|

In a previous post, I analysed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic, used by the worshipers of Grom and Berethenu. This led to details about Forge's odd mythology (these are the only active deities and both are imprisoned in the subterranean fiery hell of Mulkra) and Ron Edwards' observation that it is typical of 'fantasy heartbreakers' to belabour mythological backdrops but ignore the role of religion. To be fair, of all the heartbreakers that he reviews, Edwards concedes that "the best of the bunch is Forge: out of Chaos, probably (as I read it) because this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." Edwards sketches out a brief checklist of the way these games travesty religion while obsessing over mythological settings:

Let's see how Forge measures up to the first two; the third will have to wait until the next blog. The God-Wars The Forge rules open with a mythological treatise, explaining how the Supreme Being (named 'Enigwa') created the world and ordered it to be beautiful and harmonious. Enigwa then snoozes (having become Enigweary?) and his children, the gods, are left in possession of the paradise he has bequeathed them. The gods start off perfect too, but they become more differentiated as the ages pass, with some developing selfish or aggressive traits. The Supreme Being is disturbed by this discord and, I suppose, Enigwakes. He draws the gods together in fellowship to create Humanity and then commands the gods to be mankind's instructors and guardians, for Man shares the best and worst traits of the gods. Then Enigwa disappears, off to create new worlds (his Enigwork?), strangely blind to the trouble he has set in motion. The gods immediately fall out and a triumvirate forms: Necros the god of Death teams up with his brothers Grom the god of War and Galignen the god of Disease. Grom starts creating his own servitor races by mutating humans: the orc-like Higmoni, the Klingon-inspired Berserkers and the one-eyed gorilla Ghantu. After a polite pause to register their shock at this impiety, other gods follow suit: Dembria, goddess of Creation, creates the albino Dunnar; Katharu, god of nature, creates the lizardy Kithsara; Marda, goddess of Animals, creates the avian Merikii; Omara, goddess of harvests, creates the half-pint Sprites; even virtuous Berethenu, god of Justice, creates his loyal Dwarves. I'm not sure who creates the wheezing weasely Jher-em; Marda, I suppose. The Elves aren't attributed either, but Terestar the god of Time appeals to me as their creator. The gods go to war, tearing up the landscape. Marda is particularly wrathful, creating monsters and Dragons to defend her pristine wilderness. Necros figures out how to create the Undead to be his creatures. He tricks Dembria into creating the moon to blot out the sun, so that his undead army can dominate the lightless world. Then, when his sister Shalmar the goddess of Life pleads with him for peace, he murders her Enigwa returns to judge his creations and he isn't happy: his Humans have been mutated into other races, the landscape churned up and rearranged, Shalmar dead, the moon blocking out the sun: it's not pretty and the Supreme Being is Enigwrathful. He pronounces judgement on Necros, flinging the death-god into "the endless void." Grom gets dropped into the fiery depths of Mulkra for his crimes. Berethenu has the chance to repent but is too noble to accept forgiveness: he leaps into Mulkra to be imprisoned with Grom. Enigwa gathers together the remaining errant gods and takes them away with him, leaving the world of Juravia to recover from this divine ruckus. The various races are left to pick up the pieces in a god-free world. They reconstruct the principles of magic but, since these powers no longer come directly from gods, Pagan Magic is uncertain and has nasty side-effects. Down in Mulkra, Grom and Berethenu seize moments between burning in eternal agony to invest their worshipers - Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors - with Divine Magic. There are rumours that the gods occasionally sneak back to Juravia when Enigwa isn't Enigwatching and the monsters and undead horrors unleashed during the Great Wars are still out there, causing trouble. All this rationalises a fantasy world with monsters, races and magic, Dumb Names Guilty as charged, but it's not all bad. If Enigwa is a dumb name for the Supreme Being then chain me to the wall. It's got 'enigma' in it but the W has been flipped, see? The overall effect hints at something African, which is great. There are a lot of GFNs (Generic Fantasy Names), just syllables with -a or -ia or -ar added on the end. 'Necros' is lame, being filched from the Ancient Greek nekrós meaning 'corpse.' I'm sympathetic to the Tolkien Conceit, that fantasy names are just translations into familiar English of words that are really in other languages, so Peregrin Took was really "Razanur Tûk" in Westron. But if you're going to do that, be consistent. Shalamar should be named after the Greek for 'life' which is Zoe, Grom should be Polemos, Galignen should be Nosos and Marda should be Therion. Fine names all. Some of the names have a whiff of poetry to them. Galignen has connotations of 'malignant' which is clever. I like the -u names Berethenu and Kitharu, which suggest (to me) something Babylonian or perhaps Romanian or East Asian. Grom is a near-steal from Robert E Howard's Crom, the war-god Conan respects (I was going to say 'worships' but that's going a bit too far), and in turn adapted from Celtic myth. But it's all a mad jumble really and not in a good way. Over on Zenopus Archives, there's a 'Holmes Random Name Generator' that creates fantasy names extrapolated from the quirky imagination of Basic D&D author Eric Holmes. These names may be random but they're not GFNs: Chor Paldon, Zoque Kar, Losho the Blue, I could do this all day. Try it yourself: These names are random collections of syllables, but they're still evocative. Crucially, they're not European in flavour. They sound like they're from a slightly alien fantasy land: not Marda but Mardreb, not Dembria but Drebael. Thomas Wilburn slams Forge for (among other things) starting off with 10 pages of myth-making before we get a content page, never mind rules: "mythology belongs in a background section in the main text, not at the very front where the reader has to wade through it just to get to the game." But the trend for '90s RPGs to kick off with thematic fiction or campaign setting before introducing the rules was well-established long before Forge came along. No, I don't object to the positioning of mythology at the start of the book and it's well-written: in fact, it's the best-written part of the whole book. I just wish the Kibbe Brothers had knuckled their foreheads and come up with names that were genuinely evocative or thematically consistent . What cultural setting do these deities connote? Five minutes of Google-fu (or half an hour with a decent encyclopaedia) prompts suggestions like this: This harmonises the gods' names (I like that -u ending and -ara as the feminine suffix is more interesting than plain -a or prettified -ia) and Nergu re-names Necros along Babylonian lines. Just sticking an O- prefix in front of Grom works wonders (and connotes 'ogre'). Why would all the races use the same names? The creatures of Kitharu and Mardu get a synthesis of Babylonian and Yoruba names and the 'Grom-folk' (Higmoni, Berserkers, Ghantu) get Japanese-inspired adaptations. I think the Dunnar would have Celtic-style names (reverencing Dembara and Dobuna, Berethenu as Berethos and Grom as Crom) and let's go with Norse-style for the Dwarves (re-titling Berethenu as Borothor and Grom as Grotun) and Greek-style for the Elves (Berektor and Grotos). Names do amazing things: they imply a world. Un-fun Strictures No surprises here. Grom Warriors and Berethenu Knights both have to follow an honour code. For Grom-ites it's a simple barbaric code of never running away, fighting face-to-face and taking part in a demented yearly rally. Berethenudians have a chivalrous equivalent that gets more restrictive as they advance: eschewing armour and fighting fairly. From a roleplaying perspective, these strictures are intensely external to your character's identity. It's frustrating for Berethenu Knights that they cannot wear plate mail and have to give away a tithe. Not being able to attack from behind makes a few combat encounters slightly more awkward than they have to be. But you can 'tick the boxes' with these requirements and play your cleric just like all the other characters. What we don't learn is what foods are forbidden, what clothing must be worn, what sex acts are condemned, what daily rituals must be enacted. In other words, what is like to live in the service of this god?

The oddity is not that clerics suffer such strictures, it's that no one else does. There's a tendency for lay people to adopt the strictures associated with holy folk in order to make their own lives more holy. Over time, these strictures become the sort of codes of dress, diet and sexuality that make up a religious lifestyle. If Berethenu Knights tithe and behave chivalrously, then this sort of chivalrous, charitable code will spread to other people who don't have magic powers to lose. If Grom Warriors fight one-on-one and boast of their kills, then a culture of dueling and boasting will also become normative in society. One way of handlig this is through Benefits & Detriments (pp17-18), which currently involve trading of advantages (being tall or stocky or having a resistance to poison) against drawbacks (arachnophobia, deafness or being one-eyed). Religious strictures make good Detriments and violation can be punished by removing experience checks or imposing bad luck (-4 on next Saving Throw). It's interesting to reflect on what else Grom or Berethenu expect from followers. Are Berethenudians vegetarians or virgins? Or are they expected to marry and have families? Are Grom-ites forbidden to marry or acknowledge their children? In the real world, sexual abstinence is the distinctive feature of religious observance yet it gets no mention in RPGs like Forge. Distinctive dress codes and grooming are features of real world religions: Jewish peiyot (side-curls) and kippah (circular head coverings), beards in Islam, turbans in Sikhism, bindi (forehead dots) in Hinduism and Jainism. Often, these create a more abiding stereotype of a religion than anything the members actually believe or do. How does one recognise a Berethenu Knight? Do they wear sashes, turbans, shawls or phylacteries? Do Grom Warriors shave or wear hair down to their knees? Of course, to answer these questions, you need to have a cultural conception of the fantasy world these people inhabit. Is it Northern European, Middle Eastern, Asian or African in tone? In order to decide whether Berethenu Knights wear turbans or kilts, you need first to consider what sort of ethnicity they represent. Unsurprisingly, the Forge art represents 'Humans' as white Europeans (e.g. p12, p86, cloak, trousers, cean-shaven, mullet). That's disappointing (and not just because of the mullet) and it will take another blog to explain why.

This leads into the most important topic, which is how a fantasy world is shaped by its religions - a point widely ignored in games like Forge - and I'll get stuck into that in the next blog.

0 Comments

It's time to take a look at Forge's magic system. This is the only aspect of the game to attract universal praise. Ron Edwards identifies the magic system as "genuine innovation" and even Thomas Wilburn (who hates the game) admits that " the game has an excellent way of dealing with high-powered wizards." Forge splits magic into two broad types: Pagan Magic (aka Sorcery) and Divine Magic (clerical stuff). In fact, all the magic is ultimately divine in origin, being passed onto lesser races by the gods. The difference is that Divine Magic is still a direct gift of the remaining (albeit imprisoned) gods, while Pagan Magic covers mystical forces that mortals have learned to master without the gods' ongoing assistance. When you sink those 10 skill slots into the Magic skill, you must make a decision: Divine or Pagan? This is particularly important for dimwit Ghantus, who normally have to spend twice as many slots to acquire any skill at all. Since Divine Magic is granted directly by a god and doesn't reflect on the caster's own intelligence or education, Ghantus can learn Divine Magic for the standard 10 slots rather than a nearly-impossible 20. Let's take a look at Divine Magic this week. Knights of Berethenu and Warriors of Grom

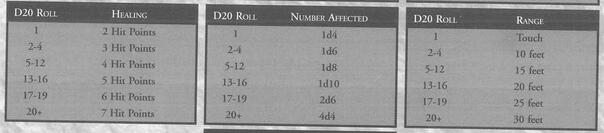

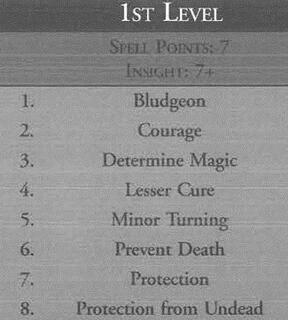

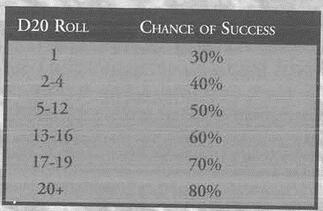

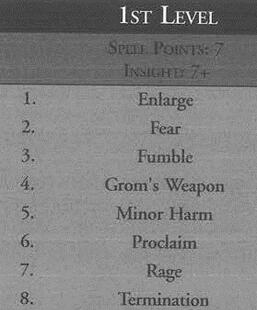

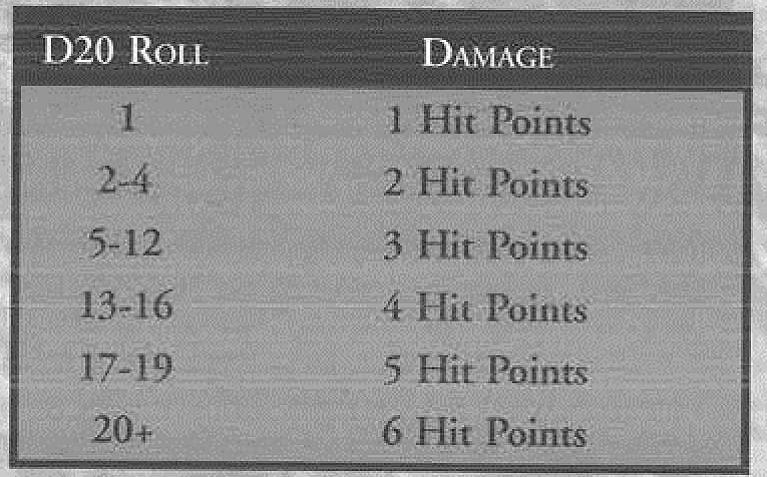

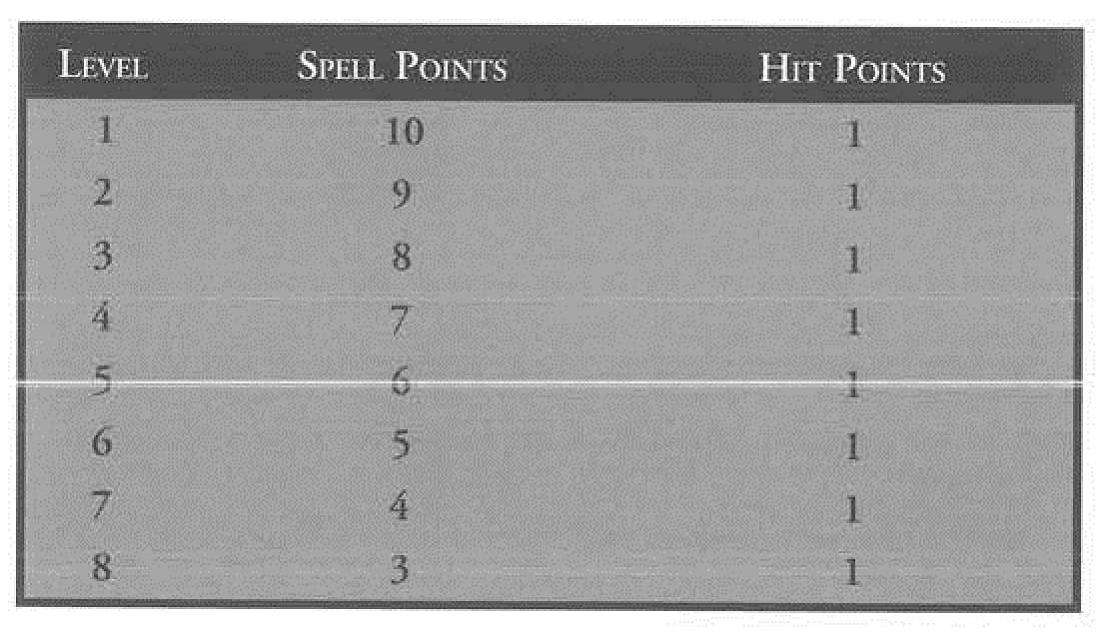

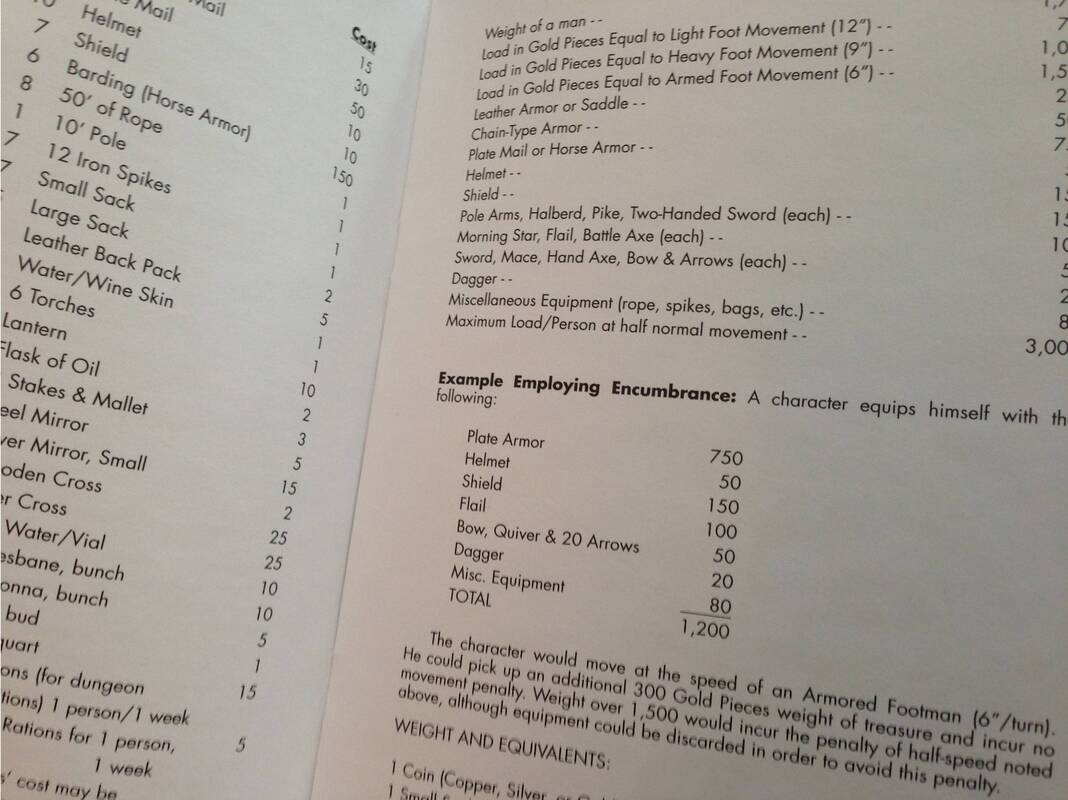

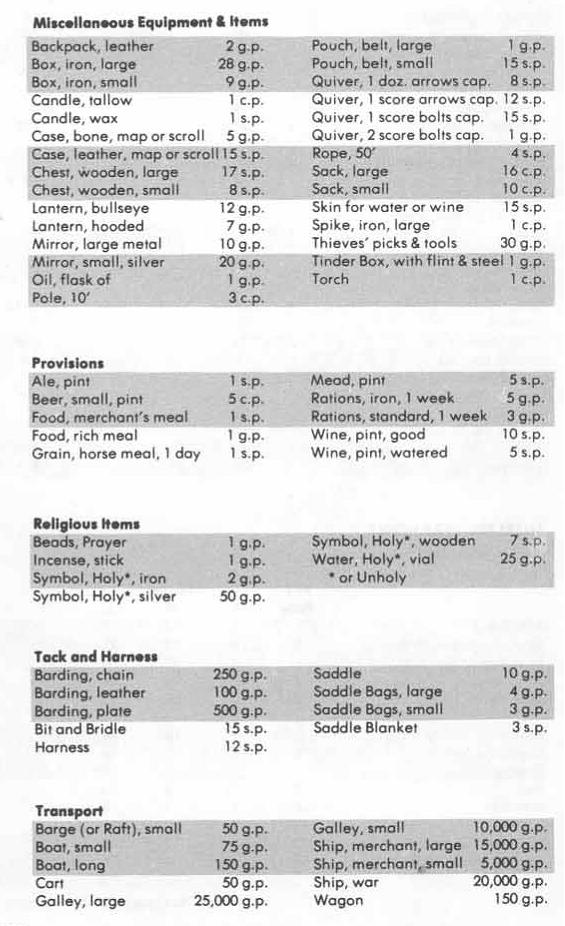

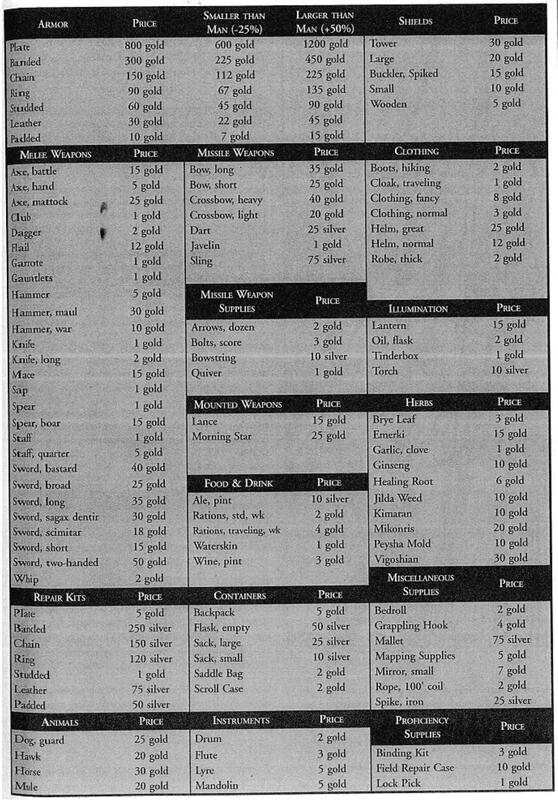

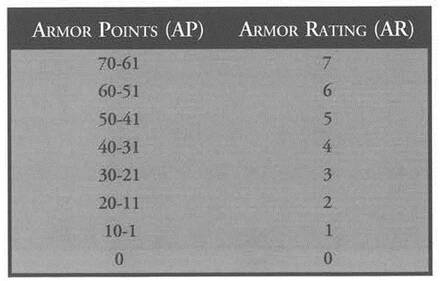

There are a few downsides to Divine Magic compared to Pagan Magic. You cannot spend extra skill slots to be better-than-normal at Divine Magic: Berethenu and Grom give you what they give you and that's that. No taking a chance with higher level spells: at 1st level Magic you get 1st level spells and that's all. You cannot "pump" the spells either, pushing your luck for better outcomes as Pagan Mages do. Finally, advancing in the Magic skill requires acts of servitude to the god (tithing for Berethenu, personal trophies for Grom) and, as usual, there's a clerical code which, if broken, strips you of your godly powers for ever more. Basic Mechanics You get a number of spell slots equal to your Intellect (let's say, 7) and you could fill them with different spells, giving a typical Divine Mage 7 starting spells. First level Divine spells cost 7 Spell Points (SPTS) to cast and a Mage typically has 20-25 SPTS (2d10, doubled), with Kithsara lizardfolk having a half dozen extra SPTS because they are, you know, very mystical. This means you will cast 3, maybe 4 spells before running out of magical juice. Rather than knowing a wide spread of spells, it might be better to start with a smaller selection, say 3, that you are really good at. This is where the 'schematics' come in. These are tables that determine the variable factors for each spell: its range and duration, how much damage it causes or heals, etc. Instead of learning a new spell, you can use up a spell slot to re-roll on the schematics for an old spell and take the better of the two results, or three results if you use up a third slot to re-roll yet again. Going up a level in the Magic skill earns you a bunch of new SPTS (around 15, typically) but also grants you a new set of spell slots. You will use some of these to acquire spiffy new high level spells, but you might use some of them to re-roll your old lower level spells, gaining a +2 bonus for each level higher you are than the spell you're trying to improve. This encourages Mages to develop a honed and curated set of spells, with optimal characteristics for range, duration, damage, etc. It also means that, as the blurb on the back of the book promises: "No two mages are ever alike!" The higher level spells cost more SPTS to cast (14 for 2nd level, 21 for 3rd level and so on) and also have minimum Insight requirements (8+ for 2nd level, 9+ for 3rd, and so on). If you think the 8th level spells look mighty fine, remember that they cost 56 SPTS (OK, you probably have 120 by that point, over 150 if you're Kithsara) and you need an Insight characteristic of 14 (ah... that's a problem). Berethenu Magic: a paladin by any other name The 1st level Berethenu spells give you a flavour of what this god offers. There's Determine Magic (a pointlessly verbose alternative to the D&D stalwart, Detect Magic), Courage (it's Remove Fear), a Lesser Cure (that will be Cure Light Wounds then) and Minor Turning which lets you turn lesser undead, like Skeletons and Zombies, just like a D&D cleric. Protection (which grants a good Armour Rating) and Protection from Undead (which outright repels undead attacks who fail a Saving Throw) have obvious roots in D&D.

Most of these spells have variable Range and Duration and it's not really worth re-rolling these. With its one minute melee rounds (why? why? more about this maddening idea in a future blog), Forge de-emphasises tactical movement, so range is rarely a crucial factor. Even a pretty rubbish 1st level spell will last 11 minutes, which is good enough for most combats.

The higher level spells really just introduce more exciting versions of these effects. At 2nd level Armour grants someone a bunch of magical Armour Points (5 is disappointing, 30 would be amazing!) and that's a pretty significant power. More spectacular healing magic becomes available along with spells that boost Attack Values and Parrying, confer immunity to various horrible conditions and the 5th level Immobilize is our old friend Hold Monster with an even more prosaic name. At 8th level, Resurrection makes its appearance (for those Berethenu Knights with 14 Insight), but that requires the permanent sacrifice of a point of Stamina whether it works or not. This is a functional set of spells that definitely offer an edge in combat, a solution to undead pests and some healing that's faster and more potent than binding kits and Healing Root. It's very dungeon-orientated: everything is for combat or the aftermath of combat. There's nothing like Commune with Deity (understandable, perhaps, since the deity is burning in Mulkra), no spells beyond Determine Magic to answer questions, provide guidance or inveigle clues out of the Referee. Even though Berethenu is god of Justice, there are no spells to detect lies, punish wrongdoers or bind people to their promises. But that's fantasy heartbreakers for you. Their myopic focus on breaking down doors and killing monsters is a virtue if that's all you want to do. But it's a spell list crying out for a bit of elaboration. By the way, notice how, by making turning undead a spell that some Divine Mages will know but others won't, Forge preempts what D&D went and did with clerics? Berethenu Knights have a final power, to convert their Hit Points into extra SPTS. They gain 7 SPTS from doing this - enough to power a 1st level spell. At 1st level of Magic skill, this drains 12HP. Since a typical character has 15HP, you won't be doing this often. But by 5th level, once the cost has dropped to 8HP for 7SPTS, it might be tempting in order to pull off a crucial spell. Grom Magic: putting the laughter into slaughter

Grom's Weapon summons a magical weapon to hand; it's a good weapon too: +1 actual damage, cannot notch, cannot be dropped. This is one of the few spells worth re-rolling to get a good Duration.

Termination is an odd spell. It grants you a high score in the Final Blow skill that you use to decapitate an opponent reduced to 0HP or less, rather than letting them bleed out. Few people bother with this skill, since it's easy to coup-de-grace your enemies once the battle is over - or just leave them to die in agony. But every now and then you need it, such as when enemy Berethenu Knights are healing fallen comrades as fast as you can chop them down. If you learn this spell, you probably want to re-roll it so that it works reliably. Proclaim is that rare beast in this game: a cultural spell. Grom Warriors are supposed to gather yearly in a big rally and boast about their accomplishments. This spell lets you boast alone. Why would you bother with it? Well, for campaign reasons, like setting off on a journey far from home! A rare concession that there might be stuff going on outside the dungeon. High level spells keep the focus on mayhem: blinding people, poisoning them, shattering weapons, demolishing armour, gaining extra attacks, ogre strength, all good stuff. There are more spells that duplicate rarely-bothered-with skills like Gaze Evasion and useful skills like Melee Assassination. There are even some helpful spells, such as empowering and repairing your own armour. While Berethenu Knights are raising the dead, the 8th level spell Vengeance turns the Grom-ite into a berserk killing machine that attacks friend and foe alike. The focus on dungeon skirmishing is less out-of-place here. But since Grom is god of War, it's strange there are no spells for leading armies, staging ambushes, routing infantry or spreading plague. Moreover, there's a lack of sneaky spells. The focus is on the straightforward berserking champion, but surely Grom Warriors can be devious assassins as well. It would be nice to have spells for heroic leaps, surprise attacks, disguising yourself as the enemy and laying traps.

With Grom and Berethenu you get the clear impression of a designer wanting to make clerics 'cool' but impatient with all the 'religious stuff'. What you get are two species of a$$-kickers. In his article More Fantasy Heartbreakers (2003), Ron Edwards ponders why the authors of these indie games were all so indifferent to religion, concerned only with "what must a cleric avoid doing in order to get his healing spells back or when a character gets a minor bonus." D&D 5th edition, with its divine domains and clerical metaphysics, looks back at Forge as across a vast gulf. I'll give some thought to Forge's own take on fantasy mythology in another post. Yet there's no denying that Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors (perhaps, especially Grom Warriors) are fun fellows down a dungeon and, so long as that's where we keep them, their essential incoherence doesn't emerge. If you want to use Forge for a more conventional Fantasy RPG campaign, something with politics and cultural differences and ethical issues to resolve, then can these two clerical killing machines be made relevant? "A good question," as Maz Kanata says, "for another time.".

Last week I posted up a festive one-shot scenario on the Blog. It was my first attempt at a 30-minute dungeon and it was a dismal failure because it took me an hour and a half! But it was a cute tale of a dysfunctional peasant family being assaulted by malevolent winter spirits and the PCs being on hand to save them - a sort of reverse-dungeon where the PCs are defending a site and the monsters are the raiders. I took a bit of time to convert the scenario to Forge Out Of Chaos as part of my project to support this forgotten '90s heartbreaker. The finished scenario is on the Scenarios page. It encouraged me to correct a few mistakes. The scenario features principle NPCs Vadim and Vasilisa who are ordinary peasants but have special ancestors. My first draft was a bit confused about whether heroic Dadushka and witchy Babushka were the parents or grandparents. The final edit clarifies: they were grandparents to the three children and therefore parents to the married couple. This also clarifies a theme that was in my mind when composing the scenario but didn't get the sort of emphasis it needed. Vadim and Vasilisa have both turned their backs on the careers of their adventuresome parents: Vadim is no warrior fighting demons and Vasilisa is no witch safeguarding the home. They are the lesser children of greater parents; they live in a security their parents earned but which they themselves do not appreciate. Vadim doesn't even realise the awl and poker combine to make his father's magical spear Snowmaiden while Vasilisa uses her mother's wand as a distaff for spinning.

The other theme that I muddled on the first draft was the role of Morozko the beggar. I intended him to be an otherworldly figure, with his lunatic-savant babblings and his magical bag of gifts. The tattered robe of red and ermine hints at his true identity: Father Christmas.

The edit enabled me to clarify Morozko's role. Vasilisa turned him away when he came begging and this sin against the ancient code of hospitality is what triggers the family's harrowing. Morozko hides in the lumber shed, plotting revenge, but is discovered by little Nikita, who brings him food and drink. Morozko offers her a gift in return and takes her to the Kurgen - the old Howe where the winter spirits are imprisoned - and opens it. Nikita takes the snowglobe as her gift, but by doing so she unleashes Krampus and the Winterfiends. This might seem a pretty equivocal 'gift': isn't Morozko punishing the child who helped him to spite the mother who rejected him? In a way, yes, but faerie wisdom runs deeper than that. Morozko's gift to Nikita is to return her parents to her: not the unimpressive trapper and his superstitious wife, but the heroic role models that Vadim and Vasilisa can be, if they rise to the challenge of the Krampus. The snowglobe is an apt metaphor here, because Morozko is shaking the little cottage and its occupants, disturbing their peace and security, to bring out a greater beauty when the tumult settles. Of course, for this theme to come across clearly, the PCs' arrival should not be accidental. They meet Vasilisa while heading down a forest trail as night draws on, but how did they get to be there? Perhaps, earlier that day, at a fork in the road, they met an old man in blue and white who directs them down the left hand trail. This figure is Morozko, of course, and he has misdirected them - but only in order for them to pass by the stile where Vasilisa waits for heroes to come to her aid. The revised version includes some advice for the Referee in roleplaying Morozko. He won't be attacked by monsters if there are any other targets. He can navigate the blizzard and part the Holly Hedge to rescue prisoners. He understands everything going on. But he appears to be a gibbering fool. He functions as a 'Referee's Friend' since his crackpot utterances can direct PCs towards vital goals (reading the spellbook, assembling the spear, matching the wand and ring, returning the snowglobe). Ultimately, he could be used as a deus ex machina to bring about a successful resolution, but that requires some inspired roleplaying to get Vasilisa to repent her hard-heartedness and the two adults to demonstrate their heroism to the sceptical winter god. How does it work with FORGE? Forge has some advantages over straightforward D&D in a scenario like this. Most classic fantasy RPGs are games of attrition: your health, spells and weapons get used up and, once they're exhausted, you've failed. Old school D&D suffers from the fact that the PCs have so very little to lose. This can make it hard to tell one of those 'night from hell' storylines where waves of attackers come at the PCs, whittling them down. Most 1st level D&D characters struggle to survive the first whittle! Forge offers characters armour to take the brunt of damage (at least, at first) and Spell Points (SPTS) to use and re-use spells. Then, after an encounter, Field Repair can be used to restore armour and Binding can restore Hit Points, so long as the repair kits hold out. This gives the PCs a bit more longevity in this sort of scenario, meaning the Referee can torment them more enthusiastically. This helps support a group of introductory Forge characters through a night with several bruising combat encounters. Converting the scenario means working with Forge's distinctive mechanics. There are materials in the cottage and the byre that can be used as armour repair kits and binding kits; there are extra healing roots among Vasilisa's stock. Mages can sleep to regain SPTS but, since they need to sleep for at least 2 hours, they will be lucky to get undisturbed rest. However, the spell book upstairs can recharge SPTS if it is opened to the right place. Krampus himself is a ghastly threat. He's modeled on the build for a troll (two claws for 1d8+5 each!) with the added bonus of 1d6 regeneration every round. That's too tough for starting characters, even with a fully-activated Snowmaiden canceling the regeneration. But if you end up fighting Krampus, you've probably failed the scenario. The players need to talk to the NPCs, learn about Vadim and Vasilisa's parents, figure out what Nikita stole from the howe and return it, hopefully with the aid of the Wand and Ring or the Spear to get through the Holly Hedge, but Morozko could be roped in to open the way if the Referee is feeling kind.

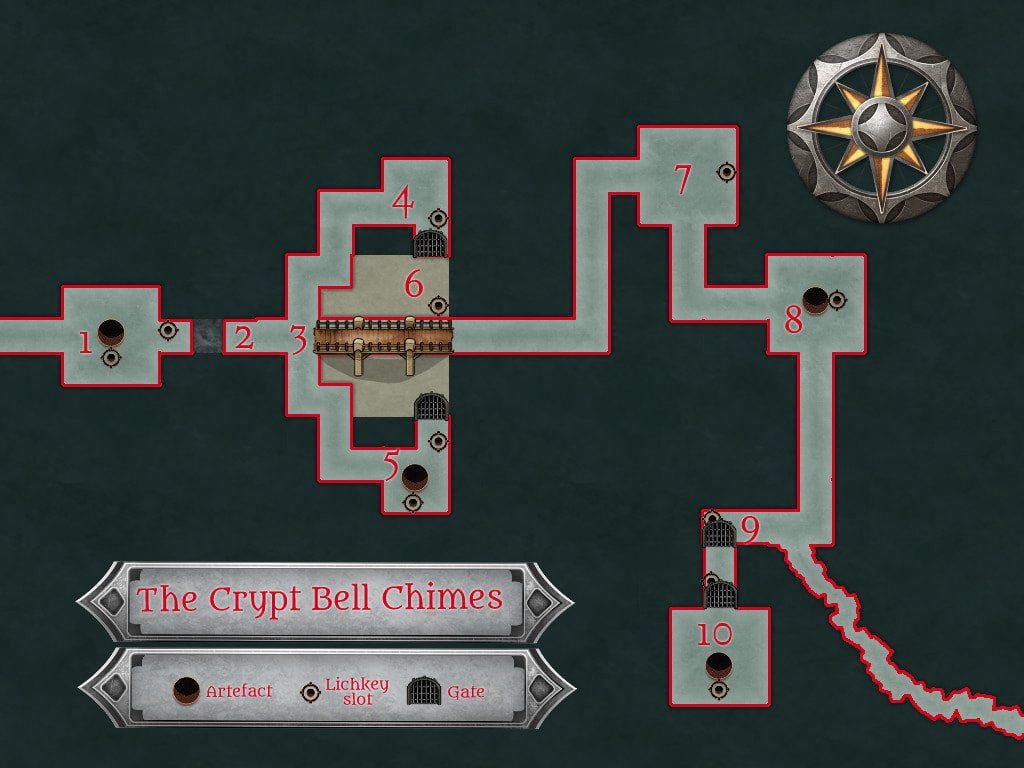

THE CRYPT BELL CHIMES is a 30-minute Dungeon Challenge, as set out by Tristan Tanner in his Bogeyman Blog. I hope it will inspire other people to create some of their own and send them to me - so I can hand out free copies of Forge Out Of Chaos as prizes in the January 2020 competition I used Tristan's optional tables to create an extra discipline for this 10-room dungeon: empty rooms that point to a combat, reveal history and offer something useful to PCs; the special room provides a boon for a sacrifice; the NPC is a rival; the combat encounters are a horde of weaklings, a pair of toughs and a tough boss; the trap is incapacitating. BACKGROUND The masked and hooded Lichkeepers preach that death is annihilation and undeath the only afterlife. They perform the rites of Animate Dead on corpses of the faithful and seal them away in tombs. The tombs are guarded and trapped to prevent the undead escaping. HOOK Ulurok the Unclean was a feared heretic. Now her crypt bells are ringing: the alarm means tomb robbers have entered the crypt. The Lichwardens send the PCs into the crypt to intercept the robbers before they can rouse Ulurok. The PCs are given a Lichkey - a 6" long iron key studded with gems - which can activate or deactivate traps inside the crypt. First, the key opens the gates to the underground tomb and a long tunnel stretches down into darkness, Each room is given a time that the PCs will spend in the room if they examine or interact with it fully. The keyhole symbols indicate points where the Lichkey can be used to interact with a location. 1. THE GUARDIAN GOLEM (5 mins) A 9' tall statue of an armoured reaper dominates the room.; it carries a scythe and am hourglass. It faces into the crypt. A key slot on the dais allows the Lichkey to 'lock' the golem so that it cannot activate. An inscription reads: "Here stand I / Scythe at the ready / Against heresy / And the unquiet dead." The Golem is 6HD, 30HP, AC as plate mail, attacks with scythe for 2d6 damage, unaffected by non-magical attacks. Above the passageway (2) is another inscription: "Ulurok the Unclean, twice cursed, twice buried, let none disturb her nor trust her lies." 2. THE PASSAGE OF TIME (15 mins or less) Hourglass symbols mark the entrance to this passage, which has a Lichkey slot in the wall to the right. An open pit blocks the corridor: it is 10' deep and there is a secret trapdoor in the E wall of the pit, about half way up. The pit is 10' across. Descending and climbing up the other side will take at least 15 minutes, 10 minutes if using Climbing skills or grappling hooks; using spikes and rope to cross along the wall might take 5 minutes but falling in causes 1d6 damage. Beyond the pit is a pit trap which opens onto a chute that deposits victims at the bottom of the pit; they are unharmed but need to climb out again. If a Lichkey is inserted in the slot it prevents the trap from activating so long as a key remains inserted. 3. BALCONY OF REGRETS (1 minute) From the balcony, the Bonevault (6) can be viewed, 20' below, where therre is a key slot to raise the bridge that will reach the exit in the opposite wall. PCs can descend directly (using rope) or take either stairway to the north or south. 4. THE KEY ROOM (5 minutes) Both entrances to 6 are blocked by mesh gates that must be torn or lifted (treat as portcullises). This room has the key slot that lifts both gates. There is a Lichkey inside it. If the LIchkey is removed, both gates open. Every minute there is a 50% chance 1d4 scarabs will enter this room or 5 if PCs are present. 5. THE SOUL-RIPPER (5 minutes) A 10' diameter mystical circle is engraved on the floor with a cage above it suspended from a chain. A Lichkey inserted in the key slot will lower the cage. A living being in the cage is converted into an undead zombie, albeit with some trace of their former identity (low intelligence, recognition of friends). This process takes 5 minutes. A zombified PC will be ignored by the scarabs in 6 but will activate the Golem in 1 if it tries to leave the dungeon. 6. THE BONEVAULT (1 minute + combat) Flesh-eating undead scarabs occupy this room, feeding on the corpses dropped through a chimney over 50' overhead. There is a keyslot that will raise the central section of the floor to create a bridge from 3 to the exit corridor. Scarabs are 1/2HD, 2HP, AC as chain mail, bite for 1 damage, they crawl inside armour so after a successful hit they make subsequent attacks against an unarmoured opponent; 1d3 scarabs attack each character and an additional 1d3 join the attack each round. The scarabs can be turned as Skeletons but new scarabs will keep coming. 7. THE LIBRARY OF THE HERESIARCH (1 minute + variable) Ulurok's heretical teachings are preserved here in a scrolls chained to the wall. The Lichkey can unlock all the chains if it is placed in the slot on the far wall, otherwise each scroll must be unlocked separately (taking 1 minute each attempt). There are 20 scrolls. The PCs can build up an impression of Ulurok's heresy by perusing several scrolls; it takes a PC 5 minutes to peruse one scroll, half that time if Intelligence is high (D&D: 13+):

8. THE SPIRIT CELL (5 minutes) A magic circle is set into the floor, inlaid with silver and gems. The spirit of Ulurok is trapped within. It is visible as a beautiful yet wasted woman, translucent, pleading yet inaudible. If Ulurok's spirit sees a Lichkey in the PCs' possession, she will gesture towards the key slot, begging to be freed. If a Lichkey is inserted in the keyslot in the floor, Ulurok's spirit is freed and will bless the PCs (each heals 1HP) and ask to be restored to her body 9. THE TUNNEL OF OBLIVION (variable) The tomb robbers have broken into this room through the north wall, pushing away the big stone blocks. An earthen tunnel beyond rises to the surface over the course of a mile. The two robbers, Chingiz and Qibilai (see below), are devotees of Ulurok who want to free her from her tomb so that her spirit can speak to her followers again. The final trapped tunnel has two vault doors but the robbers have no Lichkey to open them. It will take Chingiz 10 minutes to find each trap, 10 minutes to deactivate it and 10 minutes to open the lock: it takes the robbers 1 hour to enter Ulurok's tomb (10). The first door has a poison gas trap that fills the room with necrotizing gas: save vs Death or be turned into a Zombie (unintelligent, attacks other living characters). The second door fires darts: each character is hit by 1d6, dealing 1 damage each plus a save vs Poison or tun into a Zombie (as above). Each door has a keyslot and inserting a Lichkey deactivates and unlocks the door; removing the key relocks and re-traps it. There is no Lichkey slot on the inside of the doors. 10. ULUROK'S CRYPT A key slot in the wall will open the iron coffin, which contains a body swathed in chains. If Ulurok's spirit is here, it will renter her corpse restoring it to life. Otherwise, it is a dangerous undead Ghoul. If the tomb robbers get here ahead of the PCs, it will take them 10 minutes to open the coffin, whereupon the Ulurok-Ghoul attacks them. HD 4, HP 18, AC as chain mail, 2 claws for 1d4 each and a bite for 1d6, victims must Save Vs Poison or be paralysed Opening the coffin awakens the Golem (unless it has been deactivated) which makes its way through areas 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9 to confront the awakened Ulurok here (taking 6 rounds). It will attack any characters it finds on the way. Ulurok's spirit can re-enter her body, breaking its undead curse. THE TOMB ROBBERS & ULUROK Chingiz and Qibilai will fight to the death against the minions of the Lichkeepers (i.e. the PCs) but might be persuaded to refrain by Ulurok's spirit, if she is free.

COMMENTARY

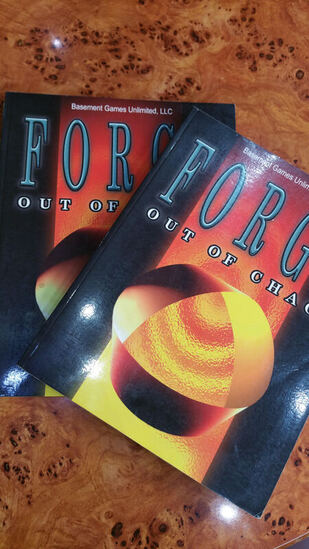

This took 30 minutes to scribble out but I couldn't resist embellishing when I typed out the final draft, so is that cheating? The scenario could play out very simply if the PCs race through the dungeon, ignoring the library and Ulurok's spirit, and intercept the tomb robbers before the open the tomb up. Chingiz and Qibilai can but up a tough fight (one can hide and backstab, the other is armoured and armed with a magic sword) but once they are dead the PCs can exit through the tunnel they created. Things get more interesting if the PCs read the heretical library or interact with Ulurok herself. If they realise that Ulurok is the heroine, not the villain, they might allow her coffin to be opened, but then they have to confront the Guardian Golem, a nasty foe. If they delay too long, the robbers will open the coffin, releasing a dangerous super-Ghoul and also activating the Golem, catching the PCs between two deadly opponents and making the release of Ulurok's spirit the only viable strategy. Whenever I visit my old home town of Edinburgh I drop by Black Lion Games on Buccleuch Street, up by the University. It's a great FLGS (Friendly Local Games Store) with knowledgeable staff who always take the time to chat and it makes me feel proud to see how it's grown from a cellar stall in the '90s to a thriving hobby shop with a consistently diverse and on-trend stock. It's also got four cardboard boxes of discount stock: a mixture of the second hand, the discontinued and the unsellable. Back in the day you'd find old Vampire and Shadowrun stuff here, endless Torg supplements and of course many many dungeon modules. It was dungeon modules I was searching for, to satisfying my OSR urges, but too many people must feel the same way and they're all long gone. Most of the boxes were full of Rifts expansions (there are a lot of these, since it's a game that lets players travel across fractured realities) but in amongst the chaff I found two shiny copies of Forge Out Of Chaos. Near-mint, in fact.

I was inspired by Tristan Tanner's 30-Minute Dungeon Challenge. Tristan challenges himself to write a 10-room dungeon in 30 minutes that contains a Hook & Background, 3 combat encounters, 3 empty (but interesting) rooms, 2 traps, 1 NPC, some treasure and something fun for the players to mess about with. Tristan offers sub-tables if the combat, empty rooms, NPCs, traps and intriguing things need further clarifying. My competition doesn't require anyone to be as strict with themselves as Tristan is: so long as you keep it to 10 rooms, I don't mind how it balances out between combat, traps and NPCs. But Tristan's requirements impose a fascinating discipline that's really tempting to impose on yourself. It's the RPG equivalent of writing a sonnet. The dungeon have to have 10 keyed areas and these have to contain a certain number of fights, rewards, traps and puzzles. The whole thing has to tie together in an interesting way. And you've got half an hour to come up with it. I tried this last week but immediately got carried away: the 30--minute dungeon turned into a 2-hour dungeon and became the Midwinter Nightmare scenario on the previous blog. I'm proud of it as a one-shot scenario but it's not a 30-minute-dungeon. I'm going to have another go. Using Tristan's sub-tables, I roll up empty rooms that point to a combat, reveal history and offer something useful to PCs; the special room provides a boon for a sacrifice; the NPC is a rival; the combat encounters are a horde of weaklings, a pair of toughs and a tough boss; the trap is incapacitating. Here are six scenario seeds inspired by these parameters:

That commits me to 6 stories and I undertake to write up one a week in no more than 30 minutes. I'll post them on the blog and hopefully encourage other people to submit their ideas as competition entries - or just as a bit of fun.

Introduction The PCs are traveling down a winter trail, hoping for lodgings on the shortest day of the year, already drawing to an end, when a desperate woman accosts them at a stile. Her cottage, just a mile inside the woods, is under attack. Will brave adventurers help defend it from a terrible foe? The Referee needs to be familiar with the NPC family and their movements, the location and assembly of the Snowmaiden spear and the Witchhazel Wand, the role of the Zagorvor book and the random events that shape the night’s perils. The Cottage The cottage is home to Vadim and Vasilisa and their three children, teenage son Ivan, younger son Mikul and daughter Nikita. Last night a holy wreath was hammered to their door, a sign that the evil winter spirit Krampus has targeted their home for destruction. They expect Krampus to attack after sunset. PCs can examine and make preparations in one room each before the sun sets. Vadim will gather his family in the Hearth (A) and won’t agree to moving to other rooms. The Woods Outside the cottage a trail leads deeper into the woods, rising to a bald hill overlooking the farm. PCs will barely have time to explore the trail as far as the Holly Hedge (J) before gathering darkness and more snow forces them back to the Cottage. A. Hearth: There is a stone fireplace with an iron pot warming a stew nearby, a solid oak table and five chairs, a workbench with chopping boards and 3 sharp knives. Rabbits and plucked birds hang from the rafters along with onions, radishes and beets. The family gather here. A big iron poker hangs over the fireplace, etched with runes (detected on a Search roll): it is the shaft of Vadim’s father’s spear Snowmaiden, which he dismantled when he settled down and gave up adventuring. On the wall hangs Vadim’s bow and a quiver of 20 arrows. Furniture can be boarded against the windows, forcing invaders to spend a round breaking through, during which time they can be attacked at +2. B. Parlour: The fireplace warms this room too. There is a bench with cushions for the children and a spinning wheel beside a big bucket of yarn. The distaff used for weaving belonged to Vasilisa’s mother who was reputed to be a witch; anyone examining it will notice the arcane symbols on it but Vasilisa does not understand that this is the Witchhazel Wand. Her mother used to weave in here but died last spring. Windows can be boarded up as in A. A door leads to the Byre (F). C. Bedroom: The parents sleep here, with warmth from the fireplace. There is a single big bed with cords knotted tight to support a down-filled mattress. There is a bag of 214 silver pieces under the bed: Vadim’s savings. Vasilisa has a box of jewellery (value 20gp) and some cosmetics and perfume (value 5gp). An embroidered sign on the wall (by Grandmother Babushka) states: “Blade baptized / In Winter’s Breath / Wand and Ring / Bring Winter’s Death.” Windows can be boarded up as in A. A ladder leads to the Nursery (D). D. Nursery: The children sleep and play up here, although Ivan often sleeps in the Byre (F). There’s a box of dolls and carved wooden toys, including a snowglobe taken from the Kurgan (K) by Nikita who secretly plays with it when frightened at night. Mikul’s picture book shows grandfather Dadushka fighting the two Winterfiends, Korschei and Borschei, with his fiery spear and then sealing them away in a house under a hill. E. Babushka’s Room: Since Babushka died, her room has been closed up, but Mikul sometimes sneaks in here because he misses his grandmother. There is a narrow cot and a book of ancient runes : the Zagorvor. It appears to contain nonsensical gibberish in a cramped handwriting. F. The Byre: This lean-too houses Polkan the draft house, Camcha the cow and the ferocious rooster Gorky who attacks anyone except Ivan, pecking for 1 point of damage whenever their back is turned. Ivan can drive him into the coop with the chickens using a broom. Several tools hang from hooks, including a scythe and a sharp awl that is really the blade from Snowmaiden (see 1). Ivan likes to sleep here to get away from his siblings. G. The Well: This is frozen over but there is a mallet to break the ice and a bucket to lower in. If the ice is broken, the steam from the warmer water below can baptise Snowmaiden. H. Babushka’s Grave: Marked by a single stone, as she wished. Babushka’s body, which takes an hour to disinter, wears the Rowan Ring. I. The Timberstore: A ragged vagrant sleeps here, unknown to Vadim and his wife. Nikita knows he is here and sometimes brings him out buttered bread to eat or milk to drink; in return, he takes her up to the Kurgan (K) to look for trinkets and they found the snowglobe in the doorway. He is Morozko, a peddler, turned away by Vasilisa. J. Holly Hedge: a trail winds up the hill to the Kurgan, passing through a dense wall of holly. At night, the holly hedge blocks the path unless magic is used to part it. K. The Kurgan: An old burial mound whose stone door has fallen away from the hinges. At night, an eerie light shines out and the Krampus is here along with sleeping prisoners. If the snowglobe is returned here, the curse is broken. Encounters each hour Roll 1d10 for an event every hour. There are 10 events in total and when all have occurred, the Krampus will arrive in person. Each event only occurs once except for 1 and 2, which can occur twice.

Reactions after each Encounter After each event, the NPCs will react in various ways: roll 1d8. If a reaction affects a NPC who has been killed or captured, re-roll. PCs never see a NPC leave unless they are personally guarding them, in which case they will notice their departure immediately and, if they pursue them, are considered to be at their location when the next Encounter begins.

Key Items THE SNOWMAIDEN SPEAR Snegurochka or ‘Snowmaiden’ is the magic spear that Vadim’s father Dadushka used to defeat the Winterfiends decades ago. It has been split into its iron shaft (the poker in A) and blade (the awl in F) which can be reassembled to make a +1 magic spear. If Snowmaiden is ‘baptised’ in winter breath (steam from the well or the blood of dead white wolves), the spear’s full powers activate: magical +2, immunity to cold/blizzards, able to cut through the holly hedge surrounding the Kurgan (K) and Krampus cannot regenerate its damage. THE WITCHHAZEL WAND The Wand was the possession of Vasilisa’s mother Babushka and protected the Cottage until her death. Vasilisa has been using it as a distaff. It can be used to create a circle of protection in a 2’ radius of the bearer that cannot be entered by Elfs, Winterfields or the Krampus; it guides unerringly through the blizzard. If used with the Rowan Ring, it can cancel the blizzard, open the holly hedge (J) and allows the bearer to turn the Krampus (D&D: as a 4th level Cleric; Forge: spend 12SPTS, 30% success). THE BOOK OF ZAGOVOR Babushka’s spellbook is incomprehensible gibberish to other readers, but it will fall open at an important page for Mikul or be found at that page after the event of ‘footsteps in the bedroom’. This page explains in detail how to baptise the Snowmaiden, wield the Witchazel Wand and Rowan Ring and how to pass through the holly hedge (J) into the Kurgen (K). Key NPCs

VASILISA: the Mother

D&D: 3 Hit Points, AC as unarmoured, attack with kitchen knives or scissors for 1d3, Lawful Good; Forge: 12HP, DV1 1, DV2 0, attack for 1d3, ST 11+. SPD 3 Vasilisa was raised by her witch mother to be intensely superstitious and goes in dread of the tall, bald hill in the forest known as the Kurgan. She misses her mother greatly and has preserved her room untouched, but she has one of her grandmother’s magical skill. She does not realise the distaff in B is a wand but recalls Babushka’s Rowan Ring which was buried with her outside. However, her love for her children is such that, if any are kidnapped, she will acquire the ability to use the Rowan Wand. VADIM: the Father D&D: 5 Hit Points, AC as leather, with cudgel for 1d6, Lawful Neutral; Forge: 15HP, DV1 2, DV2 2, 20AP, attack for 1d6, ST 10+. SPD 3 Vadim is the son of an adventurer, Dadushka, who gave up adventuring and dismantled his magical spear Snowmaiden. Vadim does not believe the old tales of his father wielding a magic spear but can identify the iron shaft in A as being from Snowmaiden. If Vadim’s children or wife are lost, his steely heritage will assert itself; he acquires +1 to hit and damage and will remember that the awl in F is the blade to Snowmaiden. IVAN: the elder son D&D: 3 Hit Points, AC as unarmoured, attack with broom for 1d3, Chaotic Good; Forge: 10HP, DV1 1, DV2 0, attack for 1d3, ST 12+. SPD 3 Ivan is a sullen teenager who is impatient with his siblings and angry with his parents. He has much of his grandfather Dadushka in him and likes to handle Snowmaiden’s blade (F): he senses it is magical but does not know it fits the poker in A. He knows that Nikita often sneaks away to the Timberstore (I) where she has an imaginary friend. He knows that Mikul is always sneaking into Babushka’s room (E). However, getting him to open up is not easy. He will idolise a strong stern warrior or an attractive, courageous woman among the PCs. MIKUL: the younger son D&D: 2 Hit Points, AC as unarmoured, no attacks, Neutral Good; Forge: 8HP, DV1 1, DV2 0, attack for 1d2, ST 14+. SPD 2 Mikul is 10 years old and was very close to his grandmother, who taught him much witch wisdom and gifted him the storybook in the Nursery (D). He has enough raw magical talent to use the Witchhazel Wand, knows that the distaff was Babushka’s wand and knows too that Babushka was buried with her magical ring. However, he will never speak of these things in front of his mother, because she scolds him out of superstitious dread. He knows that an odd man is living in the Timberstore (I) that Nikita calls ‘Mr Frost’. NIKITA: the youngest daughter D&D: 1 Hit Point, AC as unarmoured, half normal movement, no attacks, Neutral Good; Forge: 6HP, DV1 1, DV2 0, attack for 1, ST 15+. SPD 1 Nikita is 5 years old, with her grandmother’s fey and independent spirit and her grandfather’s boldness. She takes cakes and milk out to Morozko (‘Mr Frost’) but doesn’t speak of him around her parents. Morozko offered her a gift, which she refused, so he took her instead up to the Kurgan one morning and she fund the snowglobe there and brought it home. She keeps it secret and plays with it whenever she is distressed. MOROZKO (Mr Frost): peddler D&D: 4 hit points, AC as leather, attack with sling for 1d3, True Neutral; Forge: 16HP, DV1 2, DV2 1, 10AP, Sling for 1d3, ST 6+. SPD 4 A filthy tramp with verminous beard and hair, yellow teeth and rheumy eyes, Morozko wears a tattered red shirt and trews with an ermine trim that was once fine. He prattles nonsensically about the weather, his sisters the stars, the old warrior in the Byre, the cannibal twins and the wisdom of children; he has the ability to scold characters about their deep anxieties (Vadim that he is unworthy of his grandfather, Vasilisa that she does not protect her children from evil, Ivan that he will never amount to anything, the PCs on whatever weaknesses the Referee decides are appropriate). Morozko carries a sack with magical properties: although it appears empty, he can draw from it a gift for anyone who has shown him kindness or respect. Use this brief table or roll on an expanded table such as https://basalt-dnd.tumblr.com/post/153238499847/random-trinket-table

I was looking for a short mini-dungeon to introduce some players to Forge Out Of Chaos - something I could convert that didn't lean to heavily on tropes specific to D&D - and along came Tamás Kisbali, posting up a link to his Eldritch Fields blog where there's a 30-minute dungeon called 'The Golem Master's Workshop.' The 30-minute Dungeon Challenge was devised by Tristan Turner on his Bogeyman's Cave blog and it goes like this: "I will sit down for 30 minutes and write 10 rooms/encounters for a short mini dungeon ... here are my general guidelines for what I make when writing one of these dungeons: a Hook, General Background, 3 Combat Encounters, 3 "Empty" Rooms, 2 Traps, 1 NPC, 1 Weird Thing To Experiment With, some Treasure, a Magic Item." Well, that's just fantastic, isn't it? It demands to be done! But first I looked at Tamás Kisbali's contribution and decided his Golem Master mini-dungeon was perfect for my purposes. You can download his original version here or my Forge conversion over on the Scenarios page. SPOILERS AHEAD if you're hoping to play through it because I'm going to offer up a session report and a bit of analysis about Tamás' excellent construction work. The Golem Master, creator of pricey artificial servants, hasn’t been seen around for some time. His house stands dark and silent. Dare you enter? Tamás Kisbali's crisp introduction paints an intriguing portrait. Here is a world where golems are made to order by master enchanters. Not the lumbering monsters of D&D bestiaries in their clay, stone, iron and flesh iterations. No, these "pricey artificial servants" are supernatural cyborgs, androids ... simulacrum, as medieval philosophers called them. Strip away the fantasy veneer and this is a SF premise: a robot maker, deep in his mansion, has been making compliant replicants but now something has happened to him. Sounds like a job for a Blade Runner. But another theme is at work. Read through the scenario and the names jump out: not just golem but Jakov and Boax. The Hebrew (or erstaz-Hebrew) language takes us to the Prague ghetto, the story of Rabbi Loew and the legends of European Jewry. The Golem Master seems to be, not just an enchanter, but a Jewish rabbi, or something rather like one. That means, what unfolds here is a spiritual fable about the gift of life and the curse of hubris. Of course, Blade Runner (1982) merges spiritual fables and science fiction, placing origami unicorns alongside those C-beams glittering in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. Sheesh. A one sentence introduction and I'm excited to get inside this one. An Open Dungeon The Workshop has the hallmark of the Open Dungeon design: an entrance chamber with no threats but three doors leading out. All directions are possible (but one door is locked). Rather like the forbidding steps down into Zenopus' Dungeon reviewed earlier. the Workshop's entrance hall provokes the imagination. You leave behind a prosaic street scene of business chatter and market vendors. You enter a place of silence and mystery. The desk ledger bears accounts of golem sales - that's the outside world of banal financial transactions - and the purchase of "of raw clay, for new personal project" - something more numinous. From the impersonal to the personal, the transparent to the mysterious: penetrating the Workshop is a journey away from the orderly and rational into madness and obsession, but also away from the world of consumption to that of creativity. It's a journey into the artistic mind that will conclude with an opportunity for the PCs to become creators and bestowers of life, for better or worse... The left hand corridor with its mud stains leads to the storeroom where the crippled golem Jakov lies dismembered, but still loquacious. His insane brother Boax can be found in the studio through the other door, pretending to be a statue and protected by his loyal gargoyles. Sequencing comes into play, because if the PCs visit Jakov first, they might recognise Boax for what he is; if they don't have that conversation, they'll be taken in by the mad golem's ruse. Another room holds a scroll than can be used to incapacitate Boax, but might find more dramatic use at the end of the scenario if the Quantum Golem is animated and runs mad. The locked room hides a great horror moment as clay hands scrabble across the floor and leap for the throats of the intruders. If the players identify and dispatch Boax before venturing downstairs, the basement offers rewards and explanations. The Golem Master is down here, maimed and quite mad, determined to complete his gigantic Quantum Golem. His patchwork abominations, built to guard him down here, are a concession to necessity, but also embody his fractured mind, magical creations with all beauty ruined. The Quantum Golem, if animated, makes a formidable ally but that scroll might be needed if it runs amok. The players are taking their first steps down the path that the Golem Master has trod before, bestowing life recklessly and bearing the bitter consequences only later. It's a Rat Trap - and you've been caught! If the players fail to identify Boax, he will trap them below stairs. The Open Dungeon turns into a Rat Trap and events down below become much more fraught. Possibly not understanding what has happened upstairs to block their exit, the PCs explore the basement and find themselves in a tense game of cat and mouse, with the cackling Golem Master in the shadows and his gruesome Abominations leaping out to attack. Someone will fall through the floor into the clay pits, which represent the raw id of the Master's imagination, now stripped bare and exhausted. A confident DM can make the Master eerie and upsetting, but the Abominations don't pose too much of a threat. The real dilemma is whether the PCs should animate the Quantum Golem in order to break out. If it doesn't go mad, they can use it to smash through the trap door and clobber Boax; if it goes crazy, that magic scroll might incapacitate the creature once it's served its purpose. There's a substantial treasure trove for low level characters, but the biggest treasure is the Quantum Golem, assuming it stays sane. Adapting for Forge The Forge conversion is easy because the monsters are original creations. Unarmoured monsters in Forge are quite vulnerable to being ganged-up on, even if they have a high Armour Rating (AR). To counter this, I've given Boax the partial resistance to blunt weapons you find with zombies and also made the Quantum Golem's stone exterior capable of notching weapons. I decided on a name for the Golem Master: Belazal nods to the creator of the original golem in Jewish folklore, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel. A significant change I made was the spell scroll. To aim for authenticity, this is now an instruction manual for deactivating golems, removing the empowering magical letters (spelling emeth or 'truth') from their foreheads. It can be used repeatedly, so long as the PCs have Spell Points left. I moved it from the unlocked bedroom to the locked study: I figure if the players break into a locked room and fight grisly disembodied hands, they should be rewarded with something potent, but the 'key' to the scenario shouldn't be left lying about in the open. The players will need it, because I've intensified the drama downstairs. Belazal will do anything to see his Quantum Golem completed, but, if this is done, will order it to attack the PCs (such gratitude!). The Quantum Golem has to keep making saving throws to resist going crazy every time it is given an order, every round it spends in combat and should Belazal ever be killed. This means the PCs are almost certain to end up fighting it if they reanimate it, but hopefully only have to endure a few rounds of battering from its terracotta fists before it goes on a rampage across the city. I added in the (incomplete) female golem Lizbjet to explain Boax's rage against his creator. Boax thought that Lizbjet was to be for him, but of course the Golem Master made her for himself (in what capacity, you may let your prurient imaginations loose). Boax's rage is Oedipal: he assaults and castrates his 'father' to assert his sexual autonomy but is trapped by the consequences of his crime, since only the Master can make Lizbjet live, yet if he does, she will love the Master, not Boax. There's perhaps little the PCs can do to alter these outcomes, but understanding the interpersonal conflicts at play makes the dungeon more satisfying and there might be leverage here if the PCs can promise Boax that they can animate Lizbjet - or make him believe they can persuade Belazal to do so. So, how did it go? Two characters (Rammstein, a Dunnar necromancer and a Renny Squirmfoot, a Jher-em warrior) entered the workshop. They enjoyed the puzzle aspects of working out what had happened. They made their way to Jakov first of all, then opened the study to fight the many hands. However, they didn't explore the studio carefully enough to expose Boax and went straight downstairs (though they did drop a gargoyle down there and it went crashing into the clay pit). Once they were in the basement, Boax trapped them down there. The Abominations didn't cause too much trouble, but Belazal was a fun lunatic to roleplay. The players reanimated the Quantum Golem and were appalled at Balazal's perfidy when he ordered it to slay the intruders. Cat-and-mouse ensued, with the golem crashing after the PCs and delivering horrible wounds but the PCs keeping just ahead of it. When Rammstein killed Belazal, the Quantum Golem went mad, bursting out of the trapdoor, slaying Boax and crashing out into the street. Poor Renny died from the poisoned door trap but Rammstein successfully used the scroll to deactivated the Quantum Golem, but only after it had caused enough mayhem to make him look like the saviour of the city. The scenario lasted about 90 minutes: a perfect evening of light OSR roleplaying. It's the sort of premise that deserves a bit more time and a bit deeper consideration. That's to say, it lends itself to a lot of non-fantasy RPG games. It would be great for Call of Cthulhu, obviously, or Kult, with its shifting realities and illuminating madness. Vampire: The Dark Ages would be a fun vehicle for it too. A bigger map and a more sprawling mansion would allow Boax and his gargoyle minions to stalk the PCs. If Lizbjet were to be alive and functional - and perhaps in love with the mutilated Jakov rather than either her creator or deranged suitor - then the roleplaying aspect would be even more dynamic.

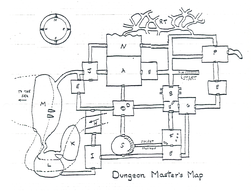

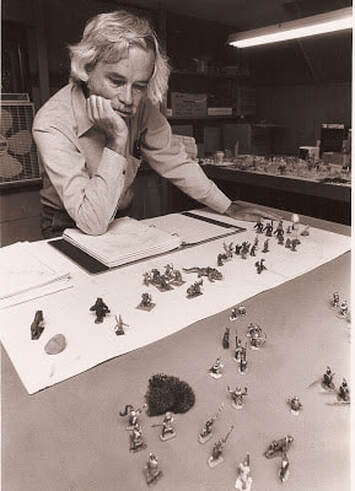

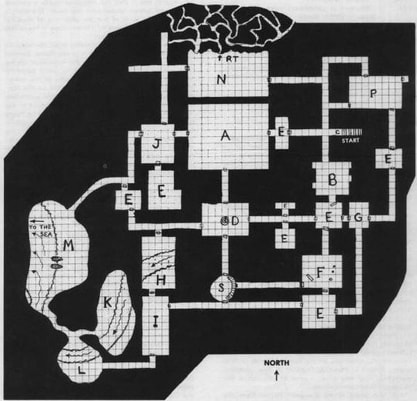

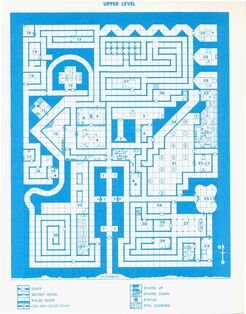

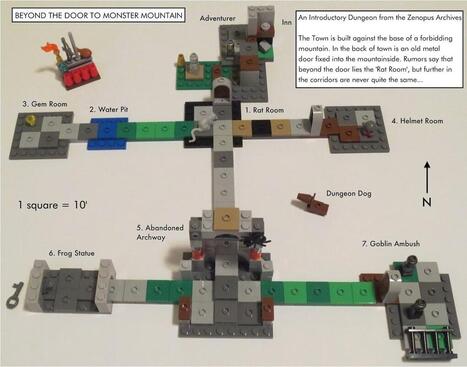

Over on the Scenarios page, I've posted up an adaptation of 'Tower of Zenopus' which has a special place in FRPG history. Back in 1977, TSR published the 'Blue Book' Basic Dungeons & Dragons set, written by Eric Holmes. Holmes was an author, psychologist and gamer who approached TSR as an outside writer with an offer to bring together their scattered Dungeons & Dragons rules in one introductory set. Gary Gygax's company agreed (Gygax himself was working on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules which would see print in stages over the next few years) and Holmes quickly created the version of the game that roleplayers of a certain vintage remember as their first introduction to the game - indeed, it was my first introduction. Gygax was a weird polymath with a fascination for medieval details but Holmes was the more orderly mind and, as an author, a better stylist to boot. In place of Gygax's long-winded and rather scholarly disquisitions, Holmes was the master of the poignant detail that lodges in the imagination. His 'Sample Dungeon' at the end of the blue rule book is a master class in early dungeon design that clear illuminates the way the hobby was to go forward - or perhaps, the way it should have gone forward, for Holmes' imaginative ideas were not all followed through by subsequent D&D output. Anyway: SPOILERS AHEAD - so if you're planning on playing through this iconic early dungeon, stop reading now before I give everything away. One hundred years ago, the sorcerer Zenopus built a tower on the low hills overlooking Portown.... So begins Eric Holmes' introduction to his dungeon adventure, setting the scene not just for a one-off scenario but, for many hobbyists, the guiding conception of what a FRPG adventure should in fact be: the template, the paradigm. Holes' introduction glances back into history, not just to a century ago with Zenopus, his tower and his ill-advised underground research, but further back, to "the ruins of a much older city of doubtful history," a phrase redolent of H.P. Lovecraft's eerie understatements. The glance backwards is also a glance outwards, to the graveyard nearby and the sea-cliffs facing "the pirate-infested waters of the Northern Sea." Readers are offered hints of three adventurous genres: swashbuckling pirates, necromantic graveyards and eldritch mysteries out of pre-human antiquity. If one of those doesn't float your boat, then what are you even doing here? Zenopus departs in grand style, with his tower engulfed in green flame by a nameless horror unleashed down below. Holmes adds further macabre touches: ghostly lights and ghastly screams and "goblin figures ... dancing on the tower roof in the moonlight." The last detail possesses a weird faerie poetry, like something out of folklore or nightmare, quite at odds with the prosaic direction D&D took under Gygax and TSR. We're treated to an account of the fretful town elders wheeling out a big catapult to batter the tower to rubble. There's a nice juxtaposition here of the secure life above ground, with its civil authorities and their catapults that put a stop to unsettling hauntings, with the below-ground world of the dungeon, the place of unanswered questions, of fatal ambition, a world of transformation: Holmes concludes with the image of "a flight of broad stone steps leading down into darkness." Do you stay up above in safety, in a "a small but busy city" with its fancifully named inn ... or descend and take your chances in the Otherworld of mystery and romance? You can tell Holmes was a psychologist. He might as well have called the town Ego and the dungeon Id. The Open Dungeon Design Holmes' dungeon - let's call it the Zenopus Dungeon, although he never names it - establishes a template for the open dungeon design, in contrast to the Monster Mountain dungeon I reviewed last week. 'Monster Mountain' was a cross-stitch dungeon laced with breadcrumbs to send players this way and that on a pre-plotted narrative. You might feel as though you are exploring and discovering, but really you are enacting scenes the designer has already envisaged: you, using the ladder to cross the moat; you, feeding your new gems to the frog idol and receiving a key; you, unlocking the door to find a treasure revealed. In the Zenopus Dungeon, there's no such plotting. It's a true sandbox. You can go anywhere and encounter the rooms in any order. Yes, some encounters are likely to precede others. Room A, with its goblinoid guards, lies nearest and directly ahead. Some encounters make more sense if discovered in a certain order: meeting the Magician and having him escape before discovering the basement to his tower. But even here, events are intriguing if they are sequenced differently. The tower is a more baffling but exhilarating discovery if you don't know who owns it. Other encounters tell different stories depending on the order they present themselves: encountering Lemunda the Lovely and her pirate captors before meeting the the hapless former-pirate who has been charmed by the magician, compared to meeting them afterwards. In an open dungeon like this, a number of narrative elements are in flux. The arrival of the PCs is a catalyst for change and process. At the very least, some evil inhabitants will die and prisoners be released. More interesting things can occur too: alliances against a common enemy, revenge against a hated foe. Holmes assumes that players will attack dungeon denizens on sight, but offers ideas in case they don't: the goblins will surrender when half their force is dead, the charmed warrior is a former-pirate whose curiosity got the better of him, the evil magician is trying to take over the dungeon, the ape who hates his cage, what becomes of the victims petrified by the magician's wand? ... Stories can emerge out of this but don't have to, which means that each group that enters the Zenopus Dungeon will create different outcomes that reflect their choices and values, as opposed to the Monster Mountain Dungeon, in which each group must experience a story, but always the same story. Space for the Imagination As a writer, Holmes knows that he will never surpass the pregnant image of the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness": everything that comes after will fall short of what we imagine is down there. So he wisely delays disappointing us. His dungeon is spacious and most of it is corridor. Once downstairs, there's a crossroads, with passages heading off into intriguing darkness, through shadowy archways or up to firmly sealed doors. Time for debate and dissension. Head north and the tunnels go on and on, then branch and twist around. Head south and there's a chamber of dark alcoves and a tempting opened door. Those that head straight on find empty rooms, more doors, more tunnels. These corridors are where the party form their marching order, arguing about who goes at the back, disagree about who's in charge. These dynamics are important, not least because, the whole time, anxiety is growing. When the party finally burst into a room to find armoured goblins, rattling skeletons or slavering ghouls, their will be a blessed release of tension and combat will come as a delight. So many dungeons forget this. Take a nostalgic look at Gary Gygax's 1979's D&D Module B2 (The Keep on the Borderlands) and look at the strangely orderly Caves of Chaos. They're packed so tight, with an encounter round every corner. Gary Gygax gives adventurers no space to roam nor time to let the dread grow. See how poky it is compared to Zenopus (underneath, left)? To be fair to Gygax, he also designed 1979's D&D Module B1 (In Search of the Unknown, above right), which is more Holmsean in its layout, with corridors to get lost in. But the direction of travel under Gygax is clear: away from the baroque and towards the modern, even the minimalist. Dungeons cease being metaphors for the labyrinthine unconscious mind; they become mere underground pieces of real estate. Thematic Compass The Zenopus map may be sprawling, but the geography is artfully themed. Up north is Horror Land: the Rat Tunnels, the ancient city crypts, skeletons leaping out of sarcophagi and alcoves, ghouls dining out of coffins and spiders in the ceiling, everything is jump scares and cobwebs. Down South is Wizard Wonderland: the magician and his tower and his vengeful ape, a talking mask and a rotating statue, a realm of puzzles and whimsy. Over to the west is Pirate Adventureland: an underground river to cross, me hearties, aye and a sunless sea, a giant octopus and smugglers belike with a beauteous prisoner, d'ye see? Players won't be aware of moving from one theme park to another, but the imaginative consistency has a cumulative effect. In Wizard Wonderland, players might roll their eyes at the rotating statue puzzle but by the time they reach the magic sundial and the talking mask, they'll suspend their disbelief entirely. In Horror Land, the crumbling decay and dusty despair grows in intensity from room to room, until the sudden eruption of a giant rat from the wall prompts the same alarm as a phalanx of skeletons. But once we enter Pirate Adventureland, real world dramas take over. How to cross a fast flowing river? Never mind undeath, you might actually drown? The appearance of the delightfully un-magical pirates in the westernmost cavern is well-prepared. The players are ready now to suppress a more conventional foe for a more worldly reward: the rescue of a powerful lord's daughter. Again, Gygax's B2 module comes off the worse by comparison. In the Caves of Chaos, regions are themed purely by the monsters living in them, but the kobold caves are exactly the same sort of place as the hobgoblin barracks. The monsters might acquire more Hit Points but there's no shift in genre. You could play through Zenopus' Dungeon in one (long) sitting and experience three broadly distinct chapters or acts, but I'd defy anyone to persevere with the Caves of Chaos for that long. The endless monster-bashing becomes wearying. The distinction is due to Holmes' psychoanalytical interest. His dungeon is the landscape of the mind, of dreams and nightmares and, over in the western reaches, of the Super-Ego, bringing justice to piratical lawbreakers and rescuing the innocent. Gygax's Caves of Chaos, despite the name, owe nothing to Freud or Nietzche. They represent our world, the dense urban sprawl, with the PCs as policemen or vigilantes or looters, acting out troubled 20th century fantasies of order and arbitrary power. Ways of Escape There are Rat Trap Dungeons, where the PCs at some point hear a portcullis crash down or a rockslide rumble past or a giant granite block slide into place and realise they cannot exit by the route they entered. Gary Gygax's Module B1 turns into a rat trap when an infamous pit trap drops the party down to the lower dungeon level. Everything changes from that point. Now, Hit Points and resources have to be curated carefully. The PCs are advancing into an uncertain future and don't have the luxury of wasting energy or ammo on unnecessary encounters. It's gripping. I'll look at two Rat Trap style dungeons in the next few weeks: Tamás Kisbali's 'The Golem-Master's Workshop' and Albie Fiore's 'The Lichway'. But Zenopus is not a Rat Trap Dungeon. Quite the opposite, there are lots of exits from the dungeon: from the coffin rooms through a dirt tunnel to the cemetery, through the sea-cave out into the ocean and up through the Magician's Tower to emerge blinking into a busy Portown street. One exit from each 'theme park' in fact, embodying the themes of horror, surprise and exploration. Holmes has a philosophy on his side. Old school dungeons like this are meant to be riddles, not sagas; sprints, not marathons. You dive in, hit it hard and get out, then heal up, re-equip and delve again. If you over-extend and get into a fight while too low on resources, well more fool you and an ugly death awaits. Since Holmes is very conscious of how he intends his PCs to function, he places these exits to facilitate the style of play he wants to see. No need to hike back to those forbidding stairs, risking Wandering Monsters; no need to keep entering by them either. That ominous invitation of the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness" won't stale with repetition because the players won't be repeating it; on the second session, they'll be re-entering the dungeon through the Magician's Tower or the sea-caves or even the cemetery. There's a lot to be said for understanding how your want you players to function and building your dungeon to reward that. Holmes adds multiple access points so starting PCs can make many short jaunts. Holmes the psychologist is also reorientating the players' reality. As long as the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness" were the dungeon's entrance, the distinction between this world and the Other, between conscious and unconscious mind, was clearly marked. But now the cemetery - death itself, or the fear of it - also leads into the subconscious playground and so do the "pirate-infested waters of the Northern Sea," showing that our political and economic anxieties and our interior struggles are not so distant. Finally, the prosaic street scenes of Portown lead directly into the dungeon if you know the right door to open. The unconscious waits round every corner, right under your everyday feet, and the experienced adventurer is the one who knows that best. That's what leveling-up means in a Holmsean dungeon. If you want to know more about the room-by-room experience of this dungeon, there's a great breakdown from RPG Retro Review. How does it play with FORGE OUT OF CHAOS? Forge conversion requires little analysis, since almost all the monsters (whether men, rats, skeletons, spiders, snakes or ghouls) are monsters in Forge too, with similar characteristics. The Giant Crab is easily substituted for one of the innumerable silly giant insects in the Forge bestiary, this time the one with the resoundingly banal name of 'Dweller'. In general, Forge monsters are slightly tougher than their D&D equivalents, but this is OK since Forge PCs are more resilient too, since their armour soaks up damage and they have access to casual healing from herbs and binding kits. This resilience can work against Holmes' underlying philosophy. Unlike a squad of Basic D&D noobs, even starting Forge adventurers can stand up to several encounters before armour gets shredded and hit points are low. They should be able to cleanse the whole dungeon in two journeys, especially if their first one is lucrative (i.e. they went north into Horror Land). This works against Holmes' in-and-out-again intentions, meaning that the multiple exists and entrances won't feature so significantly. To balance this out, I made a couple of alterations to the dungeon. One is to add a Wandering Monster table that sets the population in motion and re-stock rooms, which punishes PCs who dawdle and makes doubling back rather more problematic. One of the Wandering Monsters is a truly nasty entity: the Dungwala is one of the creepier (but still stupidly-named) monsters from the Forge bestiary. A sort of evil predatory mist, it envelops a victim, paralyses them and suffocates them, eventually vanishing with their corpse. Worse, this thing is only harmed by magical weapons. Forge characters have a few spells that surrogate for magical weapons, but more to the point Zenopus' Dungeon is full of magical weapon treasures, so successful adventurers should acquire the resources to deal with this horror. But perhaps the first times it shows up, it will take a life or make a wise party flee. It's presence seems to me to vindicate the lurking dread implied in Holmes' introductory text. I've named the magician and his bodyguard using the Holmesean name generator at Zenopus Archives. Lemunda the Lovely needs more consideration, since helpless damsels are a tired trope in fantasy adventure. To give Holmes his credit, he seems to envisage Lemunda joining a party of adventurers as a fighter rather than sobbing and begging to be taken home. Adding a love interest between her and Bru Preslap (the charmed former-pirate bodyguard) makes things more interesting. In Forge combat, you rarely kill opponents outright, so it's an option to defeat the magician's guard without murdering him. Whether the players choose to be so forbearing is another matter. Mezron the Mysterious, as I've named the evil magician, is a different proposition. In Holmes' dungeon, he was a 4th level Magic-User who could threaten an entire party with spells like Web, Charm Person and Magic Missile. Forge Enchanters aren't nearly as threatening, since their spells take 5 minutes to cast per level. However, since he's supposed to run away and fetch his petrifying wand, I figure that doesn't matter. I made the wand dependent upon Spell Point expenditure to discourage victorious PCs from over-using it in future encounters. I never liked the idea of charges in wands. Finally there's the 'Goblin Conversion' probem you always get in Forge. This time I went with Higmoni. I dislike casting them as the Orcish bad guys because they're a PC race that (I feel) deserves better than that. However, I'm over-using Cricky Hitchcock's Svarts and, in this case, Holmes does an interesting thing: he mandates that the goblinoids match or exceed the number of PCs, rather than a fixed number or random spread, and that once half are dead the rest will surrender. This means that the Higmoni offer a bruising encounter (combat against armoured PC-peer opponents in Forge is always tough), but one that gets cut short before too much harm is done. The PCs the have the option of dealing with the Higmoni 'as people'. OK, as duplicitous, backstabbing people, but that's people for you the world over.