|

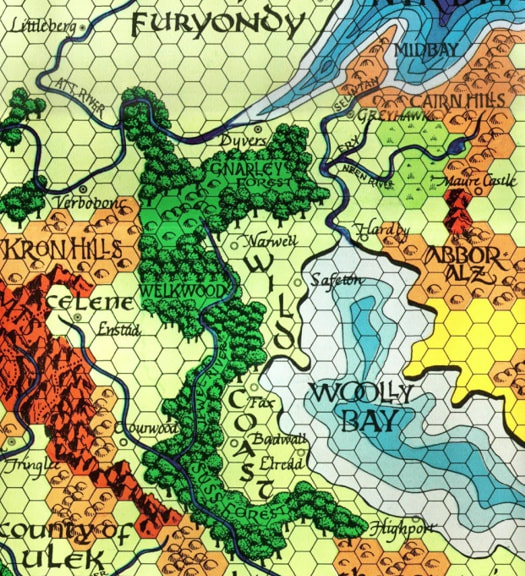

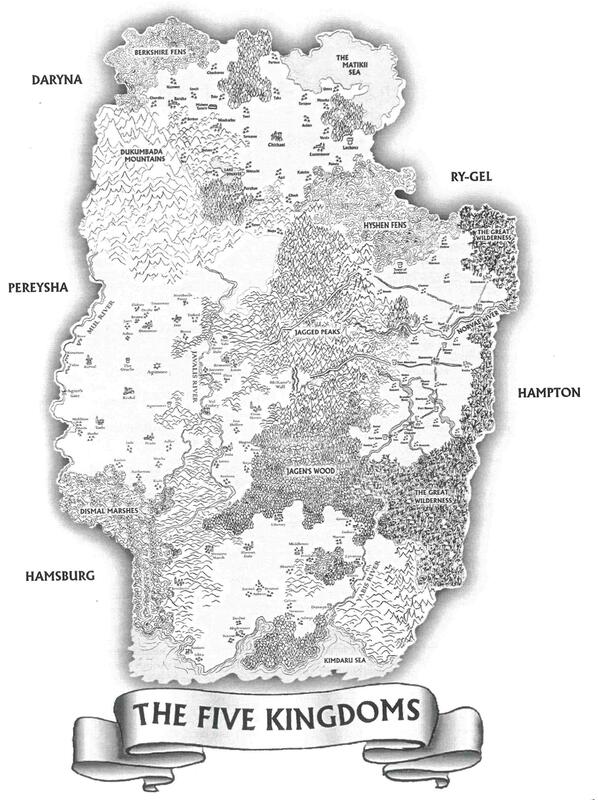

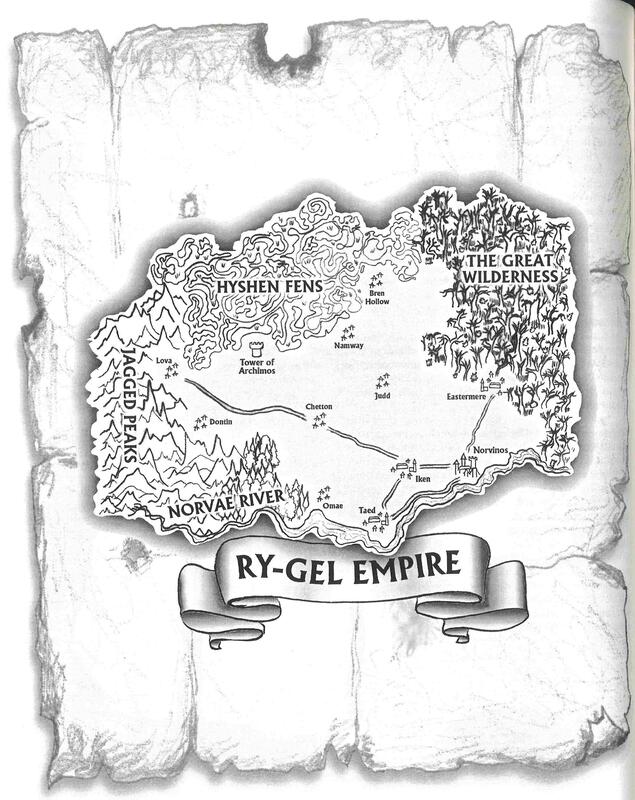

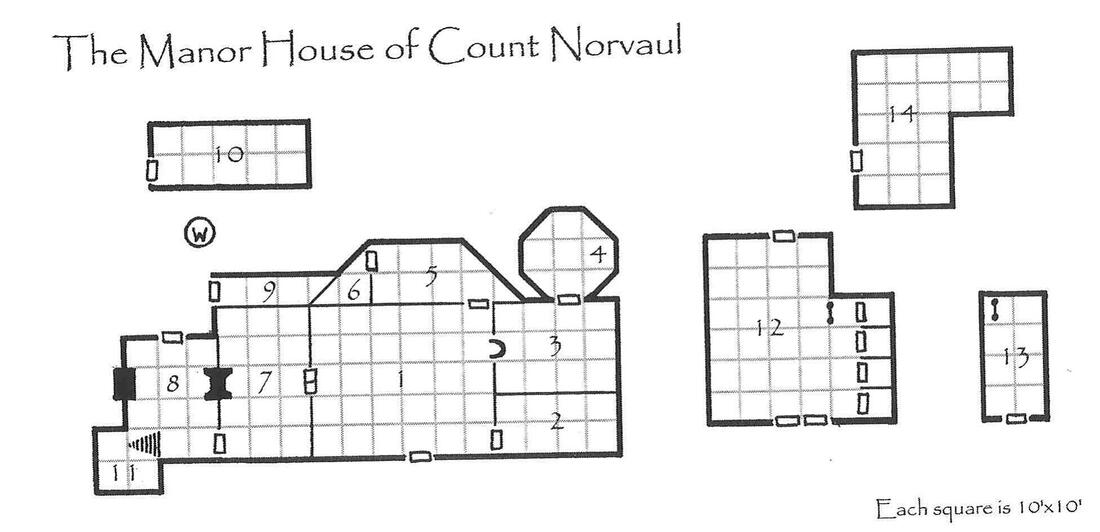

Over the past few months I've reviewed the 1990s "fantasy heartbreaker" Forge Out of Chaos and analysed its main rules, themes, monsters and the two published scenarios (The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell). It's a game with an identity crisis, setting itself up as a meat-and-two-veg dungeon crawler set in a ruined world where the gods have been banished, but then being recast as a sort of Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay imitator, set in a Renaissance or Baroque world with a lot of politics, economics and a Gothic palette. More on that shortly. This is the last product to be published for Forge Out of Chaos, back in 2000. The previous module promised an ambitious campaign pack (called Hate Springs Eternal - great title) in November 1999, but that never appeared. Instead, the sourcebook arrived, rather optimistically bearing the "Volume 1" subtitle. After that, the presses at Basement Games fell silent. I wonder what was planned for Volume 2? The World of Juravia is a 170 page book that retailed for $19.95 - expensive for back then: this is the same price tag as the original Forge rulebook itself. The old team of Mike Connelly & Don Garvey is gone; there's a range of art in here, notably Jim Pavalec, who does the cover art, and Shella Haswell, who produced the back cover and has a rather different, highly stylised approach. The interior art varies a lot in quality but is mostly solid fantasy fare. Pavalec's cover suggests a return to the game's conceptual roots: a sinewy, barbaric figure (a Higmoni, judging by that be-tusked jaw) is ambushed by a many-headed snake (perhaps a Tursk, but they are supposed to have two cobra-like heads). The stylised nudity, the languid athleticism and the rearing monster, all seem to reference Boris Vallejo's art for Conan (minus the naked chicks: to its credit, Forge never went in for that aspect of old-school fantasy art). Gone are the breeches and lacy collars worn by the villagers in The Vemora: this looks less like 17th century Europe, more like pre Ice Age Hyborea. This statement of muscular intent is backed up by the back cover blurb: Welcome to the World of Juravia ... a paradise lost! Once a land graced with beauty, it is now a scarred wasteland of desolate swamps, jagged mountains, and hideous creatures beyond imagining. This echoes the contextual fluff on the back of the original rulebook: It was once a paradise but is no longer! Once beautiful landscapes are now swamps, desolate wastes and jagged mountains. The calm and gentle rain has turned to fierce storms of fire and ice. It's tempting to read this as a return to the game's roots in a gritty post-holocaust environment, rather than the genteel and civilised setting described in Tales That Dead Men Tell. What's inside? - A Calendar! Yes, we start with the Juravian Calendar and it appears to be the year 679: that's 679 years since the gods were Banished. The first 300 years seem to have passed in murky confusion but in the last two centuries there has been some sort of Renaissance and an international calendar has been developed. Four pages set out the days and months of the Juravian year and its major festivals, which honour the gods, especially Omara, goddess of harvests. There is reference to the "church of Enigwa" (the creator-god) and its year-end tradition of burning alive all wizards! Let's dispense with the oddity of kicking of your world-building sourcebook with arcane stuff about calendars. Gary Gygax did it with the 1st edition AD&D World of Greyhawk Gazetteer and if it's good enough for Gary... Yes, I assume that author Mark Kibbe followed (rather uncritically) Gygax's AD&D template for what a world sourcebook ought to look like. Critic Ron Edwards rages against this sort of thing, complaining, in his famous essay on Fantasy Heartbreakers (2002), that games like Forge "represent but a single creative step from their source: old-style D&D." But I'm rather touched by the humility of it: Mark Kibbe is homaging the World of Greyhawk, right down to Gygax's highly idiosyncratic ersatz-scholarship. But never mind that! The eye-rubbing is in the details. What was implied in the previous modules is explicit here: in Juravia, the gods are still being worshiped and that worship is led by a professional priestly class. To grasp the weirdness of this you have to steep yourself in Mark Kibbe's iconoclastic mythology - but since his mythopesis takes up the first 11 pages of the Forge rulebook, you'd be forgiven for supposing the author wanted you to do exactly that. These are the gods (let's recall) who joined together to create humanity, then set about warping and mutating humans into the demi-human races and into monsters to function as soldiers and artillery pieces in their planet-shattering war, a war which led to their banishment from Juravia, the utter annihilation of one of them and the eternal perdition of two more. Why would anyone who believed this mythology want to worship these beings? And since they cannot answer prayers or grant spiritual comfort, what would be the point? It makes sense that creator-god Enigwa would stll be worshiped and it makes sense that his 'church' would condemn Mages: in Juravian myth, Enigwa forbade the gods to teach magic to mortals. You would think the Enigwa-ists would be just as hostile to the worship of other gods, especially Gron and Berethenu, since Enigwa sentenced these two deities to Mulkra (Hell) for their role in the God-Wars. If the "Church of Enigwa" promotes Deism (the belief in a virtuous but non-interventionary God) and indulges in Wizard Burning, then we are very clearly in the equivalent of Europe's 17th century here. I don't mind that: a world inspired by the Witch Trials of Bamburg and Salem has appeal. But I'm surprised. The main rulebook gives no intimation that Mages are hated outcasts or that anyone choosing a Mage profession is putting a target on their back, courtesy of those fanatical Enigwa-ists. Moreover (and this is oddest of all), the rest of the gazetteer barely refers to it again. The Five Kingdoms - sort-of France, or maybe Massachusetts There's a map of the campaign setting of 'the Five Kingdoms' and it is (for its time) nicely done and in the same format as Tales That Dead Men Tell. There's a massive central mountain range (the Jagged Peaks) and the Dukumbada Mountains up to the north-west, creating a passage between them linking the northern and western regions. The northern kingdom is Daryna, which is suggestive of Poland, bordered by dense swamps and a sea coast. The Merikii bird-people live here and it's pretty isolated. The region is not an island - rivers, mountains and forest form natural boundaries Over to the West is a large 'empire' called Pereysha, bordered by rivers and more marshes. It seems to have a sort of Franco-German feel. There's a massive forest south of the Jagged Peaks called Jagen's Wood and that separates Pereysha from coastal Hamsburg, which was the setting for Tales Dead Men Tell and is perhaps Mediterranean in tone. East of Jagen's Wood and the Jagged Mountains (but connected to Pereysha by a strategic mountain pass) is Hampton, the setting for The Vemora; however, this version of Hampton makes no reference to a 'High King' called Higmar and the village of Dunnerton does not appear on the map. Finally, north of Hampton but cut off from Daryna by the enormous Hyshen Fens, is weird Ry-Gel, which I'll discuss in a bit of detail, since it's the most clearly fantastical of the realms. The map is only a sliver of a wider continent. No scale is given (an odd oversight) but based on the textual references, the region seems to be about 500 miles east-west and twice that north-south. In other words, these 'empires' and 'kingdoms' are squeezed into a territory the size of France. Off in the wings, beyond the map, are the larger polities of Jucumra and Brattlemere and an Elvish realm of Elladay; however, natural barriers (especially the 'Great Wilderness' to the east) lock this territory off from the wider world. The Merikii are the indigenous peoples of Daryna, but the other kingdoms are former colonies of those off-stage empires. This starts 491, with Hampton being founded by pioneers from Jucumra making their way through the Great Wilderness, like Daniel Boone crossing the Cumberland Gap. The Jagged Mountains are seething with Higmoni War Camps and in 533 these erupt out, causing the Blood Wars. Various offstage empires contribute troops and the victors carve out Pereysha over on the other side of the mountains and then Hamsburg, a Pereyshian colony, wins its independence in a brief revolt in 587. Ry-Gel seems to stand apart from these events. It is discovered by pilgrims crossing the Great Wilderness in 301, a bit like the Mormons arriving in Utah, and it fights its own battles with the Higmoni a couple of centuries before the Blood Wars, then it falls under the rule of a wizard named Nanghetti who becomes a usurper and has to be destroyed by an order of paladins. Ry-Gel stays out of the Blood Wars but is rocked by famine and plague. it bans all religion and is ruled by a corrupt and decadent Triumvirate. It is far and away the most interesting of the Five Kingdoms. Nanghetti's return from the dead was supposed to be the plot for Forge's module-that-never was, Hate Springs Eternal. The Ry-Gel 'empire' seems to be about the size of Wales Analysis The names are, I think, misleading. Pereysha is called an 'empire' and so, on occasions, are the other realms. Secundum literam, they are not: they haven't expanded beyond their national borders to conquer or colonise other peoples; they're not multi-ethnic supra-states. Calling them 'kingdoms' also seems to be hyperbolic. They're more like the duchies of Medieval France or the protectorates of Renaissance Germany. No, what they are really like are the early American colonies. Hampton, with its robust citizen militias, gender equality and big university would be Connecticut; Hamsburg with its archaic gender roles would be somewhere like Catholic Maryland; Pereysha is big, rich Virginia with its trade ties to the Old World. Daryna is isolated and full of 'natives': the Great Plains, maybe Oklahoma. Weird Ry-Gel with its pilgrims and paladins and reactionary secularism could be Quaker Pennsylvania or Puritan Rhode Island. This piece of interior art seems to me to capture the tone of Mark Kibbe's setting better than strapping barbarians or robed wizards The US Colonies analogy gives me a clearer sense of what author Mark Kibbe was reaching for. These aren't barbaric territories, despite the front cover art, but they border onto unexplored and dangerous wilderness regions. The 'kingdoms' are small in population, experimental in political structure and have a relatively short history. They're all related to each other. They're all friendly. Moreover, they're economically productive and intensely liberal. Yes, there are few quirks, like Hamsburg's treatment of women and Ry-Gel's treatment of religion, but these are very modern cultures. All of them win their independence more-or-less bloodlessly because their parent empires prefer to trade with their former colonies than hold them by force. It's like an American 'civics' class with monsters. Bad rulers are deposed, usually peacefully, by dissatisfied commoners. Ordinary people go to university. Official documentation entitles people to travel and trade (it's not clear if the printing press exists, but the political sophistication surely suggests it does). It's all quite idyllic. Which, of course, makes it a bit dull. The troubling idea of a 'Church of Enigwa' persecuting Mages is never touched upon again. Sure, bureaucratic Pereysha can be a bit burdensome for free-wheeling PCs, but despite the exemplary detail in the regional descriptions, there's very little conflict for players to get caught up in. There's not much ethnic hate, or unresolved grievance, or seething discontent. The worst people in the Five Kingdoms are the 'Rats Nest', a Thieves Guild that destabilises the Hamsburgian Province of Newton. The Rat's Nest gets a thorough description, but you still don't feel motivated either to join it or destroy it. Ry-Gel is a bit of an exception, with its mystical past, it's unusual (and corrupt) government and its intolerant laws. You can feel adventures brewing in Ry-Gel, if a covert missionary wants to preach some crazy new faith and recruits the PCs as guards - or if the PCs get recruited as inquisitors to root out cells of cultists. But the main problem is lack of cultural focus. Every village and town gets a small entry, each leading NPC gets named, but the world of the Five Kingdoms remains shadowy. There's a solid idea for a setting here, but Kibbe focuses on the peripheral details and lacks the insight into human darkness needed to imbue his world with conflict and drama. Kibbe seems to struggle to imagine that rational people wouldn't sit down and solve every problem peaceably, so that's what his NPCs tend to do. It's a world that feels SAFE and not in a good way. The Dungeon Architect The next section of the book is the Dungeon Architect which appears to be made of material originally posted on the Basement Games website. There are 24 locations, each with a clear map and key, background and suggestions for inclusion in a campaign or using as the basis for a scenario. One of the larger locations, an abandoned manor house in Hamsburg that is being auctioned off by the state and could be bought by PCs for 157gp (you see how orderly and cosy this setting is? no need to bribe clerks or flatter aristocrats in sensible Hamsburg!) The selection includes inns, abbeys, the University of Nyanna, abandoned hermitages, crypts, cave systems and temples of Grom. The value of this sort of thing is immense, offering day-to-day locations where the PCs live, relax, work or research along with more mysterious locales that an be the basis for adventures. Mark Kibbe's rather prosaic imagination is ideally suited to this sort of architecture: lots of maps, sensible room descriptions, attention to details like estate income and access to fresh water and a few rumours and legends. An entire book of these would be invaluable for anybody's campaign, using any system. The last six pages of the book are taken up with a 'Rumours' section, which also seems to have come from Basement Games' website, presumably reflecting the designer's house campaign with contributions from some of the game's fans. These are fine: any and all could serve as plot-hooks. But none of them is particularly striking: there's nothing eerie, baffling, horrifying, intriguing or epic going on in Juravia: just expeditions, bandits, criminals on the run, missing children, kidnappings, tax collection and (this is good) the burning of a magic-wielding infidel by the Church of Enigwa. You want to know more about this Mage-hunting Church and less about tax collection, but as usual the setting seems to focus on all the wrong things. Amnesia - the last scenario We never got to see Hate Springs Eternal, but the Juravia sourcebook includes the third and final Forge module, a scenario called Amnesia which holds its head up well alongside The Vemora and Tales That Dead Men Tell, i.e. it's the sort of thoughtful, low-key adventure that would have been a classic if White Dwarf had published it in the '80s but which lacks the ambition or originality to rescue the Forge franchise from obscurity. The premise here reminds me of the old AD&D Module A4: In the Dungeons of the Slave Lords. The PCs awake in an underground cavern without their equipment and must find their way out, relying more on wits and roleplaying than conventional combat. Erol Otus' art is so witty: the PCs beat down on some small mushroom people but look what's approaching in the distance... In Amnesia the situation differs slightly: the PCs have armour and weapons but do not have any memory of where they are or how they came to be there. The scenario functions as both a trap and a puzzle, since the players must figure out what has been going on from clues they come across underground - including an angry Dwarf who knows them well and has good reason to hate them, although the PCs have no recollection of meeting him before. It's only 10 pages long, but the detail, layout and plotting is faultless. Mark Kibbe excels at this sort of thing: the classic dungeon-based scenario, done well. The players start off with limited light source and no map-making equipment and will soon find themselves in darkness, going in circles, unless they are clear-headed. Soon, they will acquire much-needed equipment and start to piece together that they are in a slave camp, with formerly-brainwashed prisoners who have been working the copper seam. The mine contains dangers of its own as well as shocks when the PCs discover that, in that period of their lives they have forgotten, they were not the slave workers in the mine but the cruel guards and overseers! There are several possible exits, one of which involves a very nasty fight with armed and armoured guards (always a tricky proposition given the way Forge's combat system works) and the other two involving an element of roleplaying with distrustful or hostile NPCs. The scenario concludes with some intrigue and politicking. The mystery is explained by the activities of one of the monsters from the Forge rulebook - a Limris, which I've previously singled out as the most original and entertaining contribution in the entire bestiary. The creature has been in cahoots with a leading Merikii Duke of Daryna, so in the aftermath the PCs are either going to accept a mighty bribe to stay silent about the Duke's involvement in kidnapping, slave labour and monster-wrangling or else set out to bring the villain to justice. Don't mess with the Merikii All of which is to say, this is A Very Fine Scenario Indeed. It could comfortably fit into two sessions but it might expand to more if the Referee expands on the aftermath. It's nice to see Merikii rather than Higmoni as antagonists (although the poor old pug-faces turn up here as well as thankless monster mooks). It's a bit more challenging than The Vemora or Tales That Dead Men Tell, offering situations and dilemmas that will put more experienced players through their paces. And yet, it falls short of what it needs to be. Kibbe takes a pride in modest threats: all three scenarios for Forge are self-consciously low-key affairs: no demons, no powerful mages, no dragons or vampires, no ancient curses or powerful relics. In this scenario, the main monster, the Limris, dies offstage - like the non-appearance of the Cavasha in The Vemora and the absence of scheming Maria Yates in Tales That Dead Men Tell. Kibbe seems to delight in creating big melodramatic plotlines and then locating his scenarios in their shadow: the players hear about but never get to meet the fantastical fiends. Yes, there's a pleasure in this sort of approach - like the 1994 "Lower Decks" episode of Star Trek Next Generation. The problem is that this sort of subdued, tangential narrative is all Kibbe ever produces. It's a bit like watching Rosenkrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead without having seen Hamlet - you haven't seen the real thing of which this story is the artful deconstruction. After three modules, we still don't know what a proper Forge scenario is supposed to look like, what the game has to offer when taken at face value. I would happily referee Amnesia as an introduction to Forge for experienced players - and it would convert very easily to D&D or other classic Fantasy RPGs - but it just isn't the sort of scenario that this product needed to sell the rather opaque 'Five Kingdoms' to an increasingly sceptical fanbase. Overall - how should we look back on this? Of course, Forge Out of Chaos passed away and this was its last gasp. Probably, the writing was on the wall for Basement Games back in 2000, but perhaps Mark Kibbe was sincere in his hope for further support for the game. But, no: Ron Edwards (2002) analysed 'fantasy heartbreakers' like Forge as doomed from the start by economic realities as much as by their shortcomings as products in a crowded marketplace. I'm glad, though, that Forge got this far and that Mark Kibbe was able to deliver his RPG vision. There is much to commend it, but it illustrates an important lesson in creativity: focus. Kibbe never seemed to grasp what was distinctive about his game or his setting. Forge clearly began life as a post-D&D homebrew that reached an unusual level of sophistication and completion. Kibbe himself moved away from conventional dungeons and monster-baiting, in favour of more thoughtful scenarios. His setting moved away from a barbaric post-holocaust world to a civilised but precarious frontier, with hardy colonists carving out their prosperity in the midst of a vast wilderness. Yet he failed to capitalise on these features. The Church of Enigwa, which goes around burning wizards as infidels ... a world where the gods have been judged and condemned .... a society built around trade routes and trade wars ... a system of travel documents, official permits and bureaucratic paperwork ... guilds and thieves rather than monsters and demons ... This is not like a standard Fantasy RPG setting, yet all this stuff is hidden away in the margins or must be inferred by a diligent reader. There's a good campaign to be had in Juravia, something distinctive and distinctively American, but you feel that, even at the end of the product line, designer Mark Kibbe hasn't quite figured out what it is yet.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed