|

Guess who's back? Back again - on drivethrurpg or on Amazon Back in 2020, The Ghost Hack was the first of my ventures into indie RPG publishing inspired by The Black Hack's irresistible mechanic of old school D&D stats married to a shrinking usage die. It was a bit primitive but it sold nicely - a Silver Best Seller in drivethrurpg. I was obsessing over ghost stories at that time and followed The Ghost Hack up with a slightly more polished expansion and a couple of short scenarios. Now I've released a revised edition that incorporates both books in one volume, adds a bunch more content, and brings the rules into harmony with the more polished version I ended up using for The Magus Hack. Before I talk about the new Ghost Hack, I need to say something about its source material. Wraith and Why It Never Rocked MeBack in the '90s, waiting for the next chapter of White Wolf's World of Darkness game line to see print occupied the space in my life that was later occupied by waiting for Game of Thrones to release a new season. 1991 brought out Vampire: The Masquerade and then Werewolf: The Apocalypse in 1992 and Mage: The Ascension in 1993. By 1994, I was a frothing fan and the arrival of Wraith: The Oblivion was a bombshell, with its fantastic cover of interlinked chains, moody spectral art and surreal, grotesque setting of the rotting Shadowlands and hyper-real Tempest, with slave-harvesting wraiths and Oblivion-worshipping Spectres. Mind. Blown And yet. And yet. Wraith remains the one World of Darkness game that has never worked for me. I've run long campaigns with the other main games but every attempt to launch Wraith has met with, well, dissatisfaction. The closest I came to making Wraith fly was a version set in the 18th century Caribbean. Pirate Wraiths are cool. Part of the problem is Wraith's setting which always struck me as incompletely realised. The other World of Darkness games are set in a bleak dystopian version of our world. Although werewolves and mages can step away into fantastical spirit worlds, they are still products of this world. Wraith is weird. Where are you? A sort of parallel reality called the Shadowlands that both is, and yet is not, the same as the world the living inhabit. The moment you start playing Wraith, you butt up against confusions about what everything looks like. Wraiths perceive the world through a filter of decay. But how does that work? Do buildings in the Shadowlands have doors and windows, or are they shattered and broken? Can wraiths read newspapers and watch TV - or is the paper rotten and the screen cracked for them? Wraiths get discorporated by rough contact with 'real' things. This makes crossing a street or moving through a house rather difficult. Wraiths are perpetually being bashed into insubstantiality every time someone opens a door into them, drives through them, kicks a ball at them. Your immortal vampire can walk down a crowded street at midnight, but your lordly wraith, weirdly, cannot. So where do Wraiths live? What do they do? Wraiths are supposed to be driven by obsessive Passions and tied to Tethers, which are objects or people that mattered to them. Yet they are also supposed to be servile minions in the Hierarchy, a Kafka-esque slave state of the dead. The rules invite us to imagine NPC wraiths who are clerks or legionaries in this vast bureaucracy of the afterlife. I get it: I've seen Beetlejuice. Yet these wraiths are also passionately tied to weird causes, like growing perfect tulips or avenging their wife's murder or finishing their unpublished novel. Where do they find the time? How can they be a committed servant of the Hierarchy and yet also dedicated to tracking down their cousin who disappeared in the Appalachians? There doesn't seem to be a way to combine both ideas of what a wraith is. Then there's the Shadow, which is your dark-side given voice, whispering in your mind and offering power in exchange for the gratification of its own Dark Passions. If every Wraith NPC has this sort of Jekyll-and-Hyde persona, the social world of wraiths becomes unimaginably weird. How does the Hierarchy even function if all wraiths are self-sabotaging all the time? The game recommends players roleplay each other's Shadows, acting as tempters and tormentors to one another. Great on paper, but I've never been able to get it to work. Some players are too amiable to play the Shadow with gusto; others throw themselves into it with such cackling enthusiasm that it derails the plot. Never mind that, you can't kill wraiths - at least, not reliably. A dead wraith tumbles into a hyperspace realm called the Labyrinth where it is tormented by its dark side. This psychodrama element tells you a lot about the highfalutin' play style going on at White Wolf head office, but for a lot of ordinary roleplayers it feels incredibly self-indulgent. Then the wraith reforms and it's business as usual. Yes, there's a limit to how many times you can do this, but the bottom line is that you can't kill a NPC wraith because they just come back again, chastened and more sorrowful. All of these conundrums weigh down a game that was already way too fiddly. Wraiths have Passions and Tethers, but also Dark Passions and Shadow Thorns, and Memoriam, and Angst; they are loyal to a Faction and a Legion as well as a Guild plus their own mortal attachments, as well as ... look, there's a lot to keep track of, a lot of dice to roll, a lot of points to tot up. So Let's Hack ItDavid Black's Black Hack is a short and sweet creative step away from Old School D&D. There are the familiar 6 Stats (STR, DEX, CON, INT, WIS, CHA, the old gang), plus character classes and levels. You roll a d20 to do stuff and you're trying to roll under your Stat. Penalties add to your die roll, making that more difficult. For example, attacking or dodging someone with more HIt Dice than you is hard: you add the difference to your d20 roll. Black's system lends itself very well to cheap and cheerful dungeon crawls - and in this regard I'm particularly fond of Michael Thomas's Bluehack, which condenses the already-concise Holmes Basic D&D rules into Black's ultra-simplified template. All on drivethrurpg for pennies - click on the image to hit the link The secret ingredient Black introduces is the concept of a Usage Die. This is a die you roll that gets smaller every time it rolls a 1 or a 2. It might start off as a d8, so if you roll it there are six chances nothing happens, and two that it shrinks to a d6. Once the d4 shrinks then PFFFT! the Usage Die has gone. In his original rules, Black only uses this mechanic as a way of tracking how many arrows you've got left or how much oil is in your lantern: don't bother keeping track, just roll the Usage Die every now and then to see if it's running out. Then I came across Matthew Skaill's The Blood Hack. Skaill's little book has two fantastic innovations. One is to treat a vampire character's blood reservoir as a usage die. Every time you use your blood to heal or activate a magical power, roll the die. Once the die has gone, you're a hungry vampire. The other is to make your vampire's Morality a usage die, so every time you do something evil you have to roll. But - and this is the clever bit - every time that usage die rolls a 1 or a 2, it doesn't get smaller: it gets bigger! A vampire with d6 Morality is pretty normal, a d8 Morality is a bit of a sonofabitch, a d10 is a sociopath, a d12 is a monster. If you reach d20 you are demonically horrible and if a d20 Morality Die gets any bigger then BOOM - you've turned into a NPC villain. This is a great push-your-luck mechanic. Sure, with a d6 Morality, the first time you murder someone there's a 33% chance your die is going to expand to a d8. As it gets bigger, the chance of further escalation shrinks, but the consequences get worse. There's only a 1 in 5 chance your d10 Morality Die will get bigger, but if it does, then watch out! What About the Setting?The Ghost Hack uses character classes over up to 10 levels of experience. These classes (or Trades) do the job of the Guilds in Wraith, giving you powers you can do for free and perks towards advancing in certain ways. As a Poltergeist, you can interact with objects in the Living World, and you'll probably get a high STR stat really fast. Levels and Hit Points don't feel weird or implausible in a ghost setting anyway, because of course your Hit Points don't represent your body: you don't have a body. The five basic character classes draw from common haunting tropes:

The core rules are agnostic about whether these classes are just abstractions for ghosts with different aptitudes or actual organisations. In the appendices there are rules for treating them more like guilds that instruct ghosts in their signature powers and guard their privileges jealously. Similarly, the rules offer a distant city of the dead called Dis (but you can call it Stygia), but leave it up to you whether this empire of the dead is just a rumour, a looming threat, or an oppressive reality. These ghosts can walk through physical objects freely - but they are hurt by iron and repelled by salt, so the physical world has its obstacles. The ghostly Afterlife takes place in our world, but for ghosts the sun is permanently eclipsed and the moon has a lurid tint, so the lighting is eerie. I offer five ghostly sects that can be allies or antagonists in your campaign. The Misericordium fulfils the role of the ghostly bureaucracy, but it makes more sense because, by recruiting clerks to write up the lives in its ghostly books, it steals away their memory of who they were. The other cults likewise replace your humanity with a Gnosis Die, so by joining them you surrender your soul, but escape from the burdens of conscience and attachment to the living.

Simplicity is the key feature of Hack RPGs. Half a dozen tables at the back of the book let you roll up NPCs with classes, powers, and spells, and plenty of tables throughout the book generate random possessions and encounters. There's a final appendix that lets you generate random scenarios and five worked examples that show how a feud between ghosts and vampires can take a very strange direction once the Church of St Thomas gets involved. One thing I've retained from the original is the fantastic pulp-style art from the NUELOW Stock Art Collection. The quirky, anachronistic, yet often deeply unsettling artwork is great for a setting where lots of ghosts still look and act like people from earlier eras. Copyright is @2024 Steve Miller, All Rights Reserved. The Ghost Hack is an approach to ghostly RPG - and Wraith, its template - that emphasises light-hearted adventure over personal horror. There's still personal horror there. Ghost PCs are slowly disintegrating and the end state is becoming a demonic Wight. You draw energy from your 'Mortal Coil' which means the people and things you cared about, and this can damage them. If you temporarily turn into a Wight, you are compelled to visit violence on your Mortal Coil. All these elements are horror tropes. On the other hand, there isn't a tyrannical and oppressive empire ruling the underworld, the slave economy has been marginalised and applies only to mindless 'Echoes' rather than true ghosts, the Shadow has been removed, as well as the psychodrama brought on by being defeated. These elements are reinstated in the Appendices, if you want morality dramas, player-vs-player psychodrama, underworld politics, it's all there for you. But the core rules focus a bit more on exploration, adventure, and facing peril. One change from the Wraith template is to do away with the destructive storms raging in the Underworld and replace them with 'the Dread.' This is an acidic fog that rises from Hades and smothers the region. Tocsins blare warnings and ghosts flee to protected Fanes. This phenomenon gets rather more consideration in Ghost Hack than did maelstroms in Wraith, but again: this fits with a game setting where the main danger is external and the light and flexible Hack rules allow quick resolution. Is this the last product for the Ghost Hack? I'm planning to revisit the two scenarios, which are edgy affairs, and republish them with more detail. It's in my mind to publish a scenario-and-campaign-setting combined: a haunted hospital.

But my main project this summer is Throuh The Hedgerow: don't miss that!

0 Comments

Behind the facade of normalcy, two forces contend. The farmer ploughs his field, sows the fertile seed. orders his land with neat hedgerows, tends fruit in the orchards, and blesses his family as they sit together at supper. This is the world of the Light. But at night, the Dark arises. The wolf scratches at the locked gates. The earth yawns open and disgorges the bones of the hungry dead that roam the lanes and lurk by stiles, waiting for the unwary shepherd hasting home, too late, far too late, as the sun slips from the hilltops and the night stifles his scream. Through The Hedgerow borrows this trope from classic fantasy - but notably from Susan Cooper's The Dark Is Rising series (and perhaps F. Paul Wilson's Adversary Cycle is rattling around in there too). With my professor hat on, I can tell you that it's a mythological concept rooted in ancient Zoroastrianism and termed 'dualism' by scholars. It's the idea that the world around us is an arena in which two cosmic forces contend: the Light and the Dark. Quite simply, the best Young Adult fantasy series, published in the 1970s and investing the British countryside with apocalyptic significance. It's been a huge influence on me. The Light is the force the nurtures: it is creativity, discovery, lawful and ordered living, perhaps life itself. The Dark is its opposite: destruction, ignorance, chaos, death. In Through The Hedgerow, the player characters have been plucked from their ordinary lives - or, in the case of Fay characters, their already-extraordinary lives - to serve the Light. They might not have chosen this service. They might resent it. It will certainly cost them dearly: at the very least, it will cost them their innocence. The Light & your DoomServing the Light means labouring under a Doom, which is a tragic (or at least bittersweet) fated end. You learn your Doom when you create your character. Perhaps you are fated to betray your companions, turn to the Dark, die defending someone you love, or settle down and lose all memory of the Light and the Dark and your erstwhile comrades. Each character has a Doom Die which starts small (d4) but gets bigger as your Doom draws nearer. That's not a bad thing though - you can roll your Doom Die for any Check or Challenge, so the bigger it gets, the more powerful your character is. Advancing the size of your Doom Die is like 'levelling up' in convention RPGs, except for the fact that you can retreat the size of your Doom Die later, which is 'levelling down.' Why would you want to do that? Well, read on. Your ultimate Doom also determines your Doom Trigger: a set of circumstances that reveals your heroic qualities, but also your destructive flaw. If it is your Doom to betray your cause, then your Doom Trigger occurs when you get up to something important behind your comrades' backs or against their wishes. A Doom Trigger only happens once per adventure, if it happens at all, but it causes your Doom Die to advance in size, so that d4 becomes a d6. It also makes your Doom Die 'unlimited' which means you can use it over and over and really rely on it. In The Lord of the Rings, the Elves have a Doom to depart Middle Earth and travel to the Undying Lands. For many, this is triggered by their first sight of the sea. Legolas experiences the 'sea-longing' when he arrives at Pelargir to battle the corsairs and hears the gulls. Art by Lorraine Brevig Relying on your Doom Die is a risky course of action. If you roll the highest possible number on your Doom Die, that also makes it advance in size. This also can occur once per adventure. This means even a starting character could trigger their Doom then roll the highest number when using their Doom Die and end up with a d8 Doom Die, which is quite a powerful asset. The Doom Die can also increase when you gain rewards at the end of an adventure. In fact, there's one reward that forces you to advance your Doom Die whether you want to or not. The starting character I imagined earlier could end their first adventure with a d10 Doom Die. Isn't that a good thing? Well, yes, insofar as it makes you powerful. Being able to throw a d10 at any particular Check or Challenge is a significant benefit. The problem is, sooner or later your Doom Die will advance past d12 size. When that happens, your character's Doom is at hand: you are about to lose your character. Your Doom Is At HandCharacters in Through The Hedgerow aren't at risk of dying on a routine basis. Even if they are defeated by a Challenge, they are usually just distracted or weakened or possibly captured. It's a rare Challenge that threatens to vanquish them, removing them from the adventure. Even vanquished characters can return in a future adventure: if the Judge allows it, the Light snatches its servants away from peril. There's no getting round your Doom, however. Once that Doom Die peaks, your character's story has come to an end. Through The Hedgerow imagines this Doom to be a collaborative process between the player and the Judge. The Doom should come about in a way that fits the theme of the adventure and respects the arc the character has been travelling. It might be brutal and tragic, or whimsical and bittersweet. Were you stabbed in the back by someone you trusted - or did you fall in love with the Elf Maiden of the Old Moor and decide to stay with her, renouncing your life of adventure? The Doom doesn't have to occur immediately and it might take place in the next adventure you take part in, which would allow the Judge to work your character's departure into the story in a dramatically satisfying way. But go you must! But what IS the Light?It's easy to represent the Light as a force of cosmic goodness and the Dark as diabolic evil. Even handled this way, there's room for a lot of depth in character development. Some Briar Knight characters will be idealistic in their service of the Light, but many are bitter or reluctant. Hodkins are human champions who served the Light in their own age and were gifted - or cursed - with immortality to continue their service across the centuries. They have lost their homes, families, loved ones, everything they knew, to become warriors in an unending war across time. For many of them, their eventual Doom is a blessed release, 'a consummation devoutly to be wished,' as Hamlet says. Buggebers are Fay monsters created to be minions of the Dark. Some have repented and seek atonement by serving the Light, some have offended their former Lords and the Light offers them protection, others are prisoners whose service to the Light is grudging at best. For the bird-faced Ouzels, serving the Light is a political manoeuvre in the Courts of Fayrie: some see themselves as knights and strategists in a grand campaign, but others seek personal reputation or the means to defeat ancient rivals in the struggle between their Houses. Peter Johnston's fantastic art for Through The Hedgerow brings these archetypes to vivid life. Hodkins of the Ages of Plagues and Thunder, a Buggeber of the Age of Swords, Ouzels of the Ages of Swords and Plagues. Dualism gets a lot more interesting as a fantasy trope when the Light and the Dark don't perfectly align with 'Good' and 'Evil.' The Light promotes or perhaps arises from human flourishing - but in a rather abstract way. The Light tends to focus on the achievements of certain 'great souls' throughout history, strives to protect extraordinary treasures or locations of beauty, or tweak the destiny of pivotal figures. It isn't concerned with the 'greater good' and is unconcerned with causing suffering to bystanders as it furthers its plans. Briar Knights might be sent to abduct a child from its parents and entrust it to new guardians so that the child will grow up according to an important destiny - but along the way a family has been divided and parents left bereft. Stories in Through The Hedgerow will often feature these dilemmas and part of the fun of roleplaying Briar Knights comes from exploring their reactions - from both mortal and immortal perspectives -to making these fraught decisions. Eventually characters will exhaust their idealism (if they started with any) and this is where the Doom comes in: there isn't only a game mechanism bringing your character's career to a close because Briar Knights end up seeking their Doom. Eventually, Briar Knights end up rebelling, or walking away, or finding their own corner of a friendly field to die in. The late great John Romita created this iconic cover in 1967. When I saw this as a child, it burned itself into my imagination: a symbol of the renunciation of power and the defeat of youthful idealism. What about the Dark?If the Light isn't entirely 'good' then what about the 'Dark'? Is it evil? In many ways, yes. The Dark employs monsters and undead that hate humanity or else regard mortals as chattel or dinner. But it's worth distinguishing between ends and means. Among the agents of the Dark are more philosophical villains, such as the inquisitors of the Witch Harrow and the emissaries of the Raven Margrave. These adversaries claim to have seen a vision of the future so dreadful that any means are justified in averting it, including retarding human progress, extinguishing inspirational leaders and art, and unleashing plagues and disasters. Even an immiserated humanity is preferable to what the future holds in store. Viewed this way, the Dark offers a home to servants of the Light who have lost faith. The core rules don't explore this in depth: the Dark is simply 'the Enemy' and its progress is tracked by an abstract Nemesis Die. The focus is on Briar Knights serving the Light, their encroaching Dooms, and the travails of their tortured consciences. I'm designing further expansions that correct this: the Coven of Curdled Cream is an organisation of servants of the Dark, antiheroes working in opposition to the heroic Briar Company of Sky and Furrow. And the Deep? And the Spire? And the High Magic too?The Light and the Dark are not the only forces at work in this cosmology. I'm designing expansions that explore the others. The Deep is the spiritual power of the primordial waters - and death, which lies within and beyond them. From the Deep come ghosts, revenants, and doppelgangers, as well as alien races that occupy the border between life and death. The Deep needs policing and the Light and the Dark collaborate on this: the Pardon of the Grey Haar is a team brought together by their respective masters to tackle incursions of the Deep. Along the Salt Strand is a planned expansion that moves the action of Through The Hedgerow to the coasts, islands, and rivers, to storm-lashed cliffs, fishing villages, and drifting ghost hulks. The Spire is the spiritual power of human progress - and the force of religion. From the Spire come Fiends who draw humans to them in devotion and set them to labour in factories and businesses, spreading city streets and chimney stacks that are the aisles and steeples of their churches. Here is another antagonist for the Light and the Dark to find common cause against; even the Deep rages against the binding of its riverways with bridges and charters. Out of the Rookery is a planned expansion that moves the action to the great city on the horizon of the Old Shires, in particular the slums, sewers, and rooftops, where the Fay and their mortal allies fight a guerrilla war against the stifling oppression of the Spire. Somewhere beyond these contentions - and perhaps reconciling them - is the elusive High Magic. Under the Hollow Hills is a planned expansion exploring the Otherworld of the Fays and a setting where Light, Dark, Deep, and Spire confront each other openly.

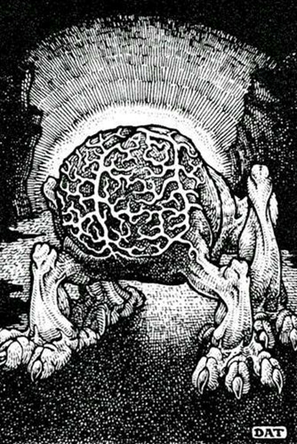

Back in 2021 I published a little indie game called The Hedgerow Hack. You might be able to tell from the name that it borrowed the rules engine from David Black's influential The Black Hack. You can read about the inspiration on one of my earlier blogs. Turning Hedgerow Hack into Osprey's Through the Hedgerow involved a fundamental re-think. Hedgerow Hack had its origins in an old school D&D session, albeit one with a rural and faerie theme. In particular, it was inspired by one player character from that game, a child cleric named Bilge who worshipped a scarecrow. Hedgerow Hack was created in the first instance to allow Bilge to have further adventures in a world that seemed more suited to him. Here (above) is Karl McMichael's original character art for Bilge. I was delighted when the talented Peter Johnston incorporated Bilge into the artwork for Through The Hedgerow - there he is, spying on the Cailleach as the brew their potions and lay their plots. With this origin, Hedgerow Hack followed the broad parameters of D&D: PCs were adventurers, they equipped themselves with weapons, they confronted the forces of evil with force of arms, combat was the central feature of most scenarios, albeit combat with talking squirrels and undead farm labourers, taking place in windmills, manor houses, or stone circles on hilltops, rather than dungeons. The tone was quirky, but it was still D&D at heart. With Through The Hedgerow, there was the opportunity to build a brand new rules engine and a completely different conception of what an 'adventure' might involve. What I wanted to do, was de-centralise combat. I discussed in a previous blog post the inspirations for Through The Hedgerow and they were the TV shows and fantasy literature of my '70s childhood. What I didn't notice as a child, though it seems so clear now, was the strong theme of pacifism running through them. Not just Dr Who (that was actually quite a violent show by comparison); the Tomorrow People were literal pacifists. In Susan Cooper's The Dark Is Rising, Will's great powers as an Old One cannot defeat the Dark Rider by sheer force; in Greenwitch, Will's fraught negotiation with Tethys is awe-inspiring, but it is the child Jane's act of compassion that brings about a resolution. But surely the best illustration of this theme that knowledge and imagination always trump power and force - so alien to 21st century children's storytelling, which is rooted in the violent fantasies of the Harry Potter series - is the wizard Ged's confrontation with the Dragon of Pendor in Ursula LeGuin's A Wizard of Earthsea: Dragon of Pendor by Wild-e-Eep on DeviantArt It only now strikes me that Marvel's Dr Strange (2016) stole this very scene, when Strange confronts Dormammu, saying, "I've come to bargain." It's hard to imagine how one could go about setting up a moment like this in most fantasy RPGs, where to be a wizard means having lightning bolts at your fingertips and a Dragon (or Demon) is, at the end of the day, just a problem expressed in terms of Armour Class, Hit Points, and damage output. To be fair, there are other RPGs that have experimented with de-emphasising combat, Tales From The Loop, for example. It's a good comparison, because Loop features PCs who are all children. Hedgerow likewise introduces PC 'Waifs' who are innocent children drawn into the battle of the Light and the Dark. It's absurd to place child characters in violent conflict and repugnant to places players and GMs in the position of sending children to violent deaths - unless you want to run some grimdark, amoral game; I could envisage (but not enjoy) such things in a horror or cyberpunk style game. What I felt Through The Hedgerow needed was a rules engine that allowed even potentially deadly encounters to be resolved using all sorts of abilities besides weapons and physical force: fast talking, bluff, trickery, emotional appeals, mystic pronouncements, running away and hiding, and courageous defiance. The Checks & Challenges SystemOutcome Checks In a game like Through The Hedgerow, PCs succeed at most thinks they attempt and dice rolls aren't necessary. Every now and then something happens where the outcome is truly in doubt. This is the time to make an Outcome Check. The PC rolls any one of of their relevant dice and the Judge rolls a Peril Die; as a player, you just have to match or exceed the Peril Die. This isn't hard: most of the time the Peril Die is a d4, or a d6 at most; something really horrible has to be abroad in the night to roll a Peril Die bigger than that. If you fail an Outcome Check, you don't find what you're looking for or get to where you were going. I'm a big fan of a House Rule which says that you can salvage the situation just by spending Resolve equal to the difference between what you rolled and what you needed. If you do this, a player can usually turn a bad roll into a success, but it's draining to do so. That's a pretty simple system. You, the player, choose the Die based on how you roleplay the situation. If you're trying to talk your way out of trouble, roll Charm; if you're hiding, roll Wits; if you fight your way out or just outrun them, roll Might; if one of your Virtues looks relevant, roll your Virtue Die - and of course, you can always roll your Doom Die. If you've got a useful piece of Gear, that let's you roll d8 instead, or perhaps d6 if it's only marginally useful for the problem at hand. ChallengesChecks are easy but sometimes the problem is bigger, more complex, or threatens very nasty consequences. This sort of problem is a Challenge and there's a different system for that. Every Challenge has a Threat Level (TL), from TL0 up to TL5. This indicates how many steps or episodes are needed to resolve it. Picking a lock might be TL0, just a single Threat, but being attacked by a pack of hungry wolves might be TL2, indicating three Threats in succession. I find myself wondering now why I insisted on calling the first Threat Level TL0 instead of TL1. There are reasons for it, but now that I look back, they don't seem like good enough reasons compared to the intuitive simplicity of saying that TL1 is a single Threat . Maybe future editions will correct this terminology. Players get to describe how their PCs deal with each Threat. In a sense, they become the games masters and take up the narration. You might say, "I pick up a burning branch from the fire and wave it towards the wolves!" or you might say, "I climb a tree to get away from them!" or even, "I look deep into the wolf's eyes and commune with its wild spirit." If it fits the situation and your character, you can describe it. The Threat then dishes out Peril, which is deducted from your Resolve score. This wolf pack might roll a d6 Peril, but the Judge might rule that climbing a tree is a good idea and the Peril shrinks to d4 for that character. If you don't want to lose Resolve (and usually, you don't) then you can roll dice to try to 'soak' the Peril. You can roll dice based on any relevant Quality, Gear, or Virtue. You can roll your Doom Die. You can roll a die for any of your personality Traits that apply. Using the burning branch might be worth a d6 (it's not really what the firewood is for which is why you don't get a d8 for it); climbing a tree might justify rolling your Wits Die; communing with spirits would use your Charm Die or perhaps your Gramayre Die, or both. You use the highest result and deduct it from the Peril, hopefully you won't lose any Resolve. This happens for the next Threat, and the next, until all the Threat Levels have been experienced. If you lose all your Resolve, you are defeated; if you're still standing at the end, you win, and the wolves retreat, or your escape them, or their leader submits to your authority. The catch is, most dice get exhausted after they are used, so for subsequent Threat Levels you have to change tactics, or else justify what you are doing in a new way. Maybe for TL0 you look into the wolf's eyes and roll your Charm and Gramayre. For TL1 you declare, "I'm overwhelmed by the beast's hunger and I stagger, but I find a reserve of strength in myself and maintain eye contact!" and the Judge agrees you can roll your Might this time. For TL2, you suggest, "I offer the wolf a sandwich from my satchel," and the Judge decides this is worth a d6 too. Assuming you didn't lose all your Resolve, the Challenge ends with the wolf leader devouring your sandwich, then the pack leaves you in peace. This is how a PC schoolboy can overcome the challenge of a pack of hungry wolves armed with a sandwich. Hazards, Humours & SuccessesSome Challenges don't just drain your Resolve. Hazards are penalties you suffer if you lose any Resolve to the Challenge. For example, the wolf pack might have the 'Injury' Hazard, which means that, if you lose even 1 point of Resolve, one of your own dice is 'burned' and is treated as a size smaller until you get healed. The Judge might ignore some Hazards based on the way you roleplay your behaviour. Climbing the tree or waving the burning branch around definitely risks an injury, but a sympathetic Judge might rule that communing with the wolf's spirit does not (at least not while you're using Charm rather than Might). Humours alter the way a Challenge works. For example, the wolf pack might have 'Armoured' which means any dice you use to soak their Peril that are based on force or combat are treated as a size smaller. Once you've passed all the Threats, you enjoy some sort of success, probably a 'Modest Success' which means the problem is over for now but it will soon return or be replaced by another one just as bad. You can make your Success more effective by generating 'edges' which you do by choosing to shrink you largest die before you roll it. Some Virtues and Gear also confer edges when used. Edges might turn a Modest success into a Minor, Major, or Outstanding Success. In the example above, the wolf pack might communicate important information to you before they leave - or even accompany you as an Ally for a while. Challenges generate 'notches' which counteract edges - one for each Threat Level after the first (which is why I call the first Threat 'TL0' as it generates no notches). There are Humours and Hazards that generate notches too. If you end up with more notches than edges, you enjoy only a Partial Success, a Bare Success, or No Success at all (which forces you to face the Challenge again). Putting It All TogetherThe Challenge System is very different from the turn-by-turn resolution systems of games like D&D. It draws some inspiration from Blades In The Dark's system that bundles all the various possibilities of a problem into a single dice roll based on position and effect, then ticks of segments of a 'clock' to mark progress towards a goal. Similarly, the Challenge System assigns a Scope value to the Challenge and to the PCs involved in it. A single person has a Scope of 1, two or three people would be Scope 2, four to six would be Scope 3, and so on. If the Challenge has more Scope, then the difference is used to increase the Threat Level or the Peril Die, or both. That TL2 Pd6 wolf pack from earlier might be Scope 2. A lone PC up against that many wolves might find the TL increased to 3 or the Peril Die increased to d8, whichever makes things more dramatic. You can ignore Scope when size and numbers don't amount to an advantage - climbing the tree, for example. In the same way, if the PCs have more Scope, they can reduce the TL or Peril Die. Four PCs confronting the wolf pack could reduce it to TL1 or Pd4. I've loaded the Challenge System with enough nuances to account for players who want to be armed combatants, so you can use it for big skirmishes or flamboyant duels (in the Princess Bride style). Martial characters can take Virtues which let them un-exhaust the dice they get from armour and weapons or earn extra edges with certain weapons or manoeuvres. For example, troll-like Buggebers count as two people for purposes of working out Scope and gain an extra edge when using their claws. Unlimited Dice are rare, but these dice don't exhaust until the end of a Challenge, so you can use them over an over again, against each Threat as it arrives. Your Doom Die becomes Unlimited under certain conditions. The Challenge System is also used for casting ritual spells or performing Glees (magical songs) or winning Riddle contests. RestingPCs will want to get their lost Resolve back and un-exhaust the various dice they used in Challenges. For this, there are different types of Rest. A Breather is a short rest. You spend a couple of minutes catching your breath, checking your injuries, restoring your concentration or peace of mind. You restore 1 point of Resolve and un-exhaust all your personal dice and the dice for any light equipment (including light armour and light weapons). Martial characters often un-exhaust other weapons or armour too. A Respite is a bit more protracted, more like half an hour, which means a chance to repair equipment, treat wounds, have a quick nap, etc. You restore all your lost Resolve and un-exhaust all dice. You can do special activities in a Respite, like cooking up schemes, hunting for herbs, or sharing a nice cup of tea (which lets you re-roll your Resolve, selecting the better result). The only catch is that, during a Respite, the dread Nemesis advances and the forces of the Dark get stronger. Fortunately, many characters have 'Free Respites' they can use to avoid this penalty. There are also Interludes, lasting several hours, in which mortals get to sleep and everyone can undertake more protracted chores. The Nemesis always advances during an Interlude. Adventures in Through The Hedgerow have a timer built into them. There's a Nemesis Die that starts quite small (like, a d4) but gets bigger every time you take a Respite and in other circumstances where the Dark gains power. When the Nemesis Die gets to d10 or d12, Challenges involving the Dark become especially difficult. If the Die increases past d12, the PCs have failed in their mission, but might be able to seek a final encounter with the Dark's powerful Emissary (and you'll need good luck to win a Challenge against one of them!). And then there's DefeatEven if you de-centralise violence, PCs will still sometimes lose and there need to be consequences for that. Not every Challenge involves the threat of injury or death, but something needs to happen. Then there's the issue of child protagonists who shouldn't be brutalised by the grievous outcomes that threaten adult combatants. My solution is to create a selection of 'Defeat Caps' ranging from 'Distraction' (you're a bit weak until you get a Respite), through 'Stricken' (where you burn your Dice until you get prop[er healing) and 'Capture' (where you're out of the story for a while) and ultimately 'Vanquished' (where you're out of the story for the rest of the adventure). In the example with the wolf pack, the character swinging the burning branch risks being Vanquished or Stricken (as the wolves tear into him); the PC in the tree risks being Captured (if she can't get back down); the character mystically communing with wolf spirits might be Distracted or Weakened. But even that isn't guaranteed. Players get to argue for a lesser Defeat Cap they find preferable and make a sort of saving throw called a Defeat Check. If ithe PC passes the Check, things work out as they describe it. PCs who are Waifs (child adventurers) can substitute being Captured for any serious Defeat Cap. Remember in the Lord of the Rings, where Boromir was vanquished, but the innocent Merry and Pippin were captured by the Orcs, only to escape later? This approach gives players a huge amount of agency. You get to describe the drama of the Challenges you face and select dice that match your description. Even if you are Defeated, the consequences of your defeat match the sort of drama you envisaged, and if you don't like that you still get a chance to substitute those consequences for more congenial ones. Does this make Through The Hedgerow a 'fluffy' sort of RPG where nothing truly bad ever happens to anyone? No, characters can be Vanquished easily enough. A lot depends on the tone the Judge wants to established: gritty and dangerous, or romantic and whimsical, or somewhere in between. Even Wind in the Willows has episodes of terror and danger: chapter 3 (The Wild Wood) places Mole in serious peril until Rat rescues him and they find safety at Badger's home. The eyes! Richard Johnson's excellent illustration of Mole alone in the Wild Wood with ... Them! Moreover, you can absolutely create martial characters: be-clawed Buggebers, tragic Hodkin, warrior-wizard Ouzels, grim Motley murtherers, and holy warrior Heathen Clerks. But even for these characters, combat can involve speeches, emotional appeals, curses, and dramatic flourishes, rather than just relentless pummelling. The point of these unusual rules that depart from the conventions of fantasy RPGs is that players are liberated from caution and concern over safety. You can confront the evil Witch-Hunters with a thundering denunciation, you can appeal to the honour of a crazed berserker, you can commune with the spirit of a ravenous wolf. Or at least, you can try and you don't need to be held back by the worry about what might happen if you fail. I recently had fun dusting off and refining my No Fear Psionics rules for Dragonslayer RPG. Now it's time to add the psionic monsters to the Dragonslayer roster - and that means an opportunity to reconsider these (largely underused) critters and their contribution to D&D over the years. Most of these monsters are familiar from the revered 1st edition Monster Manual (1977), although Githyanki and Githzerai turned up in the later Fiend Folio (1891). However, many of these monsters pre-date AD&D. They first appeared in 1976's Eldritch Wizardry supplement along with the first rules for psionics. In fact, Mind Flayers go back even further, to the first issue of Strategic Review in 1975. So, whatever you might think of psionics (and most people seem to think very poorly of psionics), these are 'core monsters' who perhaps deserve a little more love. Perhaps. Whoops!!!! I'd love to see a D&D monster manual from 1891, but we all know the Fiend Folio was from 1981. Thanks, Internet, for catching this one! The 'Psi Pests'This is a suite of monsters who function more as traps than as combat encounters. Think of them as 'psi pests' - the grit in the ointment of psionicism, inconveniences you have to take account of once you've become psi-aware.

In AD&D, these beasties drain your psionic defence points at quite a rate. You can't psionic them back: you have to dig them up and splat them (they've only got 1hp) or run away. Much merriment as the psionicist writhes, screaming 'Get them out of my MIND!' while the rest of the party grabs shovels to dig out these rodents and play whack-a-mole. Much less merriment if the victim is someone using psionic-style magic, in which case there's a solid chance of permanent insanity. It's a bit hard to imagine placing these creatures in a dungeon or wandering monster table: if you're not using your powers, they do literally nothing; if you are, then non-psionicists might end up losing a PC to them, while actually psionicists probably only face losing a lot of points that they can restore by resting. Cerebral parasites are mere annoyances. They attach themselves to you if you're using psionics or psi-magic while they are nearby and they drain your psionic power. Cure disease gets rid of them once you know they're there, so keep a cleric or paladin handy. I could imagine a cruel DM placing these things on a magic item or an infested monster, so the PCs acquire them during looting. Players will quickly realise what's going on as their psionic strength drains away - so if you don't like psionics but a PC has got them, infesting them with parasites is a great way of making sure they can't use their powers . The psi-variant grey oozes and yellow molds are entertaining twists on familiar monsters. Their psionic powers are pretty much one-shot-and-done, but I like the idea of a mold dominating a hapless psionicist and using them to attract more victims.

I've allowed Tower of Iron Will to count as an partial defence against thought eaters, just so that experienced psionicists can do something against these things - otherwise, ditch your armour and run away. Mid-Level Mind Menaces

The point is, if the psionicist accidentally summons these things with a mental shriek, her non-psionic comrades will be less than impressed!

Stross's original Githyanki were really just high level human fighters and magic-users (with a few anti-paladin bosses), hanging out on the Astral Plane, wielding OP magic swords, and riding red dragons, plus pretty fulsome psionic powers The Githzerai were boring by contrast - but then, pretty much anything is boring by contrast with that. I've toned down the swords (I mean, why would you make them intelligent as well?) and devised a simpler table for randomly generating a Gith band and their equipment. Essentially, this is a slimmed down version of the two groups suitable to be 'psionic wandering monsters.' I've made the Githzerai into monks and illusionists, to distinguish them somewhat from the Githyanki, and given both groups a resistance to mind flayers' anti-magic (otherwise, why on oerth would they specialise in being spellcasters?). Naming the silvery material they forge into swords and armour as orichalcum is a nod to medieval alchemy.

Next, it's those tentacles, which slurp your brain 1d4 rounds after a successful hit, no save.

I've toned mind flayers down a bit. In my 'No-Fear Psionics' rules, Tower of Iron Will is pretty good against psionic blasts, forcing the MF to roll to hit AC 0 against everyone protected by it - and then saving throws for the non-psionicists too. I allow you to whack the tentacle that's reaching for your brain, forcing it to withdraw. I've made their anti-magic a flat 1-5 on a d6 immunity - and I think PC spellcasters should be able to take a Feat like 'Astral Magic' that overpowers magic resistance, reducing its effectiveness to 1 in 6.

These monsters raise questions in my mind about what the original designers intended for psionics. Psionic combat gets very unbalanced when someone is outnumbered, which is probably why all of these monsters only turn up in groups of 1-4. Heaven help you if you end up in a Githyanki lair, because no individual can resist multiple competent psionicists coordinating their attacks. Mind flayers and intellect devourers seem to be designed to force you to engage with them psionically. MFs are practically immune to magic and the tentacles deter anyone from entering melee combat with them. IDs are pretty much immune to anything you can throw at them besides psionics. In other words, if you don't use psionics in your campaign, you can't reasonably deploy these iconic monsters, at least not RAW. Top Tier TelepathsWhen Eldritch Wizardry first introduced demons, a number of them were revealed to be powerful psionicists. It doesn't really hang together for me. Demons and devils seem to be the embodiment of clerical magic or sorcery, not SF-themed psionics. Psionics fit well with the alien mind flayers and their githian rebels. Why do infernal beings have psionics?

If the embodiments of evil are psionicists, then the avatars of good need to be psionic too. In EW, couatl, shedu, and ki-rin get psionic powers and titans are entirely immune to psionic attack. Then the Monster Manual goes and gives titans psionic attack modes too, which is dumb. Titans can wander into the infernal realms and psionically clobber demon lords are arch-devils and there's nothing the bad guys can do to them in return. Silly. Also silly is the lazy way couatl are assigned "9 to 16 clerical abilities with commensurate attack and defence modes" - the Monster Manual restricts it to 6 powers but retains the baffling reference to "commensurate" modes, whatever that means. Since Greg Gillespie didn't see fit to import shedu or ki-rin into Dragonslayer, I'm not going to bother either. I doubt anyone misses them. I've assigned some psionic stats to couatl and I recommend making titans fully immune to psionics, but without any psionic attack powers, as per original Eldritch Wizardry. Begun, the Mind Wars Have ...!?!If you have a psionic PC in your campaign and you use my No-Fear Psionics rules, you might decide to use the 'alarm' penalty for psionic misuse. This means that, once Psionic Stress builds too high, the psionicist discharges it in a psychic shriek that attracts psionic wandering monsters. This gets you over the problem of stocking dungeons with brain moles or thought eaters - they might turn up anyway if the psionic PC is careless or unlucky. This procedure implies something going on in the deep campaign background: a sort of psychic cold war: the Mind War. Obviously, the Mind War is being fought between the mind flayers and the githians, but secret societies and monastic orders will also be training their members and venturing into the psychic battlefield. At the highest level, maybe infernal and divine beings are the generals - or maybe the real warlords are beholders (ahem, eye tyrants) or duergar or dark elves, maybe nagas or sphinxes or even psionic dragons. PC psionicists start off encountering psychic predators and scavengers, but as they rise in power they start meeting the scouts and shock troops of the Mind Wars. You can try telling those Githians that you're just treasure-seeking adventurers, because they will reply that you only think that's wjhat you are, that your motives and memories are not your own - then they psionic blast you. High level PCs might decide to get involved in the Mind Wars. They will probably die before they figure out what's going on. It's not just the monsters being teleported into your fortress or your loved ones being dominated into killing you - it's the realisation that you can't trust your memories, that you may in fact be dreaming, that you cannot even be sure you are who you think you are. Damn - now I want to run a high level psionics campaign.

Through The Hedgerow is a RPG inspired by fairy tales, albeit odd ones. Four of the types of Player Characters are Fays. They are eldritch beings of the Otherworld who find themselves travelling the highways and bridle-paths of the Old Shires, carousing in roadside inns, hiding in ruined monasteries, or ruling their estate from ivy-crusted manors. How do you roleplay a Fay being? What are their motives and goals? Since they have their origin in fairy tales, here is the first of four tales to introduce the Fay Gentries of the Old Shires. Through The Hedgerow Buggeber by Peter Johnston The Tale of King Alfred and the BuggeberOnce upon a time, but not so far away, there was a King named Alfred, who had lost his Kingdom. The Kingdom was Wessex, which in those days was part of the Old Shires, and King Alfred had fought many battles to defend the Old Shires against their enemies. One by one, his friends and family died or deserted him, until eventually King Alfred could fight no more. Alone and humiliated, he fled to the fens of Athelney to hide himself. With night falling, King Alfred arrived at the house of the Fenwitch. He knocked on the door and the Fenwitch spoke from within: "Who's there?" Alfred replied: "It is Alfred, your King, armoured and armed to defend this land, and I need shelter to hide from my foes." "My little house is too low for so high a guest as a king," said the Fenwitch, "so you must set aside your crown if you would enter in." This Alfred did, though it daunted him to set aside his crown. "My little door is too narrow for so broad a guest as an armoured warrior," the Fenwitch continued. "Take off your mail byrnie and set it aside if you would enter in." This Alfred did, though it misgave him greatly to set aside his mail byrnie. "My little bones are too fragile," the Fenwife said, "to endure the presence of a guest armed with a sword. Lay your weapon down if you would enter in." Alfred debated with himself concerning this, for his sword Goldenhilt was an heirloom of his grandfather, who slew Beornwulf of Mercia. Runes were upon its hilt and jewels upon its pommel. Nevertheless, he laid it down. Entering the house, Alfred beheld a cauldron in which a meat broth was cooking, and an oven in which seed cakes were baking. art by Peter Jackson ©Look & Learn "What would you have, O King?" demanded the Fenwitch. "My broth is sustenance for a warrior, but my seed cakes are dainties for a land at peace. Choose." Alfred gazed upon the chunks of meet that bobbed within the broth. They were most appetising to him and the smell of it set his mouth watering. Nevertheless, he answered in this wise: "I have been a King of war and met only with misfortune. I will sample the dainties of peace, though it seems your cakes are still awhile to bake." The Fenwitch seemed pleased with this answer and instructed him thus: "Tonight must I go to visit with my sister in Cernyw. Abide you here, until my cakes are ready. But beware, for this night shall a monster visit this hall, the troll named Buggeber that hungers for mortal flesh. He does not wait on invitation. Do not let him sup from my cauldron, for if he does, he shall grind your bones to make bread for his broth." Alfred cried, "How shall I oppose such a fiend, having set aside my crown, my mail, and my sword?" But the Fenwitch made no reply, for she was gone, and Alfred was alone in the darkening hall. The long watches of the night passed slowly for the unhappy king. How he hungered to sup from the broth, but he remembered his choice to break his fast upon the dainties of peace. He prayed to the All-Ruler, but in this haunted place his prayers were mute. Then, at the darkest hour of the night, the Buggeber entered in. Old he was, that Buggeber, born in the ancient darkness, they say: one of the children of Cain, who carry the sign of the Murderer upon them to trouble a sinful world. Like steel were his long claws, like the pelt of a bear were his matted hairs, upon his neck there was no head, save only a maw of many teeth that gnashed and drooled. "Step aside, mortal man," the creature roared, "for I hunger. I hunger for blood, I hunger for flesh, I hunger for bones, bones, bones!" The Buggeber reached for the cauldron, his long tongue lolling down his chest. Up spoke Alfred, and these were his words. "I have a sweetmeat for you daintier than a witch's broth. A tall warrior, whose golden hair sways in the summer wind. Struck down, he is, by a sharp blade. Into the ground, his bones are laid. Then behold, he rises again." "Where is this wondrous warrior?" muttered the Buggeber. "For I see only you here, with no armour nor sword. Bring this warrior before me and I shall rend him with my claws." Then Alfred said, "It will avail you nothing, for he will rise again wherever his bones are laid. But look, I have captured him and crushed him and placed him in a small cell. Will you sate your hunger upon him now?" "Right willingly!" roared the Buggeber. "Bring me the warrior's body!" Whereupon Alfred took up a pair of iron tongs and withdrew from the oven the skillet bearing the seedcake. "But what is this?" howled the Buggeber. "This is not a warrior's flesh, but a cake of flour." Alfred answered him this: "The wheat is a warrior who sways in the summer wind. The seeds are his bones that rise again in spring. This cake is his body. Will you share with me now the dainties of peace?" Then Alfred and the Buggeber broke their fast together upon seed cake. In the morning, the Fenwitch returned to find her cauldron undisturbed and the fierce Buggeber now as meek as a newly baptised infant. She carved for him a face from a turnip in her garden. The Fenwitch counselled Alfred, "You have sojourned here a night, but a season has turned in the affairs of mankind. Behold, your kinsmen and vassals come seeking you. An army assembles: the men of Somerset, the men of Wiltshire, the men of Hampshire. Leave now, Alfred, you have a kingdom to rule." King Alfred departed from Athelney and lo! his army waited for him in the Somerset Levels. And it is said that the Buggeber went alongside him, who was now the most loyal of all the King's knights. Jack O Bear by Jrusteli on DeviantArt Buggebers as PCsRoleplaying a fairytale monster is cool, even more so if the monster is a hairy troll with claws and a carved turnip for a head. Not everyone will flee in terror when you approach. The Glamour is a magic that stops mortals from recognising Fays. Most humans see you as big and imposing, perhaps rather savage-looking and hairy, but they only see the monster if they look shrewdly, or with the eyes of Innocence, or if they brandish Cold Iron at you. Buggebers start off as Martial characters who can acquit themselves in a fight - especially with their size and claws. They are also Arcane characters with an affinity for Dark Sorcery, so they can use some of the more destructive spells without penalty. Roleplaying a Buggeber revolves around your Appetites, which are the things you yearn to eat. Each character has their own selection of appetites, which are all quite abstract: for example, a wild beast, something that's been dead for a long time, something that's been specially prepared. Given the game's themes of riddles and illusions, you can match these descriptions in odd and imaginative ways. Something with the insignia of a wild beast might satisfy you - or something that share the same name as one. Like other Hedgerow PCs, a Buggeber will have a Doom: this is a tragic or bittersweet destiny. 'Mastered By The Beast' means you will destroy yourself recklessly while 'Defying the Heavens' means you renounce the Light. Acting in a way that aligns with your ultimate Doom is empowering for your character: every time you do this your Doom Die gets bigger until eventually it increases past d12 size and your Doom is upon you. For Buggebers, the Doom is usually related to their status as demons of the Dark who have been co-opted by the Light. You are one of the 'good guys' now, but perhaps not willingly. You need to decide, how did your character end up serving the Light? Was she 'converted' by a powerful figure from history or folklore like Merlyn or King Alfred, Robin Hood, Shakespeare, Oliver Cromwell, William Wordsworth, or Winston Churchill? Did you 'defect' from the Dark after failing in a mission - or because you were troubled by the first stirrings of conscience? Related to this is your second question: what's your character arc going to be? In Through The Hedgerow, every PC is growing in power until their Doom comes calling for them. AS a Buggeber, you might be experiencing a redemption arc, where you discover friendship, love, or atonement - or an antihero arc, where you betray your comrades at the end and go back to serving the Dark. When your Doom arrives, you and the Judge must collaborate to decide what happens - so get thinking about it ahead of time.

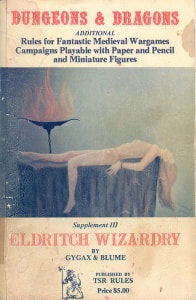

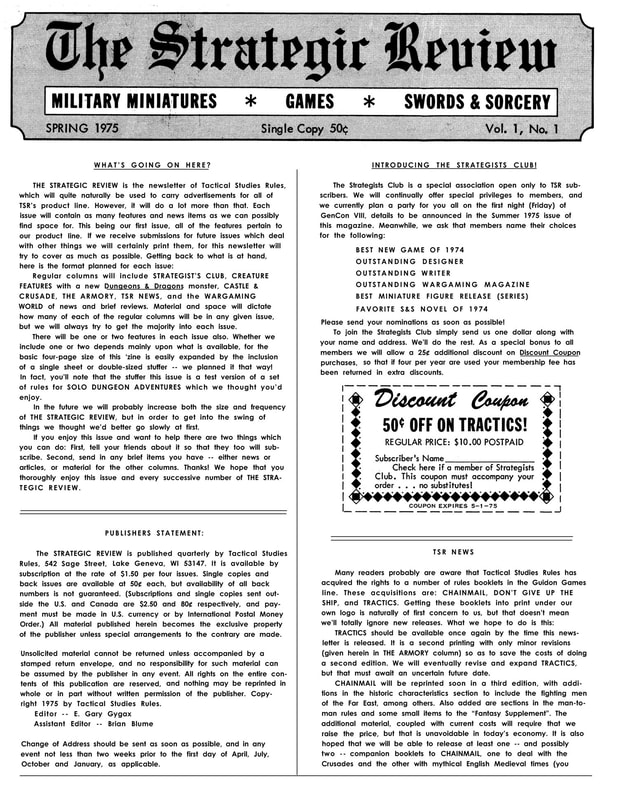

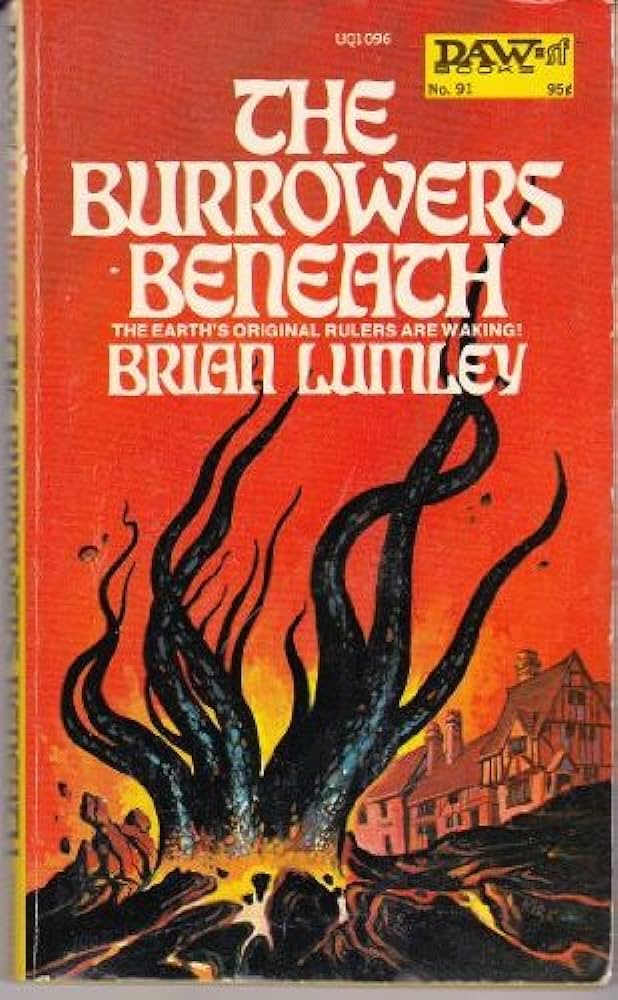

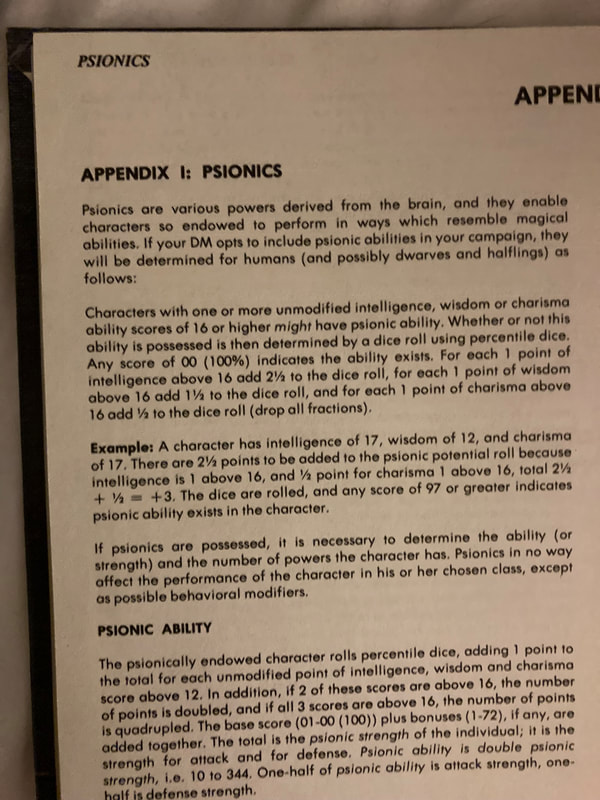

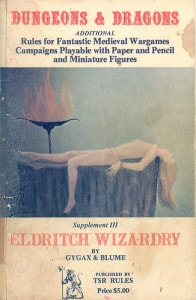

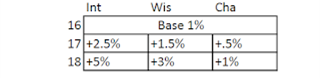

If you grew up with AD&D in the late '70s and early 1980s, creating a new character always concluded with a grim little ritual: rolling percentile dice to see if your character had 'psionic potential.' A roll of 00 would be cheering for the player, but elicited groans from everyone else: from other players, because their PCs were about to be overshadowed by a super-powered psionicist; from the DM, because an appendix full of fiddly rules was going to be imported into the first gaming session. Psionics were always an unhappy addition to early D&D, but they go back before my time, to 'Original' D&D (OD&D) and its third supplement from 1976, Eldritch Wizardry. The fateful appendix from the AD&D Players Handbook and (left) the source of all the mischief, Eldritch Wizardry The inclusion of psionics in OD&D is a bit mysterious, given that Eldritch Wizardry is mostly about Eldritch stuff (demons, relics) and wizardry (or at least, druids). It probably owes its existence to the influence of a certain sort of literature on 1970s fantasy fans: planetary romances like Marion Zimmer Bradley's Darkover novels and going back to Edgar Rice Burroughs' Barsoom series. These stories freely blended fantasy and science fiction tropes. Early D&D happily spliced high fantasy with SF or post-apocalyptic settings: an alien spaceship was the setting for a 1980 module and there were rules in AD&D for crossing over to Gamma World. For me, the perfect blending of psionics with high fantasy occurred in the pages of the UK Hulk weekly comic, which between 1979-80 featured The Black Knight, written by Steve Parkhouse and drawn by Paul Neary and John Stokes. This rather wonderful story placed the Black Knight in the Arthurian landscape he belonged in, resurrected (literally) the character of Captain Britain, and featured a dragon's pearl that granted psionic powers, culminating in a dramatic psionic duel over King Arthur's grave. I'm going to survey the original psionic rules for D&D, then offer my own 'No-Fear' Psionics rules for OSRPGs, in particular Dragonslayer. Psionics in Eldritch Wizardry

After that, there's more percentile dice rolling to generate your degree of psionic potential score and whether you get a minor psionic discipline or two, which are themed by character class. You get a single Attack Mode called 'Psionic Blast' (but no Defence Mode yet). As you go up levels, you can roll to get more psionic powers, including truly awesome major powers called 'Sciences.' As you acquire more of these, you gain more Attack and Defence Modes too. You also suffer penalties to your main class: Fighters lose Strength, Thieves lose Dexterity, spell-casters lose spell slots. Excelling at psionics means you don't excel at the other adventuring stuff. Psionic combat involves each side choosing their Attack and Defence Mode then cross referencing them on a table to see how many psionic strength points you both lose. Eventually, someone runs out of points, cannot defend themselves any more, and gets mentally whacked. Since strength points are used to power psionic disciplines, it's quite likely PCs won't be at full power when they run into a psionic enemy. Psionics in AD&DAD&D gets rid of psionic bans for certain classes and invites Halfings and Dwarves (for some reason) to join in the fun.

In many ways, Psionics is more powerful in AD&D, but only if you qualify for it (which is harder) and roll lucky (also harder). Psionic characters start off combat-worthy and able to use a minor power, but they won't get those major powers till they hit 'Name Level.' The disciplines are also more costly to use than they were in Eldritch Wizardry. Psionic combat works the same way as before, except it makes clear everyone uses the best Defence Mode they've got against whatever their opponent attacks with. The penalties for losing a psionic duel can be minor (dazed), severe (confusion), very severe (permanent idiocy, loss of powers) or outright death. The Pros and the ConsThe biggest objection to all this is theme. If you're not running a SF/fantasy hybrid game, then Psionics don't really 'fit' into D&D and their existence rather undermines clerical faith and wizardly scholarship. But if you're playing 5th ed. D&D and you've made your peace with Sorcerers then you won't care about that. The other objection is in the rules for Psionics themselves: not just their fiddliness (but that too!), but rather the jarring sense of disunity between the way Psionic combat and disciplines work (with its point-spend mechanic) and the way everything else in D&D works (with fire-and-forget spells and Hit Points as the universal constant). I object to another aspect of Psionics: the way they reward characters who are already lucky and powerful! If you've got 16+ in Intelligence, Wisdom, and Charisma, you've already rolled well (to say the least). Why should a character like that get even more perks? Then there's the percentile roll to see if you're gifted with psionics. Most PCs won't make it, but a lucky few will. Psionics isn't something you can build into a starting character, maybe at the expense of developing him in other ways. No, it's a flukey add-on that might be acquired by a character who never envisaged such an aspect - but unluckily denied to another character who was hoping for it. On the other hand, Psionic powers have their own appealing aesthetic - especially psionic duels. And of course there are entertaining psionic monsters that only come into their own if one of the PCs is psionically active.

Fen Orc's No-Fear PsionicsThese rules have been tweaked for Dragonslayer but will work with minimal tweaking for any D&D retroclone like Labyrinth Lord or White Box. The first step is to tie psionic potential into my system for Feats. Most PCs get to choose a Feat at 3rd level, but Humans get a compensatory Feat at 1st level, so could start with psionic potential right from the get-go. This potential isn't much: just a single Attack and Defense Mode, but since the Attack Mode is Psionic Blast you could use it to mind-whallop non-psionic monsters. After that, whenever you are eligible for another Feat (3rd, 5th, 7th level, etc.) you can choose a Psionic Feat that widens your abilities or strengthens you as a psionic combatant. This means Psionics powers come at the expense of other useful perks that could make your character more powerful or distinctive. Rather than fiddly points that score in the hundreds, you get a single Psionic Stress point whenever you use your powers (or 1d6 stress points if you use Psionic Blast to do the mind-whallop on non-psionic monsters). Whenever your Stress increases, roll a d6 and if you match or roll under your current Stress score, something bad happens. The bad thing that actually happens is a conversation you need to have with the GM when you choose Psionics - and it's based on the rationale for psionic powers in the campaign. Three options for Psionics Maybe psionics are a biological inheritance or a mutant gene. If so, the penalty might be simple exhaustion: you've pushed yourself too far and you can't use psionics again until you've had a good long rest. Maybe instead, psionics are blended with madness and accessed through taking strange narcotics or subjecting yourself to ineffable rituals. In which case, the penalty is that you go insane in some colourful way, until you rest properly and calm down. However, at least you can still use your psionics (erratically). Or perhaps psionics are achieved through Jedi-style training in some esoteric order, which inducts the young psionicist into the Mind Wars going on beyond ordinary perceptions. In this case, the penalty is that you've alerted hostile psionicists or psionic monsters: they perceive you and now they're coming for you. Whatever the bad thing is, the upside is that you remove an amount of Stress equal to the die roll that triggered it. Psionic Combat I wanted to keep the distinctive Attack Modes versus Defence Modes mechanic, but ditch the book-keeping point expenditure. Instead, cross-reference the Modes to find out the AC you are rolling to hit. If you hit your opponent, they gain a Stress Point; if they hit you, you add a Stress Point. As usual, roll a die when anyone's Stress Points increase but the penalty is determined by the Attack Mode used against them: confusion, stunned, charmed, coma, or dead. This sort of combat can be swing-y and very fast. Not just fast as in, it's all resolved and over before the fighter has drawn his sword or the magic-user has pronounced his spell. No, fast as in, it could end in a single exchange if a combatant gains a Stress Point and then rolls a '1.' To counteract this tendency, there is the option of increasing the size of your Stress Die (to d8, d10, or d12) and gaining 'psychic decoys' which can be expended to avoid defeat penalties - quite important to prevent a mighty Balor demon being mind-whalloped by a 1st level character who rolled lucky. Why Bother? Good question. If you feel that Psionics don't fit the fantasy vibe of your campaign, then keep them out. But if you're like me, then the presence of Psionics in the earliest iterations of D&D will tease your imagination. Part of the fun of OSR-style play is recreating the drama of the early days of D&D - and Psionics was part of that drama. The turn-off, as far as I was concerned, was in the fiddliness and book-keeping required and the unfair advantage psionics bestowed on already-privileged characters. I hope, by reducing the fiddly book-keeping and dependency on lucky d100 roll, this 'No-Fear' system will tempt a few gamers back into Psionics.

I wrote about the Detective class and adapted it for White Box in a previous blog. But I'll cover it again here before suggesting a different way of adapting it for Dragonslayer. Marcus Rowland - a stalwart of the UK RPG scene - contributed the Detective class to White Dwarf 24 back in 1981. Marcus Rowland introduces the class in these terms: The detective is a new AD&D character class whose functions are the solving of mysteries and the restoration of Law. This rather nicely fits the Detective into the mythic world of D&D, especially the Law-versus-Chaos theme of early D&D. Rowland limits Detectives to being Human, Elven, or Half-Elven, but that seems weird to me, given the Elvish link to (albeit Good-aligned) Chaos. Halfings and Dwarves are far more likely to be mystical enforcers of Law, but I would allow Half-races to dabble with Detective work, if only to allow the possibility of a Half-Orc chewing a cigar and growling 'Just one more question!' in a bad Peter Falk impression. In the world of Dragonslayer, Detectives seem to fit well as a Cleric/Monk sub-class. Rowland's prerequisites cover all six abilities, which seems too strict. If we base them on Dragonslayer Monks, then Dex 12, Int 15, Wis 12 seems appropriate, with Intelligence and Dexterity as the prime requisites for experience bonuses. Ability Requirement: Dex 12, Int 15, Wis 12 Race & Level Limit: Human U, Half-Elf 6, Half-Orc 5 (or U, if Colombo-themed), Dwarf or Halfling 7 (or U if Hercule Poirot themed) Prime Requisite: Intelligence & Dexterity Hit Dice: d6 Starting Gold Pieces: 40-160 (4d4 x10) Detectives have an attack progression and save as Clerics/Monks. Rowland lets them use chain mail and shields, but I think the Thief restriction to studded leather fits better. Any one-handed weapon is allowed: I don't see why Detectives should not use "spears, lances, flaming oil, and poison" as Rowland proscribes. This table adapts Rowland's class, with progression slightly slower than Clerics at first, but getting faster at high levels. Spells kick in at 3rd level (rather than 4th as in the original).

+ 200,000 XP and +1 HP for each level after 10th. Spells follow the pattern of clerical spells from a level lower (i.e. 5/4/3/3 at 11th level, same as a 10th level cleric) Role: Detectives are secondary fighters and scouts. Weapons & Armour: Detectives may wear leather or studded armour. They may not uses shields or two-handed weapons (except bows). Language: Detectives learn an extra language at 2nd level and every level thereafter. These languages can include Thieves Cant and Ancient Common. Saving Throws: Detectives save at +2 versus charm or emotion-control (including fear) Thief Skills: Detectives can Hear Noise, Climb Walls, Find/Remove Traps, and Appraise as a Thief of the same level. Starting at 3rd level, they can Hide in Shadows, Pick Pockets, Move Silently, and Open Locks as a Thief two levels lower. They cannot backstab. Disguise: Detectives can Disguise themselves as an Assassin. Tracking: Detectives can Track opponents as a Ranger, but only in urban or underground environments. In urban environments they must have seen the target within 2 turns (20 minutes) of commencing tracking. Underground, the chance of Tracking is reduced by 10% every time the target uses a staircase or secret door and 25% every time there is a combat encounter. Sage: When Detectives reach 10th level, they become Sages: treat as the ability to cast Legend Lore but only from his or her study/library/laboratory. By tradition, there is only one 10th+ level Detective in a city; if another arrives, the two must engage in non-lethal competition and the loser either leaves or becomes a non-adventuring consultant. Spells: Detectives gain quasi-clerical spells at 3rd level with a focus on detection and mystery solving (plus some spells aiding in escape). Like clerics, Detectives may not memorise the same spell more than once per day without use of a magical item. I've adapted Marcus Rowland's spell list, drawing in some of the Dragonslayer spells, generally making the spells a bit more impressive and abolishing expensive material components. 1st Level Detective Spells Comprehend Languages - as the 1st level Magic-User spell Date Duration: 1 round Range: 10 feet Cast on evidence (e.g. a footprint, a bloodstain, a picked lock) this spell reveals how much time has elapsed since an event related to the evidence took place. Detect Charm - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Detect Evil - as the 1st level Cleric spell (may be reversed at will) Detect Enemies Duration: 1 Turn Range: 10 feet/level The caster senses the presence of creatures who have hostile intentions towards him or herself (but not creatures that are merely dangerous to all passersby, like dangerous animals or plants or mindless undead). Detect Illusion - as the 1st level Illusionist spell Detect Lie - as the 4th level Cleric spell but cannot be reversed Detect Pits & Snares - as the 1st level Druid spell Detect Secret Door Duration: 1 round/level Range: 30 feet The caster automatically spots secret doors or secret compartments for as long as the spell lasts (and the caster may move at combat speed while the spell is in effect). Escapology 1 Duration: 1 round Range: touch The caster or the person they touch is instantly freed from ropes or simple bindings. The spell has a verbal component so the caster m,ust be able to speak to cast it. Feign Death - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Grade Metals Duration: 1 round Range: touch The caster becomes aware of all the metals that an object is made up of and their relative proportions. This allows a Detective to use their Appraise power successfully on precious metals. It does not reveal whether metals are magical, but it will detect the presence of mithril. Know Alignment - as the 2nd level Cleric spell Snare - as the 3rd level Druid spell 2nd Level Detective Spells Detect Evasions - as Detect Lies, but reveals evasions and half-truths as well as outright lies Detect Invisibility - as the 1st level Illusionist spell Detect Magic - as the 1st level Cleric spell Escapology II - as Escapology I but also works on chains and metal fetters Locate Object - as the 3rd level Cleric spell Read Codes - this improved version of Comprehend Languages translates messages in code or cipher into something the caster understands Reflect The Past Duration: 1 round per level Range: special The caster enchants a mirror which reflects events happening in the past at its location (up to 1 hour ago per level of the caster). Demons, devils, and demi-gods might notice and react to observation by this spell. Speak With Animals - as the 1st level Druid spell Speak with Dead - as the 3rd level Cleric spell 3rd Level Detective Spells Escapology III - as Escapology I but allows escape from metal boxes, riveted manacles, or otherwise 'escape proof' captivity; it also releases the target from the clutches, gluey secretions, or tentacles of monsters that trap victims ESP - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Forget - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Knock - as the 2nd level Magic-User spell Speak With Plants - as the 4th level Cleric spell Suggestion - as the 3rd level Magic-User spell Truth Duration: 1 round/level Range: touch The person touched must respond to all questions with absolute truthfulness; this might require a roll to hit if the target is unwilling and not restrained and if the caster misses the spell is wasted. Only innately deceptive creatures (devils, some faerie beings, etc.) are allowed a saving throw. Ungag - as Escapology I but has no verbal components and causes a gag to fall from the caster's mouth, allowing the casting of further Escapology spells; it also frees the target from monsters which have choking/suffocating attacks Vision of the Past - as Reflect the Past but creates a 3-dimensional image in a cloud of smoke and reaches back 1 day per level. Water Breathing - as the 3rd level Druid spell 4th Level Detective Spells Escapology IV - as Escapology I but allows escape from magical prisons (such as a Maze spell) Find The Path - as the 6th level Cleric spell Maze - as the 5th level Illusionist spell, but the range is Touch and the target receives a saving throw Oracle of the Past - as Vision of the Past but reaches back one year per level of the caster; if the caster goes into a trance they receive a vision going back one century per level, but this reduces the Detective to 1d4 HP when they awaken and wipes all other spells from the mind. Polymorph Self - as the 4th level Magic-User spell Read Divine Magic - as the 1st level Cleric spell Speak With Monsters - as the 6th level Cleric spell Stone Tell - as the 6th level Cleric spell True Sight - as the 5th level Cleric spell