|

I've spent time looking at the apocalyptic mythology set out in FORGE OUT OF CHAOS, as a basis for its system of Divine Magic, an explanation for its races and clerical classes and its (rather overlooked) implications for fantasy world-building. Time now to take a deep dive and explore the mythology on its own terms. Just what are its values and themes? After all, a myth, even a careless and derivative myth, is a tightly packaged bundle of meanings - it's an answer in story form to the fundamental questions of existence. So what answers do the myths of Enigwa's creation, the war between Berethenu & Grom and the Banishment provide? Tolkien & Kibbean Creation Myths

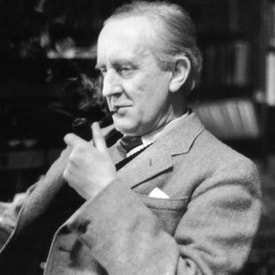

The Kibbe Brothers have clearly taken points from Tolkien. For example, in The Silmarillion (1977), Tolkien sets out the Ainulindalë (the Music of the Ainur) and Valaquenta (the Story of the Valar). A mysterious creator-God named Iluvatar brings the world into existence. Similarly, the Kibbes introduce Enigwa as the world-creator. World-creation is a task that Tolkien's Iluvatar shares with his created servitors, the Ainur or Angels. He delegates creative power to them, but one of them, Melkor, the greatest of angel-kind, pursues his own vision, disrupting Iluvatar's harmony, to which Iluvatar responds by deepening and complicating his symphony with richer themes to incorporate Melkor's rebellion into a satisfying whole. The Ainur are then given the opportunity to enter their creation and live within it as the Valar (Powers), i.e. embodied angels or earthbound gods. In the Kibbean creation-myth, Enigwa creates the world without collaboration: "he personally forged each mountain, planted each tree, chiselled each river." He then creates the gods and inserts them into his world so that they can "explore their father's creation.". Enigwa withdraws and the gods, left with autonomy, start to develop diverging agendas. "Although most were good at heart, some became chaotic, others aggressive, still others lustful and greedy." The gods fall into discord and Enigwa has to return and unite them in a shared project. There are apparent similarities here (creator-God, lesser divine offspring, rebellious autonomy, the Creator restores harmony). Tolkien, a devout Roman Catholic, created a myth that is purposefully analogous to the Christian one. Iluvatar is the Judeo-Christian God who creates free willed agents. He then adapts his creation to their free-willed choices, responding to their deviance with deeper and richer harmony, drawing beauty from ugliness, redemption from rebellion, holiness from hardship. Melkor of course is Lucifer, the errant angel. Tolkien's creation myth demonstrates why the creation of free-will necessitates the creation of a world, and a world which contains difficult features, but a world in which transcendent goodness is possible. The Kibbean myth is not Judeo-Christian but Darwinian. The Creator-God brings into existence, not free-willed minds, but a material world. Free-will emerges from Enigwa's absence, as rational beings explore the world through trial-and-error. It's a Behaviourist myth of learning through experience, of positive and negative reinforcement, with the gods developing in different directions, like B.F. Skinner's rats in a gigantic cage. There's no suggestion that Enigwa intends his divine children to evolve into these diverse personalities or even that he foresaw it. Although the text describes Enigwa as a "kindly father" he functions rather more like a dispassionate scientist: God-as-detached-observer. Unlike Iluvatar, he doesn't incorporate free-will and rebellion into his overall creative vision, he merely suppresses it when present and allows it to flourish when he is absent. Noxious characteristics in the world (deserts, miasmic swamps, volcanic rifts, predatory animals, parasitic wasps, diseases) are part of Iluvatar's compromise with free-will, but are outright distoetions of Enigwa's purposes, put there by his errant children. Free-willed agents don't seem to be part of Enigwa's plan so much as a surprising side-effect of it. Evil emerges from the absence of God or the failure of his foresight. In Tolkien, God's foresight is absolute and even Melkor's rebellion becomes the means by which a deeper, nobler and more surprising moral order emerges: "And thou, Melkor, shalt see that no theme may be played that hath not its uttermost source in me, nor can any alter the music in my despite. For he that attempteth this shall prove but mine instrument in the devising of things more wonderful, which he himself hath not imagined." This distinction, between Tolkien's divinely ordered but morally complicated creation and the Kibbes' disordered and lawless creation, leads to a different conception of Humanity. What a piece of work is man In Tolkien's myth, the created world awaits the birth of Iluvatar's physical creatures, the Elves. Most of the history of Middle-Earth is the history of the Elves: their journeyings, songs, romances and craftsmanship and - later - their noble but doomed war against Melkor/Morgoth. In Tolkien's Christian imagination, the Elves represent an Unfallen Humanity, Adam and Eve's children without original sin: immortal, virtuous, the peers of angels, the icons of God. Crucially, they're not boring. Immortality and goodness are compatible with having adventures, taking risks, experiencing peril, making mistakes. The Oath of Fëanor drives some Elves to to dreadful things, but apparently without malice. Humans appear later, a sort of divine afterthought. They are mortal, frail, unlovely and lack innate wisdom. They have one thing that Elves lack: the Gift of Death. An odd sort of gift, but one that relates them more fully to the Mystery of God than the Elves and even the Valar (who are bound to the world even if their bodies are slain). Humans are a paradox: the furthest from the divine in terms of innate power, the closest in ultimate destiny. And of course, mortality makes their brief lives into possible vehicles for self-transcendence. The courage and hope and faith of Humanity exceeds anything Elves can experience. This places Humanity in a clear Christian framework: humans are simultaneously central and peripheral, exalted and lowly, the highest and the lowest of creatures. It's an insight Shakespeare puts into the mouth of Hamlet:

In Christian thought, humanity has no innate value; humans are central to the drama of creation only insofar as they are loved by God, and loved insofar as they are sinners and suffer. In the Kibbean myth, Humanity is created by the gods as a shared project and entrusted to them by a departing Enigwa: "Help them learn of the world and its wonders. Instruct them as teachers and watch over them as shepherds." There seems to be folksy wisdom in what Enigwa does. To unite the querulous gods, he gives them a joint project and duty of care. One is put in mind of a parent giving squabbling children pet guinea pigs or hamsters and saying, 'You'll have to take turns feeding and cleaning them!' Regardless, Enigwa does not seem to know his children well. Once he departs, they fall to fighting again and this time their human pets are repurposed as warriors. Others gods come to Humanity's aid, but since they too employ humans as soldiers and raw materials for their ventures into species-creation, their advocacy is equivocal at best. Moreover, Enigwa leaves the gods with a parting instruction: a prohibition on teaching Magic to humans, "for Magic is the power of the divine alone and not meant for the ungodly." Of course, the gods violate this ban pretty quickly, promoting their human lieutenants to necromancers, elementalists and beast mages. This stands Tolkien's conception on its head. Humanity is now a central project on Juravia: the ur-species from which all other fantasy races are derived. However, there's nothing of the divine about them and no transcendent mystery to their destiny. They are a biological instrument, intended to unite the gods but retooled as weaponry. Humanity finds itself at the tail-end of a long story, present in the world to serve purposes not of its own choosing and shaped by contingencies set in motions aeons earlier. This is a truly Darwinian perspective. Insofar as there is a Fallen race in Kibbean mythology, it's the gods themselves, who renege on their duty of care and violate the prohibition on teaching Magic. Tolkien's rather nuanced Christian sensibilities appear here in a very debased form. There are people (not usually Christians themselves) who imagine the Genesis myth to be the story of an irresponsible Creator placing his human wards in an experimental environment with only cryptic guidance and allowing them to corrupt themselves through poor choices, then punishing them for disappointing him. This is certainly a good description of how Enigwa treats his children, the gods. In the last blog, I suggested the Kibbes had created a great myth for the Enlightenment: a myth for secular humanism. The gods experience temptation, fall, wreck the planet and meet with divine judgement. There's no repentance, only Hell or Banishment. Then they're gone. Humanity and its sister-species are left in possession of a ruined world, like tenants-turned-homeowners after the bank forecloses on their landlords. Tolkien conceives humans as bound to God through the inscrutable intimacy of Death and uses his Elves to explore ideas about what an Unfallen Humanity would be capable of (and therefore what fallen humans should aspire to). The Kibbes conceive humans as the product of an unguided evolutionary process, perhaps set in motion by God, but not controlled or monitored by him. In the Kibbean mythology, Death is simply the end and the worst thing there is. The shortcomings of the gods expose the destructiveness of religious ideologies: Berethenu, Grom and Marda are not viable role models. Religion was perhaps meant to instruct and shepherd humanity, but it failed in that and actively abused people until finally losing its grip with the advent of a godless world.

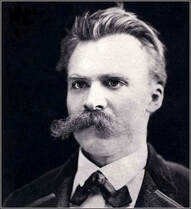

The mythological is political Of course a good myth doesn't have just one single interpretation (that would make it a mere allegory). There's a historico-political strand to Tolkien's mythopeia and a surprising (and creepy) political subtext to the Kibbes' mythopoesis too. Tolkien's Middle-Earth is meant to be our Earth viewed through a mythic lens. The parent civilisations of Classical Antiquity (Numinor) and Biblical Israel (the Elves) are represented as devolving into the murky Dark Ages of lost Arnor and waning Gondor. Gondor is Byzantium, the successor state to Greco-Roman civilisation and Biblical Israel. The Dunedain Rangers and their wards, the Hobbits of the Shire, represent the barbarian peoples of Northern Europe. They haven't inherited the physical accoutrements of the golden age cultures, but they are the custodians of its true values (liberty and Christian conscience). That's why "all that is gold does not glitter" in Bilbo's poem. Tolkien's understanding of Christian civilisation is pretty chauvinistic. Modern historians will point out that Islamic civilisation (very much 'the bad guys' in Tolkien) is just as much the custodian and conduit of Classical and Biblical culture as the Normans, the English and the Franks. The Kibbean myth can be interpreted historically too. Do the gods represent the imperial and theocratic powers of the Old World? Is the Banishment the First and Second World Wars, which toppled their empires and brought about the emergence of republican America, with its separation of Church and State? Berethenu is the British Empire, Crom is Soviet Communism and Necros is Fascism. Humanity, in this reading, means Americans. I feel pretty sure the Kibbes intended no such thing, but their myth does have an unpleasant aspect to it. I mentioned before that, for the Kibbes, Humanity is the ur-species; the Elves and Dwarves, the Ghantus and Merikii, all the lizard-folk and weasel-folk, they are all mutated Humans. In a sense, they are to Humanity what Tolkien's Orcs are to Elves: blasphemous remodelings of the original. Nothing could be further from Tolkien's thought, where the Elves are the Firstborn of Iluvatar and the other rational species (hnau as C.S. Lewis calls them) such as Dwarves and Ents are the independent creations of the Valar. Each has its own integrity and destiny. Not so in Juravia, where Humans are the true form and the other races are simply knock-off copies. Gary Gygax referred to the PC races in D&D as "demi-humans" but in Forge they really are demi-humans. Then you look at the illustration on p12 and - oh dear! - it seems that "the image of Enigwa" isn't just Human, but white people. Then you wonder, what about the lesser, corrupted races, the intellectually challenged Ghantus and the lizard folk and the ghost-faced Dunnar: who are they representing? Awkward... Of course, the Kibbes didn't mean to stumble into the back parlour of scientific racism, with its categorisations of 'lesser races' set against a White European norm. They were just weaving an entertaining tale, a "fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus" as Ron Edwards says. But it does go to show how loaded myths are, and how perilous it is to go tinkering with them. Easy to resolve. I like to imagine that the Kibbean myth in the Forge rulebook is just told from a human-centric perspective and that the Elves claim that they were the original species and the Dunnar claim no, they came first, while the Jher-em think everyone is descended from them. The true appearance of that original species, created by Enigwa and his divine children in a rare moment of harmony, will never be known.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed