|

Previous posts discussed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic and analysed its apocalyptic mythology, in which the gods are all banished or consigned to Mulkra (Hell). This mythology, which gets pride of place at the very start of the book, was subjected to Ron Edwards' withering critique about fantasy heartbreaker RPGs indulging in "dumb names" and "un-fun strictures" for clerical characters. Edwards also complains that, despite their enthusiasm for myth-making, these games don't develop fantasy religion any further than a "direct correspondence with player-character options (as opposed to societies or organizations)." In other words, the myth-making just offers an explanation for fantasy races and clerical spells, but gets forgotten about as soon as this is over and done. Let's take a look at that. Life after the Apocalypse The Kibbe Brothers make a substantial and rather imaginative effort to sketch out a fantasy mythology for Juravia, involving a benevolent but absentee Creator and a family of flawed and compromised divinities, culminating in an apocalypse where the deities are judged, found wanting and banished. The implications of this are huge. Most fantasy mythologies - and many real world ones - propose an apocalypse at some future point. The Norse anticipated Ragnarok when the gods will fight the giants and lose. The Aztecs feared something similar and made blood sacrifices on an industrial scale to delay it. The word 'apocalypse' means 'revelation' and is the original name for the Book of Revelation in the Bible, an obscure rant in uncouth Greek where a prophet named John describes (with great relish) the ghastly things that will accompany Christ's Second Coming in a series of mind-bending dreams involving giant angels, many-headed monsters and environmental catastrophes.

The implications of this are huge and not just for who clerics get their spells from. Consider the explanatory power of religion. In ancient cultures, disease and adverse weather, crop failures and pestilence, these were explained by the activities of the gods, either through their negligence in making the world secure against chaos or their active malevolence. That's why you prayed and sacrificed: to get the divine 'on side'. This affected social structures. Society was set up to mirror a divine order, with a monarch supported by a priestly class, receiving authority from the gods to rule and resist chaos as their semi-divine representative or partner. Defying the ruler was defying the gods and siding with the powers of chaos, disorder and death. This focus on divine order doesn't just lead to rituals of kingship, titles and authority; it imbues the calendar with mean, allocating feasts and fasts to different seasons and drawing communities together to reenact the great myths in worship and art. Social order emerges from this and also social distinction: tribes that honour strange gods and indulge in senseless rituals are the 'Other' and conflict between tribes becomes part of the divine order too: warfare becomes a religious duty and death in battle a religious sacrifice. Now let's look at Juravia. What authority can kings and princes cite when some enterprising peasant asks (Monty Python style), "Well how come YOU get to be king then?" What institutions exist to prop up their rule with a claim to possess, not just might, but right? How should the inhabitants start to regard each other, now that it is known as an objective fact that their differences of culture and race (bird people, reptile people, giant one-eyed apes) are the result of self-interested power-grabs by a clan of squabbling super-beings who were all equally criminal in their actions. If praying doesn't solve anything, but the world still contains danger, bad luck, unfairness and outright wickedness, what are thoughtful people supposed to do about it? Actually, it's not hard to answer that. You only have to look at our world for answers. We too experienced a widespread cultural collapse in confidence in religion to provide the rationale for politics, social order and morality. It was called the Enlightenment. Life after the Enlightenment The Enlightenment roughly corresponds to the 18th century in European history and involved the light of reason and science driving out the darkness of tradition and superstition. There were lots of causes. The Protestant Reformation had helped make religion a private rather than a public matter and the bloodcurdling Wars of Religion shaped a view that God had no place in politics and perhaps no place in ethics either. Science arose to claim an alternative explanatory power to religion and leaps in technology seemed to validate scientific claims to understand the true nature of the universe. Forge's legendarium has similar forces at work. The God-Wars serve to discredit the gods and their worship, revealing that the gods were neither wise nor good and that they are no longer able to answer prayers. After the Banishment, mortals work out the principles of magic and learn to cast spells without divine assistance: a close analogue to the rise of science. Magic seems to be a natural (and morally neutral) force in the universe which can be manipulated by those with the intelligence, willpower and the right tools. The gods were just better at it than anybody else. The thinkers of the Enlightenment and subsequent centuries were faced with the problem of living in an imperfect and unjust world, without the assurance that God ordained it to be this way or would intervene to improve it. This is similar to the inhabitants of Juravia, left with a world with all the normal dissatisfactions (poverty, disease, inequality) plus marauding monsters. Fantasy Democracies and other solutions The most influential solution proposed by Enlightenment thinkers was human rights and democracy. In the absence of God, we have to be gods to one another and treat each other as gods. Every individual is accorded a transcendent worth and their consent (in some form) is the only ethical justification for the exercise of power and the continuance of unequal social arrangements. You would expect a world like Juravia to start throwing up democratic republics, where having the status of a rational agent (regardless of your appearance: bird-person or one-eyed gorilla) entitles you to vote. These republics wouldn't necessarily be very stable or even peaceful places. Democracies can be fissiparous and inclined to go to war, especially against non-democracies. You would expect slavery to be a raging controversy and some races might be unfairly deemed 'irrational' and unworthy of the franchise (I'm talking about those dimwit Ghantus). But democracy isn't the only Enlightenment solution. The fact that democratic republics can coexist so easily with the unjust social arrangements that preceded them explains why some people find them no solution at all. Communism offers another way, especially since the Banishment has created a Year Zero and an opportunity to cast down and re-make all social institutions. Agrarian fantasy societies might find Communism much more amenable than democracy, especially if they have to knit together different (and formerly inimical) races. It's easier to get the orcish Higmoni and the avian Merikii to coexist if you take all their possessions off them and redistribute everything. I imagine the frail but empathic Jher-em weaselfolk would excel as Communist commissars. The daylight-hating, magic-detecting Dunnar would rise through the ranks as well, leaving Elves and Dwarves to toil in the mines and collectivised farms. Then there's ethno-nationalism; let's just call it Fascism. Even if the gods are losers and now ineffective, having a specific creator binds fantasy races into a shared narrative, having a place where they belong and a way of life that is ordained for them: they are not just a species but a Nation. "We are Merikii, the People of Marda, and we were granted this land." Nations need borders and a strong sense of who is in (your compatriots) and out (foreigners). At its best, this produces communities with a powerful sense of identity and distinctive culture that is not subject to any sort of rational critique. At it's worst, there's institutionalised racism, enslavement of lesser species and genocide. Finally, there's the true flipside to the Enlightenment: religious fundamentalism. Not everyone accepts the gods are gone, no matter the evidence. Fundamentalism thrives on conspiracies and messiahs: either the gods are hiding themselves (as a test of faith, no doubt) or are shortly to return (to reward those who stayed loyal). Fundamentalists hate the democratic republicans, Communists and Fascists equally: they've all replaced religious worship with a false idol (the will of the people, the common good, the nation). In Juravia, where specific gods created specific races, Fundamentalism might coexist with some forms of Fascism. Maybe the Sprites await the return of Omara to rule over the pastures where she established her little people. In return, the Enlightenment political institutions distrust Fundamentalism. Democracies try to lock religion out of politics (either with a strict separation of church and state or by neutering religion as an established church that serves the state); Communism tries to expose it as a sham; Fascism might patronise some local cults while persecuting other foreign ones. Outright Atheism emerges from this debate. After all, why suppose the old stories of the gods are even true? Maybe Necros was just a way-powerful Necromancer and Dembria an Enchanter. They bamboozled people into thinking they were divine then got their comeuppance. "I'm sure there's a magical explanation for all this, Mulder." Dembria (Enchantment), Kitharu (Nature) and Marda (Beasts) Where does that leave the 'churches' of Berethenu and Grom? After all, these cults have some evidence (in the form of clerical spells) that their gods are still real even if they don't intervene. As sketched out above, some states will try to privatise these cults (whatever you do in your own time...) and others will assimilate them (this document makes you a state-licensed activist of Grom) or repress them (was that an act of ideologically-unsound magic, Friend Citizen?) and in some ethno-nationalist enclaves the cult IS the state (the Dwarvish See of Berethenu welcomes careful waggoners). Atheists will regard 'divine magic' as a hoax: ordinary Pagan Magic with delusions of grandeur. Of course, for ordinary people, there's ordinary superstition. It never hurts to offer a prayer to Kitharu before a sea-journey: if the god still has the power to make it tempest-free, so much the better; if not, what did it cost you? But I can't help feeling that a world like Juravia would be intolerant of such things. Once you reject religion, you don't tend to retain an affection for it, even in its quaintest forms. Since Kitharu infested the deeps with sea monsters and then cleared off, leaving the mess behind, I doubt sailors or the rulers of maritime empires would be sentimental about him. If you want a safe voyage, hire an atheist Elementalist; if you want to tell yourself comforting lies about Kitharu, stay on land. The culture of moderation and litigation The Kibbes' mythology seems to teach other lessons its writers don't appreciate. It condemns any form of extremism. Left to their own devices by Enigwa, the gods pursue their own agendas, becoming more and more extreme until, unable to compromise, they go to war. Obviously, Grom and Necros are the villains, but the tale of Berethenu is poignant. The god of Justice, Berethenu breaks all the laws he was trusted to uphold. He goes to war on the Triumvirate, he shapes humans into his Dwarvish servitor race, he teaches magic to mortals. Of course, he does so for high-minded reasons, but so what? When Enigwa pronounces judgment, Berethenu's own inflexible scruples make it impossible for him to repent: he condemns himself to eternity in Mulkra. The moral: there's no ethical difference between a monster like Grom and a paladin like Berethenu; both end up in the same place. One imagines that, even centuries later, the citizens of Juravia feel discomfort around a Berethenu Knight. Sure, it's nice that they give to charity. But the defining myths of this world condemn what they stand for. The myths also condemn laissez-faire individualism. Enigwa is culpably irresponsible for leaving humanity at the mercy of the squabbling gods. If the gods themselves cannot be trusted to run the world without the firm hand of higher authority guiding them, what chance do ordinary people have for making the right decisions unassisted? One suspects Juravia is a world of authoritarian regimes where people look to strong leaders and distrust liberalism. Even democratic republics can be authoritarian, especially if they are intensely legalistic. The law makes a great surrogate for religion in secular societies because it tries to do the same thing as religion: establish order and the limits of what is acceptable, create the illusion of control over the vicissitudes of life, pronounce judgment by rewarding the virtuous and punishing the wicked, connect people to the past through precedents and each other through contracts. I wouldn't be surprised if Juravian adventurers need to be legally recognised professionals, rather Elizabethan players, subject to the bureaucratic whims of a Master of Dungeons who hands out and revokes the licenses to plunder any particular tomb, cavern or mine, Or just ignore it Ron Edwards notices that Forge Out Of Chaos ignores all of these considerations. He actually takes it as a point in the game's favour that "this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." The Kibbe Brothers seem to bear this out. No sooner have they described the Banishment than they are alluding to the persistence of entirely conventional religion in Juravia. Apparently "sailors and coastal provinces hold festivals in [Kitharu's] honour" (nothing strikes me as less likely) and "the Festival of the Eclipse is still held in [Dembria's] honour" (weird, since Dembria's blotting out the moon is what unleashed the undead upon the world) while "holidays and ceremonies are held in [Omara's] honour" (fair enough, farmers need holidays, but why would they honour a goddess who cannot guarantee anyone a good harvest?). The World of Juravia Sourcebook (2000) makes it clear that conventional polytheistic piety holds sway in Juravia. It's like the Apocalypse never happened. But I like the Kibbes' apocalyptic myth - or bits of it anyway (I'll discuss the unfortunate bits in the third and final blog in this series). It seems to me that there ought to be a fantasy setting properly based on it.

Maybe I'll end up designing it myself...

0 Comments

In a previous post, I analysed Forge Out Of Chaos' rules for Divine Magic, used by the worshipers of Grom and Berethenu. This led to details about Forge's odd mythology (these are the only active deities and both are imprisoned in the subterranean fiery hell of Mulkra) and Ron Edwards' observation that it is typical of 'fantasy heartbreakers' to belabour mythological backdrops but ignore the role of religion. To be fair, of all the heartbreakers that he reviews, Edwards concedes that "the best of the bunch is Forge: out of Chaos, probably (as I read it) because this material was taken the least seriously and written for fun imaginative-background rather than as a personal fantasy opus." Edwards sketches out a brief checklist of the way these games travesty religion while obsessing over mythological settings:

Let's see how Forge measures up to the first two; the third will have to wait until the next blog. The God-Wars The Forge rules open with a mythological treatise, explaining how the Supreme Being (named 'Enigwa') created the world and ordered it to be beautiful and harmonious. Enigwa then snoozes (having become Enigweary?) and his children, the gods, are left in possession of the paradise he has bequeathed them. The gods start off perfect too, but they become more differentiated as the ages pass, with some developing selfish or aggressive traits. The Supreme Being is disturbed by this discord and, I suppose, Enigwakes. He draws the gods together in fellowship to create Humanity and then commands the gods to be mankind's instructors and guardians, for Man shares the best and worst traits of the gods. Then Enigwa disappears, off to create new worlds (his Enigwork?), strangely blind to the trouble he has set in motion. The gods immediately fall out and a triumvirate forms: Necros the god of Death teams up with his brothers Grom the god of War and Galignen the god of Disease. Grom starts creating his own servitor races by mutating humans: the orc-like Higmoni, the Klingon-inspired Berserkers and the one-eyed gorilla Ghantu. After a polite pause to register their shock at this impiety, other gods follow suit: Dembria, goddess of Creation, creates the albino Dunnar; Katharu, god of nature, creates the lizardy Kithsara; Marda, goddess of Animals, creates the avian Merikii; Omara, goddess of harvests, creates the half-pint Sprites; even virtuous Berethenu, god of Justice, creates his loyal Dwarves. I'm not sure who creates the wheezing weasely Jher-em; Marda, I suppose. The Elves aren't attributed either, but Terestar the god of Time appeals to me as their creator. The gods go to war, tearing up the landscape. Marda is particularly wrathful, creating monsters and Dragons to defend her pristine wilderness. Necros figures out how to create the Undead to be his creatures. He tricks Dembria into creating the moon to blot out the sun, so that his undead army can dominate the lightless world. Then, when his sister Shalmar the goddess of Life pleads with him for peace, he murders her Enigwa returns to judge his creations and he isn't happy: his Humans have been mutated into other races, the landscape churned up and rearranged, Shalmar dead, the moon blocking out the sun: it's not pretty and the Supreme Being is Enigwrathful. He pronounces judgement on Necros, flinging the death-god into "the endless void." Grom gets dropped into the fiery depths of Mulkra for his crimes. Berethenu has the chance to repent but is too noble to accept forgiveness: he leaps into Mulkra to be imprisoned with Grom. Enigwa gathers together the remaining errant gods and takes them away with him, leaving the world of Juravia to recover from this divine ruckus. The various races are left to pick up the pieces in a god-free world. They reconstruct the principles of magic but, since these powers no longer come directly from gods, Pagan Magic is uncertain and has nasty side-effects. Down in Mulkra, Grom and Berethenu seize moments between burning in eternal agony to invest their worshipers - Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors - with Divine Magic. There are rumours that the gods occasionally sneak back to Juravia when Enigwa isn't Enigwatching and the monsters and undead horrors unleashed during the Great Wars are still out there, causing trouble. All this rationalises a fantasy world with monsters, races and magic, Dumb Names Guilty as charged, but it's not all bad. If Enigwa is a dumb name for the Supreme Being then chain me to the wall. It's got 'enigma' in it but the W has been flipped, see? The overall effect hints at something African, which is great. There are a lot of GFNs (Generic Fantasy Names), just syllables with -a or -ia or -ar added on the end. 'Necros' is lame, being filched from the Ancient Greek nekrós meaning 'corpse.' I'm sympathetic to the Tolkien Conceit, that fantasy names are just translations into familiar English of words that are really in other languages, so Peregrin Took was really "Razanur Tûk" in Westron. But if you're going to do that, be consistent. Shalamar should be named after the Greek for 'life' which is Zoe, Grom should be Polemos, Galignen should be Nosos and Marda should be Therion. Fine names all. Some of the names have a whiff of poetry to them. Galignen has connotations of 'malignant' which is clever. I like the -u names Berethenu and Kitharu, which suggest (to me) something Babylonian or perhaps Romanian or East Asian. Grom is a near-steal from Robert E Howard's Crom, the war-god Conan respects (I was going to say 'worships' but that's going a bit too far), and in turn adapted from Celtic myth. But it's all a mad jumble really and not in a good way. Over on Zenopus Archives, there's a 'Holmes Random Name Generator' that creates fantasy names extrapolated from the quirky imagination of Basic D&D author Eric Holmes. These names may be random but they're not GFNs: Chor Paldon, Zoque Kar, Losho the Blue, I could do this all day. Try it yourself: These names are random collections of syllables, but they're still evocative. Crucially, they're not European in flavour. They sound like they're from a slightly alien fantasy land: not Marda but Mardreb, not Dembria but Drebael. Thomas Wilburn slams Forge for (among other things) starting off with 10 pages of myth-making before we get a content page, never mind rules: "mythology belongs in a background section in the main text, not at the very front where the reader has to wade through it just to get to the game." But the trend for '90s RPGs to kick off with thematic fiction or campaign setting before introducing the rules was well-established long before Forge came along. No, I don't object to the positioning of mythology at the start of the book and it's well-written: in fact, it's the best-written part of the whole book. I just wish the Kibbe Brothers had knuckled their foreheads and come up with names that were genuinely evocative or thematically consistent . What cultural setting do these deities connote? Five minutes of Google-fu (or half an hour with a decent encyclopaedia) prompts suggestions like this: This harmonises the gods' names (I like that -u ending and -ara as the feminine suffix is more interesting than plain -a or prettified -ia) and Nergu re-names Necros along Babylonian lines. Just sticking an O- prefix in front of Grom works wonders (and connotes 'ogre'). Why would all the races use the same names? The creatures of Kitharu and Mardu get a synthesis of Babylonian and Yoruba names and the 'Grom-folk' (Higmoni, Berserkers, Ghantu) get Japanese-inspired adaptations. I think the Dunnar would have Celtic-style names (reverencing Dembara and Dobuna, Berethenu as Berethos and Grom as Crom) and let's go with Norse-style for the Dwarves (re-titling Berethenu as Borothor and Grom as Grotun) and Greek-style for the Elves (Berektor and Grotos). Names do amazing things: they imply a world. Un-fun Strictures No surprises here. Grom Warriors and Berethenu Knights both have to follow an honour code. For Grom-ites it's a simple barbaric code of never running away, fighting face-to-face and taking part in a demented yearly rally. Berethenudians have a chivalrous equivalent that gets more restrictive as they advance: eschewing armour and fighting fairly. From a roleplaying perspective, these strictures are intensely external to your character's identity. It's frustrating for Berethenu Knights that they cannot wear plate mail and have to give away a tithe. Not being able to attack from behind makes a few combat encounters slightly more awkward than they have to be. But you can 'tick the boxes' with these requirements and play your cleric just like all the other characters. What we don't learn is what foods are forbidden, what clothing must be worn, what sex acts are condemned, what daily rituals must be enacted. In other words, what is like to live in the service of this god?

The oddity is not that clerics suffer such strictures, it's that no one else does. There's a tendency for lay people to adopt the strictures associated with holy folk in order to make their own lives more holy. Over time, these strictures become the sort of codes of dress, diet and sexuality that make up a religious lifestyle. If Berethenu Knights tithe and behave chivalrously, then this sort of chivalrous, charitable code will spread to other people who don't have magic powers to lose. If Grom Warriors fight one-on-one and boast of their kills, then a culture of dueling and boasting will also become normative in society. One way of handlig this is through Benefits & Detriments (pp17-18), which currently involve trading of advantages (being tall or stocky or having a resistance to poison) against drawbacks (arachnophobia, deafness or being one-eyed). Religious strictures make good Detriments and violation can be punished by removing experience checks or imposing bad luck (-4 on next Saving Throw). It's interesting to reflect on what else Grom or Berethenu expect from followers. Are Berethenudians vegetarians or virgins? Or are they expected to marry and have families? Are Grom-ites forbidden to marry or acknowledge their children? In the real world, sexual abstinence is the distinctive feature of religious observance yet it gets no mention in RPGs like Forge. Distinctive dress codes and grooming are features of real world religions: Jewish peiyot (side-curls) and kippah (circular head coverings), beards in Islam, turbans in Sikhism, bindi (forehead dots) in Hinduism and Jainism. Often, these create a more abiding stereotype of a religion than anything the members actually believe or do. How does one recognise a Berethenu Knight? Do they wear sashes, turbans, shawls or phylacteries? Do Grom Warriors shave or wear hair down to their knees? Of course, to answer these questions, you need to have a cultural conception of the fantasy world these people inhabit. Is it Northern European, Middle Eastern, Asian or African in tone? In order to decide whether Berethenu Knights wear turbans or kilts, you need first to consider what sort of ethnicity they represent. Unsurprisingly, the Forge art represents 'Humans' as white Europeans (e.g. p12, p86, cloak, trousers, cean-shaven, mullet). That's disappointing (and not just because of the mullet) and it will take another blog to explain why.

This leads into the most important topic, which is how a fantasy world is shaped by its religions - a point widely ignored in games like Forge - and I'll get stuck into that in the next blog.

It's time to take a look at Forge's magic system. This is the only aspect of the game to attract universal praise. Ron Edwards identifies the magic system as "genuine innovation" and even Thomas Wilburn (who hates the game) admits that " the game has an excellent way of dealing with high-powered wizards." Forge splits magic into two broad types: Pagan Magic (aka Sorcery) and Divine Magic (clerical stuff). In fact, all the magic is ultimately divine in origin, being passed onto lesser races by the gods. The difference is that Divine Magic is still a direct gift of the remaining (albeit imprisoned) gods, while Pagan Magic covers mystical forces that mortals have learned to master without the gods' ongoing assistance. When you sink those 10 skill slots into the Magic skill, you must make a decision: Divine or Pagan? This is particularly important for dimwit Ghantus, who normally have to spend twice as many slots to acquire any skill at all. Since Divine Magic is granted directly by a god and doesn't reflect on the caster's own intelligence or education, Ghantus can learn Divine Magic for the standard 10 slots rather than a nearly-impossible 20. Let's take a look at Divine Magic this week. Knights of Berethenu and Warriors of Grom

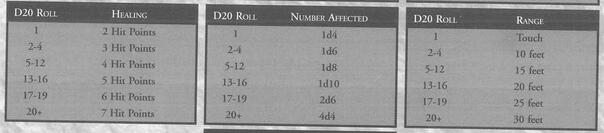

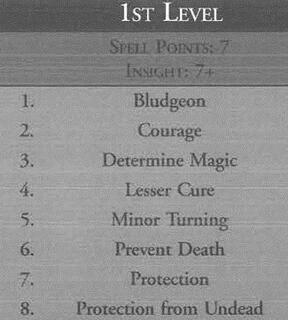

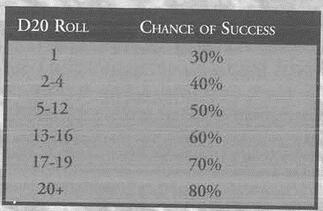

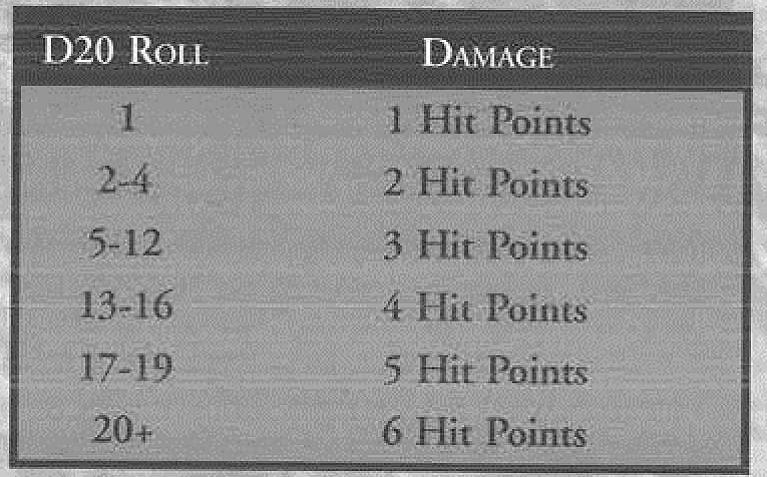

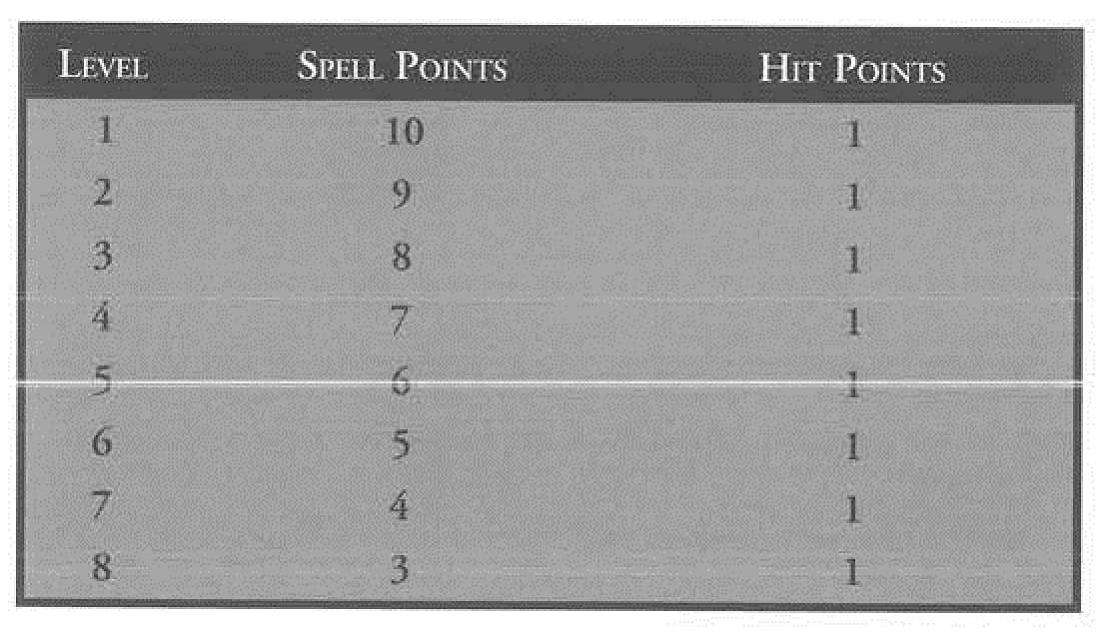

There are a few downsides to Divine Magic compared to Pagan Magic. You cannot spend extra skill slots to be better-than-normal at Divine Magic: Berethenu and Grom give you what they give you and that's that. No taking a chance with higher level spells: at 1st level Magic you get 1st level spells and that's all. You cannot "pump" the spells either, pushing your luck for better outcomes as Pagan Mages do. Finally, advancing in the Magic skill requires acts of servitude to the god (tithing for Berethenu, personal trophies for Grom) and, as usual, there's a clerical code which, if broken, strips you of your godly powers for ever more. Basic Mechanics You get a number of spell slots equal to your Intellect (let's say, 7) and you could fill them with different spells, giving a typical Divine Mage 7 starting spells. First level Divine spells cost 7 Spell Points (SPTS) to cast and a Mage typically has 20-25 SPTS (2d10, doubled), with Kithsara lizardfolk having a half dozen extra SPTS because they are, you know, very mystical. This means you will cast 3, maybe 4 spells before running out of magical juice. Rather than knowing a wide spread of spells, it might be better to start with a smaller selection, say 3, that you are really good at. This is where the 'schematics' come in. These are tables that determine the variable factors for each spell: its range and duration, how much damage it causes or heals, etc. Instead of learning a new spell, you can use up a spell slot to re-roll on the schematics for an old spell and take the better of the two results, or three results if you use up a third slot to re-roll yet again. Going up a level in the Magic skill earns you a bunch of new SPTS (around 15, typically) but also grants you a new set of spell slots. You will use some of these to acquire spiffy new high level spells, but you might use some of them to re-roll your old lower level spells, gaining a +2 bonus for each level higher you are than the spell you're trying to improve. This encourages Mages to develop a honed and curated set of spells, with optimal characteristics for range, duration, damage, etc. It also means that, as the blurb on the back of the book promises: "No two mages are ever alike!" The higher level spells cost more SPTS to cast (14 for 2nd level, 21 for 3rd level and so on) and also have minimum Insight requirements (8+ for 2nd level, 9+ for 3rd, and so on). If you think the 8th level spells look mighty fine, remember that they cost 56 SPTS (OK, you probably have 120 by that point, over 150 if you're Kithsara) and you need an Insight characteristic of 14 (ah... that's a problem). Berethenu Magic: a paladin by any other name The 1st level Berethenu spells give you a flavour of what this god offers. There's Determine Magic (a pointlessly verbose alternative to the D&D stalwart, Detect Magic), Courage (it's Remove Fear), a Lesser Cure (that will be Cure Light Wounds then) and Minor Turning which lets you turn lesser undead, like Skeletons and Zombies, just like a D&D cleric. Protection (which grants a good Armour Rating) and Protection from Undead (which outright repels undead attacks who fail a Saving Throw) have obvious roots in D&D.

Most of these spells have variable Range and Duration and it's not really worth re-rolling these. With its one minute melee rounds (why? why? more about this maddening idea in a future blog), Forge de-emphasises tactical movement, so range is rarely a crucial factor. Even a pretty rubbish 1st level spell will last 11 minutes, which is good enough for most combats.

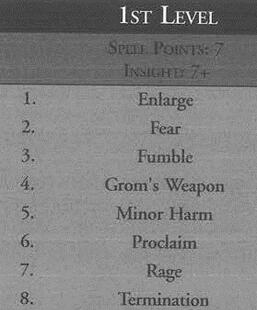

The higher level spells really just introduce more exciting versions of these effects. At 2nd level Armour grants someone a bunch of magical Armour Points (5 is disappointing, 30 would be amazing!) and that's a pretty significant power. More spectacular healing magic becomes available along with spells that boost Attack Values and Parrying, confer immunity to various horrible conditions and the 5th level Immobilize is our old friend Hold Monster with an even more prosaic name. At 8th level, Resurrection makes its appearance (for those Berethenu Knights with 14 Insight), but that requires the permanent sacrifice of a point of Stamina whether it works or not. This is a functional set of spells that definitely offer an edge in combat, a solution to undead pests and some healing that's faster and more potent than binding kits and Healing Root. It's very dungeon-orientated: everything is for combat or the aftermath of combat. There's nothing like Commune with Deity (understandable, perhaps, since the deity is burning in Mulkra), no spells beyond Determine Magic to answer questions, provide guidance or inveigle clues out of the Referee. Even though Berethenu is god of Justice, there are no spells to detect lies, punish wrongdoers or bind people to their promises. But that's fantasy heartbreakers for you. Their myopic focus on breaking down doors and killing monsters is a virtue if that's all you want to do. But it's a spell list crying out for a bit of elaboration. By the way, notice how, by making turning undead a spell that some Divine Mages will know but others won't, Forge preempts what D&D went and did with clerics? Berethenu Knights have a final power, to convert their Hit Points into extra SPTS. They gain 7 SPTS from doing this - enough to power a 1st level spell. At 1st level of Magic skill, this drains 12HP. Since a typical character has 15HP, you won't be doing this often. But by 5th level, once the cost has dropped to 8HP for 7SPTS, it might be tempting in order to pull off a crucial spell. Grom Magic: putting the laughter into slaughter

Grom's Weapon summons a magical weapon to hand; it's a good weapon too: +1 actual damage, cannot notch, cannot be dropped. This is one of the few spells worth re-rolling to get a good Duration.

Termination is an odd spell. It grants you a high score in the Final Blow skill that you use to decapitate an opponent reduced to 0HP or less, rather than letting them bleed out. Few people bother with this skill, since it's easy to coup-de-grace your enemies once the battle is over - or just leave them to die in agony. But every now and then you need it, such as when enemy Berethenu Knights are healing fallen comrades as fast as you can chop them down. If you learn this spell, you probably want to re-roll it so that it works reliably. Proclaim is that rare beast in this game: a cultural spell. Grom Warriors are supposed to gather yearly in a big rally and boast about their accomplishments. This spell lets you boast alone. Why would you bother with it? Well, for campaign reasons, like setting off on a journey far from home! A rare concession that there might be stuff going on outside the dungeon. High level spells keep the focus on mayhem: blinding people, poisoning them, shattering weapons, demolishing armour, gaining extra attacks, ogre strength, all good stuff. There are more spells that duplicate rarely-bothered-with skills like Gaze Evasion and useful skills like Melee Assassination. There are even some helpful spells, such as empowering and repairing your own armour. While Berethenu Knights are raising the dead, the 8th level spell Vengeance turns the Grom-ite into a berserk killing machine that attacks friend and foe alike. The focus on dungeon skirmishing is less out-of-place here. But since Grom is god of War, it's strange there are no spells for leading armies, staging ambushes, routing infantry or spreading plague. Moreover, there's a lack of sneaky spells. The focus is on the straightforward berserking champion, but surely Grom Warriors can be devious assassins as well. It would be nice to have spells for heroic leaps, surprise attacks, disguising yourself as the enemy and laying traps.

With Grom and Berethenu you get the clear impression of a designer wanting to make clerics 'cool' but impatient with all the 'religious stuff'. What you get are two species of a$$-kickers. In his article More Fantasy Heartbreakers (2003), Ron Edwards ponders why the authors of these indie games were all so indifferent to religion, concerned only with "what must a cleric avoid doing in order to get his healing spells back or when a character gets a minor bonus." D&D 5th edition, with its divine domains and clerical metaphysics, looks back at Forge as across a vast gulf. I'll give some thought to Forge's own take on fantasy mythology in another post. Yet there's no denying that Berethenu Knights and Grom Warriors (perhaps, especially Grom Warriors) are fun fellows down a dungeon and, so long as that's where we keep them, their essential incoherence doesn't emerge. If you want to use Forge for a more conventional Fantasy RPG campaign, something with politics and cultural differences and ethical issues to resolve, then can these two clerical killing machines be made relevant? "A good question," as Maz Kanata says, "for another time.".

Last week I posted up a festive one-shot scenario on the Blog. It was my first attempt at a 30-minute dungeon and it was a dismal failure because it took me an hour and a half! But it was a cute tale of a dysfunctional peasant family being assaulted by malevolent winter spirits and the PCs being on hand to save them - a sort of reverse-dungeon where the PCs are defending a site and the monsters are the raiders. I took a bit of time to convert the scenario to Forge Out Of Chaos as part of my project to support this forgotten '90s heartbreaker. The finished scenario is on the Scenarios page. It encouraged me to correct a few mistakes. The scenario features principle NPCs Vadim and Vasilisa who are ordinary peasants but have special ancestors. My first draft was a bit confused about whether heroic Dadushka and witchy Babushka were the parents or grandparents. The final edit clarifies: they were grandparents to the three children and therefore parents to the married couple. This also clarifies a theme that was in my mind when composing the scenario but didn't get the sort of emphasis it needed. Vadim and Vasilisa have both turned their backs on the careers of their adventuresome parents: Vadim is no warrior fighting demons and Vasilisa is no witch safeguarding the home. They are the lesser children of greater parents; they live in a security their parents earned but which they themselves do not appreciate. Vadim doesn't even realise the awl and poker combine to make his father's magical spear Snowmaiden while Vasilisa uses her mother's wand as a distaff for spinning.

The other theme that I muddled on the first draft was the role of Morozko the beggar. I intended him to be an otherworldly figure, with his lunatic-savant babblings and his magical bag of gifts. The tattered robe of red and ermine hints at his true identity: Father Christmas.

The edit enabled me to clarify Morozko's role. Vasilisa turned him away when he came begging and this sin against the ancient code of hospitality is what triggers the family's harrowing. Morozko hides in the lumber shed, plotting revenge, but is discovered by little Nikita, who brings him food and drink. Morozko offers her a gift in return and takes her to the Kurgen - the old Howe where the winter spirits are imprisoned - and opens it. Nikita takes the snowglobe as her gift, but by doing so she unleashes Krampus and the Winterfiends. This might seem a pretty equivocal 'gift': isn't Morozko punishing the child who helped him to spite the mother who rejected him? In a way, yes, but faerie wisdom runs deeper than that. Morozko's gift to Nikita is to return her parents to her: not the unimpressive trapper and his superstitious wife, but the heroic role models that Vadim and Vasilisa can be, if they rise to the challenge of the Krampus. The snowglobe is an apt metaphor here, because Morozko is shaking the little cottage and its occupants, disturbing their peace and security, to bring out a greater beauty when the tumult settles. Of course, for this theme to come across clearly, the PCs' arrival should not be accidental. They meet Vasilisa while heading down a forest trail as night draws on, but how did they get to be there? Perhaps, earlier that day, at a fork in the road, they met an old man in blue and white who directs them down the left hand trail. This figure is Morozko, of course, and he has misdirected them - but only in order for them to pass by the stile where Vasilisa waits for heroes to come to her aid. The revised version includes some advice for the Referee in roleplaying Morozko. He won't be attacked by monsters if there are any other targets. He can navigate the blizzard and part the Holly Hedge to rescue prisoners. He understands everything going on. But he appears to be a gibbering fool. He functions as a 'Referee's Friend' since his crackpot utterances can direct PCs towards vital goals (reading the spellbook, assembling the spear, matching the wand and ring, returning the snowglobe). Ultimately, he could be used as a deus ex machina to bring about a successful resolution, but that requires some inspired roleplaying to get Vasilisa to repent her hard-heartedness and the two adults to demonstrate their heroism to the sceptical winter god. How does it work with FORGE? Forge has some advantages over straightforward D&D in a scenario like this. Most classic fantasy RPGs are games of attrition: your health, spells and weapons get used up and, once they're exhausted, you've failed. Old school D&D suffers from the fact that the PCs have so very little to lose. This can make it hard to tell one of those 'night from hell' storylines where waves of attackers come at the PCs, whittling them down. Most 1st level D&D characters struggle to survive the first whittle! Forge offers characters armour to take the brunt of damage (at least, at first) and Spell Points (SPTS) to use and re-use spells. Then, after an encounter, Field Repair can be used to restore armour and Binding can restore Hit Points, so long as the repair kits hold out. This gives the PCs a bit more longevity in this sort of scenario, meaning the Referee can torment them more enthusiastically. This helps support a group of introductory Forge characters through a night with several bruising combat encounters. Converting the scenario means working with Forge's distinctive mechanics. There are materials in the cottage and the byre that can be used as armour repair kits and binding kits; there are extra healing roots among Vasilisa's stock. Mages can sleep to regain SPTS but, since they need to sleep for at least 2 hours, they will be lucky to get undisturbed rest. However, the spell book upstairs can recharge SPTS if it is opened to the right place. Krampus himself is a ghastly threat. He's modeled on the build for a troll (two claws for 1d8+5 each!) with the added bonus of 1d6 regeneration every round. That's too tough for starting characters, even with a fully-activated Snowmaiden canceling the regeneration. But if you end up fighting Krampus, you've probably failed the scenario. The players need to talk to the NPCs, learn about Vadim and Vasilisa's parents, figure out what Nikita stole from the howe and return it, hopefully with the aid of the Wand and Ring or the Spear to get through the Holly Hedge, but Morozko could be roped in to open the way if the Referee is feeling kind.

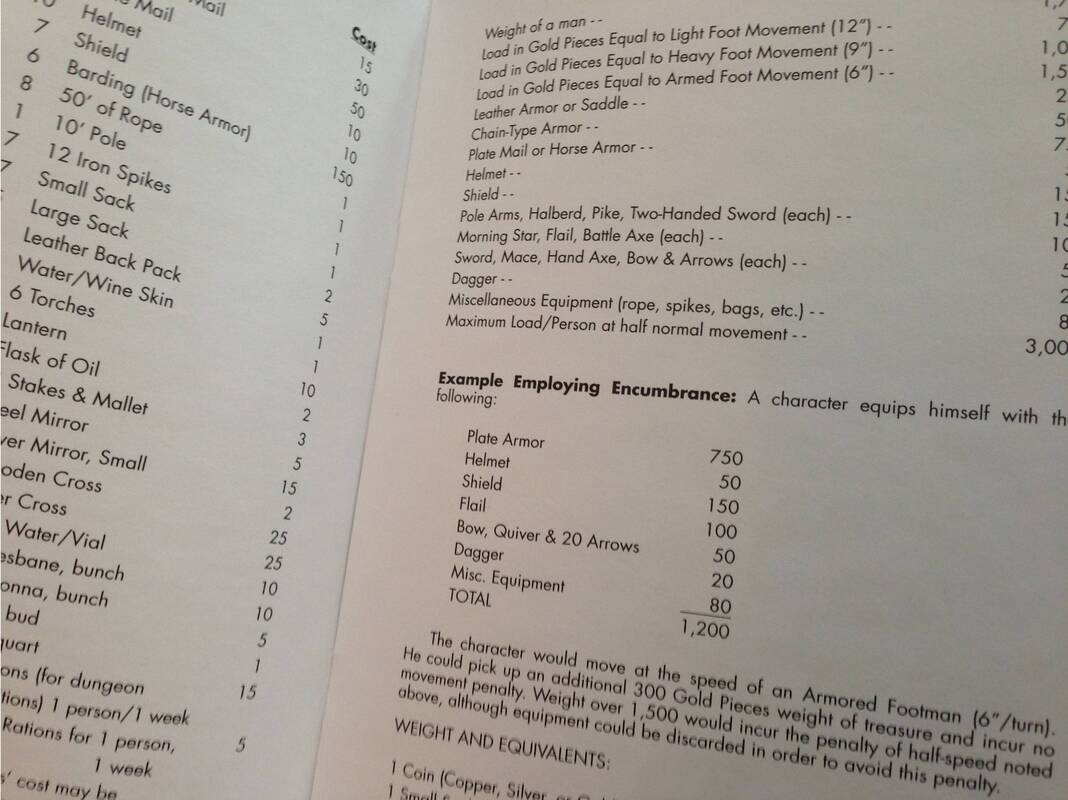

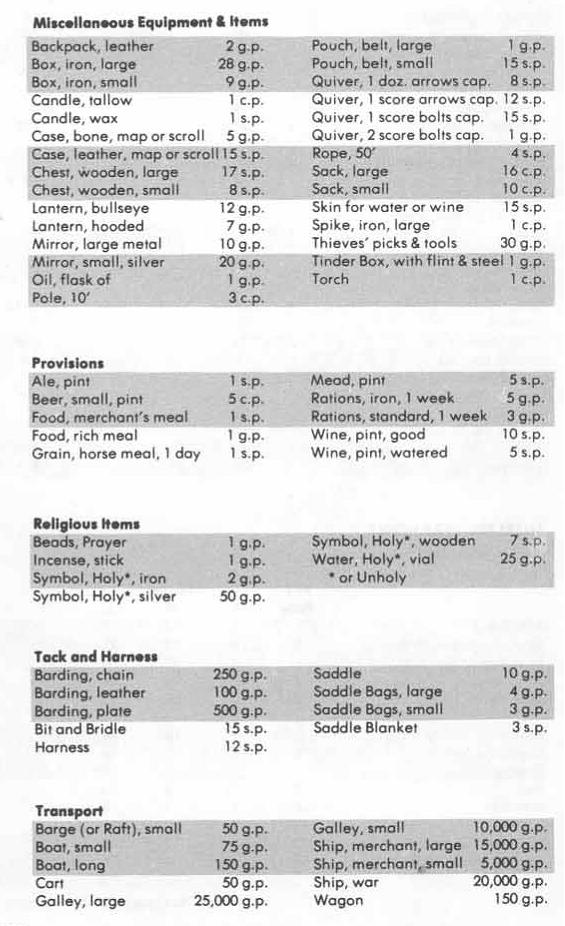

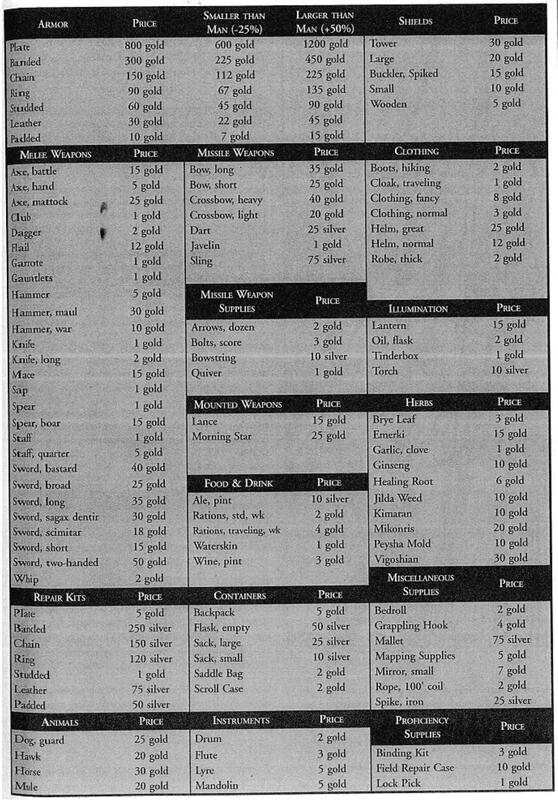

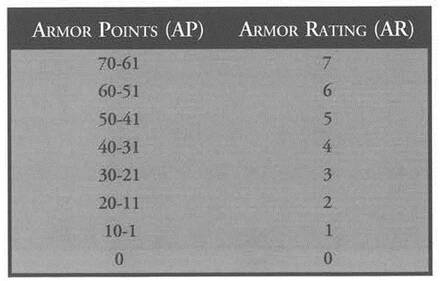

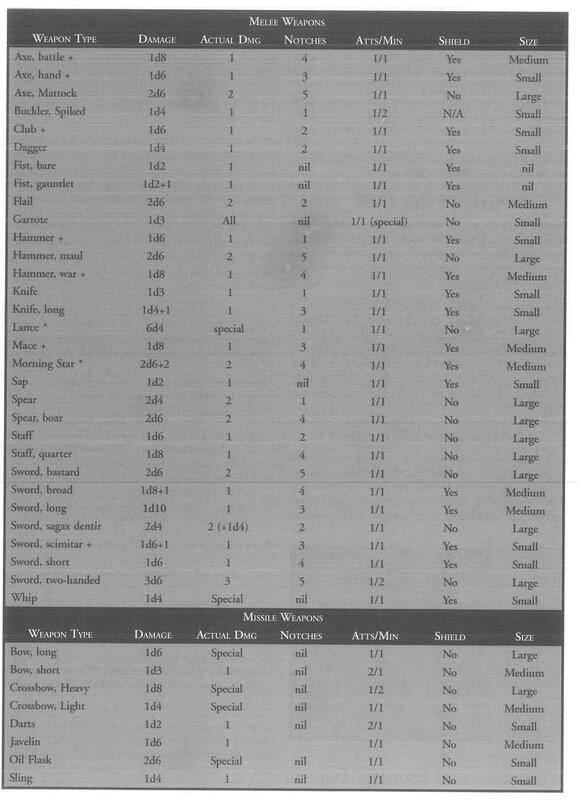

Equipment lists were features of RPGs right from the outset. In D&D, they stayed fairly standard, offering distinctive dungeoncrawling tools like 10' poles, mirrors, torches, tinder boxes and garlic buds. Forge follows the conventions of D&D slavishly: the equipment list is a clone of that presented in D&D, streamlined somewhat with the non-dungeoneering stuff left out: no barges or galleys, no different types of horses, no barding or saddles (despite the presence of Mounted Melee skills and rules), no tapestries, no songbirds. The only list that gets expanded is musical instruments (an oddity) and varied prices for different sizes of armour (a rare oversight in AD&D). The armour follows the canonical D&D progression from padded to leather and studded leather, ring mail to chain mail and ultimately plate armour. Ron Edwards (2002) finds some comedy in the reverential repetition of the D&D tropes in games like this: "we older role-players memorized the weapons-list in the 1978 Player's Handbook through sheer concentration and fascination, such that its cadences took on a near-catechistic drone." But really, if it ain't broke, why fix it? The 'Miscellaneous Supplies' section of Forge's equipment list reads like a template for an adventure in itself: bedroll, grappling hook mallet, mapping supplies, mirror (small), rope (100' coil), spike (iron). There are promising first novels and movie screenplays that could be reduced to a list like this and if it doesn't get you through a dungeon then it's hard to imagine what else will. Forge even adopts D&D's immemorial mechanic for determining your PC's starting funds: rolls 3d6 and multiply by 10 to get your gold piece allowance. Fantasy Economics Some differences and distinctions emerge at this point: the prices. In general, things cost twice as much as in D&D and, down at the cheap end, the price hike is even bigger. For a D&D fighter with 100gp, you could buy ring mail (30gp) and a broadsword (10gp), maybe a shield (10gp) and short bow (15gp) with a quiver full of arrows (1gp plus 12sp) and you've still got over 30gp left to invest in backpacks (2gp) and those miscellaneous supplies. Good luck getting mileage like that in Forge. The ring mail alone is 90gp, the sword 25gp, the bow 25gp, the backpack 5gp: only the shield holds its old value at 10gp. Starting Forge characters are going to have to scale back their expectations. With those weapons, leather armour (30gp) just about breaks the bank; sir might prefer economical padded armour (10gp) if he wishes to avail himself of the miscellaneous supplies (all in for 25gp). For AD&D characters, padded armour is a badge of shame, the sort of thing you wear when there are rust monsters about. In Forge, it's the new normal. And did I forget to mention spell components? Minor Damage spell components cost 35-60gp, depending on the school of magic. And those are the cheap ones! Maybe re-think that broadsword... I don't mind the new economics. The last blog pondered what is supposed to motivate adventurers to seek treasure in a game where gold doesn't equate to experience. Here's a partial answer. Players will have to make several dungeon delves before they are rich enough to equip themselves in line with their aspirations. The diamond an Elementalist needs for Minor Protection Spells costs 280gp; a suit of plate armour costs 800gp, 1200gp if you're a Ghantu. That should keep you busy. It's interesting to try to map this economy onto the real world. Back in the '80s, Paul Vernon wrote an excellent series of articles for White Dwarf called Designing a Quasi-Medieval Society for D&D. Vernon constructs D&D economies around the 'Ale Standard' and calculates that, since a small beer costs 5 copper pieces in AD&D and 50p in the real world (HA-HAH! yes, this was 1982), we can conclude that a copper piece is 10p, a gold piece is £20 and work up from there. Vernon points out how pricey lanterns are at £240 but reminds us that fantasy economies are inflationary: gold is cheap because dungeon-robbing adventurers keep flooding the market with it. In AD&D, a pint of ale costs a silver piece, 10 coppers, so £1 - I'm not sure why Gary Gygax decided to make ale twice as expensive as beer (historically it was, if anything, the other way round) but ale turns up on the Forge price list too: a pint of ale costs 10 silver. I can't find anywhere in the Forge rulebook where it breaks down the currency, but judging from other prices it seems there are 100 silver to a gold piece. Let's say a pint of ale these days costs £5 (it's cheaper in Wetherspoons, I know, I know). If 10 silver equates to a fiver, then a Forge silver piece is 50p and a Forge gold piece is £50. Rolling 3d6 x10 for your gold, this means Forge adventurers go into their careers with a start-up fund of £5000, on average! Let's try some conversions. £40k for a suit of plate armour? That's like buying a good car, which seems about right. £1250 for a broad sword seems a fair price. £100 for a dozen arrows will make you more careful with them in future. £5 for a bowstring will give you twice the reason to curse when it snaps. £100 for hiking boots is pretty reasonable and £150 for fancy clothes makes me think Forge's tailors need to get unionised. £750 for a lantern is steep. Paying £1750 for that Manticore Spike to cast Beast Magic Damage Spells - and that's the cheapest of the spell components - makes you wonder if kids from poor backgrounds ever become Mages. You can calculate some other costs from this. A night's accommodation would cost 1gp, 2gp for somewhere fancy, 3gp for somewhere luxurious. You could eat in a cheap tavern for 10sp, or pay 1gp in a classy restaurant. The price list suggests a pint of wine costs £150, which suggests wine is a luxury in Juravia! Bind those wounds One distinctive feature of Forge is the availability of binding kits (3gp, £150) usable by anyone with the Binding Basic Skill. These can be used to heal 3hp lost to ordinary wounds. There's also Healing Root (6gp, a stonking £300), which heals 1d4 HP lost to any sort of damage. This makes Forge adventurers much less dependent on clerics in the party for in-dungeon healing. If you've got the money to load up on this sort of first aid, you can patch yourself up after most fights. And speaking of patching up... Repair that armour Another distinctive feature of Forge is the system for repairing armour using the Field Repair Basic Skill. A PC with that skill must own a Field Repair Case (10gp, £500) and use repair kits specific to each type of armour to do the work: a padded armour repair kit costs 50sp (£25), a chain mail kit costs 150sp (£75) and a plate mail kit costs 5gp (£250, wow!). There are no shield repair kits - the rules on p22 imply ring mail repair kits work for shields. The repairs are automatically successful: the kit gets used up and the repairs take 2 minutes per AP restored (p37). This means sewing up 10AP damage to a leather jerkin takes 20 minutes; riveting 40AP damage to a plate breastplate takes over an hour and a half. This is an invitation to Wandering Monsters, but if the tinkerer is repairing everyone's armour, the work could take several hours. Time for those Mages to get some sleep and restore some SPTS (5 per two hours of sleep, maximum 20 per day). This lends a delightful rhythm to a Forge dungeoncrawl: fight monsters, rest up and fix armour, fend of Wandering Monsters, then press on. It seems wrong, however, that all of the damage to armour can be repaired as long as the repair kits last out. Can you really restore leather armour reduced to 1AP tatters and shreds to its 20AP pristine glory, just by spending 40 minutes on it? Is two hours of labour enough to rebuild an entire suit of plate mail? It's tempting to house rule this. Field Repair can restore armour to the bracket above its current status, but no higher. This means that, if you have a suit of chain mail (5AR, 50AP) and it takes 27 damage (now 2AR, 23AP), you could repair it up to 40AP (4AR) but no higher. The remaining work has to be done in a proper workshop by someone with the Armourer Skill. This introduces inevitable deterioration into armour, no matter how many repair kits you bring along. This is an important consideration because, in the absence of any rules for encumbrance, wealthy PCs could theoretically load up with hundreds of repair kits. What, no encumbrance? There's no encumbrance. Quite early on, D&D wedded itself to a persnickety system of tracking encumbrance down to the smallest gold coin: chain mail is 300gp encumbrance, a broad sword is 75. A PC can carry 500gp without penalty and higher Strength extends this threshold. Everyone hated the constant book-keeping and delighted in magic armour (50% encumbrance) and bags of holding to bung the loot in and forget about it. Forge just never mentions encumbrance at all. The Speed characteristic on p5 makes no reference to how weighed down you are: with SPD 3 you can run 180 yards/minute (a stately 6mph), in or out of armour; with SPD 5 you're covering 340 yards (12mph, fast for a jog but slow for a sprint). Look, I get it. Encumbrance is boring. Just wear the best armour you can afford or are allowed (if you're a Mage) and shove all the treasure you find into sacks and leave the bean counting to the nerds. And yet, it's not good enough really. Once they have a bit of money behind them, players will want to load up on armour repair kits and binding kits. Why carry two when you can carry twenty? More than twenty? How many more? Is there even a limit? Without going down the road of weighing up every single item, we can propose a quick house rule. PCs can carry big items (armour, shields, weapons, quivers, 100' coils of rope, lanterns, rations, some spell components) with metal armour counting as two big items; there are also small items (repair kits, binding kits, most spell components, daggers, iron spikes, torches, water skins). You can carry a number of big items equal to your Stamina and a number of small items equal to your Strength. Sacks and backpacks become big items when full (Referee's judgement when that happens). Too many big items and your Speed drops by one for each excess; too many small items and you count as carrying an extra big item. If you want to go further with this, you can put small items equal to your Strength into a sack or backpack to make them all count as a big item. It's not perfect, but it imposes a sort of limit on PCs. A PC with Strength 8.5 and Stamina 7.5 could carry 6 big things (metal armour, shield, sword, quiver, bow, that makes 6) and 8 small things. If she puts 8 repair kits into a backpack, that counts as a 7th big thing. That leaves 8 slots for other little things, like half a dozen torches, a tinder box and a binding kit. Useful Herbs The final addition that Forge makes to the classic D&D accessories is the avalability of magical herbs. This sort of thing was already a big feature of ICE's Middle Earth Roleplay (MERP) and it's tempting to extend the list here with homegrown additions. But the starting set covers most occasions. I've already mentioned Healing Root, which is worth stocking up on for the 1d4HP healing it offers. Jilda Weed has a gooey sap that stops a character on zero or negative HP 'bleeding out' - very useful, as my players discovered recently when they didn't have any! Kimaran Root increases your strength by +.5d10 (anything between +0.5 and +5.0, on average +3.2) for 1d4 hours, but with a 75% chance of removing -0.1 from your Stamina permanently. Vigoshian Root similarly adds 10d6 SPTS (average 35) for an hour, with a 50% chance of reducing Insight by -0.1d3. Both of these boosts are great (especially, perhaps, the Vigoshian Root) but players will be loathe to use them too often with those costs. Peysha Mold glows in the dark for 12 hours: not as bright as torches but (if you care about that sort of thing) much less encumbering. Ginseng offers a +4 bonus to Saving Throws vs Disease for 5-30 minutes. Emerki offers a similar bonus against Mind attacks for 1-6 hours and Mikonris against Poison for 10-60 minutes.. Other plants are more situational. Garlic counteracts the Intellect-draining effects of the Duvadin (an invsible parasite) and Brye Leaf counteracts the poison of a Mevoshk (12' long snakes with a paralysing venom).

The philosopher Epicurus claimed that "skilful pilots gain their reputation in storms and tempests." This is a pretty good template for RPG experience systems: you endure terrible things and you get better at the things you used to succeed. Some ancient history D&D originally bunched a whole load of applied skills together as a 'character class' and, when people found these templates too narrow and prescriptive, offered variant classes and sub-classes with different proficiencies. You're a thief who likes killing people: welcome, assassin! A cleric who likes nature spirits: greetings, druid! Non-weapon proficiencies (NWP) started appearing in 1985, with the Unearthed Arcana expansion that made a lot of Dragon Magazine material canonical. NWP became a major feature of AD&D's 2nd edition in 1989. However, NWP always sat awkwardly with AD&D's class system. They're really different approaches to doing the same thing and they get in each other's way. Meanwhile, D&D's glamorous cousin Runequest (1978) went a different way. Runequest abandoned character classes (well, almost: Shamans and Rune Lords inserted themselves) and defined PCs entirely by their skills. The system, which acquired a life of its own as Basic Roleplaying (1980) and undergirds Call of Cthulhu (1981), shames D&D with its simplicity. All skills (from swinging a sword or parrying a blow to tracking trolls or leaping chasms) are values on a 0-100 scale and you test them by rolling d%, looking to roll equal to or under your skill. Succeed and you get an 'experience check' against that skill. At the end of the session or adventure, roll d% for each checked skill and if you roll higher then the skill increases. The point about rolling higher is important. Starting PCs have low skills and fail most of their rolls but if they succeed then they are very likely to improve: if your Sneak skill is 10% you will fail 9 times out of 10, but if you succeed you check the skill and you only need to roll higher than 10 on d% for it to increase. Conversely, experienced characters succeed often but find it hard to improve: with Sneak 90% you rarely fail to be stealthy but you need to roll 91-00 to increase the skill any further. Almost all later RPGs took a position somewhere between these poles. Rolemaster (1980) offered classes AND skills, with the skills multiplying with every expansion. Later games often offered character classes as mere templates, enabling players to invest in a coherent and thematic set of 'class skills' and perhaps penalising out-of-class skill choices by making them more expensive to acquire or improve or else privileging in-class skills by having them advance faster. This maintained the convenient 'meta' of character classes ("I'm a fighter" and "I'm a rogue") to speed up character creation and simplify adventures while allowing players to customise their PCs. In many '90s RPGs, character classes were replaced by factional allegiances that worked in the same way. For example, Vampire: the Masquerade (1991) offered signature powers for different Clans then allowed the players to put together any permutation of skills and abilities. How Forge does it: Basic Skills Ron Edwards (2002) points out that 'fantasy heartbreakers' like Forge invariably claim to be "innovative" when in fact they are just reinstating alternative systems from the beginnings of the roleplaying hobby. There's nothing new under the sun, and Forge really just reinstates Runequest/Basic Roleplaying. However, even when rules aren't original, they can still be elegant. Forge takes familiar materials but puts them together well. Forge PCs have a number of skill slots equal to the sum of their Intellect+Insight - 15 on average. Basic Skills can be bought which confer unvarying advantages, as opposed to Percentage Skills which confer a chance of success with the possibility of failure. Basic Skills are more like abilities than skills. If you know Binding you can use binding kits to treat wounds; if you know Horsemanship you can attack at a penalty while mounted. The Exceptional Characteristic Basic Skills let you add +1.0 to a characteristic; Exceptional Intellect and Exceptional Insight cost 2 slots because they might cause you to recalculate the number of skill slots you are entitled to. There are some oddities here. History is a Basic Skill which means the Referee will give you any information you need about the history of an area, no roll needed. Similarly Hunting gives you a flat 50% chance of foraging food for the next 2-5 days in exchange for 6 hours of hunting and reducing travelling rates by a quarter. Most games would make these Percentage Skills, with the possibility of failure but also the option to improve them. These Skills reflect Forge's assumptions. It's a game of going down dungeons and killing things, not making long wilderness journeys or researching historical mysteries. Activities outside of the dungeoncrawling paradigm are marginalised, expressed as "yeah you did it" abilities that move the plot along. Why should a failed History roll mean you never hear about the dungeon? Why should a failed Hunting roll mean you struggle to locate the dungeon? Ron Edwards finds this truncated perspective laughable, pointing out that, for heartbreaker RPGs, dungeon adventuring is "not only the model, but the only model for these games' design - to the extent of defining the very act of role-playing." But the thing is, I don't mind about that. If I'm going to play a dungeoncrawl game, I want a dungeoncrawl system. Forge's laser-like focus on creating characters for dungeoneering is only a flaw if you believe this RPG ought to have loftier ambitions. But why should it? Movin' on up: Percentage Skills With Percentage Skills, we're on familiar territory. The skill's score is your chance of using it successfully on d% and, once used successful and checked, you try to roll above the skill to improve it with experience. Forge has a few contributions of its own. In Basic Roleplaying and similar systems, everyone gets access to every skill, many of which start with lowly scores (e.g. Stealth 10%, Disguise 01%) to which skill points are added. In Forge, if you don't select a Percentage Skill then you simply cannot do it at all and the ones you select have a starting value set by the sum of two characteristics (e.g. Blind Fighting is Dexterity+Awareness), which is a modest figure (average 15%). This makes for simplicity at the risk of absurdity. What, I didn't select Climbing so I can't even try to climb the castle wall? Without Hiding I cannot even try to hide myself from that patrol - I have to just stand there, out in the open? In the context of '90s and early C21st RPGs, this is maddening stuff. In the context of Old School Revival RPGs, it's less of a problem. OSR emphasises Referee judgement over rules and skills. Let the Climbers roll their skill (baseline Dexterityx2%) and give everyone else a lesser chance (baseline Dexterity%) as you see fit. Forge also lacks a system for scaling skill success against difficulty level: what about smooth walls and observant guards? The Referee is invited to raise or lower skill chances based on the situation. For OSR Referees, this is plain sailing. In Basic Roleplaying you check a skill for improvement the first time you succeed at it, but in Forge you check it every time you succeed at it. You could end up with a LOT of checks , especially in a skill like Leadership that a PC might use at the start of every combat encounter or Open Locks that might be used dozens of times. This partly gets round one perennial problem in percentage skill systems: the Lockpickers' Queue. This is a phenomenon where, faced with a locked door or chest, the party members with the worst lockpicking skills try to open it first, with the expert lockpickers stepping in only when everyone else fails. Why? Because the poor lockpickers might succeed by fluke and, if they do, they get to check their skill and are very likely to improve it; the experts are almost guaranteed to succeed and don't need the skill check so badly: they're likely to fail to improve. It's a clunky insertion of meta-knowledge into roleplaying behaviour. In Forge, you can check a skill multiple times, so the expert has an interest in using his skill successfully because, with enough checks, he should manage to raise it a little. Some of the Percentage Skills raise problems. Tactics is a skill you may use every round in combat to boost your DV2 against flank attacks. Since there's no penalty for using it, PCs will use it every round. Does that entitle you to dozens, maybe hundreds of checks? Not quite. You only get a check when the skill is used significantly, when there's "something to gain from it" (p20). The rulebook doesn't clarify but presumably to gain a check in Tactics you have to boost your DV2 on a turn when you suffer an attack against your DV2. I'm not sure whether it should be an attack that misses as well. Either way, you're rolling this every round but only checking it when you get attacked - grr-r, book-keeping... Better, I think, to treat Tactics like Leadership: it's a roll you make at the start of combat, if it succeeds it gets a check and the benefit lasts for the entirety of the encounter. Missile Evasion lets you add your Awareness bonus (if you have one) to your DV2. This is another fiddly skill and, in any event, the rule that missiles attack DV2 ought to be scrapped. What should Missile Evasion do instead? The rule as-written means that, when you get shot at, you can try to hike your DV by a couple of points. One option is to make it function just like Giant-Fighting: possession of the Skill adds +1 to your DV against these attacks and a successful roll adds +5! Another option is to make Missile Evasion a Leveled Skill that benefits your DV1 against missile attacks you can see coming. Then there's Jeweler: why is this even a Percentage Skill at all? If History is a Basic Skill ('You're a historian: you know the history') then why is Jeweler something you have to make a skill test to do, instead of just automatically identifying gems ('It's a big diamond, probably worth 500gp')? The answer is another of Ron Edwards' "unquestioned assumptions": you find jewels in dungeons but you don't find historical curiosities. If we take this skill at face value it means that when PCs find jewels and fail to evaluate them, they're just 'Jewel #1' and 'Jewel #2' and have to be randomly assigned at the end of the adventure. Players get their jewels evaluated when they sell them: 'Cool, Jewel #1's worth 500gp!' or ''Drat! Jewel #2's worth 5gp!' There's a merry lottery to this, but rational players will sell the jewels en masse and split the gold they got for them, which raises the question of why it's worth evaluating jewels in the dungeon at all! It would make sense if Jeweler was a skill at cutting and polishing gems to increase the value of jewellery (say, by 20%). Or if jewels lost 10% of their value when converted to cash unless a PC Jeweler had previously evaluated them. Otherwise, this Skill needs to be reassigned to the Basic Skills to be worth investing in. A similar case could be made for reassigning Plant ID and Track ID to Basic Skills. If someone's got the skill, they should be able to tell peysha mold from jilda weed. The idea of having the skill but rolling badly and failing to recognise a herb that's on every PC's shopping list is absurd. One step at a time: Leveled Skills Leveled Skills are the smartest feature of Forge's three-legged stool and, if the game needs further development, then all the skills should probably be revised as Leveled Skills. It's just the best system the game offers. It's characteristic of fantasy heartbreakers that they don't try to present a unified mechanism, retaining instead D&D's 'diff'rent rules for diff'rent rolls' approach, but Forge comes closer than most to the d20 system D&D evolved into in 2000, just 2 years after Forge was published. Leveled Skills start at 1st level and go up, potentially to 12th level, possibly higher. They are mostly combat skills like Melee Weapon and Missile Weapon, Melee Assassination and Missile Assassination, Backstabbing and Brawling, but they also include Magic. The level translates directly into your Attack Value (AV) and the level of spells a Mage can cast. Leveled Skills also have a percentage score that usually starts at a characteristic multiplied by 4 or a pair of characteristics doubled (so averaging 30%). This gets checked in the same way as Percentage Skills but increases in the opposite way: you have to roll under the score on d%, so it starts difficult but gets easier and easier as the score rises. When it hits 100% you go up a level and the score drops to its base level again, minus 4%. Eventually it drops to 0% and at that point you cannot increase it any further. This means an average character who starts with a skill at 30% will get to 8th level in the skill then be unable to advance any further. The Elvish racial benefit of adding +25% to the Magic Skill doesn't just mean the character advances faster (Joe Average Elf starts at 55%) but has a higher level limit (14th!) before the base score drops to 0% or less. If the game were to be revised,it would be a good idea to gives each race a +25% bonus to a particular Leveled Skill, giving them a head start and extending their potential in the future. You can probably tell, the Leveled Skills mechanic intrigues me. I like the way your starting score also contains the limits of your ultimate advancement; I like how you start improving slowly then speed up, but when you go up a level you drop to a lower starting point and have to struggle longer before advancing. But what about the loot? In D&D, treasure is really important. Loot equates to experience points, so the thrill of finding a sack of gold or a string of pearls is the excitement of knowing this brings you closer to your next level-up. In skill-based RPGs like Forge, this connection is broken. You increase skills by using them, not acquiring money. But why, then, are adventurers venturing into dangerous dungeons if it's not for hidden treasure? Surely there are safer and more certain ways of increasing your skills - like military service, for example. What's their motivation? One point needs making and that is that the de-emphasising of treasure can be a good thing. In converting a D&D adventure to Forge, I halve the treasure, maybe cut it even more. No need for chests filled with thousands of coins. Money still has a use in Forge. Mages have to buy spell components and most of these are priced beyond the reach of starting characters. You go down into dungeons to get the money to access your full spell list. Armour and weapons are more expensive than in D&D and, unlike in D&D, they break and have to be replaced. Purchasing extra binding kits and armour repair kits makes for extra resilience down in the dungeon. Equipment and shopping in Forge are considered in another post. Nonetheless, adventurers quickly have more money than they know what to do with and they gain no benefit from it in terms of their powers and abilities. It's tempting to house rule tuition costs before a PC can level up a skill (say, 100gp times the square of the new skill level, so getting from 1st to 2nd level costs 400gp, from 2nd to 3rd costs 900gp, and so on).