|

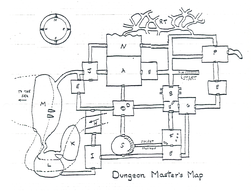

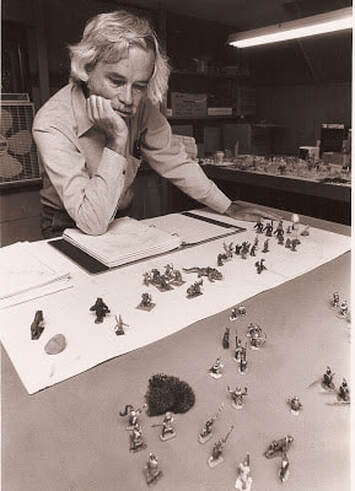

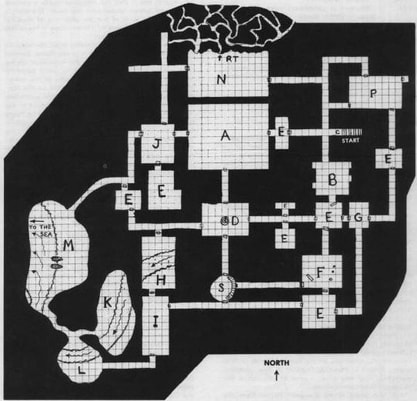

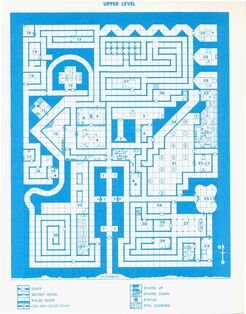

Over on the Scenarios page, I've posted up an adaptation of 'Tower of Zenopus' which has a special place in FRPG history. Back in 1977, TSR published the 'Blue Book' Basic Dungeons & Dragons set, written by Eric Holmes. Holmes was an author, psychologist and gamer who approached TSR as an outside writer with an offer to bring together their scattered Dungeons & Dragons rules in one introductory set. Gary Gygax's company agreed (Gygax himself was working on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons rules which would see print in stages over the next few years) and Holmes quickly created the version of the game that roleplayers of a certain vintage remember as their first introduction to the game - indeed, it was my first introduction. Gygax was a weird polymath with a fascination for medieval details but Holmes was the more orderly mind and, as an author, a better stylist to boot. In place of Gygax's long-winded and rather scholarly disquisitions, Holmes was the master of the poignant detail that lodges in the imagination. His 'Sample Dungeon' at the end of the blue rule book is a master class in early dungeon design that clear illuminates the way the hobby was to go forward - or perhaps, the way it should have gone forward, for Holmes' imaginative ideas were not all followed through by subsequent D&D output. Anyway: SPOILERS AHEAD - so if you're planning on playing through this iconic early dungeon, stop reading now before I give everything away. One hundred years ago, the sorcerer Zenopus built a tower on the low hills overlooking Portown.... So begins Eric Holmes' introduction to his dungeon adventure, setting the scene not just for a one-off scenario but, for many hobbyists, the guiding conception of what a FRPG adventure should in fact be: the template, the paradigm. Holes' introduction glances back into history, not just to a century ago with Zenopus, his tower and his ill-advised underground research, but further back, to "the ruins of a much older city of doubtful history," a phrase redolent of H.P. Lovecraft's eerie understatements. The glance backwards is also a glance outwards, to the graveyard nearby and the sea-cliffs facing "the pirate-infested waters of the Northern Sea." Readers are offered hints of three adventurous genres: swashbuckling pirates, necromantic graveyards and eldritch mysteries out of pre-human antiquity. If one of those doesn't float your boat, then what are you even doing here? Zenopus departs in grand style, with his tower engulfed in green flame by a nameless horror unleashed down below. Holmes adds further macabre touches: ghostly lights and ghastly screams and "goblin figures ... dancing on the tower roof in the moonlight." The last detail possesses a weird faerie poetry, like something out of folklore or nightmare, quite at odds with the prosaic direction D&D took under Gygax and TSR. We're treated to an account of the fretful town elders wheeling out a big catapult to batter the tower to rubble. There's a nice juxtaposition here of the secure life above ground, with its civil authorities and their catapults that put a stop to unsettling hauntings, with the below-ground world of the dungeon, the place of unanswered questions, of fatal ambition, a world of transformation: Holmes concludes with the image of "a flight of broad stone steps leading down into darkness." Do you stay up above in safety, in a "a small but busy city" with its fancifully named inn ... or descend and take your chances in the Otherworld of mystery and romance? You can tell Holmes was a psychologist. He might as well have called the town Ego and the dungeon Id. The Open Dungeon Design Holmes' dungeon - let's call it the Zenopus Dungeon, although he never names it - establishes a template for the open dungeon design, in contrast to the Monster Mountain dungeon I reviewed last week. 'Monster Mountain' was a cross-stitch dungeon laced with breadcrumbs to send players this way and that on a pre-plotted narrative. You might feel as though you are exploring and discovering, but really you are enacting scenes the designer has already envisaged: you, using the ladder to cross the moat; you, feeding your new gems to the frog idol and receiving a key; you, unlocking the door to find a treasure revealed. In the Zenopus Dungeon, there's no such plotting. It's a true sandbox. You can go anywhere and encounter the rooms in any order. Yes, some encounters are likely to precede others. Room A, with its goblinoid guards, lies nearest and directly ahead. Some encounters make more sense if discovered in a certain order: meeting the Magician and having him escape before discovering the basement to his tower. But even here, events are intriguing if they are sequenced differently. The tower is a more baffling but exhilarating discovery if you don't know who owns it. Other encounters tell different stories depending on the order they present themselves: encountering Lemunda the Lovely and her pirate captors before meeting the the hapless former-pirate who has been charmed by the magician, compared to meeting them afterwards. In an open dungeon like this, a number of narrative elements are in flux. The arrival of the PCs is a catalyst for change and process. At the very least, some evil inhabitants will die and prisoners be released. More interesting things can occur too: alliances against a common enemy, revenge against a hated foe. Holmes assumes that players will attack dungeon denizens on sight, but offers ideas in case they don't: the goblins will surrender when half their force is dead, the charmed warrior is a former-pirate whose curiosity got the better of him, the evil magician is trying to take over the dungeon, the ape who hates his cage, what becomes of the victims petrified by the magician's wand? ... Stories can emerge out of this but don't have to, which means that each group that enters the Zenopus Dungeon will create different outcomes that reflect their choices and values, as opposed to the Monster Mountain Dungeon, in which each group must experience a story, but always the same story. Space for the Imagination As a writer, Holmes knows that he will never surpass the pregnant image of the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness": everything that comes after will fall short of what we imagine is down there. So he wisely delays disappointing us. His dungeon is spacious and most of it is corridor. Once downstairs, there's a crossroads, with passages heading off into intriguing darkness, through shadowy archways or up to firmly sealed doors. Time for debate and dissension. Head north and the tunnels go on and on, then branch and twist around. Head south and there's a chamber of dark alcoves and a tempting opened door. Those that head straight on find empty rooms, more doors, more tunnels. These corridors are where the party form their marching order, arguing about who goes at the back, disagree about who's in charge. These dynamics are important, not least because, the whole time, anxiety is growing. When the party finally burst into a room to find armoured goblins, rattling skeletons or slavering ghouls, their will be a blessed release of tension and combat will come as a delight. So many dungeons forget this. Take a nostalgic look at Gary Gygax's 1979's D&D Module B2 (The Keep on the Borderlands) and look at the strangely orderly Caves of Chaos. They're packed so tight, with an encounter round every corner. Gary Gygax gives adventurers no space to roam nor time to let the dread grow. See how poky it is compared to Zenopus (underneath, left)? To be fair to Gygax, he also designed 1979's D&D Module B1 (In Search of the Unknown, above right), which is more Holmsean in its layout, with corridors to get lost in. But the direction of travel under Gygax is clear: away from the baroque and towards the modern, even the minimalist. Dungeons cease being metaphors for the labyrinthine unconscious mind; they become mere underground pieces of real estate. Thematic Compass The Zenopus map may be sprawling, but the geography is artfully themed. Up north is Horror Land: the Rat Tunnels, the ancient city crypts, skeletons leaping out of sarcophagi and alcoves, ghouls dining out of coffins and spiders in the ceiling, everything is jump scares and cobwebs. Down South is Wizard Wonderland: the magician and his tower and his vengeful ape, a talking mask and a rotating statue, a realm of puzzles and whimsy. Over to the west is Pirate Adventureland: an underground river to cross, me hearties, aye and a sunless sea, a giant octopus and smugglers belike with a beauteous prisoner, d'ye see? Players won't be aware of moving from one theme park to another, but the imaginative consistency has a cumulative effect. In Wizard Wonderland, players might roll their eyes at the rotating statue puzzle but by the time they reach the magic sundial and the talking mask, they'll suspend their disbelief entirely. In Horror Land, the crumbling decay and dusty despair grows in intensity from room to room, until the sudden eruption of a giant rat from the wall prompts the same alarm as a phalanx of skeletons. But once we enter Pirate Adventureland, real world dramas take over. How to cross a fast flowing river? Never mind undeath, you might actually drown? The appearance of the delightfully un-magical pirates in the westernmost cavern is well-prepared. The players are ready now to suppress a more conventional foe for a more worldly reward: the rescue of a powerful lord's daughter. Again, Gygax's B2 module comes off the worse by comparison. In the Caves of Chaos, regions are themed purely by the monsters living in them, but the kobold caves are exactly the same sort of place as the hobgoblin barracks. The monsters might acquire more Hit Points but there's no shift in genre. You could play through Zenopus' Dungeon in one (long) sitting and experience three broadly distinct chapters or acts, but I'd defy anyone to persevere with the Caves of Chaos for that long. The endless monster-bashing becomes wearying. The distinction is due to Holmes' psychoanalytical interest. His dungeon is the landscape of the mind, of dreams and nightmares and, over in the western reaches, of the Super-Ego, bringing justice to piratical lawbreakers and rescuing the innocent. Gygax's Caves of Chaos, despite the name, owe nothing to Freud or Nietzche. They represent our world, the dense urban sprawl, with the PCs as policemen or vigilantes or looters, acting out troubled 20th century fantasies of order and arbitrary power. Ways of Escape There are Rat Trap Dungeons, where the PCs at some point hear a portcullis crash down or a rockslide rumble past or a giant granite block slide into place and realise they cannot exit by the route they entered. Gary Gygax's Module B1 turns into a rat trap when an infamous pit trap drops the party down to the lower dungeon level. Everything changes from that point. Now, Hit Points and resources have to be curated carefully. The PCs are advancing into an uncertain future and don't have the luxury of wasting energy or ammo on unnecessary encounters. It's gripping. I'll look at two Rat Trap style dungeons in the next few weeks: Tamás Kisbali's 'The Golem-Master's Workshop' and Albie Fiore's 'The Lichway'. But Zenopus is not a Rat Trap Dungeon. Quite the opposite, there are lots of exits from the dungeon: from the coffin rooms through a dirt tunnel to the cemetery, through the sea-cave out into the ocean and up through the Magician's Tower to emerge blinking into a busy Portown street. One exit from each 'theme park' in fact, embodying the themes of horror, surprise and exploration. Holmes has a philosophy on his side. Old school dungeons like this are meant to be riddles, not sagas; sprints, not marathons. You dive in, hit it hard and get out, then heal up, re-equip and delve again. If you over-extend and get into a fight while too low on resources, well more fool you and an ugly death awaits. Since Holmes is very conscious of how he intends his PCs to function, he places these exits to facilitate the style of play he wants to see. No need to hike back to those forbidding stairs, risking Wandering Monsters; no need to keep entering by them either. That ominous invitation of the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness" won't stale with repetition because the players won't be repeating it; on the second session, they'll be re-entering the dungeon through the Magician's Tower or the sea-caves or even the cemetery. There's a lot to be said for understanding how your want you players to function and building your dungeon to reward that. Holmes adds multiple access points so starting PCs can make many short jaunts. Holmes the psychologist is also reorientating the players' reality. As long as the "broad stone steps leading down into darkness" were the dungeon's entrance, the distinction between this world and the Other, between conscious and unconscious mind, was clearly marked. But now the cemetery - death itself, or the fear of it - also leads into the subconscious playground and so do the "pirate-infested waters of the Northern Sea," showing that our political and economic anxieties and our interior struggles are not so distant. Finally, the prosaic street scenes of Portown lead directly into the dungeon if you know the right door to open. The unconscious waits round every corner, right under your everyday feet, and the experienced adventurer is the one who knows that best. That's what leveling-up means in a Holmsean dungeon. If you want to know more about the room-by-room experience of this dungeon, there's a great breakdown from RPG Retro Review. How does it play with FORGE OUT OF CHAOS? Forge conversion requires little analysis, since almost all the monsters (whether men, rats, skeletons, spiders, snakes or ghouls) are monsters in Forge too, with similar characteristics. The Giant Crab is easily substituted for one of the innumerable silly giant insects in the Forge bestiary, this time the one with the resoundingly banal name of 'Dweller'. In general, Forge monsters are slightly tougher than their D&D equivalents, but this is OK since Forge PCs are more resilient too, since their armour soaks up damage and they have access to casual healing from herbs and binding kits. This resilience can work against Holmes' underlying philosophy. Unlike a squad of Basic D&D noobs, even starting Forge adventurers can stand up to several encounters before armour gets shredded and hit points are low. They should be able to cleanse the whole dungeon in two journeys, especially if their first one is lucrative (i.e. they went north into Horror Land). This works against Holmes' in-and-out-again intentions, meaning that the multiple exists and entrances won't feature so significantly. To balance this out, I made a couple of alterations to the dungeon. One is to add a Wandering Monster table that sets the population in motion and re-stock rooms, which punishes PCs who dawdle and makes doubling back rather more problematic. One of the Wandering Monsters is a truly nasty entity: the Dungwala is one of the creepier (but still stupidly-named) monsters from the Forge bestiary. A sort of evil predatory mist, it envelops a victim, paralyses them and suffocates them, eventually vanishing with their corpse. Worse, this thing is only harmed by magical weapons. Forge characters have a few spells that surrogate for magical weapons, but more to the point Zenopus' Dungeon is full of magical weapon treasures, so successful adventurers should acquire the resources to deal with this horror. But perhaps the first times it shows up, it will take a life or make a wise party flee. It's presence seems to me to vindicate the lurking dread implied in Holmes' introductory text. I've named the magician and his bodyguard using the Holmesean name generator at Zenopus Archives. Lemunda the Lovely needs more consideration, since helpless damsels are a tired trope in fantasy adventure. To give Holmes his credit, he seems to envisage Lemunda joining a party of adventurers as a fighter rather than sobbing and begging to be taken home. Adding a love interest between her and Bru Preslap (the charmed former-pirate bodyguard) makes things more interesting. In Forge combat, you rarely kill opponents outright, so it's an option to defeat the magician's guard without murdering him. Whether the players choose to be so forbearing is another matter. Mezron the Mysterious, as I've named the evil magician, is a different proposition. In Holmes' dungeon, he was a 4th level Magic-User who could threaten an entire party with spells like Web, Charm Person and Magic Missile. Forge Enchanters aren't nearly as threatening, since their spells take 5 minutes to cast per level. However, since he's supposed to run away and fetch his petrifying wand, I figure that doesn't matter. I made the wand dependent upon Spell Point expenditure to discourage victorious PCs from over-using it in future encounters. I never liked the idea of charges in wands. Finally there's the 'Goblin Conversion' probem you always get in Forge. This time I went with Higmoni. I dislike casting them as the Orcish bad guys because they're a PC race that (I feel) deserves better than that. However, I'm over-using Cricky Hitchcock's Svarts and, in this case, Holmes does an interesting thing: he mandates that the goblinoids match or exceed the number of PCs, rather than a fixed number or random spread, and that once half are dead the rest will surrender. This means that the Higmoni offer a bruising encounter (combat against armoured PC-peer opponents in Forge is always tough), but one that gets cut short before too much harm is done. The PCs the have the option of dealing with the Higmoni 'as people'. OK, as duplicitous, backstabbing people, but that's people for you the world over.

2 Comments

17/12/2019 05:04:28 pm

This is fantastic. Like you I started with Holmes. I never played through Zenopus or ran it. But now I really, really want too. Maybe I'll make it part of my Basic-era campaign I have been itching to do.

Reply

This is a brilliant analysis. Thank you for sharing it. I found this through a link at Zenopus Archives.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed