|

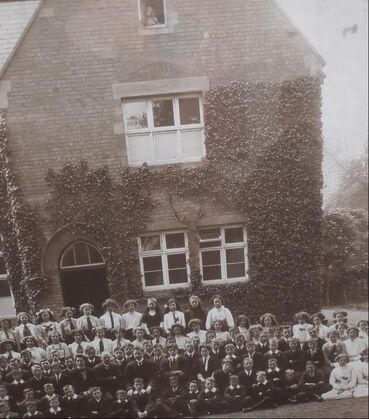

The school where I work has run a competition for students to write a story inspired by a thought provoking photograph of the students and staff from 1918, with a melancholy figure of a young girl watching from the high window above - said to be a 'ghost.' It reminded me of the year I spent as the Daily Ghost, writing a ghost story every day. Here's my ghostly story inspired by the photograph and the school's war memorials. Sometimes they come back, but they don’t find the one who loves them. Mr Edgoose told me that, on the day my childhood ended. Of course, I had no way of knowing, when I heard those words, that the day would be so momentous. It was another school day and I was spending an idle hour before my train would arrive, roaming the school corridors, as I would have done with Jack. Except Jack was not there anymore. He was crossing the Rhine in his tank, racing to Berlin, to win the War. It said so in his letter, that I carried in my breast pocket. I paused in front of the school photograph from 1918 and looked at the smiling faces from a hopeful time. School folklore said – and the younger boys believed – that the girl in the window was a ghost, watching over the masters and students gathered on the grass below. That was when I heard the tap-tap of Mr Edgoose’s cane and soon the teacher’s crumpled silhouette came into view. I remembered him teaching Latin to me in the First Form, but he was not seen outside of his room much, especially since what my mother called ‘the Great Blow.’ His boy Raymond had died on a Normandy beach. Raymond had been in the form below Jack. Mr Edgoose stood stock still when he perceived me there. He called to me, but his voice was a dry croak. Then he approached, his cane tap-tapping, slowing as he drew near and recognised me. “It’s Cheney, isn’t it?” “Yes, sir.” “Cheney Junior?” “Yes, sir. My brother is Jack Cheney.” He seemed apologetic, as if he had mistaken me for someone else. “You’re very tall, Cheney.” I nodded. People often commented. I was as tall as the boys who had been conscripted. He joined me in contemplating the photograph. Mr Edgoose smelt of tobacco and boot polish and the salty-sweet odour of gin that used to cling to my auntie’s dresses. “Sometimes they come back,” Mr Edgoose said. I didn’t take his meaning, but supposed he was thinking of Raymond. But then he continued: “I arrived in the school just a year after that photograph, A year after the Great War ended.” It was curious to hear it called ‘the Great War’ now that it was just the first and the Second War was grinding to its conclusion. “I did not serve,” he added, tapping his cane to his shin by way of explanation. “I thought, as a teacher, I would contribute to the peace.” His voice became thick and syrupy. I felt the childish dread that an adult was going to cry right there in front of me. But he recovered his composure: “I came up for an interview with the old Head Master. I was met by a young fellow named Robinson. Wilfred Jenkins Robinson, his name was. Charming young gentleman. I couldn’t judge if he were Sixth Former. There was a sorrow in him and a dignity that you don’t find in the young, but of course war makes us all grow old too soon. When he offered to show me around, I decided he must, like me, be a junior Master, so I allowed myself to be led here, to look at this very photograph.” The girl in the photograph was framed by an oblong of darkness. There was something inexpressively sad about her expression. She wasn’t contemplating the happy crowd below. Her gaze was upon a distant horizon, far across the East Anglian Fens, across the grey seas, across the broken fields of Flanders. “The girl in the window was his sweetheart,” said Mr Edgoose, interrupting my thoughts. “More, they were affianced, although secretly. She was a maid at the school. Wilfred Jenkins Robinson spoke movingly of their separation, of the promises they exchanged, before he left … before he left for …” I said, “Before he left for War,” and my voice was louder than I intended and the word ‘War’ echoed along the corridor and around the empty classrooms. I thought of Jack’s leave-taking. He didn’t have a sweetheart. I remembered how he tousled my hair. “You’re the man of the household now,” he said, adding, “the pater familias,” because he was top of the form for Latin. I made him promise to come back. “I’ll meet you after class,” he said, “when the school bell rings.” The echoes faded and the silence became oppressive. “Did they marry, Sir?” I asked. Then, when Mr Edgoose didn’t reply, I asked: “Wilfred Jenkins Robinson and his sweetheart. Did they marry?” Mr Edgoose considered the girl in the window but his vision, like hers, drifted far away, to the shores of Normandy. At length, he answered: “They did not. It was very tragic.” Then he added, “She took her own life. She threw herself from that window when she heard the news.” He turned away and there was something about his manner, the stoop with which he walked and the tremulous tapping of his cane, that I felt I could not let the conversation end there. I trotted beside him until we reached the doors to the Hall, where the bronze plaque marked ‘Dulce et decorum est’ recorded the names of the schoolboys who died in the last War. Mr Edgoose paused there. He stared at the list of names. “Sometimes they come back,” he said. “But they do not find the one who loves them.” “Like Wilfred Jenkins Robinson?” I said. “He came back for his sweetheart, the girl in the window.” Mr Edgoose drew a deep breath and the phlegm rattled in his chest. He said, “I wanted to ask him how it happened, how he learned of it, why he was still here in the place where she had died. The distance he had travelled. The journey from that place of death to this place of life. Only to arrive too late. But the school bell rang and the corridor filled with young boys. The Head Master arrived. He had been looking for me, it turned out.” He drew out his pocket watch and inspected the dial. “Sometimes they come back,” he said. “But not today.” I stood for a while, thinking of the girl in the window who had killed herself, and Wilfred Jenkins Robinson who had come back to marry her, but too late. Then I saw the names on the plaque; the names of the glorious dead of the Great War: J.C. Morrison, M.S. Page, J. Palfreyman … And underneath them: W.J. Robinson. I turned to Mr Edgoose for an explanation, but he had gone, though I never heard his cane tapping down the empty corridors. Those corridors were dark now. It was March and winter still haunted the school. Where was Jack, who should be with me? Then I remembered that Jack was in Europe and my train would be here soon.

I ran from the baffling name on the memorial plaque. I ran to the station and my train, wheezing and smoking in the dusk. All the way home I read and re-read Jack’s letter. I heard again Mr Edgoose’s promise: Sometimes they come back. At home, the telegram had arrived. “We regret to inform you …” My mother in tears, the dog unfed, the hearth unswept. It was the day my childhood died. As Jack had promised, I had become the man of the household. That night, I dreamed of Wilfred Jenkins Robinson making his long journey back from the Fields of Flanders. He crossed the great wasteland. He made a raft from barbed wire and sailed the grey seas. In the high window above the school, he brushed a tear from his sweetheart’s cheek. I saw them together, clinging to each other in that oblong of darkness. I awoke before down, weeping, and watched the grey light creep across the ceiling of my room. I told myself that Jack too would return. The wide lands of the Rhine would release him and the beaches of Normandy would send him home and he would be waiting for me, at the end of the school day, his smile turned to sorrowful dignity, but still Jack. There are times, all these years later, when I think I see him. The school bell rings and a figure passes my doorway, or a voice calls from the corridor, and I rise from my desk, scattering ink and student essays. But it is only a tall Sixth Former loitering or a boy’s cry from the schoolyard. I lower myself into my chair, my bones creaking. I examine my wrinkled hands. I walk to the window. Below me stretches the lawn where masters and students gathered for their photograph in 1918. I stand, framed by the window, and stare out across the East Anglian fens, the grey seas, to Europe, and further. I think of the girl in the window, stepping into that oblong of light, to meet her lover, as the Apostle promises, in the air. But I do not follow her. I will wait another day for Jack.

1 Comment

|

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed