|

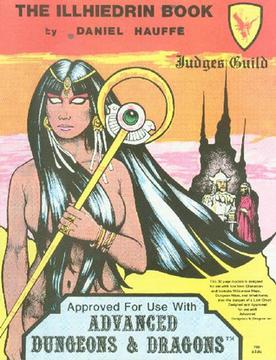

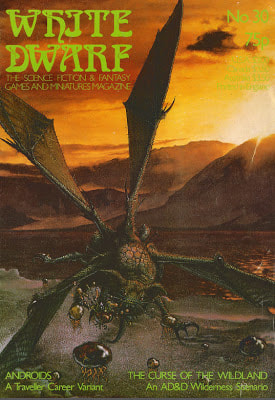

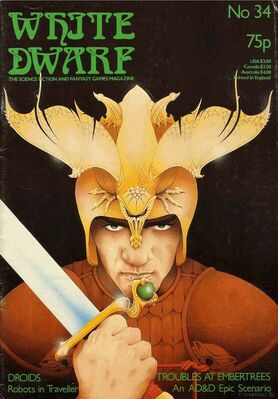

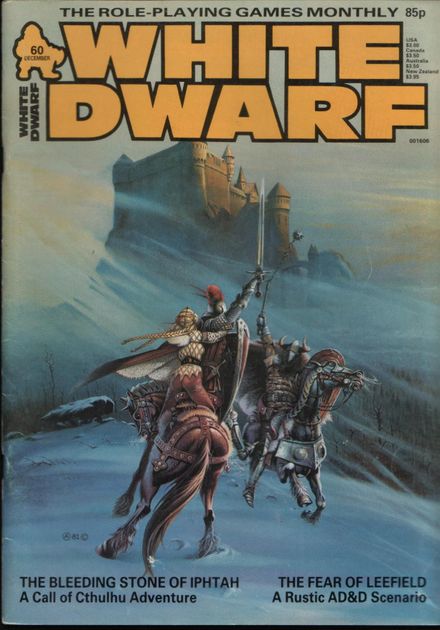

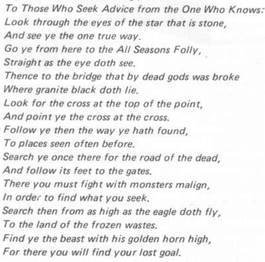

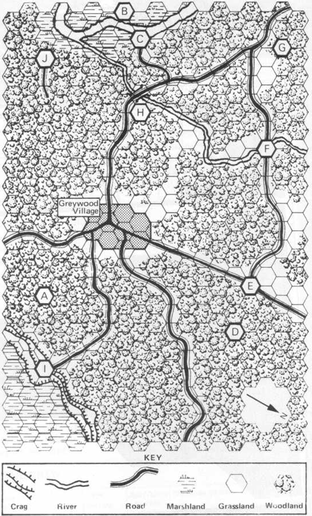

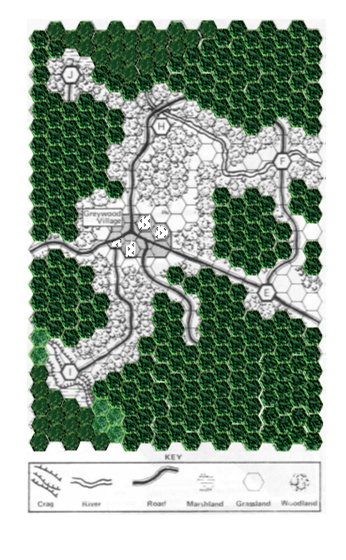

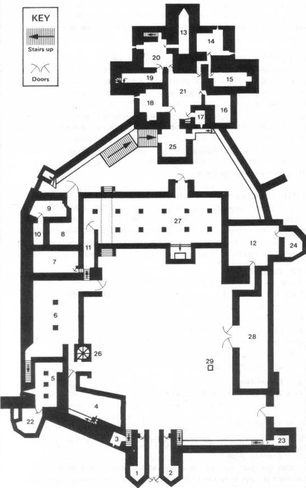

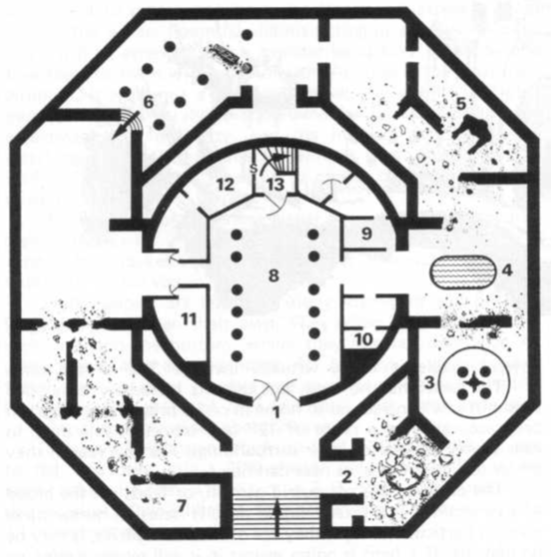

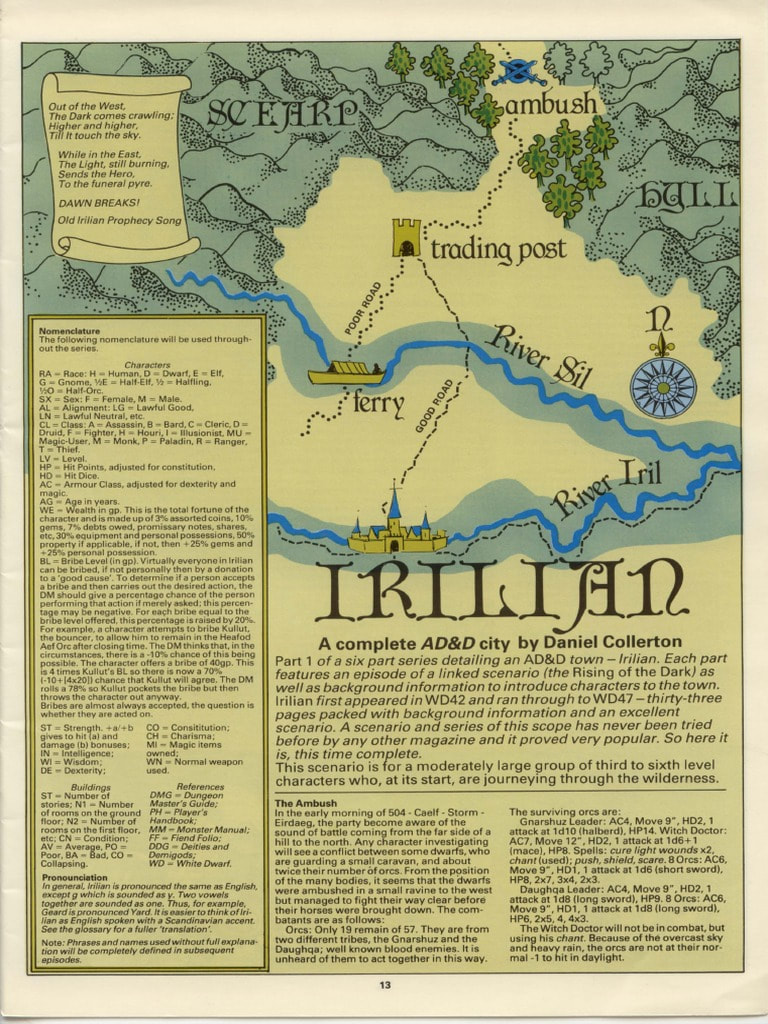

Like a lot of people, I like to celebrate my birthday by getting friends together for a game: either one of those big brainy wargames like Dune where everyone ends up in the kitchen, plotting, or else a jolly, feel-good RPG session, a sort of festive one-shot. Covid Lockdown imposes constraints on both activities, but the wargame more than most. So we gathered this afternoon to play old school D&D: five players and myself, talking through Zoom, rolling dice on Hangouts and me showing maps and floorplans by sharing a PowerPoint display. But what adventure to run? I'm time-pressed, right ahead of returning to work tomorrow, so it has to be a pre-made module. Time to dust off one of those old classics from the glory days of White Dwarf magazine. My eye falls on Barney Sloane's The Search for the Temple of the Golden Spire from White Dwarf 22 (1980). You can also find this mini-module in Best of White Dwarf Scenarios II Barney's adventure had always been a favourite of mine, although I'd never run it. How would it stand up, after all these years? I think, back when I was 13, Golden Spire impressed me immensely. This was no underground maze or skirmish in a fortress. Barney set out an attractive wilderness map extending around the village of Greywood, complete with ruined towers, Cloud Giant lairs, talking trees and a forest full of gnomes and sprites. There are two mini-dungeons to encounter. There's a riddle that serves as a coded map to guide players from one end of the wilderness to the other, culminating in the eponymous Temple where some very hardy monsters reside. The whole thing has a folkloric, faerie atmosphere that appealed to me greatly (and still does), brewing up elements of Spenser's Faerie Queen with its forest in which big evil temples pop out of the landscape and queer woodland folk offer cryptic clues. Remember, this was only 1980. This sort of above-ground adventure in an atmospheric wilderness setting was quite novel. B2 (The Keep on the Borderlands) only appeared the previous year and the wilderness segment of that was only a prelude to the real business of clearing out the Caves of Chaos, one goblin at a time. Usually, wilderness was just something to cross in order to get to the adventure: here it was part of the adventure itself, along with a small town-based segment as well. Although Jean Well's B3 (Palace of the Silver Princess) contained a wilderness element and a similar faerie vibe, it was (in)famously recalled and rewritten; the next product I would find with this sort of integration of setting and adventure, Judges Guild's The Illhiedrin Book, was still a year away. If you're my age, your adolescence is defined by either these covers or The Clash's record sleeves. Rereading Barney's adventure, 40 years on, I can see some flaws. It occupies that strange twilight zone between Original D&D and AD&D: creatures from the AD&D Monster Manual are referenced, but this is a OD&D adventure through-and-through, with little or no reference to the Dungeon Master's Guide's rules for wilderness travel, for example. There are confusions and omissions. What's the scale of the map? How far can PCs travel? How often do you check for Wandering Monsters? More importantly: just why, exactly, are the PCs seeking the Temple of the Golden Spire? Nowhere does the scenario explain what it is or why anyone would want to go there. It's sort of assumed that, once a Celtic Cross expounds a riddling quest, adventurers will just rush off and risk their lives to fulfil it on general principle. Certain aspects of the riddle are unexplained and there seem to be crucial details missing from the description of Greywood: what is the star that is stone? what's the deal with the abandoned house? what exactly do the clerics know about the Temple? what's the deal with Greycrag Citadel, visible on the horizon? You get the impression that Barney didn't bother setting down on paper everything that was going on in his campaign setting. Nevertheless, this scenario inspired a host of imitators in the pages of White Dwarf who corrected his mistakes, even if they never quite capture the faerie charm of Golden Spire: Phil Masters' The Curse of the Wildland (#32 and exemplary, like most of Phil's stuff) and Paul Vernon's Troubles At Embertrees (#34) were both from 1982; Stuart Hunter's The Fear of Leefield (WD#60) from 1984 and Richard Andrew's prize-winning Plague from the Past (WD#69) from 1985; all did a fantastic job of sending the PCs from a village in peril, through a cleverly constructed wilderness setting to a micro-dungeon showdown, but with a tighter plot and closer attention to AD&D rules. The thrill I used to get as a schoolkid when these things came thumping through the letter box.... It's not a problem filling in the gaps in Barney's scenario. He seems to intend some clue in the stone cross to send the PCs journeying down the road to the east. I introduced an evil presence in dreams that was recruiting villagers to the cult of the Golden Spire and the disappearing peasants act as impetus to investigate and the PCs' own nightmares make the stakes personal: if they cannot locate the evil temple and destroy its power, they too will convert to Chaos. AD&D, OD&D or ... gasp .... Holmes ???1980 was an odd time for D&D. The AD&D Dungeon Master's Guide had just been published - I acquired mine for Christmas in 1979 so it's quite possible Barney Sloane didn't even own it when he composed Golden Spire, perhaps using only the AD&D Monster Manual and the Original D&D rules set for his campaign. That would explain the odd, eldritch tone of his adventure. Back in 2020 I ran a campaign using the wonderful White Box rules, which do a great job of capturing OD&D. In fact, there's a huge section of this website documenting my attempts to reverse-engineer lots of character classes into White Box's delightful 10-level world. I promised myself I'd next turn to Blueholme next to capture the flavour of the Holmes Basic Set. But for this scenario, I wanted to try something different: the Blue Hack RPG. Three brilliant OSR rules sets - click on the images for links to purchase: PDFs of White Box and Blueholme are pay-what-you-want and Blue Hack is under £2 Blueholme and Blue Hack are both by Michael Thomas of Dreamscape Design. Blueholme is a straight-up retroclone of the Holmes Basic D&D Set, but the recent Journeymanne Rules expand the game to 20th level, introducing all sorts of PC race options beyond the basic Elves, Dwarves and Halflings along with lovely OSR art. Blue Hack is a different proposition. In just 22 pages, it condenses the D&D experience in the same style as the groundbreaking Black Hack RPG. You roll your classic 6 abilities on 3d6: Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Wisdom, Intelligence and Charisma. No modifiers or saving throws; if you want to hit something, you roll under your Strength on a d20; dodge an arrow, roll under your Dexterity; spot a secret door, roll under your Wisdom. Your class offers you Hit Points and damage is based on your class, not your weapon. Going up a level grants you opportunities to increase your abilities (try to roll equal to or over them on a d20). Monsters with more Hit Dice than you impose a penalty to hit or dodge them. Armour soaks damage. Every spell gets a single line of description; same with every monster. That's it. The rest is up to you. Blue Hack offers a few Holmesian tweaks to the Black Hack formula, like racial bonuses for the obligatory Dwarves, Elves and Halflings; some Holmesian spells and monsters; some refocusing of character classes. Enough to make it feel like 'Blue Book' era 1970s D&D. The beauty of this is the sheer speed with which you get a character up and running. You might think it's fast creating a character for Basic D&D, but there are hardly any tables to consult in Blue Hack. If you're creating characters online, over Zoom, this sort of pick-up-and-play ethos is invaluable. Blue Hack also suggests that PCs gain a level after every session/adventure/encounter - whenever the DM likes, really. With Golden Spire I wanted the PCs to start at 1HD (1st level) and rise to 3HD (3rd level) by the time they entered the Spire itself. This proved very straightforward - at various points, players got to roll and add those extra Hit Points, check to see if any abilities increased and expand their spell slots. Beautifully simple. So, what happened? [SPOILERS]Character generation throws up the usual adventuring misfits. David is a cretinous dwarven halberdier named Dimples; Emily an elven thief named Gnashe; Alex an elven fighter-mage named Azure-Wall; Oliver a good-looking human fighter named Gomez; and Karl turns to the macabre with a child cleric named Bilge who worships the god of scarecrows and communicates through a sock puppet.. This bunch don't ask for motivation: they study the riddle and get on with the quest. The tone is larky and riddled with Monty Python-isms: the villagers export walnuts and take everything literally, arm-wrestling resolves most interactions, cultists complain about itchy robes, no one believes gnomes exist. Not wanting to waste Barney Sloane's excellent scenario map, I moved it into PowerPoint for screen-sharing and covered the hexes with terrain-themed shapes, then deleted each shape as the party moved through the wilderness, revealing the map below. This was such an effective way of revealing a map and dramatising exploration, I'd love to do it for a round-the-table game, if such a format ever resumes. Yeah, you can probably do something similar on RollD20 ... The party discover Greycrag Citadel, infested with kobolds. It's a lovely castle map that I'll definitely re-purpose for future games. In this case, Gnashe sneaked in alone, found the viewpoint from the tower from which the Golden Spire could be located and the party covered her embattled retreat, chopping down kobolds and ghouls. Greycrag and the Temple of the Golden Spire: aren't those lovely? White Dwarf always excelled at scenario maps Heading to the Spire, the party have fun with wandering monsters: Yorkshire Centaurs and an Ogre teaching his son how to devour humans (feet first, of course). By the time they reach the evil temple, everyone is 3HD/3rd level and pimped enough to take on hard monsters, like a Harpy and the climactic Wraith (who of course drains several people of their levels before being pelted to death with the harpy's trove of silver coins). I decided that the introductory riddle was in fact sent by the Wraith, to lure the party to the Golden Spire and trick them into freeing him from his prison. It's a feature of Barney Sloane's old school scenario construction that, in his version, there's no explanation given for the presence of various monsters in the Temple of the Golden Spire: they're not doing anything, they're just waiting for adventurers to turn up and attack them. However, to his credit, Barney's kobolds in Greycrag Citadel are a fairly dynamic bunch, busy getting on with all sorts of interesting things when the PCs turn up: roistering in the big hall, torturing prisoners, sleeping on guard duty. That's another example of this scenario from 1980 being a sort of half-way house between the aesthetics of Original and Advanced D&D. Later, more sophisticated scenarios in White Dwarf in the '80s, by people like Phil Masters, would give careful thought to the presence of every monster and use them all in the service of an overall plot or theme. Overall, can Blue Hack really hack it?Blue Hack was a big success for this sort of level-up-as-you-go scenario. I'd love to use it for some of the old TSR Modules: Tomb of Horrors, maybe? or White Plume Mountain? Or dust off some later, more complex White Dwarf adventures, like Daniel Collerton's fabled Irilian city/campaign (WD#42-47). I'm not sure Blue Hack would serve for a conventional campaign. The roll-against-your-abilities system means that characters with high Strength or Dexterity will rarely miss - or get hit - in combat, even against tougher monsters. For example, with Strength 17, Dimples the Dwarf was hitting monsters with the same HD as him 80% of the time. How many 1st level characters in ordinary D&D have those odds? Without Armour Class, monsters enjoy some protection from damage, but a party of PCs can pile on the damage quickly, ending fights in just a round or two. Now, I quite like that - nothing is more boring than one of those OSR D&D fights that just goes on and on - but a sense of peril is lacking, especially as being reduced to 0 HP only has a 1-in-6 chance of killing you assuming the rest of the party survive to rescue you. The other feature is that, without experience points being needed to level up, PCs have no motives to seek out treasure. You might feel that's a good thing too: let adventurers be motivated by more realistic concerns, like duty or honour or saving the realm or rescuing loved ones. But it's surprising the amount of D&D material that's predicated on treasure as a motivator and if the PCs don't need to acquire it, all sorts of scenarios, traps, dilemmas and rewards need to be re-thought. Of course, you could easily paste a basic XP system onto Blue Hack to restore that mercenary motive. I think Blue Hack will be my system-of-choice for D&D one-shots, especially re-vamping old scenarios. It fast set-up and rather abstracted combat system makes it ideal for online RPGing. I like the fast fights and the option to assign level-ups at dramatic moments, rather than tracking XP. Its lack of 'grit' or peril might be a drawback, but it offers a fresh perspective on those old-school modules and scenarios. Did somebody say C2: Ghost Tower of Inverness? Let's go get that Soul Gem!

2 Comments

K.Mc

4/1/2021 05:36:57 pm

As one of the gallant adventurers...

Reply

DAMMY

1/7/2022 10:35:55 pm

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed