|

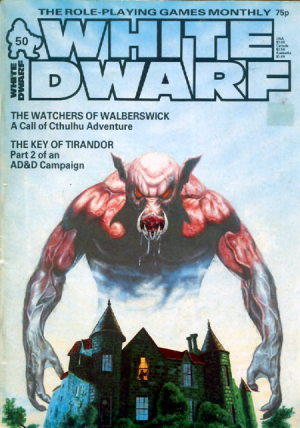

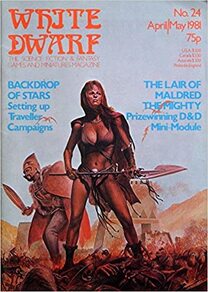

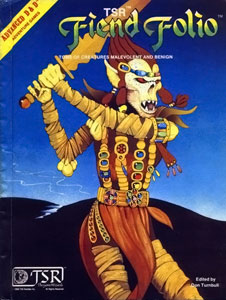

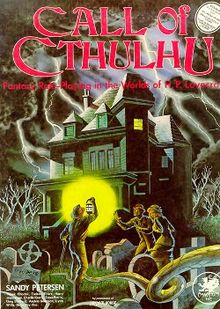

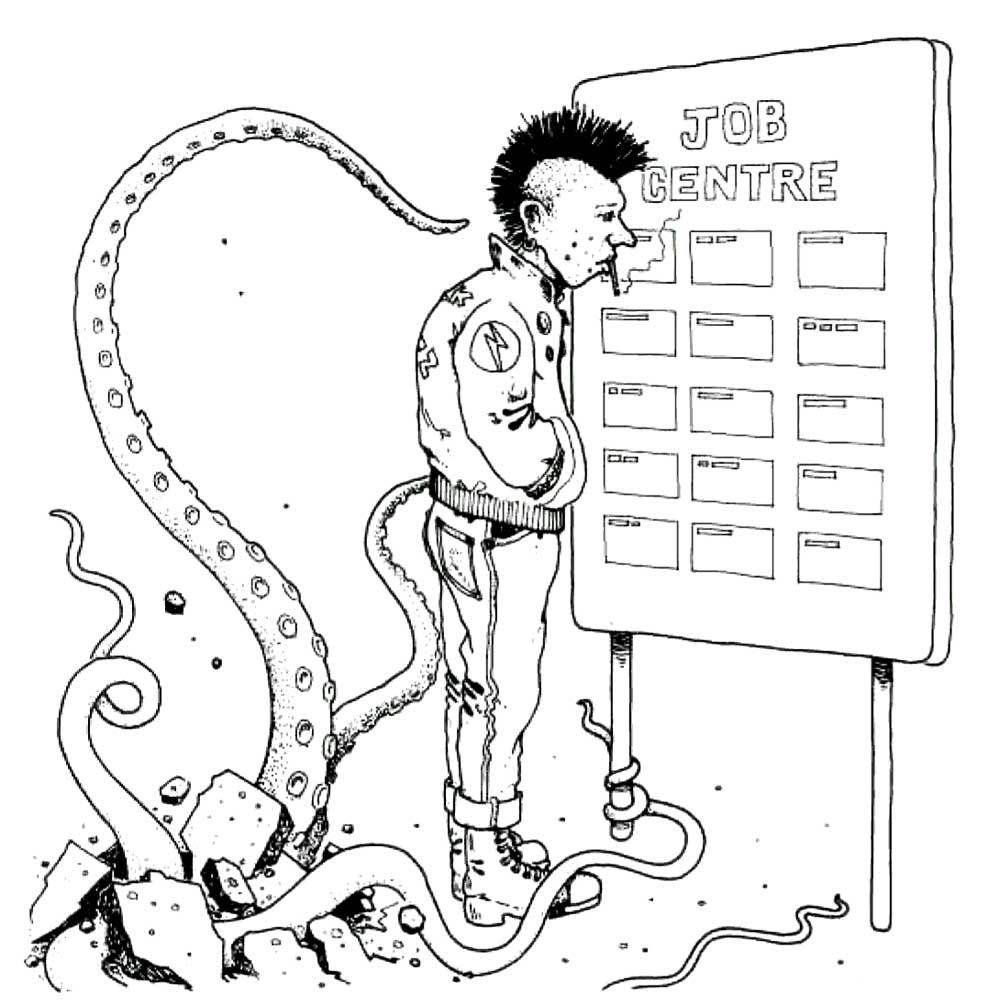

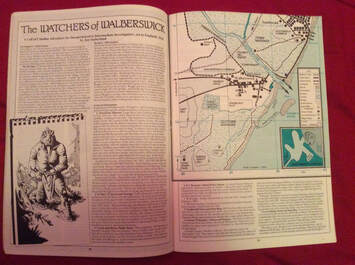

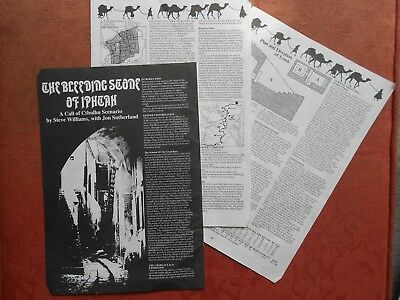

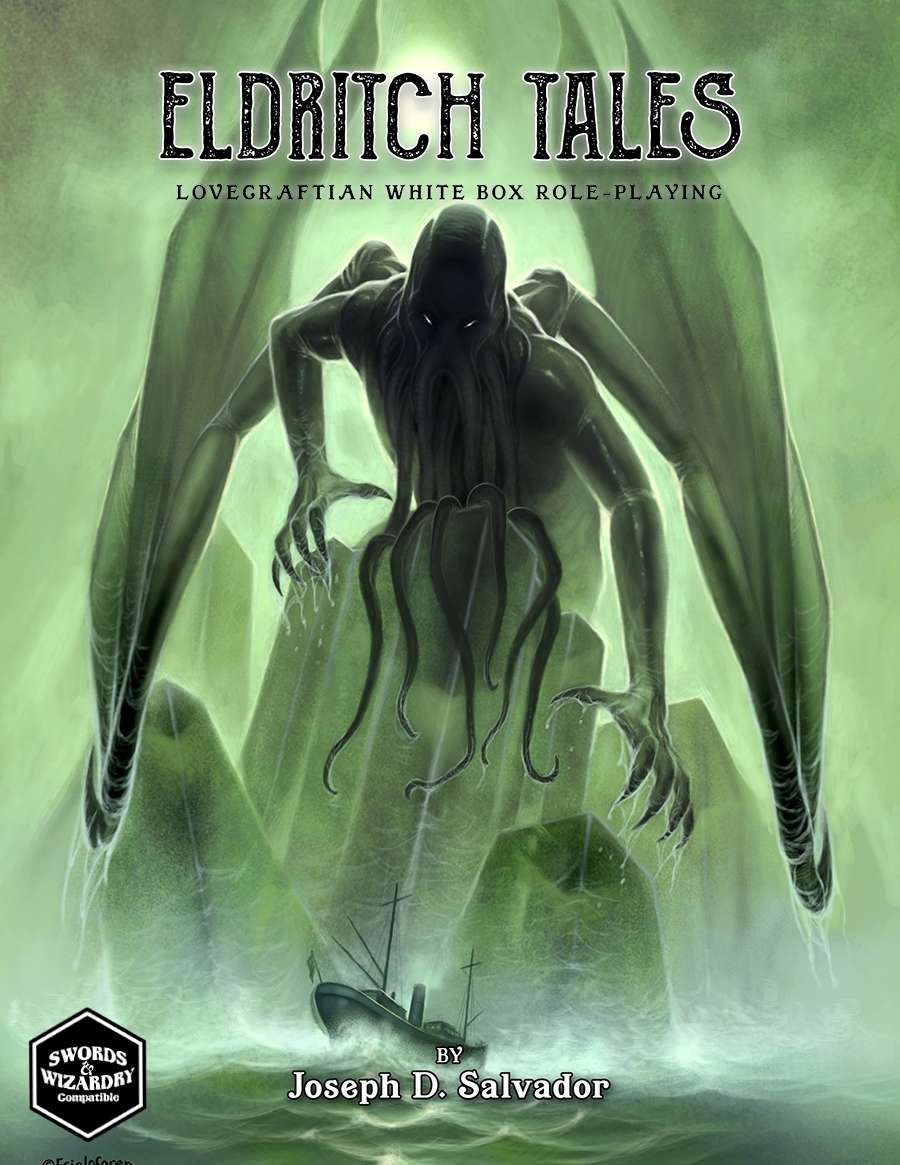

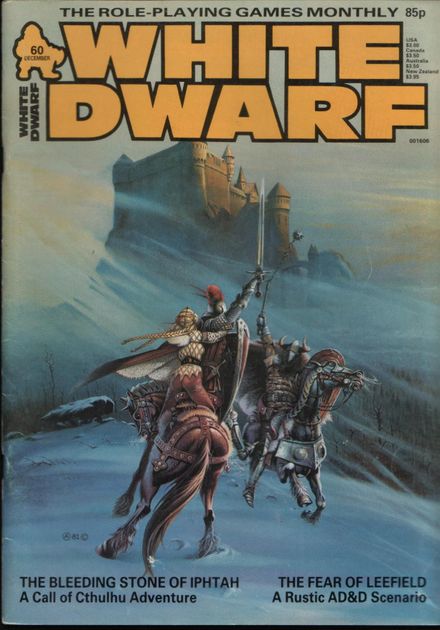

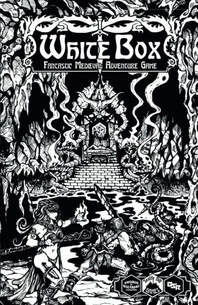

Back in the early-1980s, White Dwarf became the premier magazine for the roleplaying hobby. In America, Dragon reigned supreme in its support for D&D, but White Dwarf covered the whole hobby (more or less) and was unequalled for the quality of its journalism and contributions. There really were some fantastic scenarios for D&D and Runequest in particular, a brilliant column by Andy Slack supporting Traveller, a bestiary feature that inspired most of the AD&D Fiend Folio and great articles on campaign design generally. My favourite issue of White Dwarf (24) and the Fiend Folio, a sequel to the AD&D Monster Manual containing a mixture of monsters from TSR modules and the pages of White Dwarf. All things must come to an end and as White Dwarf moved into its 50s (in 1984) there was a perceptible dip in the imaginative temperature. Don't get me wrong: there were still some cracking scenarios to be published and most issues had a solid article or two, but it stopped being groundbreaking. The RPG companies were getting into gear supporting their own products with increasingly thoughtful modules and campaign settings. There was just less for a magazine like White Dwarf to do. Perhaps also, less consensus in the hobby over who it was primarily for. Ultimately, White Dwarf would turn into a showcase for Games Workshop's own products, but that was still a few years down the line. There was life in the old dog yet. One promising sign of continuing relevancy was a trend for scenarios for a new RPG: Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu, now a mighty industry behemoth but then a quirky outlier in the gaming constellation, pitching a roleplaying experience of dread, futility and, ultimately, madness and death in the world of H P Lovecraft's distinctive American Gothic. Call Of Cthulhu had been reviewed back in White Dwarf 32 (1982), with reviewer Ian Bailey clearly as impressed by the game as he was perplexed by how to make use of it (a common response at the time). He also observed that the game was "U.S. orientated and consequently any Keeper ... who wants to set his game in the UK will have a lot of research to do." The original Call Of Cthulhu RPG (the best cover too) and the White Dwarf issue that reviewed it - along with an excerpt from Ian Bailey's review Of course, since this was the Golden Age Of White Dwarf, it only took 10 issues for hobby maestro Marcus L Rowland to appear in the magazine, offering 'Cthulhu Now! - Call of Cthulhu in the 1980s.' The article grounds itself in an early '80s setting with an illustration of a punk studying a Job Centre noticeboard while a tentacled gribbly writhes up behind him! A follow-on article offered three contemporary scenarios: Dial 'H' for Horror, Trail of the Loathsome Slime, and Cthulhu Now! This opened the floodgates for White Dwarf contributors to submit a range of Call of Cthulhu material, including Cthulhu in space (The Last Log, by Jon Sutherland, Steve Williams and Tim Hall, from issue 56 in 1984) as well as Cthulhu in rural 1930s England (The Watchers of Walberswick by Jon Sutherland, from issue 50 in 1984) and Cthulhu in British Mandate Palestine (The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah by Steve Williams and Jon Sutherland, from issue 60 in 1984) . You'll notice Sutherland's name recurring? He was quite prolific in 1984! These early scenarios are typical for White Dwarf: they are concise but erudite, with a close attention to period and setting; they are thoughtful affairs, far removed from the pulpy excesses of Chaosium's own globetrotting campaign packs (like the epic Masks of Nyarlathotep, also from 1984 and closer in tone to a Bond movie than a Lovecraft story - a really good Bond movie spliced with Indiana Jones but pretty far from Lovecraft's cerebral interests). I suppose Jon Sutherland's efforts were attempts to take Call Of Cthulhu by the horns and deliver a narrative experience that feels like it really could be a horror short story by Lovecraft himself: very low-key but also, whatever their ostensible setting, very British. All this preamble is the context for me blowing the dust off White Dwarf #60 to run Sutherland's The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah on a group of three players over two evening sessions. Why pick this scenario? Well, it was used as the final scenario in the 1984 Games Day official Call of Cthulhu Competition and the introduction boasts that it provides "an interesting one-off session or addition to an existing campaign" - which sounds ideal for my needs. Next, the question of which rules set to use? That might sound odd, but post-CoC rules have proliferated recently and my respect for Sandy Peterson's imaginative achievement with Call of Cthulhu is only matched by my distaste for CoC's rules themselves, which are Chaosium's Basic Roleplaying system, with the addition of a diminishing Sanity (SAN) stat that spirals down to nothing as the Elder Nasties emerge. Lots of skills expressed as percentages, professions defined by skills and a lumbering combat system that manages to simultaneously make player characters too flimsy (any Mythos monster will squish them) and too tough (you have to shoot or stab someone several times before they fall down). The two contenders to replace CoC are Paul Baldowski's The Cthulhu Hack and Joseph D Salvador's Eldritch Tales. You can find both on drivethrurpg, but Cthulhu Hack is also available from the nice people at Zatu I've written about Baldowski's Cthulhu Hack before and, like most Hack games, it's great for pick-up-and-play. There are only two problems. One is that it tends more towards the pulpy action-adventure side of the CoC congregation and the other thing is that its Hack-derived mechanics don't greatly resemble classic CoC at all; both are problems for adapting the reserved tone and low-key assumptions of Sutherland's CoC scenarios. No, Salvador's game is the one I choose for this. For those who don't know it, it bills itself as Lovecraftian White Box Roleplaying. This means it takes the bare rules and conventions of Original D&D, especially the iteration known as White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game by Charlie Mason. Now, I fell in love with White Box when I attempted a long D&D-style campaign during 2020's Lockdown, so I'm excited by this. Mason's White Box is free (FREE!) on drivethruprg but a physical copy is stupidly cheap on Amazon too Eldritch Tales is a beautifully presented indie RPG product with evocative (and pleasingly amateur-style) art, fantastic layout, a delightful overview of the Lovecraftian milieu and careful explication of the (essentially simple) rules. Only the presence of a much-needed index would complete my bliss! The game invites you to create characters by rolling 3d6 for the classic six characteristics (Strength, Dexterity, Wisdom, etc.). Non-combat 'Feats' are attempted by rolling a d6 and you succeed on a 6 if your relevant characteristic is low (6 or less), on a 5-6 with ordinary characteristics and on a 4-6 of your relevant characteristic is 15+. Having a particular skill either adds +1 or +2 to the roll or lets you roll twice, choosing the best score - or sometimes both. So much better than faffing around with percentage dice. There are four character classes: Antiquarians, Combatants, Opportunists and Socialites. Within your broad class, you also roll or choose an Occupation that might give you particular skills, funds or possessions. Your Character Class gives you a d6 Hit points at first level (d6+1 for those hardy Combatants). Most weapons do a d6 damage (d6-1 for a thrown knife, d6+2 for a shotgun). Yes, every exchange of violence is potentially life-ending, especially as going up a level usually adds just +1 to your Hit Points. The levels only go up to 6th by the way. I think if your investigator gets to 6th level (with usually 3d6+1 HP), you should interpret that as the universe telling you not to push your luck any further. Insanity is a score that goes up during nerve-wracking encounters. If it ever gets to the level of half your Wisdom you gain a permanent insanity and if it ever matches your Wisdom you become a gibbering NPC. There are short-term shocks for people who fumble their Insanity saving throws (roughly 10% of the time) or gain 3 Insanity in one go (not that uncommon either once gibbous entities come calling). Two nice features of Eldritch Tales are the tables to roll up your Contacts (you have quite a few of these) and the table to roll up your Character Relationships. There are 20 of these suggestions, ranging from 'You are in love with another character (or their spouse or sibling)' through to 'You and another character witnessed something astounding.' These are so helpful for turning a bunch of numbers on paper into a team of investigators ready to risk life and sanity to investigate eldritch mysteries together. Past that point, Eldritch Tales is old-skool D&D: you roll saving throws and roll to hit Armour Class, there are familiar spells and monsters from the Mythos, you gain experience points from defeating the monsters or solving mysteries, you go up levels. The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah by Jon SutherlandThe scenario kicks off in Jerusalem in the 1920s, a time when the Palestine Mandate was overseen by the British Empire. It's a fantastic setting to launch any story - so good in fact that Kenneth Branagh (clearly also a fan of '80s White Dwarf) stole the idea to begin his recent film of Murder On The Orient Express. The PCs are Percy Goodfeather, a Gentleman Socialite who is searching for his vanished sister Darcy. He brings with him his university friend Howard Harris, an Australian Occultist Antiquarian: the two bonded when another friend disappeared, never to be seen again, during one of Howie's rituals in the college rooms. Percy's largesse helps fund Howie's growing drug addiction. They have been brought to Palestine by Joe Birdwell, an Opportunist Outdoorsman who knows the region and its peoples. Birdwell is secretly in love with Darcy Goodfeather, but he knew her as Dahlila de Gul, a torch singer and medium; he was an enthusiastic participant in her demimonde orgies until her strange disappearance. He has tracked her to Jerusalem, but not told Percy of his sister's double life. What's Going On? Actually, none of this is in Sutherland's scenario; these are incidents derived from Eldritch Tales' table of relationships and a few Tarot card draws to help brainstorm a plot. But I can tie it together

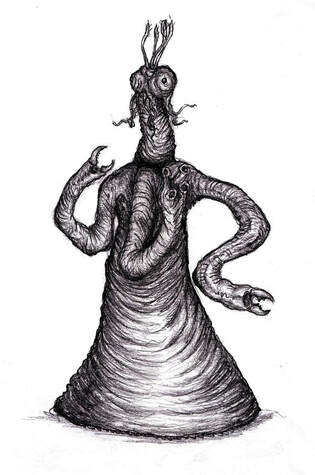

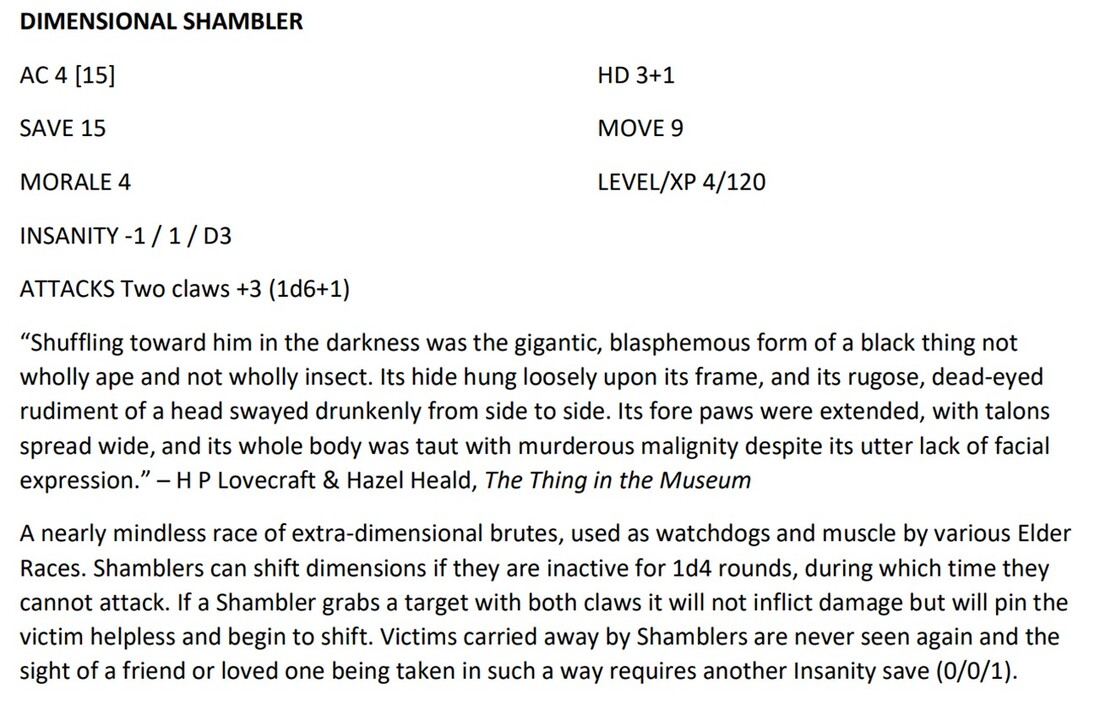

Start With Action The scenario starts with the PCs browsing a museum in Jerusalem when they are approached by a shifty Turkish gentleman named Lakey who wants them to take on a job for his boss, a businessman named Lotto who owns the Domino Club and is obsessed with antiquities. This is a run-of-the-mill CoC plot hook and the two NPCs are a delightful hommage to Peter Lorre's Ugarte and Sydney Greenstreet's Ferrari from Casablanca (1942). The sweaty grifter and the intimidating black marketeer Except that being led by the hand by a bunch of NPCs to a patron who explains why they have to go to a dig site in the Judean Mountains and chivvy along an archaeologist called Foster who has promised to bring back treasures for Lotto but has so far turned up nothing ... well, that's a slow start my friends. So instead we have Joe Birdwell see Darcy pass by in the street - and he jumps out of the window to give chase. Darcy is being stalked by dangerous looking Bedouins but when Joe reaches her she reacts without recognition. One of the Bedouins fires a gun at Darcy, but Joe is hit and Darcy takes off in a car while the street erupts in confusion. Percy and Howie arrive to find an Arab doctor treating Joe and warning them that the Bedouins were tribesmen or a cult called Pachalim (made up name but it'll fly) and very dangerous customers. A Side Plot Develops The PCs are supposed to take the job from Lotto and journey to the dig site at Iphtah, but my ad libbed side plot has taken over the story. Joe goes to find out more about the Pachalim from a contact - an Arab businesswoman nicknamed 'the Ibis' (for her pronounced nose). This vociferous widow with her melodramatic flights of insulting rhetoric quickly becomes one of my most beloved NPCs! Joe parries and feints and handles her beautifully and ends up shadowing a pair of Pachalim goons as they invade the seedy guest house where Darcy is staying. Joe gets knocked out when he tries to intervene but, waking as a prisoner of the Pachalim, learns that they are trying to stop 'the Forgotten' (almansiayn) from carrying out a ritual. Yup, they're the good guys. Joe is released, doped up with hashish, and stumbles home to the Domino Club. Percy and Howie have been pulling their own contacts, find out a lot about Foster and discover that the local gangs that Lakey buys drugs from have acquired new weapons in the form of Rot spells that do horrific things to their victims. When the three PCs visit Darcy's guesthouse the next morning, they find Darcy has moved on, but one of the Pachalim is there, dead from a Rot spell, and clues point to Iphtah where Prof. Foster is digging. Yes, this is me trying to re-direct things because this side plot has taken up the evening and we haven't even arrived at the location of the actual scenario. Journey To Iphtah The main scenario takes place at the dig site at Iphtah, where Prof. Foster is going mad. The Professor is using opium to keep the Yithians out of his head, but he's run out of drugs and thinks that Lakey (his supplier) is holding out on him. The PCs get to snoop around the site, spy on the erratic Foster and realise strange things are afoot, but this is a programmed scenario where the PCs have to be onlookers to certain events and no amount of roleplaying or researching will speed them up. In the middle of the night, Foster murders Lakey to get at the drugs, then overdoses himself. The PCs manage to stop the truck escaping with Lakey's corpse by shooting out a tyre. They are left at the dig site with no Lakey, no Professor but a mysterious red stone - the Bleeding Stone of Iphtah. This is where it gets creepy, because a bunch of Dimensional Shamblers show up if anyone tries to remove the Stone from the site without performing the ritual. I hide the Shambles in an eerie dust cloud (for extra creeps) and use them as silent sentinels who murder the Arab labourers to establish their monster bona fides but otherwise leave the PCs to explore. There's a buried shrine to be found and opened and the Stone has to be 'bled' inside a pit to power up the ritual and then ... err .. and then ... ah, well, that's about it really. The PCs are free to leave. Perhaps suspecting that things could turn out rather anticlimactic, Jon Sutherland suggests a raid by snooping Bedouins and I've already set up the Pachalim for exactly this sort of work. The PCs end up stuck in the shrine with the Pachalim outside with rifles in a tense standoff. Then Howie the Antipodean Antiquarian leads the charge, shoots the Pachalim sheikh dead, but is riddled with bullets himself. Percy and Joe shoot their way to safety and the Shamblers disembowel the fleeing Pachalim. Percy and Joe get to leave the site, supervised by the silent Shamblers. And that's, kind of, where it ends. The scenario doesn't make it clear just how the ending is supposed to go down. My players decide to return the Stone to Lotto and continue their pursuit of Darcy. They are unaware of the role they have played in facilitating the arrival of the Yithians by performing the ritual. Evaluating the Scenario and Eldritch TalesThe Bleeding Stone of Iphtah is a rather slight affair. In fact, all of Jon Sutherland's 1984 scenarios are oddly muted. I think they were written in deliberate contrast to the gangbusters style of American CoC material, to be atmospheric, unsettling and cryptic, rather than kinetic, deadly and cosmic in scope. In all of them, the Mythos is a marginal force, largely operating off stage. The PCs spend most of their time exploring a realistic but evocative location, then at the very end there's a Mythos intrusion. The central problem is that there's no way for the PCs to understand the significance of what's been going on or their role in it. Now, in an ongoing campaign this is acceptable - further down the line, the PCs might uncover information which casts a revelatory light on the goings-on at Iphtah and realise that, by performing the ritual, they brought the Yithian-apocalypse a dread step closer. They might then understand why Foster was taking drugs and why the Shamblers appeared to stop them leaving with an un-bled Stone. But as things stand, there's no way to learn any of this - and this was a scenario, you will recall, billed as "an interesting one-off session or addition to an existing campaign." One wonders what the contestants at Games Day '84 made of it. I know some people will retort that Lovecraftian roleplaying is supposed to be mysterious and it's a good thing, not a bad thing, if a scenario leaves players puzzled and disquieted. Yes, that's true, I suppose, but my taste is more for a scenario that places the players in positions of at least partial knowledge. Too much of Iphtah was meaningful only for the GM, even with my improvisations. But these are minor gripes and I should perhaps essay another Sutherland scenario - perhaps the well-received Watchers At Walberswick - before forming a judgement on his output. Eldritch Tales served us very well and is now my go-to RPG rules set for Coc material. I was pretty generous in handing out experience points for roleplaying (and why not? the roleplaying was stellar!) and of the two characters who survived, Percy reached second level (losing some Insanity and gaining that precious extra Hit Point) with Joe just missing his level-up. I'd love to dust off a larger campaign pack - perhaps Shadows of Yog-Sothoth - to run using Eldritch Tales. However, I became very aware of how flimsy Eldritch Tales PCs are compared to CoC: every gunshot or knife wound is potentially lethal. Perhaps swashbuckling Cthulhu Hack would be a better fit for those pulp-y Chaosium campaigns? But for the studious and low-key Call Of Cthulhu scenarios that White Dwarf and Jon Sutherland were publishing in the mid-1980s, Eldritch Tales is ideal.

0 Comments

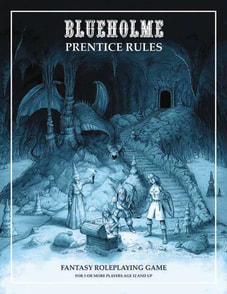

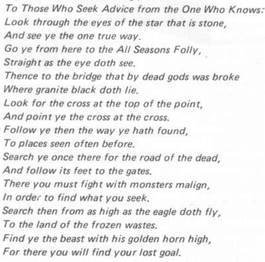

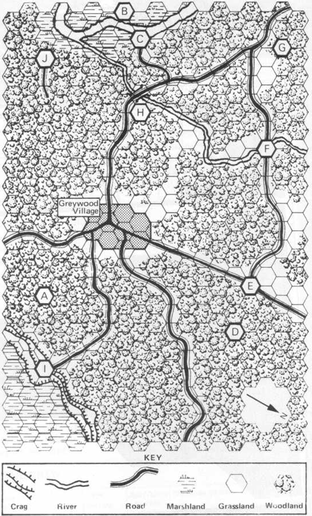

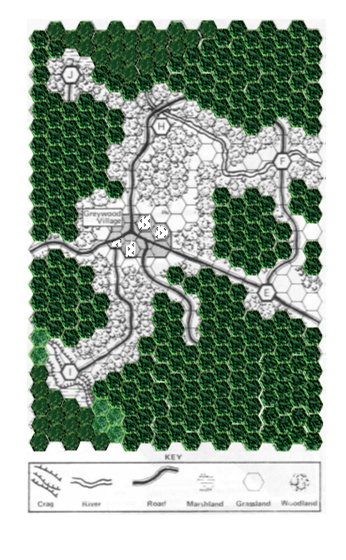

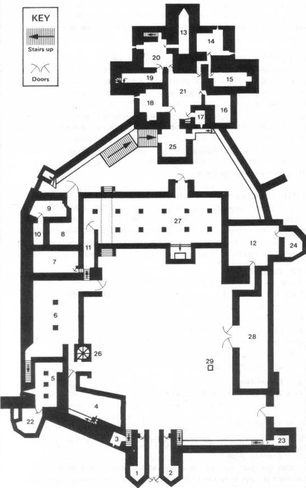

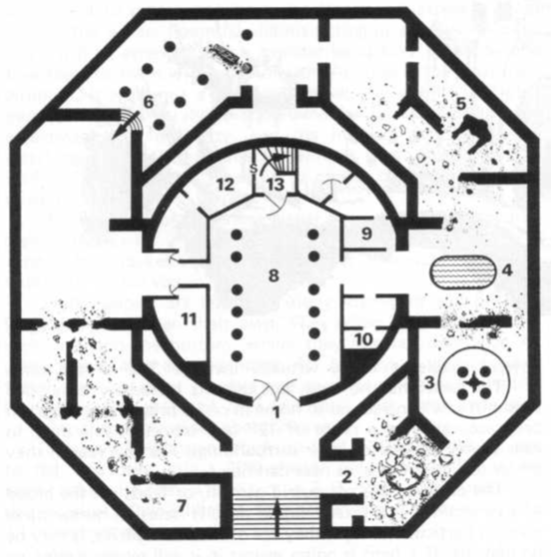

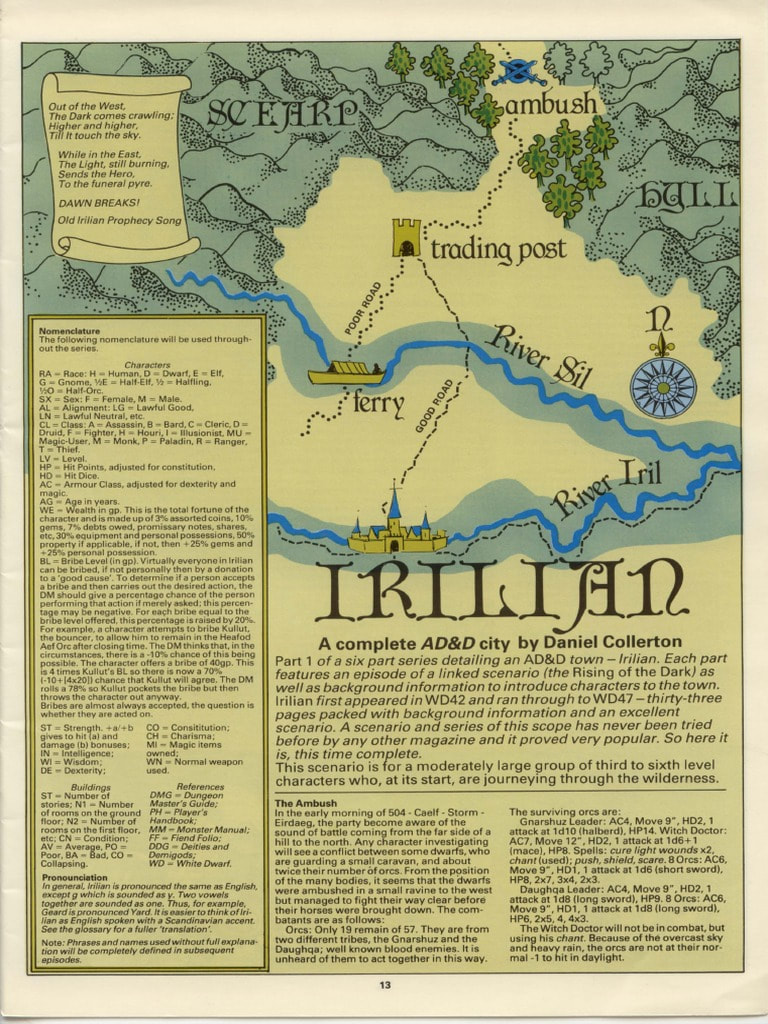

Like a lot of people, I like to celebrate my birthday by getting friends together for a game: either one of those big brainy wargames like Dune where everyone ends up in the kitchen, plotting, or else a jolly, feel-good RPG session, a sort of festive one-shot. Covid Lockdown imposes constraints on both activities, but the wargame more than most. So we gathered this afternoon to play old school D&D: five players and myself, talking through Zoom, rolling dice on Hangouts and me showing maps and floorplans by sharing a PowerPoint display. But what adventure to run? I'm time-pressed, right ahead of returning to work tomorrow, so it has to be a pre-made module. Time to dust off one of those old classics from the glory days of White Dwarf magazine. My eye falls on Barney Sloane's The Search for the Temple of the Golden Spire from White Dwarf 22 (1980). You can also find this mini-module in Best of White Dwarf Scenarios II Barney's adventure had always been a favourite of mine, although I'd never run it. How would it stand up, after all these years? I think, back when I was 13, Golden Spire impressed me immensely. This was no underground maze or skirmish in a fortress. Barney set out an attractive wilderness map extending around the village of Greywood, complete with ruined towers, Cloud Giant lairs, talking trees and a forest full of gnomes and sprites. There are two mini-dungeons to encounter. There's a riddle that serves as a coded map to guide players from one end of the wilderness to the other, culminating in the eponymous Temple where some very hardy monsters reside. The whole thing has a folkloric, faerie atmosphere that appealed to me greatly (and still does), brewing up elements of Spenser's Faerie Queen with its forest in which big evil temples pop out of the landscape and queer woodland folk offer cryptic clues. Remember, this was only 1980. This sort of above-ground adventure in an atmospheric wilderness setting was quite novel. B2 (The Keep on the Borderlands) only appeared the previous year and the wilderness segment of that was only a prelude to the real business of clearing out the Caves of Chaos, one goblin at a time. Usually, wilderness was just something to cross in order to get to the adventure: here it was part of the adventure itself, along with a small town-based segment as well. Although Jean Well's B3 (Palace of the Silver Princess) contained a wilderness element and a similar faerie vibe, it was (in)famously recalled and rewritten; the next product I would find with this sort of integration of setting and adventure, Judges Guild's The Illhiedrin Book, was still a year away. If you're my age, your adolescence is defined by either these covers or The Clash's record sleeves. Rereading Barney's adventure, 40 years on, I can see some flaws. It occupies that strange twilight zone between Original D&D and AD&D: creatures from the AD&D Monster Manual are referenced, but this is a OD&D adventure through-and-through, with little or no reference to the Dungeon Master's Guide's rules for wilderness travel, for example. There are confusions and omissions. What's the scale of the map? How far can PCs travel? How often do you check for Wandering Monsters? More importantly: just why, exactly, are the PCs seeking the Temple of the Golden Spire? Nowhere does the scenario explain what it is or why anyone would want to go there. It's sort of assumed that, once a Celtic Cross expounds a riddling quest, adventurers will just rush off and risk their lives to fulfil it on general principle. Certain aspects of the riddle are unexplained and there seem to be crucial details missing from the description of Greywood: what is the star that is stone? what's the deal with the abandoned house? what exactly do the clerics know about the Temple? what's the deal with Greycrag Citadel, visible on the horizon? You get the impression that Barney didn't bother setting down on paper everything that was going on in his campaign setting. Nevertheless, this scenario inspired a host of imitators in the pages of White Dwarf who corrected his mistakes, even if they never quite capture the faerie charm of Golden Spire: Phil Masters' The Curse of the Wildland (#32 and exemplary, like most of Phil's stuff) and Paul Vernon's Troubles At Embertrees (#34) were both from 1982; Stuart Hunter's The Fear of Leefield (WD#60) from 1984 and Richard Andrew's prize-winning Plague from the Past (WD#69) from 1985; all did a fantastic job of sending the PCs from a village in peril, through a cleverly constructed wilderness setting to a micro-dungeon showdown, but with a tighter plot and closer attention to AD&D rules. The thrill I used to get as a schoolkid when these things came thumping through the letter box.... It's not a problem filling in the gaps in Barney's scenario. He seems to intend some clue in the stone cross to send the PCs journeying down the road to the east. I introduced an evil presence in dreams that was recruiting villagers to the cult of the Golden Spire and the disappearing peasants act as impetus to investigate and the PCs' own nightmares make the stakes personal: if they cannot locate the evil temple and destroy its power, they too will convert to Chaos. AD&D, OD&D or ... gasp .... Holmes ???1980 was an odd time for D&D. The AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide had just been published - I acquired mine for Christmas in 1979 so it's quite possible Barney Sloane didn't even own it when he composed Golden Spire, perhaps using only the AD&D Monster Manual and the Original D&D rules set for his campaign. That would explain the odd, eldritch tone of his adventure. Back in 2020 I ran a campaign using the wonderful White Box rules, which do a great job of capturing OD&D. In fact, there's a huge section of this website documenting my attempts to reverse-engineer lots of character classes into White Box's delightful 10-level world. I promised myself I'd next turn to Blueholme next to capture the flavour of the Holmes Basic Set. But for this scenario, I wanted to try something different: the Blue Hack RPG. Three brilliant OSR rules sets - click on the images for links to purchase: PDFs of White Box and Blueholme are pay-what-you-want and Blue Hack is under £2 Blueholme and Blue Hack are both by Michael Thomas of Dreamscape Design. Blueholme is a straight-up retroclone of the Holmes Basic D&D Set, but the recent Journeymanne Rules expand the game to 20th level, introducing all sorts of PC race options beyond the basic Elves, Dwarves and Halflings along with lovely OSR art. Blue Hack is a different proposition. In just 22 pages, it condenses the D&D experience in the same style as the groundbreaking Black Hack RPG. You roll your classic 6 abilities on 3d6: Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Wisdom, Intelligence and Charisma. No modifiers or saving throws; if you want to hit something, you roll under your Strength on a d20; dodge an arrow, roll under your Dexterity; spot a secret door, roll under your Wisdom. Your class offers you Hit Points and damage is based on your class, not your weapon. Going up a level grants you opportunities to increase your abilities (try to roll equal to or over them on a d20). Monsters with more Hit Dice than you impose a penalty to hit or dodge them. Armour soaks damage. Every spell gets a single line of description; same with every monster. That's it. The rest is up to you. Blue Hack offers a few Holmesian tweaks to the Black Hack formula, like racial bonuses for the obligatory Dwarves, Elves and Halflings; some Holmesian spells and monsters; some refocusing of character classes. Enough to make it feel like 'Blue Book' era 1970s D&D. The beauty of this is the sheer speed with which you get a character up and running. You might think it's fast creating a character for Basic D&D, but there are hardly any tables to consult in Blue Hack. If you're creating characters online, over Zoom, this sort of pick-up-and-play ethos is invaluable. Blue Hack also suggests that PCs gain a level after every session/adventure/encounter - whenever the DM likes, really. With Golden Spire I wanted the PCs to start at 1HD (1st level) and rise to 3HD (3rd level) by the time they entered the Spire itself. This proved very straightforward - at various points, players got to roll and add those extra Hit Points, check to see if any abilities increased and expand their spell slots. Beautifully simple. So, what happened? [SPOILERS]Character generation throws up the usual adventuring misfits. David is a cretinous dwarven halberdier named Dimples; Emily an elven thief named Gnashe; Alex an elven fighter-mage named Azure-Wall; Oliver a good-looking human fighter named Gomez; and Karl turns to the macabre with a child cleric named Bilge who worships the god of scarecrows and communicates through a sock puppet.. This bunch don't ask for motivation: they study the riddle and get on with the quest. The tone is larky and riddled with Monty Python-isms: the villagers export walnuts and take everything literally, arm-wrestling resolves most interactions, cultists complain about itchy robes, no one believes gnomes exist. Not wanting to waste Barney Sloane's excellent scenario map, I moved it into PowerPoint for screen-sharing and covered the hexes with terrain-themed shapes, then deleted each shape as the party moved through the wilderness, revealing the map below. This was such an effective way of revealing a map and dramatising exploration, I'd love to do it for a round-the-table game, if such a format ever resumes. Yeah, you can probably do something similar on RollD20 ... The party discover Greycrag Citadel, infested with kobolds. It's a lovely castle map that I'll definitely re-purpose for future games. In this case, Gnashe sneaked in alone, found the viewpoint from the tower from which the Golden Spire could be located and the party covered her embattled retreat, chopping down kobolds and ghouls. Greycrag and the Temple of the Golden Spire: aren't those lovely? White Dwarf always excelled at scenario maps Heading to the Spire, the party have fun with wandering monsters: Yorkshire Centaurs and an Ogre teaching his son how to devour humans (feet first, of course). By the time they reach the evil temple, everyone is 3HD/3rd level and pimped enough to take on hard monsters, like a Harpy and the climactic Wraith (who of course drains several people of their levels before being pelted to death with the harpy's trove of silver coins). I decided that the introductory riddle was in fact sent by the Wraith, to lure the party to the Golden Spire and trick them into freeing him from his prison. It's a feature of Barney Sloane's old school scenario construction that, in his version, there's no explanation given for the presence of various monsters in the Temple of the Golden Spire: they're not doing anything, they're just waiting for adventurers to turn up and attack them. However, to his credit, Barney's kobolds in Greycrag Citadel are a fairly dynamic bunch, busy getting on with all sorts of interesting things when the PCs turn up: roistering in the big hall, torturing prisoners, sleeping on guard duty. That's another example of this scenario from 1980 being a sort of half-way house between the aesthetics of Original and Advanced D&D. Later, more sophisticated scenarios in White Dwarf in the '80s, by people like Phil Masters, would give careful thought to the presence of every monster and use them all in the service of an overall plot or theme. Overall, can Blue Hack really hack it?Blue Hack was a big success for this sort of level-up-as-you-go scenario. I'd love to use it for some of the old TSR Modules: Tomb of Horrors, maybe? or White Plume Mountain? Or dust off some later, more complex White Dwarf adventures, like Daniel Collerton's fabled Irilian city/campaign (WD#42-47). I'm not sure Blue Hack would serve for a conventional campaign. The roll-against-your-abilities system means that characters with high Strength or Dexterity will rarely miss - or get hit - in combat, even against tougher monsters. For example, with Strength 17, Dimples the Dwarf was hitting monsters with the same HD as him 80% of the time. How many 1st level characters in ordinary D&D have those odds? Without Armour Class, monsters enjoy some protection from damage, but a party of PCs can pile on the damage quickly, ending fights in just a round or two. Now, I quite like that - nothing is more boring than one of those OSR D&D fights that just goes on and on - but a sense of peril is lacking, especially as being reduced to 0 HP only has a 1-in-6 chance of killing you assuming the rest of the party survive to rescue you. The other feature is that, without experience points being needed to level up, PCs have no motives to seek out treasure. You might feel that's a good thing too: let adventurers be motivated by more realistic concerns, like duty or honour or saving the realm or rescuing loved ones. But it's surprising the amount of D&D material that's predicated on treasure as a motivator and if the PCs don't need to acquire it, all sorts of scenarios, traps, dilemmas and rewards need to be re-thought. Of course, you could easily paste a basic XP system onto Blue Hack to restore that mercenary motive. I think Blue Hack will be my system-of-choice for D&D one-shots, especially re-vamping old scenarios. It fast set-up and rather abstracted combat system makes it ideal for online RPGing. I like the fast fights and the option to assign level-ups at dramatic moments, rather than tracking XP. Its lack of 'grit' or peril might be a drawback, but it offers a fresh perspective on those old-school modules and scenarios. Did somebody say C2: Ghost Tower of Inverness? Let's go get that Soul Gem!

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed