|

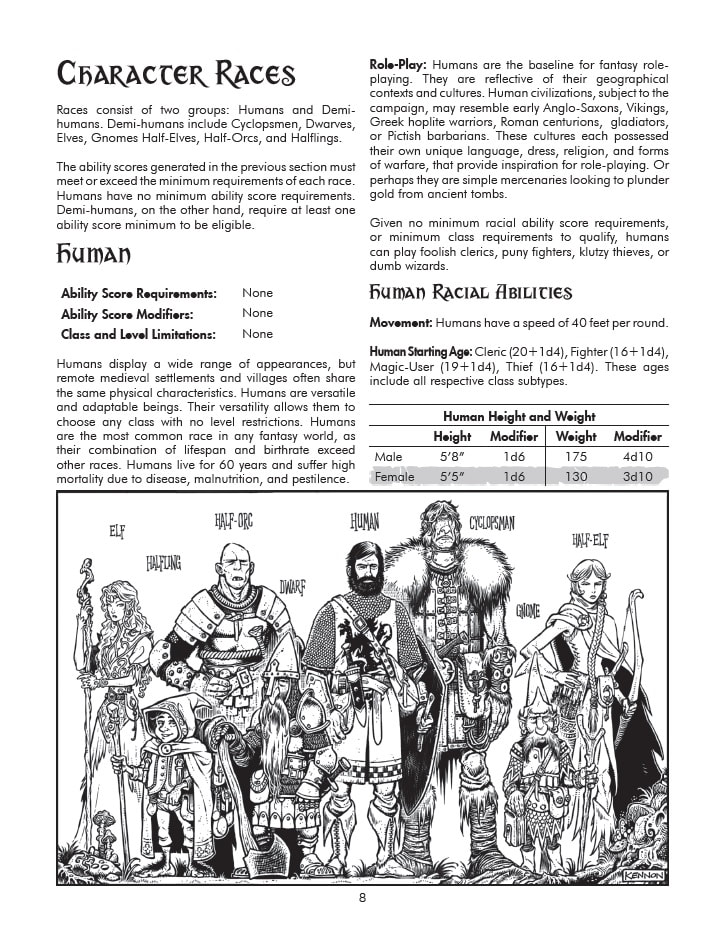

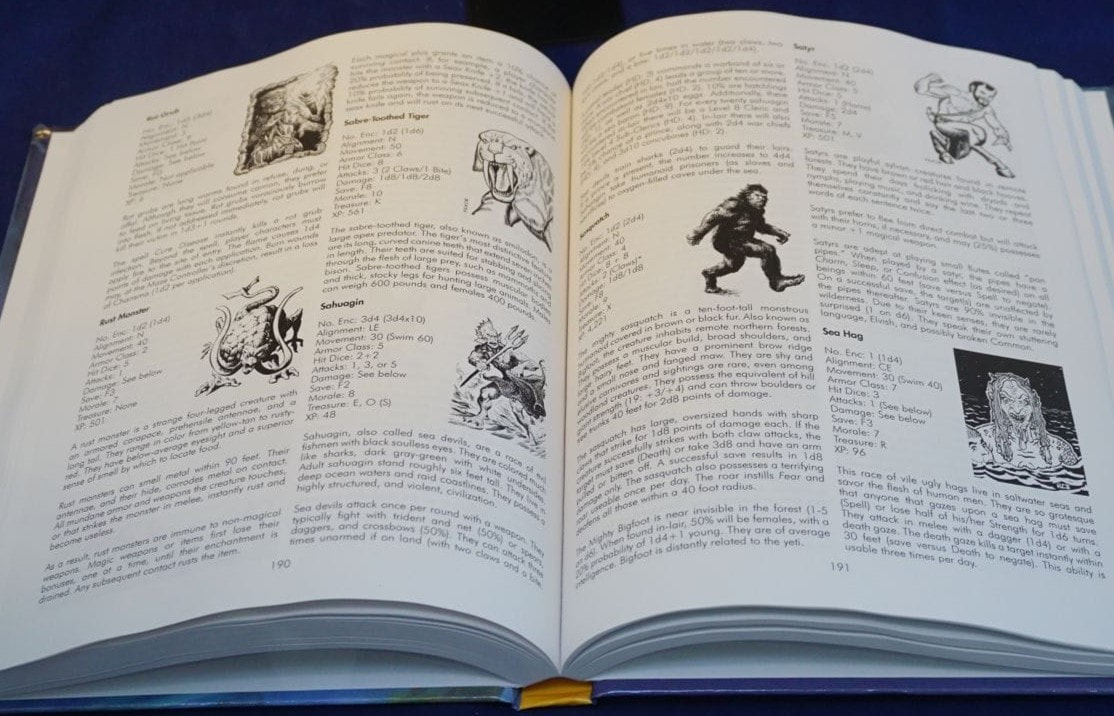

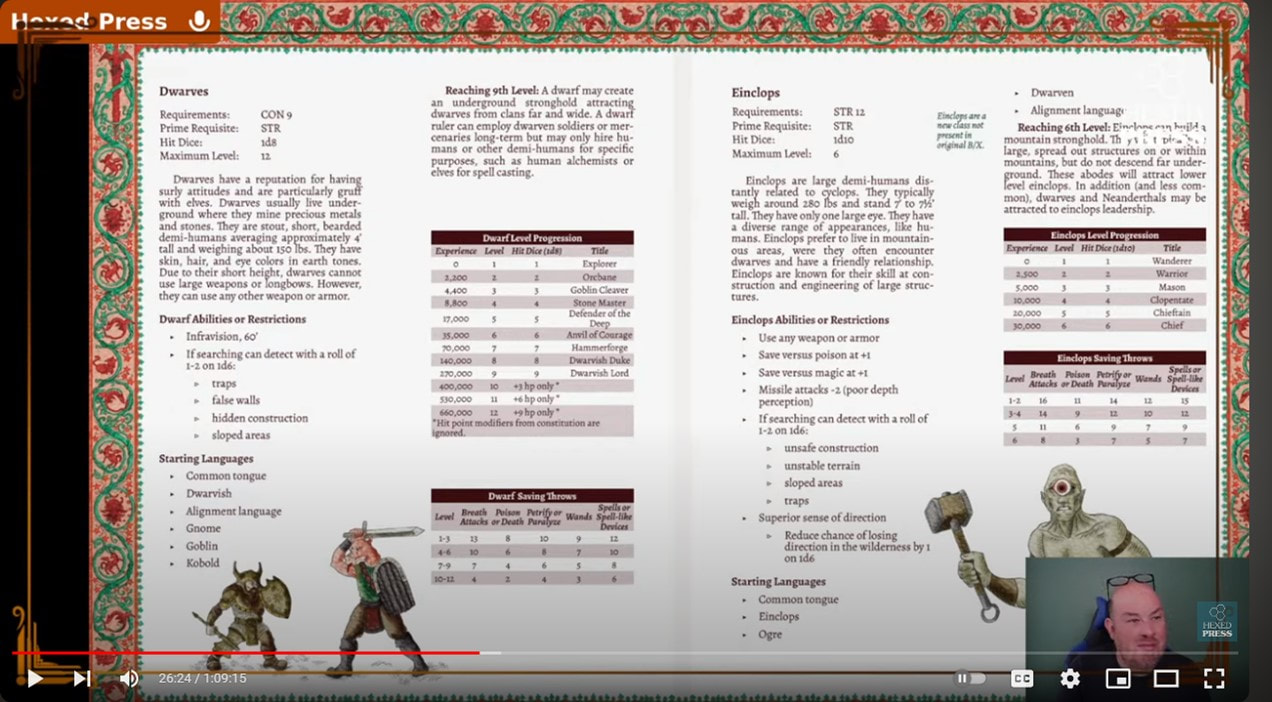

Most of us who love old school versions of D&D – or retroclones, as these rewritten versions of early D&D rule sets are termed - end up collecting them, but only using their particular favourite, if they use them at all. I’m a bit unusual, I suspect, floating between White Box Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game, Blueholme, and Labyrinth Lord. But look out, there’s a new retroclone on the block: Greg Gillespie’s Dragonslayer. Dragonslayer has its origins in the OGL Crisis that engulfed the roleplaying hobby – or at least, the OSR end of it – in 2023. You may recall that Wizards, who publish D&D, leaked a plan to revise the ‘Open Gaming Licence’ under which countless indie publishers had been creating D&D-adjacent material for 20 years. Much ink was spilled on what the original OGL did or did not permit and much speculation ensued over what new terms Wizards would impose on indie publishers. Several of the larger publishers took fright and announced plans to release their own Fantasy RPG systems that were carefully (and legally) distinct from D&D, while being fully compatible with their own D&D-adjacent products. A new generation of retroclones was a-borning, to use Stan Lee’s deathless phrase. Early out of the traps is Dr Greg Gillespie, who has become a one-man industry creating highly-regarded megadungeons. I’m a big fan of his Barrowmaze dungeon and have sent parties of adventurers into it under several fantasy rules systems. Given his investment of time, creativity, and profitable Kickstarter campaigns, in the megadungeon business, Dr Gillespie was hardly going to hand over a chunk of his profits to Wizards for the right to publish stuff based on D&D. So here he is with his own bespoke old school RPG, Dragonslayer. Whisper it: it’s still D&D really! The premise behind these retroclones has not, as far as I know, been tested in any court of law, but it wins universal acclaim in the court of public opinion, and it is this: you cannot copyright rules, only the distinctive imaginative properties those rules govern, and there’s nothing distinctive about concepts like elves, fighters, and fireballs. Therefore, Dragonslayer is really just 1980s-style D&D with certain properties removed or renamed. No mind flayers, ‘Phase Panthers’ instead of Displacer Beasts, and ‘Bigby’ has been renamed ‘Koweewah’ in all those high level ‘Magic Hand’ spells. It's more than that, though. Rewriting D&D from the ground up is a fantastic opportunity to ‘correct’ its original game's skews and stumbles and impress your own ludic philosophy on things. Old School Essentials is admired for the clean and clear way in which it assembles the jumble of rules and tables that comprise the game. OSRIC brings the mad labyrinth of AD&D together in one easily-referenced tome. Blueholme takes Holmes’s Basic D&D and extends it from 3rd to 20th level of play. Click images to link to these products on drivethrurpg The ludic philosophy is where things get a bit controversial. There are simple enough decisions to make about whether you are ‘cloning’ original ‘white box’ D&D, early Basic D&D (in its three iterations), or Gygax’s AD&D in all its Baroque glory. But some of these decisions get a bit … political. Are we going to persist in referring to Elves as a ‘race’ and capping their advancement as fighters or magic-users? What about sex-based ability caps? Your design decisions on these things are used by unkind critics to infer your viewpoint on everything from trans rights to who should have won the Second World War. As we shall see… Get On With It!To Dragonslayer, then. A single book, running to 300 pages, with striking cover art by industry legend Jeff Easley and interior art that more than lives up to the high standard he sets. It’s a beautifully laid out book, with crisp and slightly retro fonts, and materials curated to fit into single page spreads where appropriate. But then, if you are familiar with Barrowmaze and other Gillespie products, you will expect no less. It’s not cheap but you can see where the money went. Appetisers: races and classesThe introduction sets out the ‘Six Tenets of Dragonslayer’ which amount to a familiar OSR manifesto: ordinary heroes, rulings not rules, the DM (sorry … Maze Controller!) is absolute sovereign. Roll a character using the ‘Classic Six’ attributes: roll 3d6 seven times and assign as you like. Abilities follow the Basic D&D gradations (13-15 grants a bonus, 16-17 a great bonus, 18 an amazing bonus, likewise penalties for scores below 9). First level characters start with maximum Hit Points. There’s Descending Armour Class and if you’re one of those people who never understood THACO, well, I have some bad news for you later. Now for Races – and it’s old fashioned Races, not lineages or heritages or (shudder) ‘species.’ I’m British, so the R-word doesn’t connote the Satanic tang for me that it seems to have for some Americans. There are half-races here too – Half-Elves and Half-Orcs. Yes, I’m familiar with all the arguments about this. I quite admire the way Blueholme Journeymanne comes out and says: your PC can be any type of creature you like, even Thri-Keen insect people! But part of the 'old school experience' for many players is adapting yourself to the very particular imaginative contours of the game as it was in the ‘70s and ‘80s. So Half-Elves are a thing, but Half-Dwarves are not. There are some missteps, such as the big, dumb, one-eyed Cyclopsmen. Surely 'Cyclopsfolk' you say? Nope, Cyclopsmen. Deal with it. If you want to start deconstructing the game for sinister sentiments, then you start here, because these creatures are former slaves with limited IQ. They’re an unhappy inclusion (and in terms of the culture wars, a bit of an unforced error) since they have no prototype in early versions of D&D – and Half-Orcs already fulfil the big’n’brutal role. I guess they were part of Greg Gillespie’s homebrew campaign and he included them out of gratitude for the fun they brought to his table. I wonder if this was wise, given the proclivities of some critics to sniff ideological taint in things like this. The races all get randomised starting ages, height/weight tables, ability modifiers, their own base movement rates, and suggested languages for high-Intelligence characters, as well as some roleplaying hints. Darkvision is here, rather than the classic infravision, which may or may not please you. There are quirks. Gnomes have an affinity with being illusionists, so their spells last +3 rounds. It’s a bonus that will rarely make much difference to anything. Elves, meanwhile, enjoy +1 to hit with the longbow. Elves have lost their immemorial perk of being fighter/magic-users who can wear armour and cast spells. Dragonslayer seems to be a bit hostile to the idea of multi-classed characters. The concept gets a brief paragraph on p39, amounting to ‘It’s up to the GM (sorry - 'Maze Controller') whether it’s even allowed, but if it is, you get stuck with the most punitive armour restrictions of the classes you are combining.’ I’m deeply loyal to the idea of Elves in armour casting spells. My first ever D&D character (for Holmes Basic, back in 1978) was an Elf called Tristan with a Sleep spell. It seems to me there are two interesting ways to house-rule Dragonslayer. Maybe let all Elves use longbows, regardless of their character class, rather than the bonus ‘to hit’ which pretty much only benefits Elven fighters. Alternatively, let Elven fighter/magic-users wear armour (maybe limited to chain mail) – and why not let the Gnomish thief/illusionists wear leather armour while you’re at it – instead of these piddly little bonuses. But that’s just my 1sp. The character classes are incredibly well set out and the innovations here are astute. Each class fits on its own splash page, with saving throws, spells, class-abilities, and starting funds, as well as a set of ‘fast packs’ to equip starting characters. Clerics with Wisdom 15 get an extra 1st and 2nd level spell – as do magic-users with Intelligence 15+. Magic-user starting spells are rolled from an offence, defence, and a utility, with Read Magic and Detect Magic as standard. Clerics can trade in any spell they’ve learned to cast Cure Light Wounds and magic-users/illusionists can do the same to cast Read/Detect Magic. Druids don’t get this very sensible bonus – but they do start with 2 spell slots at first level, so I suppose they’re OK. Fighters get a ‘cleave’ power that gets them extra attacks whenever they kill an enemy in combat – an innovation that certainly adds momentum to combat. Thief powers strike me as enhanced: Move Silently 33% and Hide in Shadows 25%, compared to 23%/13% in Labyrinth Lord, and a ‘why-even-bother-trying?’ 15%/10% in AD&D back in the day. One alteration set me thinking. Dragonslayer’s clerics turn undead on a d20 (like AD&D) but can only attempt turning three times in a day. Pick your battles, right? I can see the rationale for this. Lots of scenarios won’t feature undead at all, or just occasional instances (wandering monsters, a dungeon room that’s a crypt), so often this restriction won’t matter. But if you’re running an undead-themed dungeon – like, er, Barrowmaze – then clerical turning becomes the boring default for every encounter. This forces PC clerics to weigh up whether undead can be dealt with by violence and use turning only after careful deliberation. Turn, Undead, Turn by CaptainNinja on DeviantArt There are two unexpected classes. Monks appear, but radically redesigned. These are not the Kung Fu martial artists of AD&D; no, they are very much medieval-style mendicants, more Friar Tuck than Grasshopper. One of these Monks is not like the other one! They even start off knowing ‘Ancient Common’ (which, I guess, means Latin). They don’t wear armour but their AC improves every level. They get combat feats with a quarter staff. They can chant. At higher levels, they get clerical spells and turning undead but also do Comprehend Languages at will. They feel a bit one-note to me, but at least they’re coherent. Barbarians are back, but these are the ‘Asbury Barbarians’ (referring to Brian Asbury’s prototype for the class published in White Dwarf long ago and discussed here). They are limited to light armour, fly into berserk rages, and get a few thief abilities, but they scorn magic. It’s a classic build and this seems to be a coherent iteration of it. The Main Course: spells, monsters, magic items - and a few rulesI won’t dwell on the spell lists. They seem to be the AD&D-via-Labyrinth Lord canon, with some renaming to throw the lawyers off the scent. The descriptions are even more concise than Labyrinth Lord, but I wish there were page references for them – or an index!!! – and this complaint recurs with the monsters and magic items. The monster bestiary is extensive. Dragons get good treatment (complete with a multi-headed ‘Mother of Dragons’ – ahem) and the coverage of Demons’n’Devils is refreshingly candid. I guess you can’t copyright Mephistopheles, but I’m surprised to find ‘vrock’ appearing as the lowest order of demonkind – these infernal naming conventions have been imported wholesale from the AD&D Monster Manual rather than reinterpreted. Presumably Dr Gillespie took good advice on that – or perhaps he figures that family-friendly Wizards aren’t going to get involved in a legal spat over legal ownership of demons!!! Oh, and the picture of a Hobgoblin on p170 is a delightful homage to David Sutherland’s iconic ‘samurai’ style for them. The magic items list is particularly good – unsurprising, since Gillespie shows himself to be a prolific inventor of magical gewgaws in Barrowmaze. Intelligent swords get a careful treatment, Dhurinium (mithril) armour is linked to the imagined setting in exciting ways, and there are lovely tables for randomly generating hordes – again, no surprise if you’ve seen Barrowmaze. What does come as a surprise is just how short the main rules section is: a couple of pages covers combat, dungeon exploration, and saving throws. This is testimony to how well-designed earlier sections were, drawing together the key information into the treatises on character classes and abilities, so it doesn’t need to be repeated here. You need a 20 to hit AC 0, and you get modifiers to make that easier as you go up in levels, rather than having complicated tables for each and every class. Strangely, the same minimalist approach is not adopted for saving throws. Missed opportunity there, I think. One effect of this is to de-power monsters, who also hit AC 0 on a 20 and follow the same bonuses as fighters, which means +1 to hit at 3HD and with every HD thereafter. This means 2HD monsters are no better than starting characters, which is bad news if you’re a Gnoll. The Dessert: good adviceThe last 30 pages offer some fantastic resources, such as advice on dungeon design, wilderness campaigns, excellent random tables to map and stock dungeons, and a cute time tracker with rest breaks and wandering monster checks included. So, Should You Buy It?Recommending Dragonslayer is complicated – it depends on what you’re looking for. If you collect OSR retroclones, then you’ll want to add this handsome book to your collection. If you are intending to play a retroclone RPG and you wonder if Dragonslayer might be the best purchase, then there are things to consider. Dragonslayer is quirky. It’s full of departures, great and small, from the pristine D&D rule set of yore. I’m not just referring to the regrettable Cyclopspersons or the way the game hybridises elements of Basic D&D with the classes and spells of AD&D. There are all sorts of ways in which Dragonslayer differs from the game that people were playing in 1978. Thieves actually have a decent chance of doing something useful at 1st level, for instance. But if you want to dust off some classic modules, like say, B2: The Keep on the Borderlands or G1: Steading of the Hill Giant Chief, then perhaps you want that authentic early D&D experience without the innovations. May I direct you instead to Blueholme for B2 or OSRIC for G1. Or Advanced Labyrinth Lord if you want the hybrid rules without the novelties. It's only fair to add that you can pick up these earlier retroclones (with their royalty-free art and functional layouts) far cheaper. If you’re not looking for the authenticity, but you are shopping for an OSR rules set with a contemporary flourish, then Dragonslayer is a strong contender. However, there will be a post-OGL revised edition of Labyrinth Lord later this year, which author Dan Proctor promises will also break with the D&D mould in exciting ways; it looks rather beautiful and also has a cyclops PC race, if that’s a weird deal-breaker for you. Hexed Press previews Labyrinth Lord 2e The third consideration is whether you use Greg Gillespie’s excellent megadungeons. If you are playing Barrowmaze, for example, then Dragonslayer fits it like a glove. Indeed, several features of Dragonslayer seem to have emerged specifically in response to the design decisions in those dungeons (like the reconsideration of clerical turning). If you want to get into those big, daunting, exciting dungeoneering projects, then Dragonslayer is a no-brainer. Get on board. For me, the charm of Dragonslayer is its 'lived in' feel. Despite the speed with which it was brought to press, it doesn't feel rushed. You very much sense that this is the consummation of Greg Gillespie's own D&D campaign, with house rules and good practice developed over many years. Everything feels lovingly crafted and bedded in through recurring use. Despite being a new game, it feels like an old one, and that's praise that goes to the heart of what makes a retroclone appealing.

0 Comments

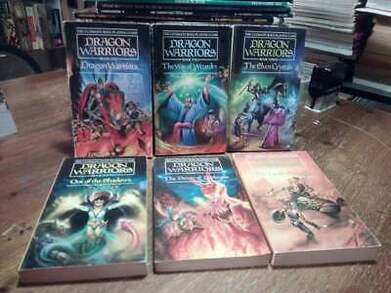

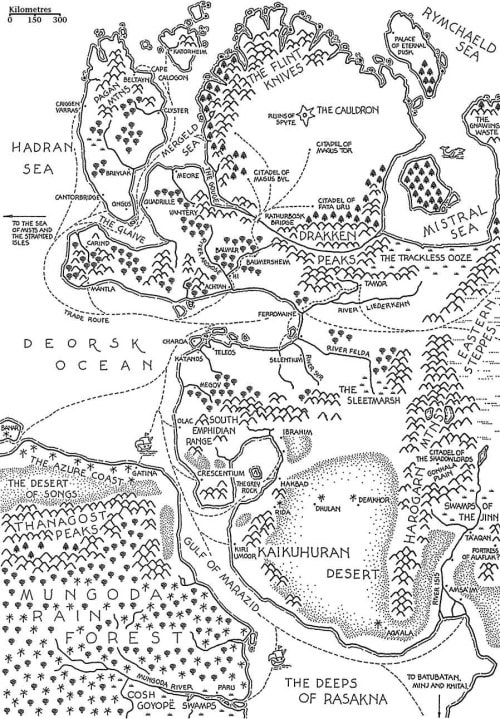

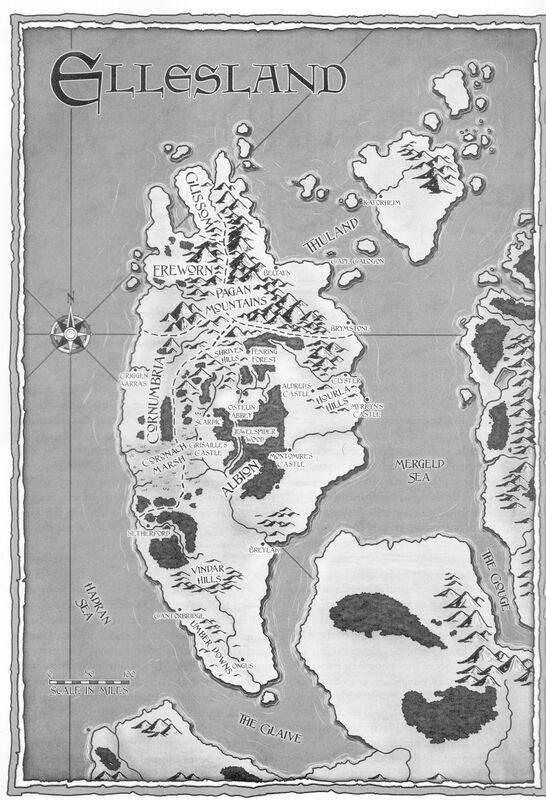

I finally got to play Dragon Warriors. You're thinking, "Wasn't that a Nintendo console game?" Well, yes, it was, but I'm talking about the British RPG from the 1980s. The original '80s Dragon Warriors RPG in cool paperback format Dragon Warriors was created by Dave Morris and Oliver Johnson in 1985, slipping in just at the end of the 'Old School' era of roleplaying games. DW bucked a number of trends. For one thing, it was a simple rules system, only marginally more fiddly than the BECMI Dungeons & Dragons rules that offered a stripped down alternative to AD&D and are so beloved of OSR purists today. This, at a time when RPG design was tending towards complexity, with systems like Rolemaster and Harnmaster offering (to my mind, excessive) realism through a plethora of tables. DW's other distinguishing feature was its format: published by Corgi books in the classic 178mm x 110mm trade paperback size. This meant the game was delivered to you in a modular sequence. The first book, Dragon Warriors, introduced core rules with Knights and Barbarians as PCs. If you wanted magic, you needed Way of Wizardry for Sorcerers and Mystics. The Elven Crystals provided linked scenarios, Out of the Shadows added Assassin PCs, The Power of Darkness added Elementalists and The Lands of Legend developed the campaign setting (a world called Legend) and Warlock PCs. The books retailed at £1.75 back then, which was cheap compared to other games normally priced at £10-12 . But then again, other '80s RPGs tended to come in a box, with a starter scenario or screen, and to acquire all of DW you would need to spend £9.50, so perhaps it wasn't such a saving. On the other hand a young gamer could acquire Dragon Warriors gradually, in pocket money sized instalments, rather than needing to wait until Christmas or a birthday for the substantial gift of a £10 game. (If you want to translate into today's money, multiply mid-'80s prices by three.) The paperback format probably made sense to Corgi, because the Fighting Fantasy game books were still printing money for Puffin Books and Corgi adopted a similar look with Dragon Warriors, hoping for some crossover purchases. It was not to be. Dragon Warriors won warm praise from critics and gathered a devoted fan base, but it never secured a place at the top gaming table. There were many reasons. It was quirky British at a time when American culture dazzled. It was conventional fantasy at a time when interest was rising in SF, horror and book/film tie-ins. It was simple when complexity was fashionable. Changes in print technology would soon make RPG rule books into glossy hardback artefacts resembling coffee table talking points and DW's paperback format came to look childish and naff by comparison (but is beloved by collectors now for that very reason). Dragon Warriors and the '90s competition. 'Game over, man!' I never played DW when it first appeared. I was starting university and moved past Fighting Fantasy and pocket money sized instalments didn't appeal the way it would have done a couple of years earlier. But I noticed it, especially the adverts that promoted DW's authentic medieval and faerie themes. I remember being particularly drawn to an advert for the game that promised a RPG setting in which Elves were not cosy woodland party-goers, but alien entities who have no souls! DW was rescued from oblivion by Mongoose back in 2009, who brought the six paperbacks together as a single volume. When that lapsed, DW was rescued again by Serpent King Games and their edition, as well as many more supplements and scenarios, can be bought at drivethrurpg. How Does It Play? (but don't bore me ...)I'll try not to! You create your character by rolling the familiar 3d6 for Strength, Reflexes, Intelligence, Psychic Talent and Looks. As is traditional for old school RPGs, 'Looks' has no mechanical value in the game and serves as a dump stat for all right minded people. The important stats are Attack, Defence, Magic Attack and Defence, Stealth, Perception and Evasion. These are dictated by your character class and (slightly) modified by extreme score in Strength, Reflexes, etc. (but not Looks, obviously.) Hit Points are rolled with a modifier based on your class, with Barbarians getting the most Hit Points, as is only right and proper. The basic mechanism is to roll a d20 and score under your stat. If it's a conflict, you deduct your opponent's Defence or Magical Defence from your stat. If it's a ranged attack, instead of deducting Defense you get a penalty based on their range, size and speed. A 1 always hits. That's it. Well, not quite. Weapons do a fixed amount of damage, like 4 for a dagger or 6 for a morning star. This is modified for very high/low Strength (but not Looks!). You then roll to bypass armour. Each weapon has its own Armour Bypass Die (a d4 for a dagger, a d6 for a morning star) and you have to roll it and match or exceed the armour rating (4 for full mail, 5 for plate armour) otherwise you do no damage at all. On top of that, a shield gives a simple 1 in 6 change of negating all the damage. This means you end up imitating D&D by rolling a d20 'to hit' then a weapon die, but the weapon die is really a second 'to hit' roll versus armour. Fixed damage takes some of the unfairness out of dicey mechanics, but it does make combat somewhat predictable. Heavily armoured PCs have a definite edge over monsters. The combat feels a bit clunky and unresponsive to dramatic improvisation, but it captures the brutal tone of medieval melee and it gives armour the right sort of value. There are Spell Lists and some of the spells are quite distinctive. Magic using characters can cast any spell (no Spell Books, which is disappointing) but have to spend Magic Points (MP), which recharge once a day. Mystics are a bit different; instead of MP they have a push-your-luck mechanic which can result in losing all magical power for the rest of the day. There are a few fiddly details. Some rolls are made with 2d10 instead of a d20, which additional penalises low scores and further rewards having high scores. I can't quite see the point of this. In a nutshell: It's a fairly boilerplate RPG rules set with a heavy focus on fighting, no social mechanics to speak of and a fairly gritty feel to it. Character classes are prescriptive but are nicely locked into the medieval setting. You get to choose skills at higher levels, but otherwise characters of the same class are as undifferentiated as D&D - perhaps more so, because draping yourself in goofy magic items is less of a thing for DW. What's the Setting Like? (please be brief)DW's biggest draw is its world and the tone created by that setting. The world is called Legend. Legend has more than a passing resemblance to 13th century Europe, with Ellesland (NW corner) having a kingdom called Albion - where (with the patriotic perspective we expect) the campaign is assumed to start. From there, PCs can explore such exotic and threatening places as Chaubrette (France), Algandy (Spain), the New Selentine (i.e. Holy Roman) Empire and on south and east to caliphates, sultanates and emirates and Mungoda, which is plainly Africa. I'm sure Edward Said would have turned in his grave, if he wasn't alive and well at the time, having published Orientalism just a few years earlier, denouncing this sort of other-ing and fetishizing of African and Middle Eastern culture. Once we've had the mandatory cringe at all this eurocentric bias and cultural appropriation, let's put this in a RPG perspective. Dragon Warriors was in good company. Gary Gygax ran his original D&D campaign in a fantasy world that was a map of North America with the names changed. Expert D&D, published just a couple of years before DW, introduced the Known World setting, later named Mystara; this spawned a set of gazetteers in the late 1980s, most of which explicitly modelled fantasy realms on historical civilisations - for example, Ken Rolston's The Emirates of Ylaruam (1987) bundles the Islamic Middle East into a single fantasy realm. At around about the same time, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay was developing the Old World setting, which pastiched Michael Moorcock, H P Lovecraft and Renaissance Europe into a distinctive fantasy world. (And of course, 1996 George R R Martin published Game of Thrones.) It's to DW's credit that it treats Legend as more than a gauzy historical backdrop, but rather expects players to lean in to its culture and cultural conflicts. Knights are expected to live by the feudal code and Barbarians and Elementalists are explicitly the warriors and mages of the northern and eastern expanses. The scenarios go out of their way to illustrate medieval norms and assumptions about class, nationhood, honour and the supernatural. Faerie is another feature of this setting and DW strives to evoke a numinous and threatening feel for the Fae: beautiful but alien, feared, fickle, otherworldly, uncanny. Very different from the humdrum Elves of D&D and Warhammer, but not unlike the Others/White Walkers of Game of Thrones. My friend Simon Barns reminds me of other '80s games that explored a fantasy/historical setting. Chivalry & Sorcery rather beat you over the head with its historical verisimilitude and DW is a light-footed, free-spirited nymph by comparison. Pendragon excels at this sort of roleplaying, but only in the Arthurian theme and with the convention that you all play Knights. So, Are You Going to Play It?No, I don't think so. There's an introductory scenario in the revised rulebook called The Darkness Before Dawn which I ran with a group of friends. It's a fine scenario, illustrating feudal duties, community tensions and faerie malevolence. Everybody enjoyed themselves. But the session illustrated both the strengths and shortcomings of Dragon Warriors as a rules set. Character creation is quick but rather unsatisfying. Put simply, you are your character class. The background tables prompt you to deviate only slightly from the medieval stereotype (our PC Knight was the son of an ink maker and must have been knighted as a mercenary). Combat is similarly clunky - not laborious or longwinded or fiddly, just lacking in drama. The magic system is solid and might have seemed very fresh and rational compared to the lottery that is D&D, but again lacks colourful moments. Judged as a OSR product, DW feels as if its moment has passed. A good comparison might be that other 'fantasy heartbreaker' that I love: Forge Out of Chaos (see blogs passim). Forge and DW offer a similar departure from old school D&D without questioning its core assumptions. They both retain the 3d6 characteristics and the roll-a-d20-to-hit combat system. But Forge has more interesting quirks, like weapons notching, time out to repair armour, harmful side effects from spells and a distinction between damage done to armour and damage done to its wearer. The crucial problem with DW is that the stuff that makes it so distinctive - the twilit, Celtic-themed Faerie vibe - isn't part of the rule set at all. The PCs aren't faerie themed - they don't have mystical geisa binding them to tragic dooms, they can't go into warp spasms, they don't have Fae heritage or the second sight, you can't roll to be the seventh son of a seventh son. The magic system is sturdy but generic: there are no faerie themed spells, you can't tap ley lines, open portals at standing stones, commune with river goddesses or learn someone's True Name. All of which adds up to this proposition: I explore the world of Legend and DW's excellent scenarios without having to use the Dragon Warriors rules set, because the rules set is no necessary part of what makes the setting and the scenarios so good. If I wanted to emphasis gritty combat and white-knuckle survivalism, I'd use Forge: Out of Chaos; if I wanted to retain the simplicity and the sense of being ordinary mooks in a big bad world, I'd go with Warlock!. If I just wanted to tell wild fairy tales in a romantic medieval setting, I'd use Blueholme or another D&D retroclone. Warlock! and Blueholme are available at drivethrurpg (click the images) but Forge can only be found in (vintage) physical editions at the moment - albeit inexpensive ones Sounds Like You're Being a Bit Harsh ...Maybe I am. I can certainly see why people who discovered Dragon Warriors in the '80s stayed loyal - and I can see why DW might be an exciting discovery for someone delving into RPG products of decades past. It's probably the best of the 'lost' RPGs of that era and, if it were categorised as one of Ron Edwards' 'fantasy heartbreakers' then it is an exceptional one. I'm judging DW from my own perspective, of course. If I run a fantasy RPG, it will always be in a historical setting or one inspired by a historical era. Faerie is a big influence on my imagination and I represent Faerie in my games very much as Dave Morris & Oliver Johnson advocate in Dragon Warriors. I prefer low-key fantasy RPGs where wounds, trauma, supplies and the like all matter. And because of this, I'm disappointed to find Dragon Warriors isn't offering me anything except exhortations to roleplay in the way I already do, in a world very like one I would create myself, and a rules set that has no distinctive advantages over other OSR or fantasy heartbreaker games I already own,. In other words, by the time I finally got round to reading Dragon Warriors, it was too late. The moment has passed. The passion isn't going to ignite. We're in the friendzone, DW and I. But you, Dear Reader, maybe you're different. Maybe you've never done a fantasy RPG in a historically inspired setting. Maybe this Faerie theme thing is new to you. Maybe you're wanting to try one of these 'old school' RPGs and don't know which of the many out there to begin with.

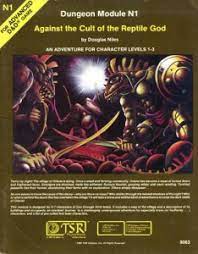

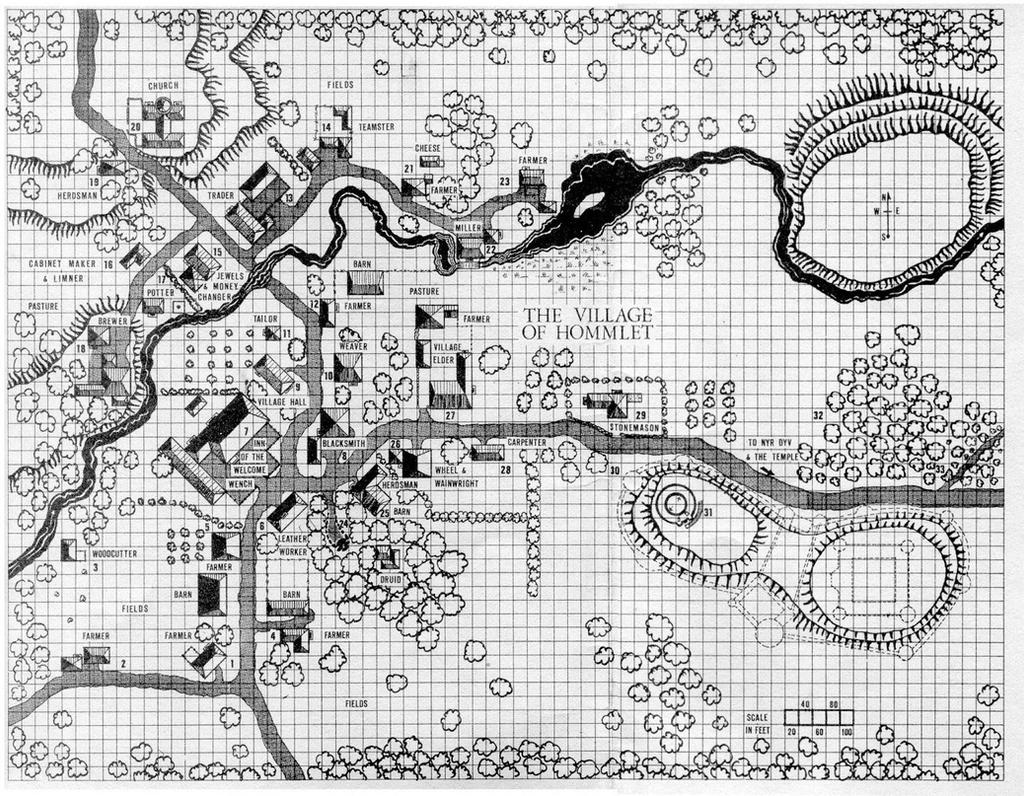

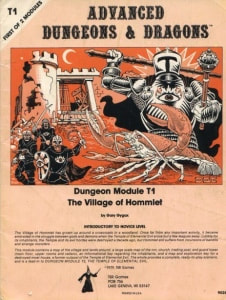

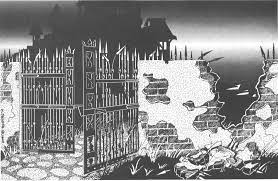

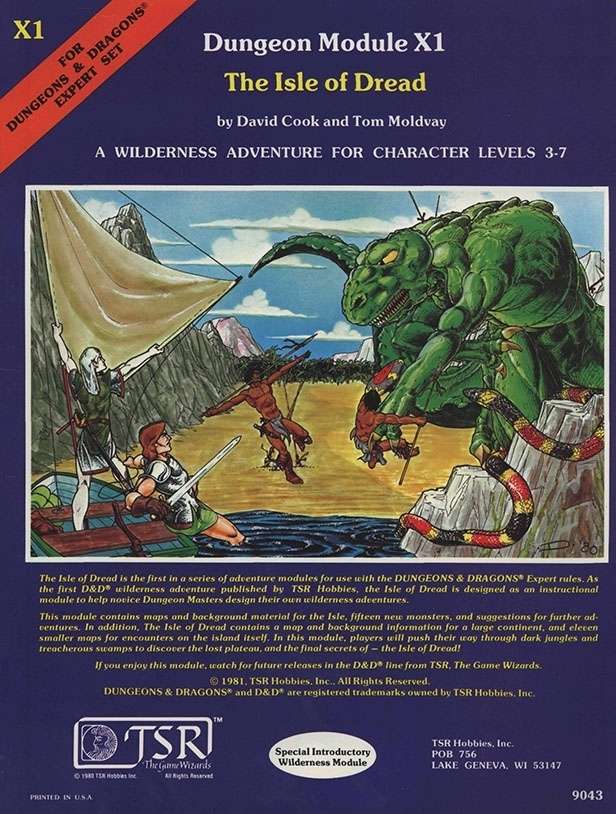

I reckon, if two out of the three above apply to you, then Dragon Warriors will blow your mind. I think it would have blown mine if I'd discovered it back when I was 18: with her moody Celtic beauty and quirky medieval style, Dragon Warriors is the one that got away. SPOILERS AHEAD: Fen Orc and Swamp Goblin dissect the classic 1982 AD&D module 'Against the Cult of the Reptile God.' My good friend Swamp Goblin and I have decided to put out a series of video reviews focusing on the RPG products that inspired us. Here's our first; my video production skills are pretty basic, but they're only going to get better. AD&D module N1: Against the Cult of the Reptile God came out in 1982. It was written by Douglas Niles, a former English teacher who bashed this out in 4 weeks: it was his first assignment as a designer for TSR. Niles went on to design other RPGs, like Star Frontiers: Knight Hawks and Top Secret: SI, had a big hand in creating Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms and authored a ton of novels. Reptile God is fondly remembered - and deservedly so - and a particular delight is the way it subverts the expectations of 'Golden Age' or Gygaxian D&D. In the early template, the village acts as a base for the PCs to raid a nearby dungeon. This gets its definitive outing in 1979's T1: The Village of Hommlet. Sure, there are dramas in Hommlet: you can go around gathering clues, you can recruit NPCs to your party, there are a pair of evil dudes who will spy on you for the nearby Temple of Elemental Evil, there are sectarian tensions between Druidists and Cuthbertites. But Hommlet is fundamentally static and benign and it's up to the PCs to make things happen there - or not, as they choose. You can see the influence of Hommlet on Niles' design of Orlane. There are rectangular houses on neat patches connected by public roads and screened by attractive trees. It looks like no medieval town ever; rather, it's a sort of idealised American frontier settlement, somewhere north of Walton Mountain and south of Avonlea, not far from St Petersburg, Missouri. This sort of American idyll, passed off as pseudo-medieval Europe, is very common in fantasy RPGs. You can see it in Greg Stafford's Apple Lane (1978, one of the first RuneQuest scenarios) and I do a deep dive on Mark Kibbe's World of Juravia over here. I mention in the video that an interest in what lies beneath the surface of small town American life has a long pedigree in American literature. I forgot to mention the link cited by Stephen King himself: Grace Metalious' 1956 novel Peyton Place which explores lust, incest and murder in a sleepy New England town. It's the close resemblance of Homlett and Orlane to idealised American communities - rather than actual medieval ones - which drives home the themes of corruption and secret conspiracy so effectively. Niles builds on Gygax's wholesome template in several ways. For a start, he's a better writer and each location is introduced with snappy read-aloud captions that establish more than the size and shape of the property. Attentive players will pick up on tell-tale details of chaos and neglect that indicate (often, but not always) the influence of the Reptile Cult. Niles takes the implied drama of Hommlet and makes his setting fully dynamic. Over a period of days, the Cult will abduct and brainwash the free-willed villagers, in a particular order. This is a community that changes while the PCs are here and if they do nothing at all they will still notice events going on. Niles is sometimes credited with introducing a more investigative, less combat-orientated approach to D&D. Sandy Peterson's Call of Cthulhu RPG came out the previous year (1981) and it's hard not to see the thematic links here - although Niles would have had his work cut out to read and digest Call of Cthulhu and then bash out this Cthulhu-esque module in the time available, so it is perhaps a coincidence. Another possible coincidence is that 1981 saw the release of the first British AD&D module, U1: The Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh, by Dave J. Browne with Don Turnbull. Saltmarsh surely beats Reptile God to the punch when it comes to delivering an investigative AD&D adventure. I'm not sure whether Niles would have been aware of the material being created by TSR (UK) and - again - the time frame doesn't leave much scope for a direct influence. But in any event, Niles' Orlane differs from Saltmarsh in fundamental ways. For a start, Saltmarsh isn't mapped or detailed: it gets a pretty lightweight description: Interesting: the World of Greyhawk location puts Saltmarsh south of Orlane, in the neighbouring Kingdom of Keoland. OK, it's a few hundred miles away, but the same general region. Moreover, the whole point of Module U1 is [SPOILERS] that, despite all appearances, there isn't actually anything supernatural going on - whereas in Orlane, despite the superficial prosperity, there is an occult menace at work. U1: Sinister Secret of Saltmarsh is not an adventure I've ever loved. It feels anticlimactic to me, far too invested in atmosphere and not enough drama and, despite all the investigation and clue-finding, it ends up with a massive fight that can easily overwhelm a low-level PC party (the NPC magic-user has a Sleep spell, ferchrissakes). The secret is not particularly sinister - or even particularly secretive. One thing you cannot accuse Saltmarsh of, though, is being too American. It's all fog, brine, fishy smells and a general sense of murkiness. The later scenarios in the U-series bring in reptile-people (Lizard Men, Sahuagin) and their cults, but there's a complex and realistic political situation unfolding: they're not just 'monsters.' Meanwhile, N1: Against the Cult of the Reptile God picked up critical plaudits, but never spawned a sequel. The N-series turned out to be N-for-Novice: a string of modules supposedly designed for starting characters, not a series developing the region of Orlane, the Rushmoors and the fallout from the destruction of the Cult. The next N-module came along in 1984 and Carl Smith's N2: The Forest Oracle is (not entirely unfairly) pilloried as the worst TSR module ever. In particular, it's condemned for its sloppy and ineffective writing - which only throws Douglas Niles' strengths as a designer into sharper relief. In the video review, Swamp Goblin and I discuss different ways that N1 could develop after the destruction of the Cult. Maybe Module alt-N2: Revenge of the Goddess Merikka, is something I'll have to write myself ... In the meantime, our next deep dive review will be the oh-so-problematic Module X1: The Isle of Dread.

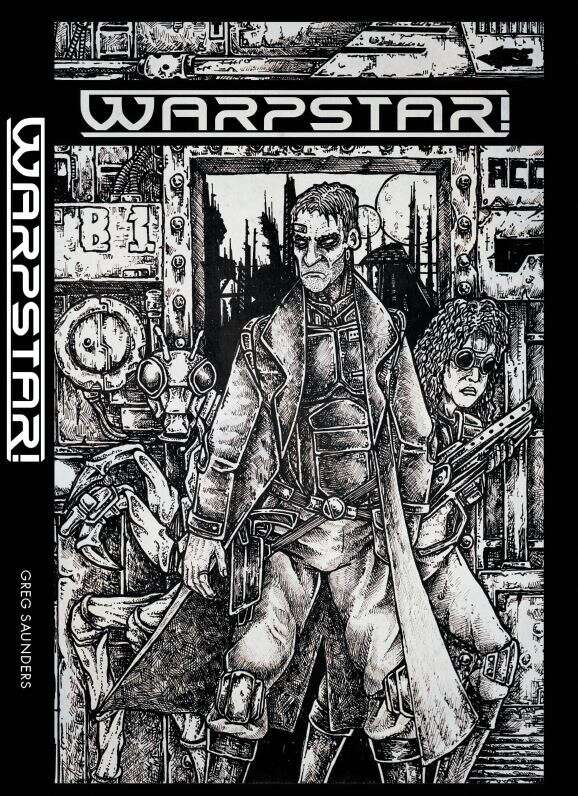

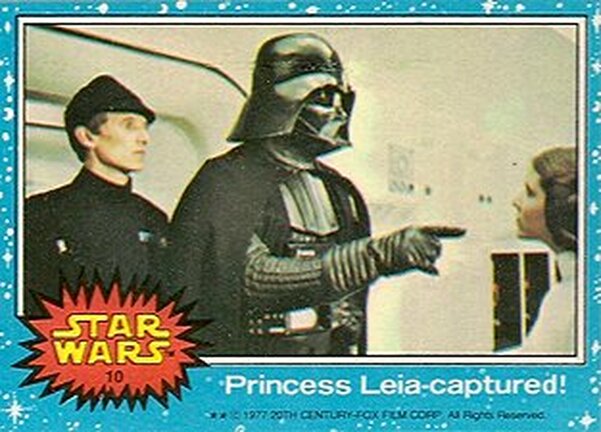

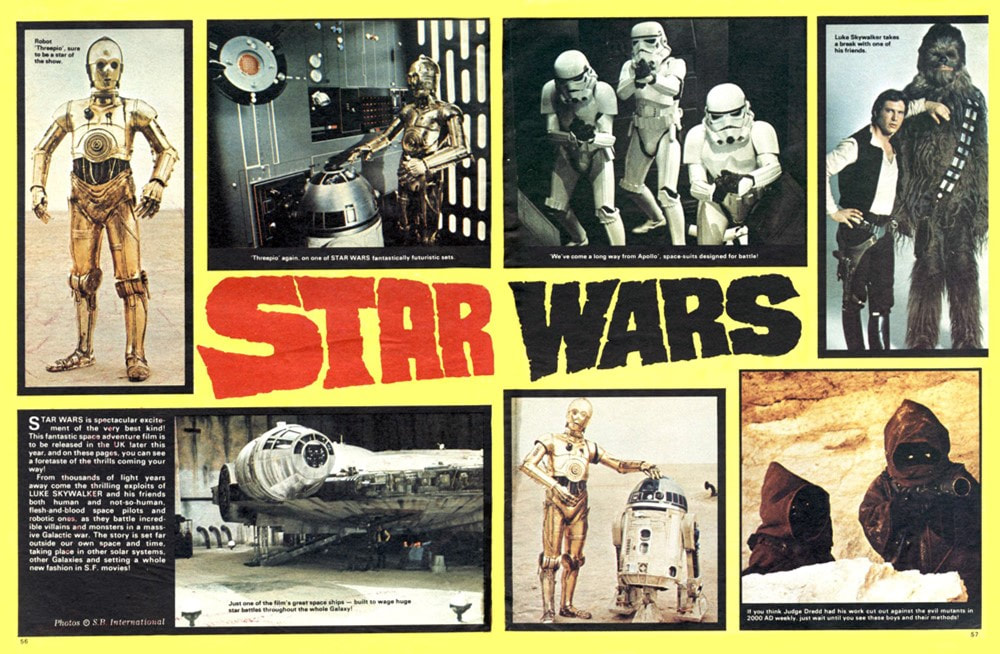

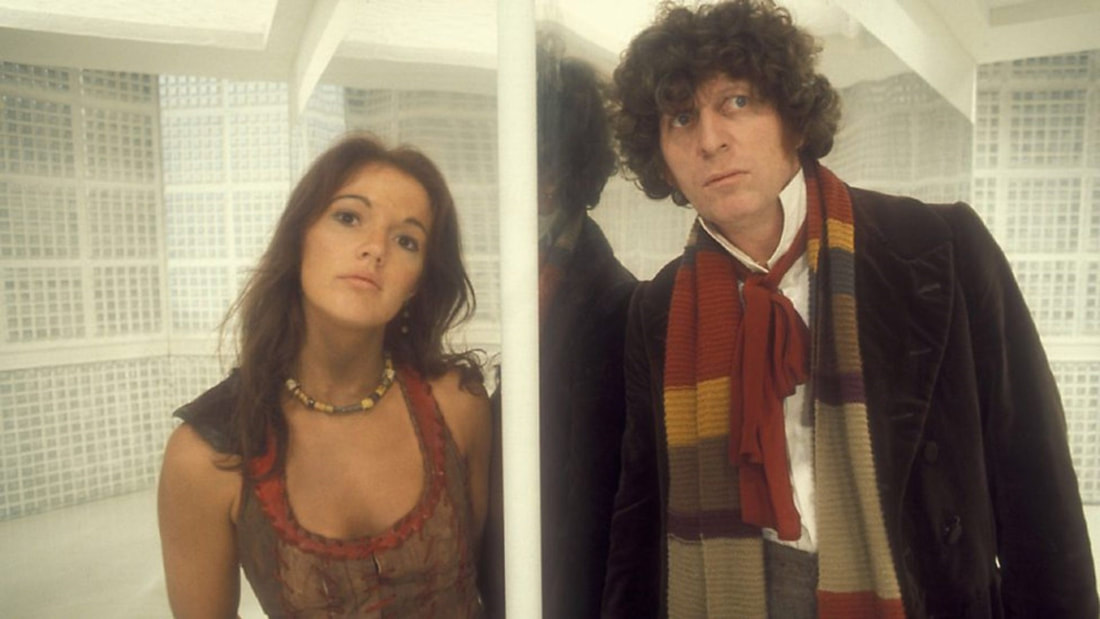

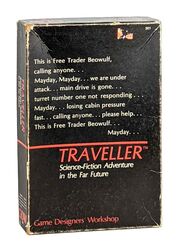

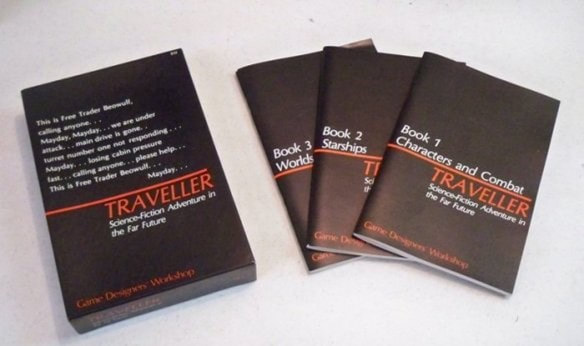

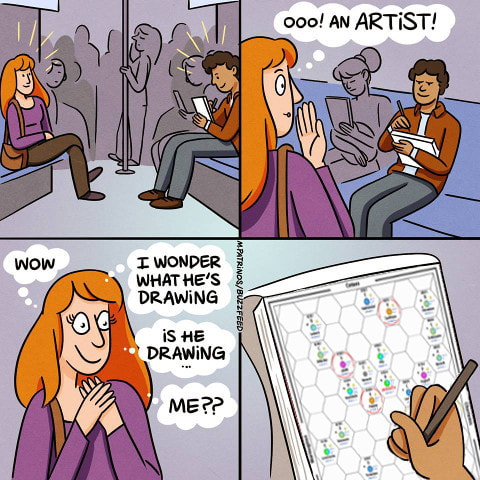

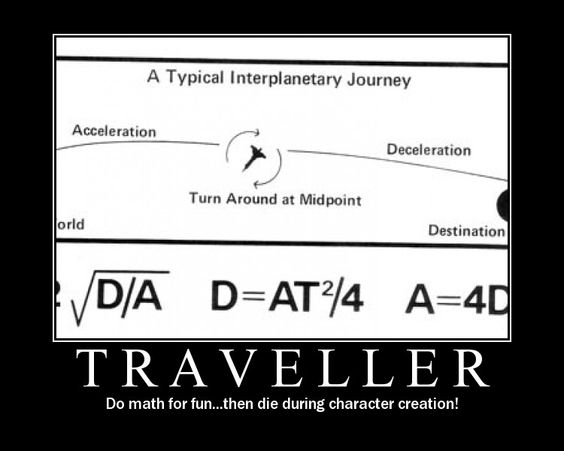

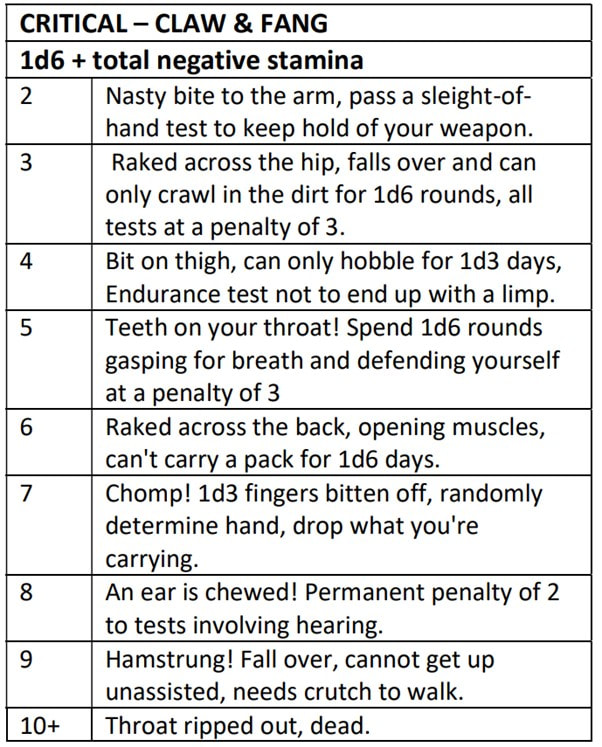

Before I talk about the Warpstar! RPG by Greg Saunders, I want to take a long route around. I'm a Star Wars kid. I was 10 when Star Wars premiered in the UK and went to see it on my 11th birthday. I was blown away. Obviously, I had to own the action miniatures, a cardboard Death Star, the board game, the comics and a collection of those strange cards you bought with bubblegum (which I detested). I'd been groomed for Star Wars by the UK comic 2000AD which had appeared earlier in 1977 and thrilled me with dinosaur hunting time-travellers, Dan Dare and, of course, Judge Dredd. The 2000AD Summer Special had heralded the arrival of Star Wars with a centre splash page that conveyed no idea of who the hero was or who the baddies were (Jawas, perhaps?) but the mysterious images pierced my soul with their distinctive blend of space romance. The 1977 2000AD Summer Special: the caption for Han Solo and Chewbacca reads 'Luke Skywalker takes a break with one of his friends.' After that, I loved Sci Fi. I'd loved Science Fiction before, of course. I adored Doctor Who and the Tomorrow People on TV and was an avid fan of Space 1999: the distinctive Eagle spaceships from that show were a treasure childhood toy along with an Interceptor from the earlier Gerry Anderson show, U.F.O.. Doctor Who acquired a, err, charming new companion in 1977, but Tomorrow People had the haunting and enigmatic opening sequence and a stranger and more provocative concept. Best. Toys. Ever. My first ever memory of watching TV is the episode of Star Trek where Kirk fights Spock with weird weapons in an arena: I was, I think, 3 or 4. Are you hearing the music in your head? But Star Wars involved a sort of commitment to glorious starscapes, roiling planetary surfaces, lasers in the darkness and gleaming battle armour. The odd thing is that, within a year of watching Star Wars for the first time, I was playing D&D. Roleplaying quickly dovetailed back into science fiction, with the Gamma World RPG and Traveller in its iconic black box. Age cannot wither her: there will probably never be a RPG set this ... beautiful Yet science fiction roleplaying just never captured my imagination. Gamma World was a lark with its gun-wielding mutant bunnies, but it just wasn't serious the way D&D could be. What about Traveller? Well, I certainly tried it. Who couldn't love the sleek modernism of the three-book box set, the cool black-and-red iconography, the tantalising mayday from Free Trader Beowulf ... Traveller: Science-Fiction Adventure in the Far Future was clearly a serious game set in a serious universe. I spent merry hours rolling up planets and populating my own sector maps. Yes, and not just sector maps, but rolling up animals and random encounter tables for those planets, then rolling up all sorts of retired Marines and cashiered Naval Officers ... Notoriously, the process of rolling up a Traveller character could result in dying during background history. Traveller invites you to create a 40- or 50-something PC who has already had a proper career in the military or in politics but then decides, in a ludicrous mid-life crisis, to go gallivanting round the universe getting into hare-brained scrapes with a bunch of strangers. As a roleplaying proposition, I found it a bit of a stretch back in my teens. Now that I'm the same age as those characters, it's no clearer to me what Traveller PCs think they're up to. So, I rarely played Traveller and when I did, the results were underwhelming. Traveller just never seemed to catch fire. There wasn't, for me, a story that was dying to be told and needing Traveller as its idiom. There was just a lot of aimless wandering in space ... heists ... bounties ... patrons in space bars ... the cost of repairing ships ... Twilight's Peak (1980) was a striking scenario but I just couldn't sell it to my players because, well, I wasn't sold on it myself despite Andy Slack's glowing review in White Dwarf #24 ('This is how Traveller should be. Buy it.'). Back to the dungeon I went and never really looked back at SF RPGs. (My) Problems with SF RoleplayingPart of it was just maturity. Traveller isn't as easy for teenagers to switch on to as D&D. In a fantasy RPG there are standard tropes: you arrive in a village, you go to the inn, some ageing peasant tells you of strange goings on at the ruined keep and the disappearance of the miller's daughter, off you go to clean the site out of kobolds and rescue the maiden. OK, you could substitute 'planet' for village and 'spaceport bar' for tavern and, I suppose, a 'disused orbital space station' and a 'missing corporate CEO' (female, if you insist). But immediately , questions intrude. What sort of planet? What sort of spaceport? What exactly is this orbital facility? Which corporation? Why isn't anyone else dealing with this? You might say that answering those questions is precisely what makes for designing a good adventure - and you'd be right. But my problems were closer to home. D&D offered easy access because everyone knows what a medieval village, tavern and ruined keep would be like - but everything needs thinking about in a SF RPG and nothing can be assumed. Or so it seemed to me at the time. In any event, Traveller seemed to set a high entry bar in terms of conceptualising and preparing the scenario, while not offering particularly clear hooks. You see, Traveller was basically the Nineteen Seventies In Space - and a rather banal, suburban take on the Seventies at that. Traveller didn't have laser swords, space wizards, godlike AIs or matter transport beams, let alone smart drugs, cyber-enhancement or netrunning. There was a sort of austerity to Traveller: computers were big box-y things, laser pistols were inferior to conventional slug-throwers in most contexts, the PCs were middle aged, psionics were rare, aliens scarce. When Traveller's official setting introduced the Aslan lion-people and Vargr dog-people, they were hardly compelling. Gentle reader, you might be tearing your hair out. Why didn't I just add those things in if I wanted them so badly? Of course, I could have. But I think I was as enthralled to Traveller's severe aesthetic as I was repelled by it. The game seemed to demand to be taken on its own high-minded terms. It would seem ... somehow, I know not how ... clumsy to foist lightsabres, transmat beams and cybermen onto Traveller. It would have been indelicate. Jejeune. I was too much a roleplaying snob to let myself have fun. Hey, Idiot: why not play Star Wars? A friend has reminded me that West End Games did a fantastic Star Wars RPG back in the '80s. I remember playing it, now that my memory is jogged. I owned the d20 Star Wars and Star Trek RPGs way back when as well. But ... I don't know. I've never really cared for tie-in games. I'm not bothered about the Dune, Blade Runner or Firefly RPGs either. Maybe it's my snobbery again, but I wanted a RPG that enabled me to create something like Star Wars or Firefly - without roleplaying in the official universe of those franchises. For whatever weird reason, I've been looking for a SF RPG that would make me want to create my own science fiction, not inhabit someone else's. OSR To The Rescue !My rehabilitation in SF RPG was a long time coming. I contrived to miss out on the genuinely up-to-date SF RPGs of the 1980s (Cyberpunk, SLA Industries) or the loony SF mash-ups of the '90s (Rifts, TORG). I somehow managed to avoid Star Frontiers, which offered actual D&D in space and would surely have disabused me of the hurtful notion that SF roleplaying had to be particularly clever or sophisticated. 'The Playable One' seemed like a direct dig at maths-heavy Traveller. There's a lovely retrospective of Star Frontiers but by 1980 I'd been scared off by Traveller and stuck to my fantasy furrow. I never really looked at SF RPGs again until quite recently, when the OSR trend for adapting original D&D led me first to White Box, then White Box spin-offs like Eldritch Tales (last post) then to James M Spahn's White Star. White Star comes as a perfectly-serviceable basic rules and an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink Galaxy Edition (which you might as well go for if you're getting the PDF since the digital versions cost the same). White Star is a beautifully-presented adaptation of White Box style D&D into a SF idiom. It is also completely shameless about porting in Star Knights with their laser swords, alien brutes, computer-hacking cyphers, cyborg, superheroes, mechas and a host of other stereotypes to create a broad palette you can pick and choose from. I really wish I'd found something like this in my '80s teens. If White Star has a problem, it's perhaps that it's too broad. With every science fiction and science fantasy trope on offer, it risks losing the idiosyncracy that intrigued me in Traveller: the offer to roleplay in a highly distinctive universe. With White Star, the problem isn't all the stuff you have to add in; it's the stuff you have to take out. Interlude: Lady Blackbird and Scum & VillainyDuring the first Lockdown there was an opportunity to roleplay with friends via Zoom and we tried out Lady Blackbird by Jon Harper: it's a free mini-RPG and you can find it here. We also played another of Harper's games, the excellent Blades In The Dark. Blades has a sister product called Scum & Villainy and I sourced a copy of that in my newfound enthusiasm for space romance. Lady Blackbird is a 15-page RPG with a set of pre-generated characters who start off as prisoners on board the imperial cruiser Hand of Sorrow. The rag-tag group have to escape and get back to their ship, the Owl. The group includes a space princess fleeing an arranged marriage, her bodyguard, a romantic space captain and his quirky crew. The universe is the 'Wild Blue' (shattered worlds around a dimming star), with breathable space, space squids, space goblins, space magic. It plays out like a Saturday morning matinee. It's steampunk Star Wars. It's great. Blades in the Dark is a bigger project, but Scum & Villainy grounds its wide-open RPG system in a manageable small corner of space called the Procyon Sector: four out-of-the-way solar systems linked by interstellar gates but somewhat cut off from the vast galactic empire. Here's a setting with space mystics, alien AIs, sci-fi religions, glamorous guilds of space-thieves, very much space fantasy. So, Star Wars again (as the title alludes). John Harper has certainly won me back to SF RPGs, but of a distinctive genre: space romance. His trick is to set the action in a very localised part of a very particular sort of SF universe: one with a lot of the accoutrements of fantasy roleplaying. The catch is, you really need 5 players to run Lady Blackbird (and it's a one-shot); Scum & Villainy is designed for campaign play, but it's quite demanding. Warpstar To The Rescue (and about time too!)Recently I came across Greg Saunders' fantasy RPG Warlock! (reviewed here) and was impressed by its artfully minimalist rules and striking tone. I quickly discovered that Warlock! has a sister product: SF RPG Warpstar! (see what they did there? both games begin with war-! and end with -!). Could this be the game that properly lures me back to SF? Warpstar! is very much Warlock! re-skinned for SF. You have just two stats (Stamina and Luck) and a set of 32 skills you add to a d20 roll, trying to hit 20+ or just beat your opponent. These skills start at 4, 5 or 6 but five of them are career-specific and you have 10 extra points to split between them, to a maximum of 10 or 12. Some are generic skills (spot, Stealth), some familiar from the fantasy game (Short Blade, sleight of Hand) and some are new to the SF setting (Astronav, Ship's Gunner, Zero-G, etc). One, Warp Focus, lets you do 'magic.' The 24 careers cover the spectrum of SF tropes. Some are professions (Bounty Hunter, Diplomat and I suppose Pirate and Gambler) but others are more like archetypes (Street Kid, Rebel) and one, Warp-Touched, is a space wizard. As well as boosted skills, each career comes with a couple of tables to roll (or choose) your background and quirky details of your motivations, past escapades, enemies made and reputation earned. As with Warlock!, there is a ton of imagination in these tables, which accomplish more world-building than an entire chapter of setting, and a slightly seedy tone that Greg Saunders delights in. Characters can use experience to switch careers, broadening their repertoires, and gain access to Advanced Careers if they want to push their skills into the teens. In a variation on the Warlock! template, everybody starts with a randomly-rolled Talent, to give PCs a little more heroic oompf than the down-at-heel misfits of Warlock! ever enjoyed. Combat is a standard skill test, but hand-to-hand combat involves an opposed roll, trying to roll higher than your opponent. The risk of launching an attack but coming away as the one who takes the damage should make players cautious about resorting to violence. Once Stamina hits zero, you roll for lasting Criticals, the worst of which kill you outright. With PCs boasting Stamina scores in the teens or low 20s and weapons doing damage ranging from a d6 (knives, etc) to 2d6+4 (pulse guns), you can afford to get hit once. but after that you consider retreating, which carries no penalty. The intention is that combat usually goes to first blood, then NPCs (and wise PCs) back off and try a different approach. Stamina is regained rapidly - you get half of it back after a brief rest, all of it after a long rest. Magic enters the game because of the Warp Space that ships use to cross interstellar distances. This isn't the clean and clinical hyperspace of Star Wars; no, it's the chaos-realm of Warhammer 40K and anyone exposed to it risks being mutated, but one such mutation is the acquisition of spell-like powers called Glyphs. As with Warlock!, spells/glyphs are physical things that an aspiring magus has to hunt down, bargain for or steal from other practitioners. The main addition to the game is the addition of space ships and ship combat. It's assumed each PC group gets their own space ship and you can roll or choose from a set of 6, each with a distinctive design and aesthetic: from the elegant D'Aubigny Envoy Cruiser to the tough, fast but unfashionable Kilos Star Hauler. Spaceship combat is handled just like personal combat. Ships have Stamina (called Structure), armour, built-in weapons that deal damage in a similar range to (but great scale than) personal weapons. It's a clean, intuitive system that once again encourages brief skirmishes then running away once someone takes damage. The setting is a vast Galactic Empire known as the Chorus. This is ruled by fractious noble houses who, in a clear nod to Dune, achieve an almost-immortality through using the space-drug Cadence, the source of which is known only to the supreme Autarch. Other factions include the military Hegemony, the unscrupulous Merchant Combine and the arcane Warp Consortium whose possession of weird technology makes them, in effect, a guild of sorcerers. A bestiary includes some oddball aliens, some of which (the Fruiting Dead and Borg-alike Nodes) imply cosmic horror, but many of which seem to delight in upsetting expectations, such as the troll-like Jondo who are actually placid and philosophical or the hideous dog-monster Borrs who are actually deeply cultured. Warp Entities allow for the inclusion of space dragons, space vampires and space demon-gods, according to taste. So, is it any good? Yes. Warpstar! is quick, clean and intuitive - as you'd expect from an adaptation of an already-solid game like Warlock!. The setting is highly serviceable while being vague enough to customise. The character careers offer lots of hints for your first few scenarios. Nobody dies in character generation. Some features are 'baked in' to the rules. There's space-magic, for example. You could prise it out, I suppose, or recast it as psionics if you are allergic to fantasy in your SF (although references to Warp mutations run all through the rules and setting). The combat system, as noted, does tend to impose a cautious, scaredy-bully style of play, where antagonists shoot or stab each other once, then down their weapons and negotiate. The skill system means that PCs tend to succeed between a third to half the time, which is a bit low for a truly swashbuckling game, a bit high for gritty techno-realism. But I like these baked-in features. They give the game some character that seemed to be missing in White Star, for example. I could see myself using Warpstar! to scratch the itch for SF one-shots - or to adapt Traveller scenarios (such as used to feature in White Dwarf of old) into a slightly more space operatic idiom. I've also acquired the Omoron sourcebook, which is a Warpstar! detailed setting: a peculiar star cluster that's a bit like the Procyon Sector in Scum & Villainy. It features a couple of scenarios, but I'll not mention them until I've run them on my gaming group. Omoron (and several other sourcebooks for Warpstar!) is available from drivethrurpg The only criticism I can make of Warpstar! is the price. The rules are available as PDF and hardback. The PDF is £9 which isn't exactly cheap, but you're getting a solid game and a lot of setting ideas for your money. The hardback is a stonking £33. Why so expensive? Well, it's because this is the premium colour price point. Is there a lot of colour in the rules? No, barely any - but Greg Saunders explains "the premium colour option has been chosen for the print version as it represents a much better quality of paper with an improved look and feel." I bit the bullet and invested in a physical edition because I find it hard to use PDF rules sets in play; I can attest that the paper is very good quality, the book looks clean and clear and, well, very SF, so that's a big tick for Artistic Standards. But it has to be said the book really doesn't need this treatment, especially as the art style throughout aims for the same scuzzy 1980s-fanzine vibe that informed Warlock! I mean, it looks great, but it would marry very nicely with coarser paper and lower resolution. You can't help wishing there was a nice cheap non-premium edition, or even better a non-premium softback. If you could buy a physical copy of Warpstar! for, say, £10-15, I'd cheerfully treat my group to 'players copies' to build commitment and speed up character creation. Warpstar! hits my sweet spot. It delivers space romance (which I think is my preferred genre, rather than Hard SF) with a simple but distinctive rules set. It's got theme and imagination running through it. It posits player characters who are quirky and distinctive, but of less-than-heroic stature. It will hit the gaming table a few times over the next few months. I'll review the Omoron campaign book when it does.

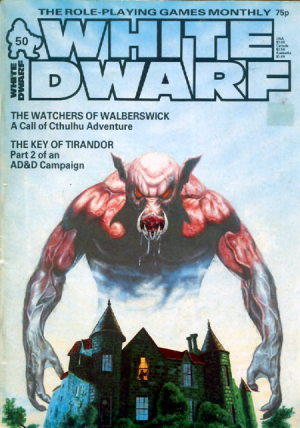

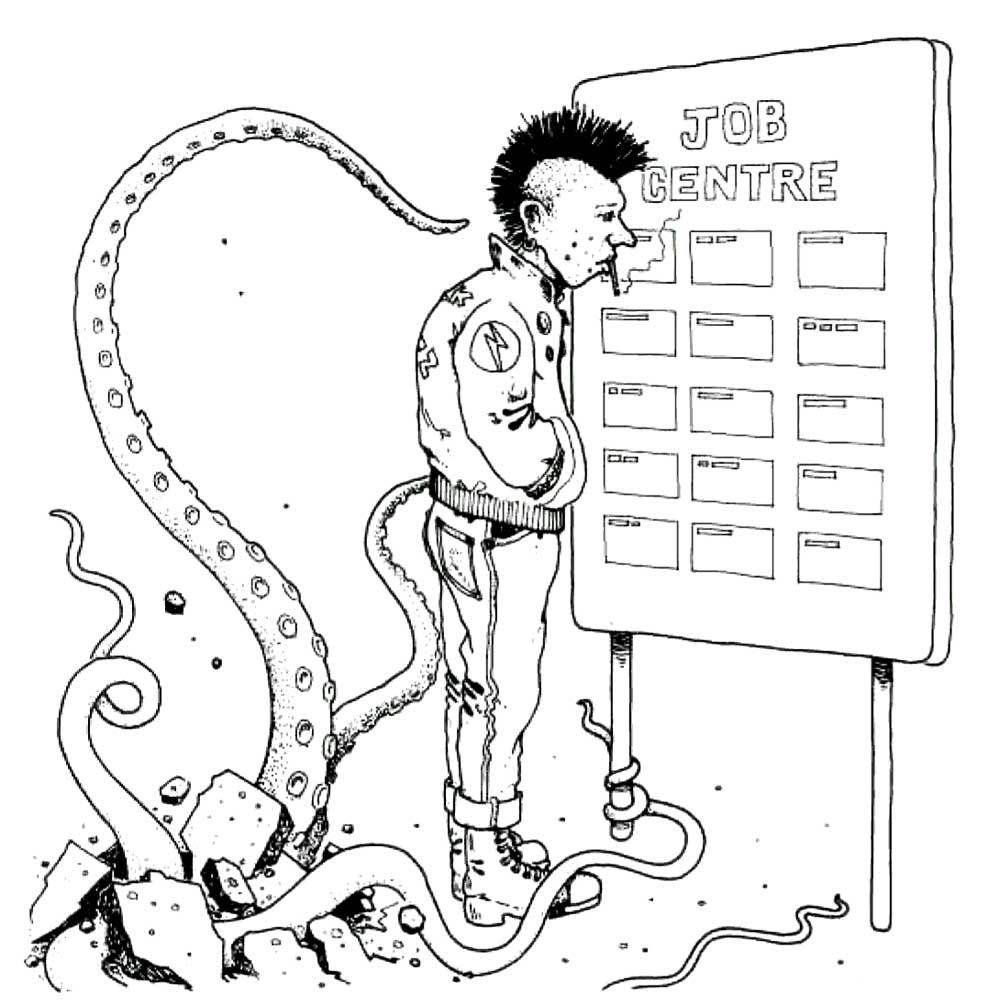

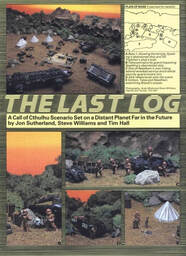

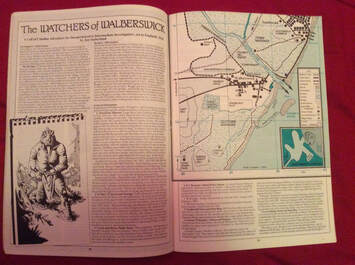

Back in the early-1980s, White Dwarf became the premier magazine for the roleplaying hobby. In America, Dragon reigned supreme in its support for D&D, but White Dwarf covered the whole hobby (more or less) and was unequalled for the quality of its journalism and contributions. There really were some fantastic scenarios for D&D and Runequest in particular, a brilliant column by Andy Slack supporting Traveller, a bestiary feature that inspired most of the AD&D Fiend Folio and great articles on campaign design generally. My favourite issue of White Dwarf (24) and the Fiend Folio, a sequel to the AD&D Monster Manual containing a mixture of monsters from TSR modules and the pages of White Dwarf. All things must come to an end and as White Dwarf moved into its 50s (in 1984) there was a perceptible dip in the imaginative temperature. Don't get me wrong: there were still some cracking scenarios to be published and most issues had a solid article or two, but it stopped being groundbreaking. The RPG companies were getting into gear supporting their own products with increasingly thoughtful modules and campaign settings. There was just less for a magazine like White Dwarf to do. Perhaps also, less consensus in the hobby over who it was primarily for. Ultimately, White Dwarf would turn into a showcase for Games Workshop's own products, but that was still a few years down the line. There was life in the old dog yet. One promising sign of continuing relevancy was a trend for scenarios for a new RPG: Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu, now a mighty industry behemoth but then a quirky outlier in the gaming constellation, pitching a roleplaying experience of dread, futility and, ultimately, madness and death in the world of H P Lovecraft's distinctive American Gothic. Call Of Cthulhu had been reviewed back in White Dwarf 32 (1982), with reviewer Ian Bailey clearly as impressed by the game as he was perplexed by how to make use of it (a common response at the time). He also observed that the game was "U.S. orientated and consequently any Keeper ... who wants to set his game in the UK will have a lot of research to do." The original Call Of Cthulhu RPG (the best cover too) and the White Dwarf issue that reviewed it - along with an excerpt from Ian Bailey's review Of course, since this was the Golden Age Of White Dwarf, it only took 10 issues for hobby maestro Marcus L Rowland to appear in the magazine, offering 'Cthulhu Now! - Call of Cthulhu in the 1980s.' The article grounds itself in an early '80s setting with an illustration of a punk studying a Job Centre noticeboard while a tentacled gribbly writhes up behind him! A follow-on article offered three contemporary scenarios: Dial 'H' for Horror, Trail of the Loathsome Slime, and Cthulhu Now! This opened the floodgates for White Dwarf contributors to submit a range of Call of Cthulhu material, including Cthulhu in space (The Last Log, by Jon Sutherland, Steve Williams and Tim Hall, from issue 56 in 1984) as well as Cthulhu in rural 1930s England (The Watchers of Walberswick by Jon Sutherland, from issue 50 in 1984) and Cthulhu in British Mandate Palestine (The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah by Steve Williams and Jon Sutherland, from issue 60 in 1984) . You'll notice Sutherland's name recurring? He was quite prolific in 1984! These early scenarios are typical for White Dwarf: they are concise but erudite, with a close attention to period and setting; they are thoughtful affairs, far removed from the pulpy excesses of Chaosium's own globetrotting campaign packs (like the epic Masks of Nyarlathotep, also from 1984 and closer in tone to a Bond movie than a Lovecraft story - a really good Bond movie spliced with Indiana Jones but pretty far from Lovecraft's cerebral interests). I suppose Jon Sutherland's efforts were attempts to take Call Of Cthulhu by the horns and deliver a narrative experience that feels like it really could be a horror short story by Lovecraft himself: very low-key but also, whatever their ostensible setting, very British. All this preamble is the context for me blowing the dust off White Dwarf #60 to run Sutherland's The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah on a group of three players over two evening sessions. Why pick this scenario? Well, it was used as the final scenario in the 1984 Games Day official Call of Cthulhu Competition and the introduction boasts that it provides "an interesting one-off session or addition to an existing campaign" - which sounds ideal for my needs. Next, the question of which rules set to use? That might sound odd, but post-CoC rules have proliferated recently and my respect for Sandy Peterson's imaginative achievement with Call of Cthulhu is only matched by my distaste for CoC's rules themselves, which are Chaosium's Basic Roleplaying system, with the addition of a diminishing Sanity (SAN) stat that spirals down to nothing as the Elder Nasties emerge. Lots of skills expressed as percentages, professions defined by skills and a lumbering combat system that manages to simultaneously make player characters too flimsy (any Mythos monster will squish them) and too tough (you have to shoot or stab someone several times before they fall down). The two contenders to replace CoC are Paul Baldowski's The Cthulhu Hack and Joseph D Salvador's Eldritch Tales. You can find both on drivethrurpg, but Cthulhu Hack is also available from the nice people at Zatu I've written about Baldowski's Cthulhu Hack before and, like most Hack games, it's great for pick-up-and-play. There are only two problems. One is that it tends more towards the pulpy action-adventure side of the CoC congregation and the other thing is that its Hack-derived mechanics don't greatly resemble classic CoC at all; both are problems for adapting the reserved tone and low-key assumptions of Sutherland's CoC scenarios. No, Salvador's game is the one I choose for this. For those who don't know it, it bills itself as Lovecraftian White Box Roleplaying. This means it takes the bare rules and conventions of Original D&D, especially the iteration known as White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game by Charlie Mason. Now, I fell in love with White Box when I attempted a long D&D-style campaign during 2020's Lockdown, so I'm excited by this. Mason's White Box is free (FREE!) on drivethruprg but a physical copy is stupidly cheap on Amazon too Eldritch Tales is a beautifully presented indie RPG product with evocative (and pleasingly amateur-style) art, fantastic layout, a delightful overview of the Lovecraftian milieu and careful explication of the (essentially simple) rules. Only the presence of a much-needed index would complete my bliss! The game invites you to create characters by rolling 3d6 for the classic six characteristics (Strength, Dexterity, Wisdom, etc.). Non-combat 'Feats' are attempted by rolling a d6 and you succeed on a 6 if your relevant characteristic is low (6 or less), on a 5-6 with ordinary characteristics and on a 4-6 of your relevant characteristic is 15+. Having a particular skill either adds +1 or +2 to the roll or lets you roll twice, choosing the best score - or sometimes both. So much better than faffing around with percentage dice. There are four character classes: Antiquarians, Combatants, Opportunists and Socialites. Within your broad class, you also roll or choose an Occupation that might give you particular skills, funds or possessions. Your Character Class gives you a d6 Hit points at first level (d6+1 for those hardy Combatants). Most weapons do a d6 damage (d6-1 for a thrown knife, d6+2 for a shotgun). Yes, every exchange of violence is potentially life-ending, especially as going up a level usually adds just +1 to your Hit Points. The levels only go up to 6th by the way. I think if your investigator gets to 6th level (with usually 3d6+1 HP), you should interpret that as the universe telling you not to push your luck any further. Insanity is a score that goes up during nerve-wracking encounters. If it ever gets to the level of half your Wisdom you gain a permanent insanity and if it ever matches your Wisdom you become a gibbering NPC. There are short-term shocks for people who fumble their Insanity saving throws (roughly 10% of the time) or gain 3 Insanity in one go (not that uncommon either once gibbous entities come calling). Two nice features of Eldritch Tales are the tables to roll up your Contacts (you have quite a few of these) and the table to roll up your Character Relationships. There are 20 of these suggestions, ranging from 'You are in love with another character (or their spouse or sibling)' through to 'You and another character witnessed something astounding.' These are so helpful for turning a bunch of numbers on paper into a team of investigators ready to risk life and sanity to investigate eldritch mysteries together. Past that point, Eldritch Tales is old-skool D&D: you roll saving throws and roll to hit Armour Class, there are familiar spells and monsters from the Mythos, you gain experience points from defeating the monsters or solving mysteries, you go up levels. The Bleeding Stone of Iphtah by Jon SutherlandThe scenario kicks off in Jerusalem in the 1920s, a time when the Palestine Mandate was overseen by the British Empire. It's a fantastic setting to launch any story - so good in fact that Kenneth Branagh (clearly also a fan of '80s White Dwarf) stole the idea to begin his recent film of Murder On The Orient Express. The PCs are Percy Goodfeather, a Gentleman Socialite who is searching for his vanished sister Darcy. He brings with him his university friend Howard Harris, an Australian Occultist Antiquarian: the two bonded when another friend disappeared, never to be seen again, during one of Howie's rituals in the college rooms. Percy's largesse helps fund Howie's growing drug addiction. They have been brought to Palestine by Joe Birdwell, an Opportunist Outdoorsman who knows the region and its peoples. Birdwell is secretly in love with Darcy Goodfeather, but he knew her as Dahlila de Gul, a torch singer and medium; he was an enthusiastic participant in her demimonde orgies until her strange disappearance. He has tracked her to Jerusalem, but not told Percy of his sister's double life. What's Going On? Actually, none of this is in Sutherland's scenario; these are incidents derived from Eldritch Tales' table of relationships and a few Tarot card draws to help brainstorm a plot. But I can tie it together

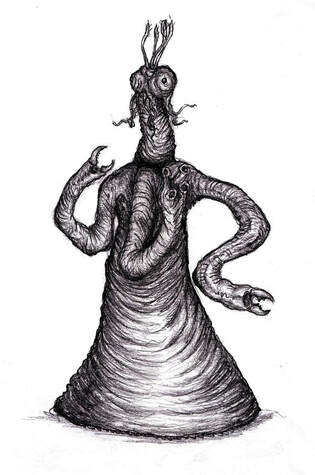

Start With Action The scenario starts with the PCs browsing a museum in Jerusalem when they are approached by a shifty Turkish gentleman named Lakey who wants them to take on a job for his boss, a businessman named Lotto who owns the Domino Club and is obsessed with antiquities. This is a run-of-the-mill CoC plot hook and the two NPCs are a delightful hommage to Peter Lorre's Ugarte and Sydney Greenstreet's Ferrari from Casablanca (1942). The sweaty grifter and the intimidating black marketeer Except that being led by the hand by a bunch of NPCs to a patron who explains why they have to go to a dig site in the Judean Mountains and chivvy along an archaeologist called Foster who has promised to bring back treasures for Lotto but has so far turned up nothing ... well, that's a slow start my friends. So instead we have Joe Birdwell see Darcy pass by in the street - and he jumps out of the window to give chase. Darcy is being stalked by dangerous looking Bedouins but when Joe reaches her she reacts without recognition. One of the Bedouins fires a gun at Darcy, but Joe is hit and Darcy takes off in a car while the street erupts in confusion. Percy and Howie arrive to find an Arab doctor treating Joe and warning them that the Bedouins were tribesmen or a cult called Pachalim (made up name but it'll fly) and very dangerous customers. A Side Plot Develops The PCs are supposed to take the job from Lotto and journey to the dig site at Iphtah, but my ad libbed side plot has taken over the story. Joe goes to find out more about the Pachalim from a contact - an Arab businesswoman nicknamed 'the Ibis' (for her pronounced nose). This vociferous widow with her melodramatic flights of insulting rhetoric quickly becomes one of my most beloved NPCs! Joe parries and feints and handles her beautifully and ends up shadowing a pair of Pachalim goons as they invade the seedy guest house where Darcy is staying. Joe gets knocked out when he tries to intervene but, waking as a prisoner of the Pachalim, learns that they are trying to stop 'the Forgotten' (almansiayn) from carrying out a ritual. Yup, they're the good guys. Joe is released, doped up with hashish, and stumbles home to the Domino Club. Percy and Howie have been pulling their own contacts, find out a lot about Foster and discover that the local gangs that Lakey buys drugs from have acquired new weapons in the form of Rot spells that do horrific things to their victims. When the three PCs visit Darcy's guesthouse the next morning, they find Darcy has moved on, but one of the Pachalim is there, dead from a Rot spell, and clues point to Iphtah where Prof. Foster is digging. Yes, this is me trying to re-direct things because this side plot has taken up the evening and we haven't even arrived at the location of the actual scenario. Journey To Iphtah The main scenario takes place at the dig site at Iphtah, where Prof. Foster is going mad. The Professor is using opium to keep the Yithians out of his head, but he's run out of drugs and thinks that Lakey (his supplier) is holding out on him. The PCs get to snoop around the site, spy on the erratic Foster and realise strange things are afoot, but this is a programmed scenario where the PCs have to be onlookers to certain events and no amount of roleplaying or researching will speed them up. In the middle of the night, Foster murders Lakey to get at the drugs, then overdoses himself. The PCs manage to stop the truck escaping with Lakey's corpse by shooting out a tyre. They are left at the dig site with no Lakey, no Professor but a mysterious red stone - the Bleeding Stone of Iphtah. This is where it gets creepy, because a bunch of Dimensional Shamblers show up if anyone tries to remove the Stone from the site without performing the ritual. I hide the Shambles in an eerie dust cloud (for extra creeps) and use them as silent sentinels who murder the Arab labourers to establish their monster bona fides but otherwise leave the PCs to explore. There's a buried shrine to be found and opened and the Stone has to be 'bled' inside a pit to power up the ritual and then ... err .. and then ... ah, well, that's about it really. The PCs are free to leave. Perhaps suspecting that things could turn out rather anticlimactic, Jon Sutherland suggests a raid by snooping Bedouins and I've already set up the Pachalim for exactly this sort of work. The PCs end up stuck in the shrine with the Pachalim outside with rifles in a tense standoff. Then Howie the Antipodean Antiquarian leads the charge, shoots the Pachalim sheikh dead, but is riddled with bullets himself. Percy and Joe shoot their way to safety and the Shamblers disembowel the fleeing Pachalim. Percy and Joe get to leave the site, supervised by the silent Shamblers. And that's, kind of, where it ends. The scenario doesn't make it clear just how the ending is supposed to go down. My players decide to return the Stone to Lotto and continue their pursuit of Darcy. They are unaware of the role they have played in facilitating the arrival of the Yithians by performing the ritual. Evaluating the Scenario and Eldritch TalesThe Bleeding Stone of Iphtah is a rather slight affair. In fact, all of Jon Sutherland's 1984 scenarios are oddly muted. I think they were written in deliberate contrast to the gangbusters style of American CoC material, to be atmospheric, unsettling and cryptic, rather than kinetic, deadly and cosmic in scope. In all of them, the Mythos is a marginal force, largely operating off stage. The PCs spend most of their time exploring a realistic but evocative location, then at the very end there's a Mythos intrusion. The central problem is that there's no way for the PCs to understand the significance of what's been going on or their role in it. Now, in an ongoing campaign this is acceptable - further down the line, the PCs might uncover information which casts a revelatory light on the goings-on at Iphtah and realise that, by performing the ritual, they brought the Yithian-apocalypse a dread step closer. They might then understand why Foster was taking drugs and why the Shamblers appeared to stop them leaving with an un-bled Stone. But as things stand, there's no way to learn any of this - and this was a scenario, you will recall, billed as "an interesting one-off session or addition to an existing campaign." One wonders what the contestants at Games Day '84 made of it. I know some people will retort that Lovecraftian roleplaying is supposed to be mysterious and it's a good thing, not a bad thing, if a scenario leaves players puzzled and disquieted. Yes, that's true, I suppose, but my taste is more for a scenario that places the players in positions of at least partial knowledge. Too much of Iphtah was meaningful only for the GM, even with my improvisations. But these are minor gripes and I should perhaps essay another Sutherland scenario - perhaps the well-received Watchers At Walberswick - before forming a judgement on his output. Eldritch Tales served us very well and is now my go-to RPG rules set for Coc material. I was pretty generous in handing out experience points for roleplaying (and why not? the roleplaying was stellar!) and of the two characters who survived, Percy reached second level (losing some Insanity and gaining that precious extra Hit Point) with Joe just missing his level-up. I'd love to dust off a larger campaign pack - perhaps Shadows of Yog-Sothoth - to run using Eldritch Tales. However, I became very aware of how flimsy Eldritch Tales PCs are compared to CoC: every gunshot or knife wound is potentially lethal. Perhaps swashbuckling Cthulhu Hack would be a better fit for those pulp-y Chaosium campaigns? But for the studious and low-key Call Of Cthulhu scenarios that White Dwarf and Jon Sutherland were publishing in the mid-1980s, Eldritch Tales is ideal.