’), the 2 Kobolds keeping watch on room 3/8 will drag the caged mastiff (MM pg. 332) over to the slope and lift the door of the crate to release the brute. They will then do the same as in area 8, using only 1 oil bucket to send a pool of burning oil down the slope. For Holmes/BX/AD&D, the Mastiff is HD 2, 8HP, AC 7, bite for 1d4+1. A young woman is bound tightly in the corner by the cage; her name is Genelle. She cries for help and to be cut free. She explains how she saw some fairy gold in a rabbit hole and was pulled underground, beaten and tied. Genelle is a 1st level Rogue/Thief (HP 3) and knows the route to room 10 through the Kobold tunnels and the secret door: she was taken there by the Kobolds and witnessed Hedrick being murdered but the Necromancer sent her back to the barracks to ‘amuse’ his servants. Genelle will agree to aid the party but will run away as soon as the Undead Dragon animates. 10. Necromancer's Lair & Dragon Grave The party disturb the Necromancer (and any Kobolds that fled to the room). There is a gaping 20' wide scar carved through the cliff face; it looks out over a tumultuous sea. Wind whips in through the hole, billowing the robes of a dark figure. There is a large skeletal dragon stretched upon a mountain of treasure. The ancient bones and mound of treasure is stained with strange patterns and sigils in deep red. The metallic smell in the air is overpowering as well as the stench of decay. Piled inside the rib cage of the dragon are corpses in varying degrees of decomposition; one is very fresh (this is Hedrick, one of the missing teenagers). Along the West wall is a lean-to with a bed roll surrounded by books and scrolls. A fire rages in the centre of the room. The Necromancer slashes his hand and places it on the forehead of the great skeletal beast. He says: ‘You called me mad.’ The dragon begins to shudder, limbs snapping magnetically into place. ‘Untalented.’ The dragon pulls itself upright on its forelegs ‘But I’ve done what you never could’ The dragon shoots forward on forelimbs; it is lame, dragging the back legs and pelvis uselessly. The Necromancer slumps exhausted, enamoured with his creation. He ignores the PCs. He will not interact or react to the PCs and will mutter and mumble to himself regardless of outcome. The Dragon’s stats are noted below. The treasure is left to the DM’s imagination. Frail Skeletal Dragon (5e) Large undead, lawful evil AC 15, HP 65, Speed 20' Str 16 (+3), Dex 8 (-1), Con 16 (+3), Int 8 (-1), Wis 10(0), Cha 10 (0) Saving throws : Dex +2, Wis +3 Languages: Draconic; Skills: perception +2 Damage vulnerability: bludgeoning; Damage resistance: neurotic; Damage immunity: poison; Condition immunity: poison, exhaustion Senses: blindsight 10', darkvision 60', passive perception 12 ABILITIES Noxious odour. Any creature within 5’ must make a DC 12 Con saving throw. On a failed save the creature is poisoned for the next minute. A creature poisoned in this way can repeat the saving throw at the end of its turn. ACTIONS Multiattack. This creature may make 2 attacks per round. Bite/breath weapon and claw. Bite. Melee attack. +4 to hit. 5' reach. Single target. (1D10 +3) piercing. Claw. Melee attack. +4 to hit. 5' reach. Single target. (2D4+3) slashing. Breath weapon (recharge 5-6) bone shards: 15’ cone. DC12 Dex saving throw. 5D6 damage on a failed save or half as much on a success. Skeletal Dragon (Holmes/BX/AD&D) AC 4, HD 5, HP 25, 2 claws & bite for 1d3/1d3/2d6, bone shards breath weapon in a line to 40', cannot be subdued but may be turned as a Spectre, treat as undead, nauseating odour the same as Troglodytes Commentary Karl has invited me to write a commentary on his scenario, which I'm delighted to do. Karl took his inspiration for this from Tucker's Kobolds. Back in 1987, Roger E. Moore wrote a famous editorial for Dragon #127 in which he described a dungeon adventure where a tribe of kobolds (the weakest of the D&D humanoid monsters) were deployed so cleverly they posed a significant challenge for even high level (6th-12th) adventurers. "Sometimes," Moore concludes, "it's the little things—used well—that count." Karl places his 16 Kobolds where they might capture some incurious PCs immediately, by dragging them through fake rabbit holes into underground caves and knocking them unconscious. Once the fight moves into the dungeon, the Kobolds take advantage of cramped, low tunnels where they can gang up on their restricted opponents. The Kobolds make use of traps and advantageous positions to pepper the PCs with arrows, pour burning oil on them, unleash savage dogs on them and retreat from direct melee wherever possible. The PCs will be badly battered and probably will have lost party members when they arrive at the climactic showdown with the undead dragon, a fight which will finish them off unless they make use of surprise or are sensible enough to flee. This is a delightfully malevolent dungeon, designed to give the PCs terrible experiences at every turn. 1st level characters probably won't get very far at all: 2nd level characters might be hardy enough to live to run away at the end. Set against this punishing experience are two mutually-reinforcing themes. One is the Crypt's original function, as the resting place of a noble order of nature-themed paladins. There are touches of beauty down here, in the bramble-motifs in the Tribute Room, in the dignified oaths and high-minded solution to the riddle on the doors. This was not always a terrible place, but it has been despoiled and corrupted. The PCs should be inspired to salvage what goodness and hope can be found down here, which leads to the second theme... The other theme is the rescue of the five teenage wannabe heroes. These characters are like the cast of a Hollywood horror movie who stumbled into a Very Bad Place: Hedrick and Tad are now dead, but the PCs can rescue Nedward, Genelle and Devonna and need to remember that this is in fact their mission. If they can bring all three youngsters alive out of the dungeon, they should feel rightly proud of themselves. Confronting the Dragon is pure hubris. If you referee this scenario, you might feel differently and want the PCs to have a fighting chance against the Dragon. You could rule that, if the Necromancer is assassinated, the skeletal dragon-thing collapses in ruins. More interesting is to emphasise its weakness: it has no mobility and cannot turn around, so PCs attacking from behind should enjoy Thief-like backstabbing advantages and Thieves themselves should inflict even more damage (triple, if you use Holmes/BX/AD&D). This heroic ending rather detracts from Karl's dramatic intention, but some player-groups prefer to win like heroic fools rather than flee and live like wise tacticians.

2 Comments

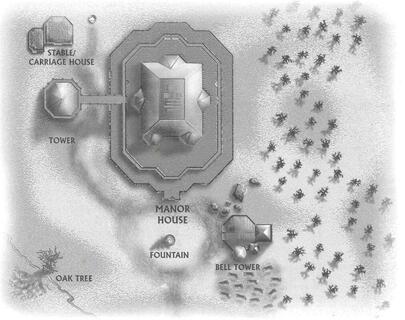

Tales That Dead Men Tell (hereafter, Tales) is the second and final scenario published for Forge Out Of Chaos by Mark Kibbe back in 1999. It retailed back then for $9.95 and consists of a 46-page staple-bound book with colour cover art (by Jim Feld) and some B&W interior art (also by Feld, a departure from the team who worked on the original rulebook), including regional and local maps by Steve Genzano and lots of illustrations of NPCs and enemies discovered during the scenario. Tales isn't available as a PDF through DrivethruRPG but there are a lot of copies for sale online, from as cheap as $3 from some book sites to a typical $6 on eBay. First glance shows Tales to be a more ambitious project than The Vemora (1998). Gone is the cartoony artwork of Mike Connelly and Don Garvey: Feld's moody and murky illustrations set a more crepuscular tone that fits the spooky theme. It's a more mature and professional style and it definitely gives reptilian Kithsara and bestial Higmoni a much more distinctive look. Jim Feld (left two) compared to Higmoni and Kithsara by Connelly/Garvey Connelly and Garvey homaged 1980s D&D with their style, but Feld is a step onwards and upwards, offering Forge its own visual identity - yet I can't help feeling that something charming has been left behind. In fact, much has been left behind, as we shall see. Background And there's a lot of this. Whereas The Vemora was set in a rather hazy fantasy kingdom with a distant High King and a local Village Elder, Tales is rooted in the detailed history of the Kingdom of Hamsburg, which seems to be pitched to us as Forge's default setting. I'll have more to say about Hamsburg and the Province of Lyvanna later on. Suffice to say, this is a territory that has won its independence from being an imperial colony and is the sort of trade-hungry border region that fantasy RPGs seem to gravitate towards. More relevant is the recent history of thief-made-good Kamon and his ambitious wife Maria, a woman combining the more extreme traits of Cersei Lannister and Scarface. While Kamon works like a dog building up a mercantile business, Maria constructs a criminal empire under the cover of his honest dealings, offering Kamon Manor out as a safe house to the Rat's Nest, a nasty band of villains. When the Law comes calling, poor old Kamon is executed, one of Maria's sons is killed and Maria goes to gaol, leaving her youngest son to expire all alone, locked in the cellar. The Manor is subsequently haunted by the ghost of Maria's betrayed husband and her abandoned son. That was all a generation ago, but now a team of Necromancers has arrived at the Manor with some mercenary Higmoni (it's always the Higmoni...) in tow. They've suppressed the hauntings by ringing a mystic bell and ambushed the local militia sent to investigate the strange goings-on. They're looking for Kamon's fabled treasure, hidden somewhere in the house. The Hook The PCs are the usual swords-for-hire and are recruited by an elderly merchant who rejoices in the astonishing name of Aberdeen Jenkins. Jenkins has bought the Kamon Manor estate as a fixer-upper but needs the adventurers to sort out the mystery of missing militiamen, ghostly bell-ringing and sundry hauntings. Simple as that, really. Do some research in Lyvanna into the Manor's history then get down there and clean the place out of troublemakers. Jenkins is paying 500gp for this bailiff-work and - weirdly - is prepared to let the adventurers keep any treasure they find on his estate while they do it. That's a bit mad, but I'll suggest a more rational offer for Jenkins to make later on. Research in Lyvanna As well as a simple 'rumours' table, Tales invites you to explore the town of Lyvanna and interview a selection of NPCs about Kamon Manor and its unlucky history. This research phase gives the scenario a bit of a Call of Cthulhu vibe, although it sits somewhat oddly with Forge's system, which doesn't offer players any social or research skills. Ron Edwards (2002) summed up Forge as a game that was "gleefully honest about looting and murdering as a way of life, or rather, role-playing." I think he exaggerated, but Tales' shift away from dungeon-bashing towards investigation and negotiation is a clear departure from the ideas that were noticeable in the rulebook. Whether Forge's mechanics really support this style of gaming is another matter... Roaming around Lyvanna, the players can interview the helpful Dunnar sage Xavier Pratt, the helpful local lord Bromo Lionheart, the helpful militia leader Captain Honis, yes, everyone in Lyvanna is very helpful. Now don't get me wrong, I don't like grimdark settings where everyone is backstabbing everyone else, but these NPCs are intensely static: the designers give each one a distinctive behavioural quirk, but none of them has an agenda or a subplot to offer. They're just waiting for the PCs to turn up so they can deliver their exposition. Perhaps sensing that their setting lacks dramatic conflict, the designers present a pickpocket and a conman for players to interact with and some agents of the Rats Nest who will start dogging the PCs' footsteps. More about them later. Off to the Kamon Estate Once on the grounds of Kamon Manor, the PCs can wander freely by day or be harassed by Giant Bats at night. If they take cover in the Bell Tower and kill or chase away the Higmoni guard, there will be consequences: with no one ringing the bell, the ghosts of Kamon and his son resume haunting the site. Superior maps and tone-setting art, compared to The Vemora from the previous year The Manor House is an old fortress and entering it will tax the players' ingenuity. The front gate is guarded by more Higmoni but the walls can be scaled and the side tower accessed through a bridge. There's a prisoner to rescue in there (an unlucky Rats Nest spy) and a dangerous monster, a Vohl (which is a sort of taloned ghoul, as opposed to a vole, which is a cute water rat). Exploring the house is a tense affair, especially if Kamon's ghost is active, whispering creepy things, pushing people down stairs and dropping statuary on passers-by. There's a chipper Sprite adventurer also moving through the house: Theo Bratwater will join the party and be either useful or annoying, depending on how the Referee plays him. There's a militia man to rescue, two Necromancers to tangle with, plenty of Undead and the Higmoni captain who might leave without a fight if approached correctly. There's also the ghost of Davis, Kamon's tragic son, who appears to be a normal kid and a helpful guide until you stumble across his corpse in the cellar. The main bosses are the Necromancers: Chiassi the reptilian Kithsara and Berria the Elf. These two are presented with spell lists in full and demonstrate the crunchiness of the Forge system, offering the Referee plenty of choice, both in roleplaying their reactions and selecting their most effective tactical responses. Chiassi: check out his feet! Hopefully, the players discover the documents exonerating Kamon and lay his ghost to rest. On the way home, those three Rats Nest spies (remember them?) ambush the exhausted party, prompting a final act battle. Evaluation: non-Forge As I've discussed elsewhere, Forge converts painlessly to older iterations of D&D and even 5th ed conversions shouldn't pain anyone too much. The Higmoni are Orcs or Half-Orcs, the Necromancers are Chaotic/Evil Clerics, Zombies and Skeletons are Zombies and Skeletons, the Ghosts don't require stat blocks and the other dangerous animals or carnivorous plants have easy-to-source analogues in various Monster Manuals. The Vohl would be 7HD, AC 4, 3 attacks for 1d6/1d6/1d2 (Save vs Death Ray or lose those 1d2 HP permanently), MV 15" or 150' (50') - a nasty opponent for low-level characters. It's a tougher scenario than The Vemora in terms of the number of monsters and the spell-casters: probably better if most or all of the PCs are 2nd level rather than 1st, maybe with a 3rd level Thief on board. But that, I suppose, makes it a good follow-up to the earlier dungeon. Do you need it, though? The Vemora was a fantastic tutorial dungeon with enough dangling plot threads to prompt me to write an expanded version of it. Tales feels less essential. On the positive side, it's an intelligent explore/destroy mission and Mark Kibbe has a talent for dungeon layouts that generate drama. The presence of the tragic ghosts lends an element of spine-tingling mystery to things. The maps, NPC portraits and caption boxes are all attractive: if the whacky or primitive art of the earlier books repelled you, you will feel you're in the hands of professionals now. On the other hand, the stakes are quite low. You're bailiffs for Aberdeen Jenkins (that name!!! I'm in love!), turfing out trespassers on his land. It's not glamorous. It reminds me of the sort of thoughtful scenario White Dwarf used to publish in the UK in the 1980s - or the AD&D module U1: The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh (1981); the one that sent the PCs to a haunted house that was really a cover for smugglers. The "Scooby Doo episode of D&D modules" according to Ken Denmead (2007) vs the 1986 WFRPG Or, perhaps, a better fit is Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, with its dark fantasy-Europe setting: any story in which a wealthy merchant sends you up against evil cultists and a vicious guild of thieves has a clear WFRP vibe going on. WFRP delights in its low-fantasy theme, its dark low-key dramas and tragic backstories. But of course U1 shifts its action from searching the old Alchemist's House to raiding the ship Sea Ghost, whereas Tales doesn't really go anywhere: you don't get to track down the Rats Nest and punish them for their perfidy. The space in the booklet is taken up instead with fluff about Hamsburg and Lyvanna, which I don't think most DMs will be making use of. So let's talk about the setting. Sensible Settings, Yawn... The cover of The Vemora surprised me with its Tudor buildings, lacy collars and breeches. Tales shows that the 17th century tone was quite intentional. This is not a Dark Ages or even Medieval world. It's Renaissance or perhaps Baroque. The various kingdoms and empires are stable, with parliaments and universities. Government exists "to uphold the welfare of the commoners" (p10), which is as clear a statement of Humanism as you could wish for. The focus is on tariffs and taxes, laws against "unfair trade practices and economic collusion" and revolts that remove oppressors from power. In other words, far from being dystopian, Hamsburg seems like a lovely place. You cannot imagine giant flightless birds, enormous man-eating beetles or two-headed super-snakes marauding across this landscape. Maybe a dandy highwayman inconveniences travelers, but never a dragon. It's the sort of setting that makes Tolkien's Shire look gritty and morally ambivalent; the politics are more cut-throat in Narnia! Mark Kibbe offers one concession to cultural darkness, which is the Hamsburg seems to treat women poorly. Kamon's wife Maria barters herself into marriage and criminal dealings in pursuit of power and autonomy in a world the treats her sex as chattel. The problem is that Kibbe's imagination is so genial that he forgets his world is supposed to be like this: we are told Maria's teenage daughter survives the fall of her family because she was off at University at the time. How very progressive! Look, I don't mind idealised fantasy settings, but there seems little point in describing their political settlements if there are no important conflicts going on. Conflicts don't have to explore the dark side of human nature: some people are greedy, fanatical, jealous, cowardly or filled with hate; others are generous, idealistic or desperately in love. Nobody in Lyvanna seems to be doing anything, good or bad, except the Necromancers, and they're just cartoonishly evil. Evaluation: Forge The positive is that Tales is a step forward for Forge in many ways: in production values, story complexity, world-building and so on. The downside is that not all of these steps develop what was noteworthy and interesting about Forge in the first place. The original Forge rulebook boasted a hell-on-earth setting, ruined by the gods with mortal races left behind to survive in a dystopian world. The monster Bestiary resembled Gamma World's collection of mutants and horrors more than a conventional fantasy monster manual. The PC races were exotic and rather primitive. The rules embraced dungeon delving and tactical combat, with few skills or spells for politicking, negotiating or carrying out deceptions. Tales takes place in a harmonious and rather advanced world that resembles (to my mind) the New World colonies in the 17th century and the cosier parts of Reformation Europe, far away from the 30 Years War or the Witch Trials. Everybody seems to be human, with a few Elves, Dunnar and Kithsara as 'exotics'. One cannot imagine giant one-eyed gorillas or telepathic weasel-people moving through this society. The naming conventions reveal much. In The Vemora, NPCs have names like Kharl Atwater, Brundle Jove, and Jacca Brone. The High King's name was Higmar. Solid fantasy names with a touch of otherworldliness to them. In Tales, we meet Maria Yates, Xavier Pratt and the incomparable Aberdeen Jenkins. These aren't bad names either, but they're very different names. They belong in our world, albeit to colourful people. The God-Wars have faded from the imagination and religion is back. Maria marries the hapless Kamon in "a small roadside church," the Province of Lyvanna is governed by "wealthy landowners and influential clergymen" and the local temple of Omara is "very small compared to the elaborate churches of larger towns" - in other words, this is Christian Europe, thinly disguised. Clearly, Mark Kibbe has matured and his imagination has moved away from the barbarian world of Forge towards a more sophisticated setting. That's fine. The problem is that Forge doesn't really support roleplaying in such a low-fantasy world. There are no illusion spells or skills for things like pickpocketing, faking signatures or seduction. Plus, your character is a giant one-eyed gorilla! Final Reflections There's a solid scenario here. It would be great adapted for WFRP but D&D players would enjoy it as part of the Saltmarsh campaign. The scenario creates a problem for itself that the passions and betrayals of Maria and Kamon's marriage and their gruesome ends are far more interesting than the events going on in the present. How much better the story would have been if the PCs were contemporaries of Maria: they could be employed by her to get her treasure back (only to be betrayed by her in turn when she strikes a deal with the Rats Nest), rather than acting as bailiffs for the soft-hearted Aberdeen Jenkins, decades later. In other ways, the scenario inspires fresh directions. In an earlier blog post I introduced the idea of Dungeon Constables or 'Dinglemen'. In this adventure, the PCs are themselves the Dinglemen, sent by the owner to evict trespassers from his 'dungeon'. The idea that the PCs keep the treasure they find there is absurd: it all belongs to Jenkins by right and the PCs are paid a wage to retrieve it. This introduces nefarious possibilities if the Rats Nest approach the PCs to fake an 'ambush' whereby the treasure is all 'stolen'; the PCs and the Thieves can later meet up secretly to divide it between them. Do the players take the deal and betray their employer Jenkins? What happens when the Thieves betray them and keep all the loot for themselves? The module's back page advertises an intriguing third module: Hate Springs Eternal, "coming in November 1999." This scenario sounds thoroughly epic, with an arch-mage returning from the dead and the PCs battling through an army to save the continent. A new type of Magic is promised! Alas, it was not to be. Tales turned out to be the second and last Forge module, leaving the game with a distinct identity crisis that is only deepened by the directions taken in the World of Juravia Sourcebook (2000), which I'll look at next.

After reviewing Mark Kibbe's 1998 module, I set about expanding it in order to develop its dangling plot threads: what was the truth behind the deadly plague that brought down Thornburg Keep and resisted even the healing powers of the Vemora? what is Shirek the Ghantu doing in the Keep and what are his humanoid minions searching for? what happened to the Cavasha? how does all this fit into the Kibbes' mythology of banished gods? The expansion document is found on the SCENARIOS page. Paul Butler's lovely cover illustration of the Cavasha: alas, the scale of the houses is all wrong The Return of Galignen The Forge rulebook introduces Galignen as the god of Disease, but also of nasty plants (fungus, molds, slimes, etc). He's the younger brother of Necros (Death) and Grom (War) and joined their Triumvirate that tried to take over the world during the God-Wars. He is "deceitful and unscrupulous" and "despises mankind" which he looks upon as "insects" and he "twisted man into sentient flora." During the God-Wars he "unleashed pestilence and plagues, the most severe of which was known as the Rotting Death." Artist Mike Connelly's depiction of Galignen The rules list Galignen among 'Those Taken from Juravia' as opposed to Necros (cast into the Void) and Grom and Berethenu (banished to Mulkra/Hell). Why did Galignen get off so lightly, since he seems just as malevolent as Necros and as destructive as Grom? An idea for a Forge campaign could focus on Galignen: what if he escaped creator-god Enigwa's wrath and judgement by merging himself with Juravia's plantlife? For hundreds of years, Galignen has been present in Juravia, assumed to be banished but really just left behind. He has spent that time slowly recovering his sentience and a bare fraction of his divine power, perhaps inhabiting a giant fungus colony in a deep cavern, attended by a loyal cult. The secret of the Vemora There is more than one Vemora. The Vemoras are relics left behind by Enigwa in his wisdom to counteract the power of Galignen, should he have survived the God-Wars. The Vemoras' healing properties are side-effects of their true purpose: they are the spiritual locks that prevent Galignen returning in power. In order to regain his full divinity, Galignen needs to corrupt or destroy all of the Vemoras. The attack on Thornburg Keep's Vemora is just one manoeuvre in Galignan's plan, which has battles on many fronts. Galignen sent his own worshipers to Thornburg Keep, infected with the Red Rot, to close the healing sanctuary down. His next move is to retrieve the Vemora for himself. Unfortunately, the Red Rot drew on far more of the god's power than he calculated (and he was perhaps badly defeated in his attempt to retrieve another Vemora elsewhere). Galignen has spent 80 years recovering his power - but what is a century to a god? He is ready now to reach out and seize the Vemora. He has sent his worshiper Shirek the Ghantu to do this. When the Vemora is brought back to him, it will become Galignen's Chalice of Plagues, restoring a large measure of his power to create diseases. The Red Rot Galignen developed this plague in collaboration with his brother Necros. It is a hemorrhagic fever (rather like Ebola) which covers the poor victim in blood-seeping sores. Worse, the corpse of a victim is reanimated as a Plague Zombie. Galignen intended the Plague Zombies to overrun Thornburg Keep and bring the Vemora to him themselves. He was thwarted in this. The master Healer of Thornburg Keep was wise enough to burn the infected corpses and evacuate the Keep. Exhausted, Galignen allowed the plague to fall dormant. Now he's ready to try again, but this time he won't trust in zombies! Shirek and the Plague Cult Most of Galignen's cultists are sentient flora, but he has a few fleshy worshipers like Shirek and his Higmoni lieutenant Voork. The Higmoni's natural regenerative powers enable them to endure the Red Rot for far longer than other creatures: they believe that, if they are successful in their mission, Galignen will cure them, but they are surely mistaken in this. Shirek is a true acolyte of the cult and bears countless infections and fungal growths on his flesh, but Galignen's power makes him immune to them: he is the example of the god's power that inspires the Higmoni to put up with the infection they endure. However, should he succeed in his quest and bring back the Vemora, even Shirek will be abandoned to die or, at best, be transformed into a shambling plant. Shirek has set his minions to work ransacking the dungeon, looking for the three keys that unlock the Vemora, but has so far come up with nothing. Worse for him, the Cavasha has set up its lair in the Keep and (unwittingly) guards the only route through to the Throne Room where the Vemora is kept. If only Shirek knew about that teleportation arch. Let's hope no one tells him! Belisma Mort's ill-fated Company The Keep is strewn with the corpses of an unlucky band of adventurers who entered the dungeon a few weeks ago. This was the party of Belisma Mort, a Dunnar enchanter. They spent some days exploring the dungeon but bit off more than they could chew when they descended to the second level. They found the silver key in Captain Voln's quarters, but lost it when their Dwarf was captured by the giant spiders. Belisma was blinded when they disturbed the Cavasha and they fled back to the infirmary where they discovered another companion, Sezzerin, had contracted the Red Rot. One by one the adventurers succumbed to the Rot and reanimated as Plague Zombies, leaving Belisma as the last survivor, starving, blind and mad with fever, holed up in a remote guard post. This provides a bit of character for the anonymous corpses and the threat that, one by one, they will reanimate as Plague Zombies. If Belisma can be rescued, she will parley her map and information about the silver key for escort out of the dungeon - but this will put the party into conflict with Jacca Brone. Jacca Brone, the Dingleman Instead of being a pointless priest of Shalmar, Jacca Brone is beefed up to be the Dingleman overseeing Thornburg Keep. After all, this is a royal residence that holds a royal heirloom; moreover, it's a quarantine site that might still harbour a deadly infection. Jacca's job is to prevent greedy treasure-seekers (like Belisma Mort's hapless crew) breaking into the Keep. I've redesigned Jacca as a competent Beast Mage whose spells make him very effective at detecting intruders and negotiating the perils of the dungeon. He now features on the Wandering Monster table for the first level of the dungeon, which he patrols (looking for Shirek, whom he observed entering the site). Jacca's presence creates very different outcomes depending on whether the PCs are chartered adventurers in the service of the local King (unlikely) or trespassing treasure seekers doing an illicit favour for the local peasants (more likely). If the latter, then Jacca will turn the party away at the Keep's entrance: they need to sneak back later while Jacca is off patrolling and avoid him at all costs if they meet him in the dungeon. Yes, they could attack and kill him, but he's a royal officer so that's a crime that carries a capital punishment for all concerned. If the party can find a way to parley with Jacca (especially as the threat of the Red Rot grows), he has lots of information about the dungeon layout, the three keys, Shirek's incursion and the Cavasha. Of course, he won't let infected people leave the site - but he ends up becoming infected himself, as you will see. The Events that tell the tale Every time a Wandering Monster is indicated (10% chance, every hour), then next Dungeon Event occurs from the sequence of ten. These include things like Belisma's last companion dying and reanimating, Belisma dying, Shirek moving around the site, Plague Zombies animating and all the Giant Rats in the site becoming infected too. Among these Events, Jacca Brone becomes infected, which might well alter his negotiating position. This creates a linear narrative, as the plague spreads across the dungeon, infected corpses rise as zombies and the humanoids assemble to do battle with the Cavasha. There are now lots of opportunities for players to ally with or exploit the different factions - or just creep through the dungeon trying to avoid the mayhem. There's another collect-the-set mission, since the Master Healer's ledger now contains a cure for the Red Rot, which (naturally) involves the Cavasha's eyeballs. Reflections I'm very fond of The Vemora as a tutorial dungeon, but there isn't a great need for such a thing among my players. The Expanded Vemora upgrades the scenario into something more complex and dangerous that experienced players will enjoy. The Plague Zombies also replace quite a few of the tedious blood-drinking bats and acid-spitting crabs that pose pointless threats in the original. I'm a big fan of dungeons with a timetable of events: things that will occur in a certain order, with NPCs and monsters moving around, dying, capturing treasures, etc. This makes for a dynamic dungeon where adversaries do not simply sit in their rooms, waiting for PC adventurers to turn up and fight them. It also means that, if the players go away then come back again, the dungeon will have changed in their absence. The Red Rot makes a nasty adversary in its own right, creating drama as the players start showing symptoms. There is a chance that tough PCs on full Hit Points might survive the illness, but for most this introduces a terrible urgency to the exploration of the dungeon. Galignen as the background villain links the events in the scenario to Forge's intriguing mythology. As last-god-standing, Galignen hopes to make the last and decisive move in the God-Wars and claim the entire world for himself. The need to locate and secure the other Vemoras and perhaps take the fight to Galignen's Cult and the demi-god himself is a worthy plot for an epic campaign.

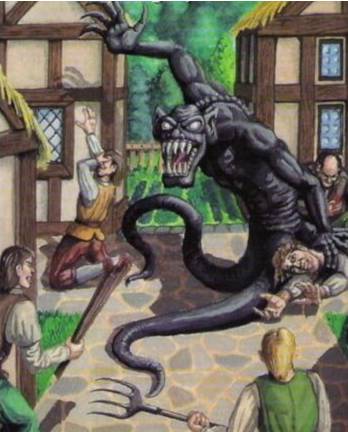

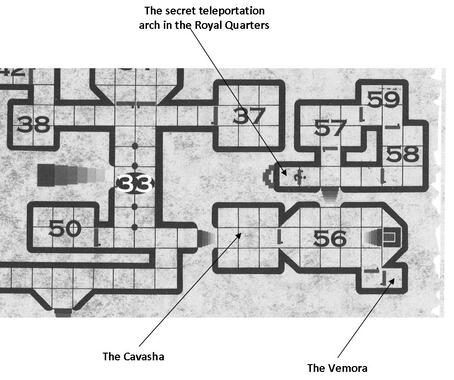

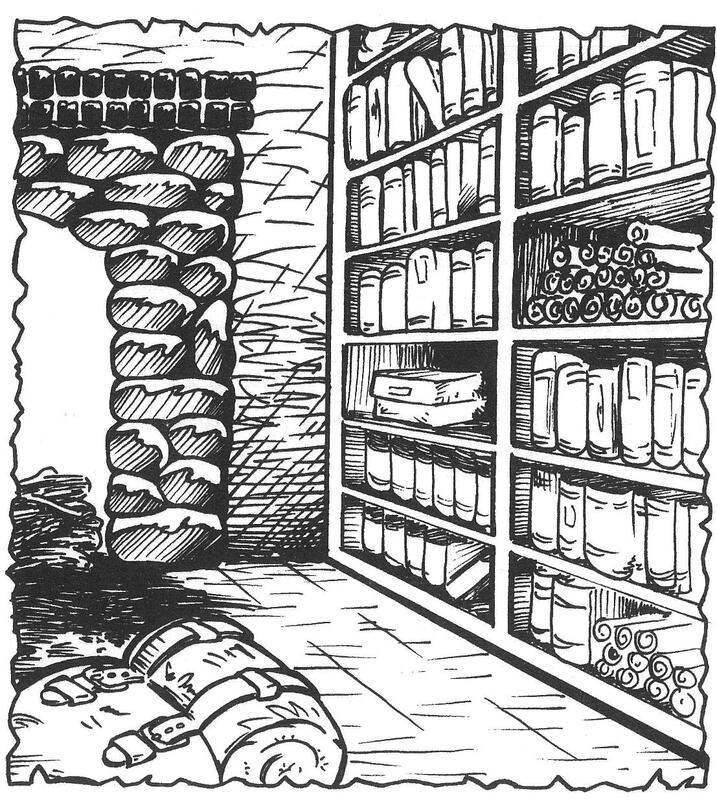

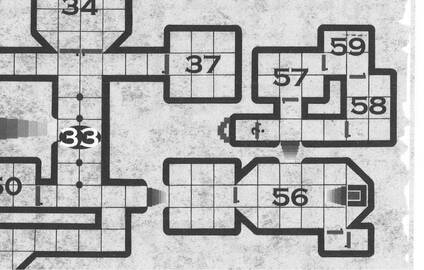

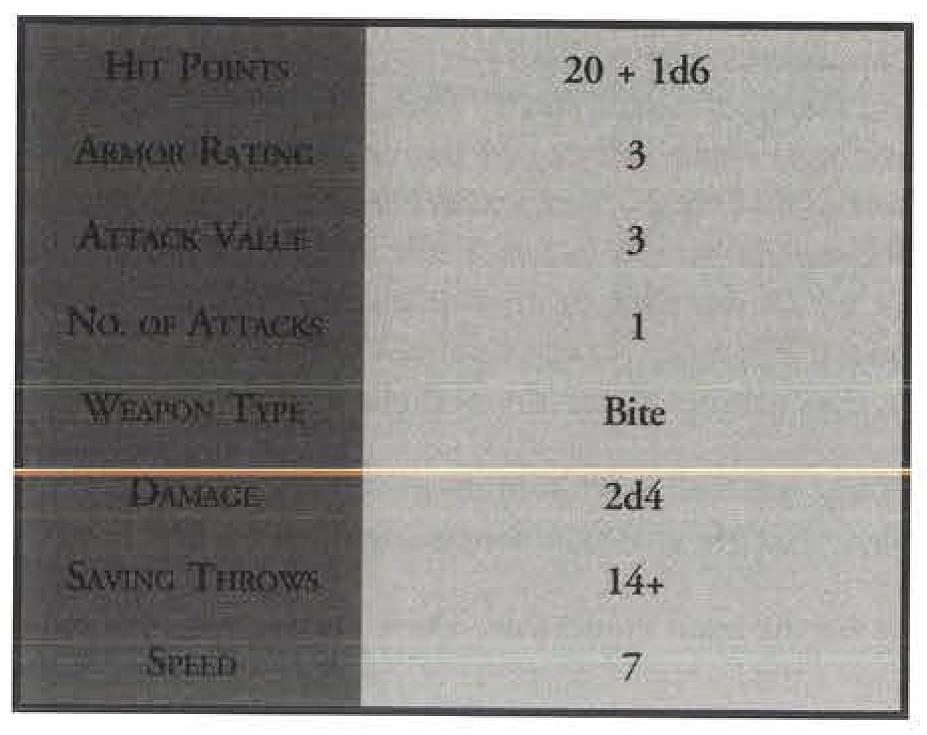

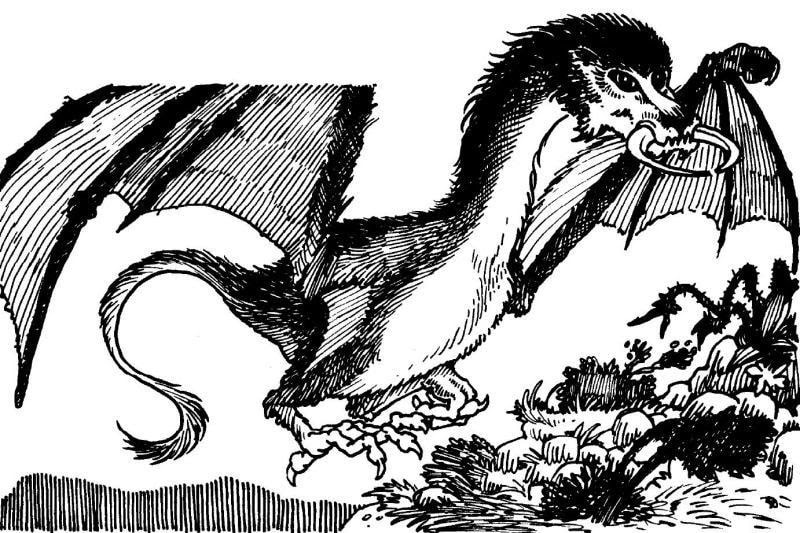

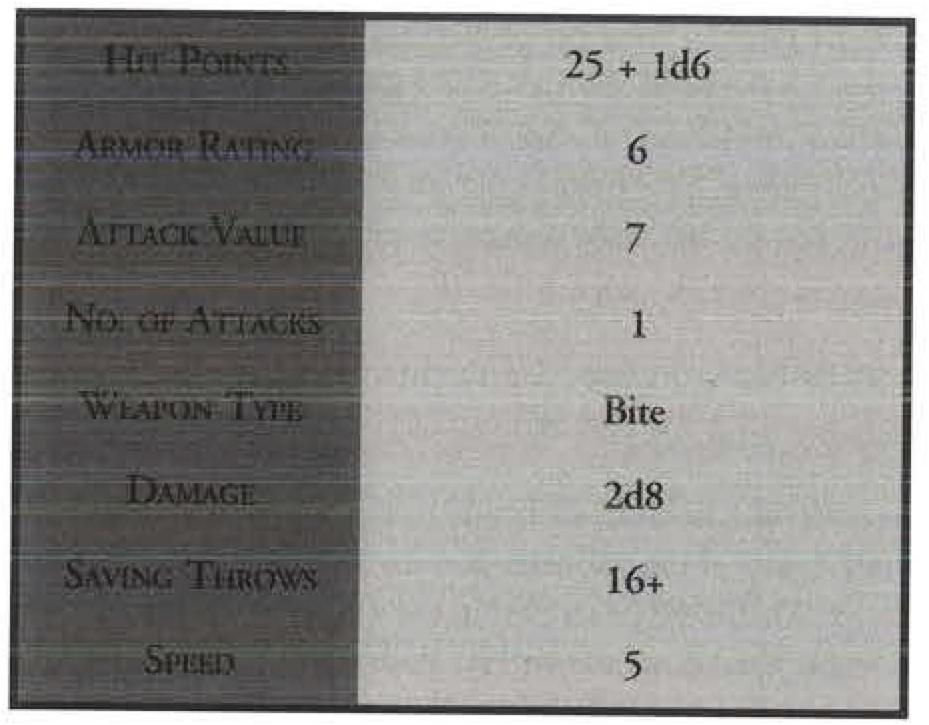

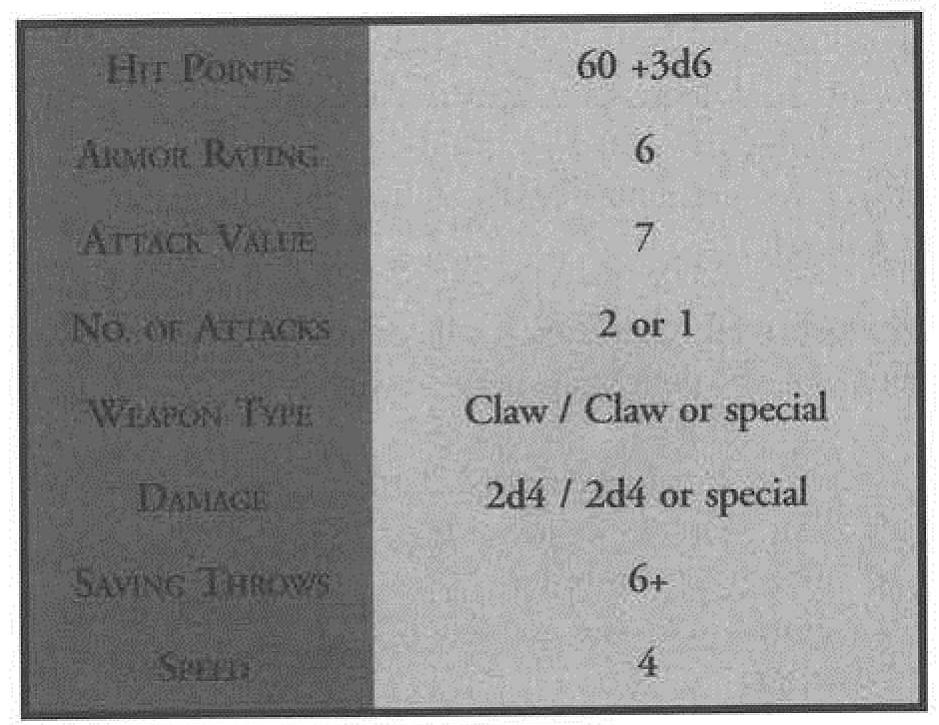

The Vemora is the first scenario published for Forge Out Of Chaos by Mark Kibbe back in 1998. It retailed back then for $7.98 and consists of a 28-page staple-bound book with colour cover art (by Paul Butler) and some B&W interior art (by Mike Connelly & Don Garvey who worked on the original rulebook), including two maps and lots of drawings of rooms and enemies discovered during the scenario. There's a detailed NPC and two new monsters (mutant animals, nothing special) and a small amount of information about the setting. For me, the product is interesting for what it reveals about the sort of game Mark Kibbe thought he had created; now, two decades later, there are copies for sale that cost less than the original RRP and DrivethruRPG sells a PDF for $6 (without the slipshod reproduction that ruined the PDF rulebook). Background The scenario is set in the realm of Hampton, which is one of those place names that sounds very Olde Worlde if you're American, but not if you're British. Nearly a century ago, High King Higmar ordered the construction of Thornburg Keep and its underground sanctuary to house a precious healing artifact, the Vemora. Then a plague arrived that proved resistant to all medicine and magic and Higmar ordered the evacuation of his stronghold. Since then, monsters have moved in to inhabit the underground levels (as they do!) as well as a couple of groups of marauding humanoids (Higmoni and Ghantu) looking for loot. The Vemora itself remains hidden and inviolate, deep underground. The Hook Rumours of adventure bring the PCs (rootless mercenaries, as per standard) to the village of Dunnerton. Recently, the monster known as a Cavasha attacked the village and blinded its defenders, including the Elder's son. The Elder wants the PCs to hike out to Thornburg Keep and retrieve the Vemora, to use its magic to heal his son. If good deeds aren't a motivation in and of themselves, he'll pay 300gp. A scout will take the PCs to the dungeon entrance and a local Elven healer will accompany the party out of sheer goodwill. The cover of the book (by artist Paul Butler) depicts the very Lovecraftian Cavasha attacking the village. It's an exciting scene, with villagers falling blinded after it uses its gaze power. Unfortunately, the Cavasha itself never features in the scenario, so this picture is a tease, really, since the Cavasha definitely lives up to what the rulebook calls its "gruesome appearance" (p165). The buildings in the village and the style of dress (breeches, lace collars, jerkins) suggest a 17th century setting, rather like Europe during the Witch Trials and the Wars of Religion (or perhaps Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay). I wonder, is this really how Mark Kibbe envisaged Juravia? It's certainly very different from the Post-Holocaust/Dark Ages vibe I detected in the rulebook. Dunnerton Dunnerton is sketched out in essential detail only. There's a Dwarven smith, Brundle Jove, who will offer free armour and weapon repairs to PCs working for the Elder; however he has a finite number of repair kits so there is a limit on the number of APs he can restore. A Sprite trader named Dya Brae runs the store and a list of the resources she has for sale is provided along with the exact amount of each (e.g. she has 5 Healing Roots in total). Alongside her wares, she dispenses some in-character dialogue that mixes inane wittering with nuggets of good sense. The Drunken Dragon Inn offers lodgings and a brief rumour table: the untrue rumours are far more interesting than the actual dungeon itself, which begs the question why the author didn't make use of these ideas! There's a temple of Shalmar, Goddess of Healing and the priest, an Elf named Jacca Brone will accompany the party if they need a healer. His character sheet is provided in full along with some pointers for the GM to roleplay him. There are no subplots going on in Dunnerton, which is always a shame, but the scenario is explicitly pitched at first-time-roleplayers so perhaps that extra layer of complexity is unnecessary. I like the recognition that local smiths and traders don't have unlimited supplies to service adventurers. Providing Jacca Brone is a nice touch, especially if newbie players neglected to take the Binding Skill or avail themselves of a Berethenu Knight. The presence of a Temple of Shalmar left me scratching my head. The gentle Shalmar was murdered by her brother Necros during the God-Wars. Indeed, this blasphemous crime seems to have triggered the wrathful return of Enigwa and the Banishing of the gods from Juravia. What can go on in a Temple to Shalmar? How (and why) do you worship a defunct goddess who can neither respond to prayers nor acknowledge worship? Maybe Shalmar-worshippers are a bit like certain Church of England Vicars: they don't really think their deity exists, but they respect the sort of things she stands for. That's nice, but why a tiny community beset by monsters would support a temple to the beautiful concept of healing, rather than building a temple for and funding the services of, say, a real live Grom Warrior who can kick monster butt, is a pressing question in my mind. The Dungeon, Level 1 The back cover art shows the scout directing a band of adventurers towards the dungeon entrance, which is a broken door set in the hillside, surrounded by carved pillars and steps and all overgrown with ivy and moss. The party includes a big barbarian warrior with a hilarious bald-patch, what look like a dwarf and an archer and a Merikii with his signature two-sword pose. Dungeon level 1 has 32 rooms, very much in the densely-packed Gygax-style rather than the sprawling Holmsian aesthetic. If the PCs press on in a straight line they will pass through the two entrance halls, the Dining Hall and the Great Hall, ending up in the Library where they have to tangle with a Tenant, which is a Mimic-like creature that inhabits wooden objects with a very nasty attack. Along the way, they will come across lots of mosses to test their Plant ID skills on, magical fireplaces which add a much-needed spine-tingling moment to proceedings, possibly find a magic dagger and end up securing some valuable tomes and clues about the nature and location of the Vemora. They will also have a modest skirmish with crab monsters and possibly fall through one of those pit traps that deposits them in the abandoned cell block in Dungeon Level Two, with all the fun that this implies. The trap only triggers if the party numbers 3+, which is an elegant touch: small parties (or cautious ones) are spared this complication. Rooms 1, 2, 4, 5 and (mind the pit trap) 30 take you to the Great Library (#32) and a nasty monster If the PCs venture away from this central spine, things get a bit more varied. Up to the north there are acid-spitting crabs, a teleportation gateway that takes explorers directly to the Royal Chambers on Level Two (but allows them to return, unlike the pit trap), giant rats, giant centipedes, minor trinkets and a guard room explicitly intended to be a safe base for adventurers to make camp. Those who have played D&D Module S1 (Tomb of Horrors) will be wary of this North definitely equals 'safe' and the teleporter offers the intriguing possibility that hapless PCs could blunder straight into the Vemora's hiding place - but of course they won't have the special keys needed to get at it yet. This offers a cute glimpse of where the PCs need to end up and a way of getting there quickly once they've assembled all their keys and clues. The southern rooms are a bit livelier. There are armouries to ransack, more rats, crabs and blood-draining bats to fight as well as a Creeper, which is an acidic slime. There are mysterious tracks to decipher (cue: Tracking and Track ID skills) that reveal you are not alone: Shirek, a tough Ghantu, and his Higmoni henchmen are camped down here. Shirek is the main 'Boss' on this dungeon level and there will be a communication barrier unless someone speaks Ghantu or Higmoni, in which case a fight can be avoided. The set-up here is exemplary: first the signs of ransacked rooms, then the tracks, then the Higmoni, then the appearance of their one-eyed boss. The designer makes some questionable assumptions. The main rulebook introduces a Languages skill but doesn't encourage anyone to learn it, saying "all character races ... speak a common language known as Juravian" (p23) but at the same time each character "is fluent in its own language ... as well as the Juravian language" (p5). The chances that a group of PCs will not include at least one bestial Higmoni or giant one-eyed gorilla Ghantu are (knowing the aesthetic choices of dungeon-bashing players) slim. This means players are highly likely to defuse this encounter non-violently unless they are immensely dunder-headed. But this is supposed to be a teaching dungeon, so that's probably how it should be. The Dungeon, Level 2 The lower dungeon level has 27 rooms, arranged in a sort of loop, with a spur off to the north (the old cell block where the pit trap deposits you) and the south-east (the Royal Chambers where the teleporter takes you). There are several ways down here. The pit trap is the worst: you're in the old cell block, with giant spiders nearby, and you don't know the way out. The teleporter is better: you discover the Royal Chambers and all their loot (including magic items and a magical sword) but you probably cannot open the difficult locks. You can stumble into the eerie throne room but you probably won't have the keys to get into the Vemora's vault. Try exploring further and you encounter the ravenous undead in room #36 (see below). Conventionally, you'll descend the stairs in the southern part of the first level. This brings you into a central columned hall with a fountain, magical roots to identify and the corpse of another Higmoni, tipping you off there are more raiders down here. Have fun exploring the temple rooms, dealing with killer mold and a Berethenu Shrine, which is a great asset for Berethenu Knights and offers a cute benefit for Grom-ites who choose to desecrate it. You soon discover the bedrooms, workrooms, smithies and studies of the castles old occupants and some of their correspondences. This is clearly inspired by the chambers of Zelligar and Rogahn in Mike Carr's seminal D&D Module B1: In Search of the Unknown (1979). There's a pleasant frisson to exploring the intimate chambers of these long-dead people and it's a valuable reminder that this labyrinth was not always a malevolent dungeon. There are a lot more Higmoni down here, split into two groups and leaving evidence of their looting all over the place. They're having a spot of bother with a pack of undead Magouls (why MAgouls? why not just ghouls? why???), so, once again, players who prefer to talk than fight might be able to negotiate something. The Magouls (that name, grr-rrr) are in room #36, which isn't keyed on the map, but it's the room outside the Throne Room #56 (perhaps another reason for smart players to double back and use the teleporter upstairs). Unkeyed room is #36, just off the main corridor (#33) and the only way through to the Throne Room (#56) Once the PCs have their three keys, they can head to the Throne Room (which may or may not involve confronting the undead) and retrieve the Vemora - naturally, its a big golden chalice. Then it's back to Dunnerton for the reward. Evaluation: non-Forge As noted, this is an exemplary tutorial dungeon for a novice group of D&D players. It has all the best features of Basic D&D Module B1, while being tighter and more focused. It's an underground fortress with a lot of empty rooms containing interesting objects and a few mystical moments when the magical fires light up; there are dungeon raiders who pose a challenge but can be negotiated with if the players aren't too trigger-happy; there's a pit trap to the lower level; there's a historical mystery in working out what the rooms once were and who inhabited them. In some ways, it does its job better than Module B1: the quest for the Vemora, and the collection of keys to unlock it, gives structure and purpose to the adventure, rather than aimless wandering. The nearby village of Dunnerton offers support and healing as well as a grand reward. D&D conversions are easy: giant centipedes, rats and spiders (albeit large spiders in D&D terminology) are standard; use stirges for Ebryns and fire beetles for Nemrises; 1HD piercers work for Bloodrils; the Creeper is an ochre jelly; the Tenant is hard to translate but a half-strength mimic would work (3 HD, 2d4 damage). The Higmoni can become goblins, their Leader a hobgoblin, Shirek the Ghantu translates as a bugbear or a gnoll. The Magouls are, of course, proper ghouls with proper names. The limitation of the scenario is that this is all it is. Exemplary tutorial dungeons are all very well, but D&D 5e includes The Lost Mine of Phandelver in the Starter Set, which is a far more ambitious introductory adventure than this. Even back in 1998, the sort of dungeon adventure The Vemora provides was pretty dated: it might perfect the formula of In Search of the Unknown, but that means perfecting something already 20 years old at the time. Nonetheless, if you play any sort of OSR RPG or any iteration of D&D and come across a cheap copy of The Vemora, don't disdain it. It's a little gem of an introductory dungeon that provides the right balance of mystery solving, exploration, combat and a sense of wonder. There's a bunch of noob adventurers out there who will remember it fondly if they get a chance to cut their teeth on it. Evaluation: Forge & adapting the scenario Although it's a great tutorial dungeon, The Vemora is a frustrating product for Forge Out of Chaos. Even in 1998, it was unlikely players were coming to a RPG like Forge as complete noobs. The rulebook makes few concessions to novices, since it commences with a treatise on the Kibbe Brothers' distinctive mythology rather than explaining what roleplaying is. It's very worthy that the scenario carefully points out every opportunity PCs have to use and check skills like Plant ID, Tracking and Jeweler but these sort of training wheels are certainly redundant. Instead, Forge players will be hoping the scenario sheds light on what's distinctive about Forge as a RPG: its themes, setting and conflicts. Yet here we are disappointed. The Temple of Shalmar and its priest Jacca Brone only goes to show that the authors have not grasped (or simply forgotten) the implications of their god-free setting. Forge promises a post-apocalyptic world, but the scenario presents a rather orderly one, with its well-run kingdom and 'High King'. The dungeon is not the mansion of a fallen god but something much more prosaic: an underground fortress that's only 80 years old. The ancient plague hints at darker designs, but is never explained and finds no expression in the dungeon itself: where did it come from? where did it go? why was it immune even to the Vemora's healing power? Then there's the hideous Cavasha from the front cover. With 25+1d6 HP and Armour Rating 4, it's a tough opponent but not beyond the means of a party of adventurers who have availed themselves of magical weapons. With Attack Value 3 and two claw attacks for 2d4, it's a Boss-level combatant for starting PCs and of course there's the permanent blindness from its gaze - though the Vemora's on hand to cure that. Surely the Cavasha, rather than those preposterously-monickered Magouls, should have its lair in room #33.

POST SCRIPT: This file offers a complete conversion to O/Holmes/BX/AD&D:

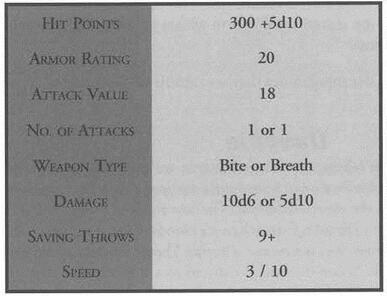

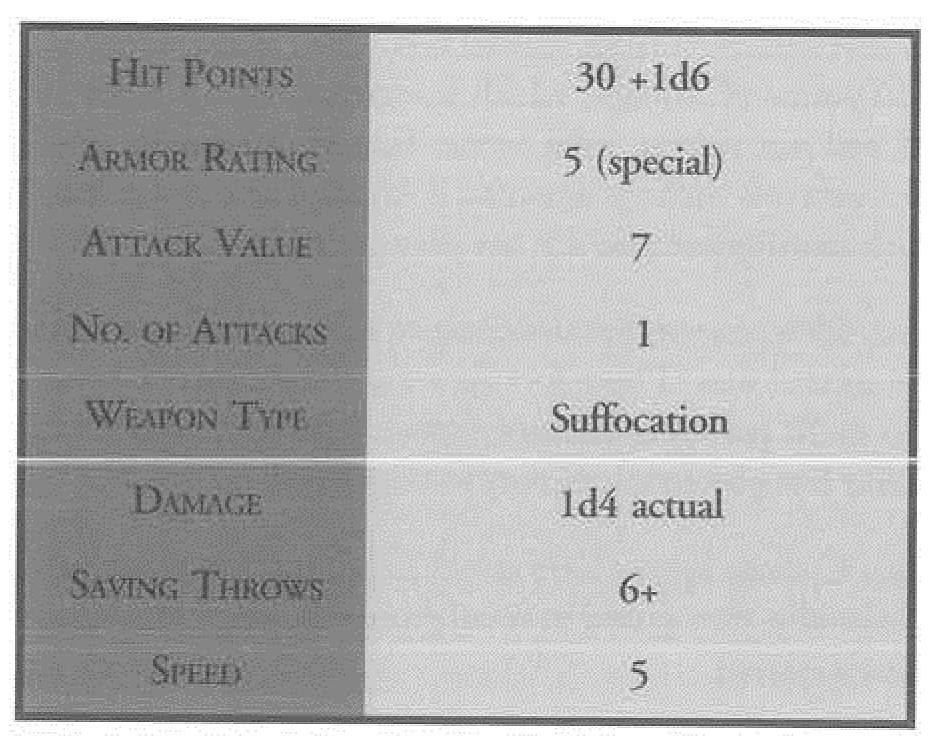

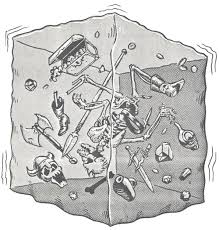

Developing the Dungeon The Rumour Table at the Drunken Dragon Inn suggests some other, far more interesting, plots within the dungeon. For example, there's the obligatory previous-party-of-adventurers who entered the Keep and never came back. Wouldn't it be better if some of them were still down there, wounded, starving and desperate? There's a rumour about the water being infected with the Plague: that's a good idea! The High King's ghost is supposed to haunt the Throne Room: Forge doesn't do spirits and incorporeal undead, but what if the Plague raised its victims as zombies? What if those previous adventurers are infected by the Plague now? What if there's a cure for it somewhere in the dungeon? What if the cure requires the ichor from a Cavasha's eyeballs? A dungeon like this needs a Dungeon Constable or Dingleman and it makes sense to cast Jacca Brone in this role (which makes more sense than a priest of Shalmar). The Referee has a choice: are the PCs chartered to enter the Keep by the current King, in which case Jacca is an ally who will show them in and offer directions to the Great Hall and warn about Higmoni incursions. Or (more likely) Jacca enforces the quarantine on the site and the villagers of Dunnerton are going behind their lord's back by recruiting adventurers to trespass on the site and retrieve the Vemora. In this case, Jacca is an adversary and wandering monster (on the 1st level) who must be avoided at all cost. If you add the Cavasha to the dungeon, then the Dingleman will know that it lairs somewhere on the 2nd level; he probably warned Dunnerton of its approach when it went marauding out last month. If the PCs have a (self-appointed) mission to destroy it, the Dingleman might allow even unchartered adventurers entry and guide them to the stairs - but will expect them to hand over treasure and magic items when they leave (including the Vemora - it's a royal heirloom). That creates a dilemma since the PCs swore to bring the Vemora to Dunnerton... See how much fun Dinglemen add to a dungeon? Mark Kibbe's decision to frame the scenario as a tutorial dungeon was a mistake, creatively and (I suspect) commercially. But if the dungeon architecture is robust - and this is - then it's easy to adapt it to a more complex story. Removing a few of those acid-spitting crabs, mutant rats and blood-draining bats is step one; replacing them with tragic plague victims and plague zombies is step two. Then there needs to be a cure among the papers in the Great Library (#32) with ingredients to be gathered from various mosses, roots and monster body parts around the site, the whole thing to be brewed up in the Vemora chalice to save the NPCs (and, by that point, PCs too) who are infected. That would be a scenario even experienced players would get behind and, even if it doesn't do justice to Forge's setting, it would pass a merry couple of evenings.