|

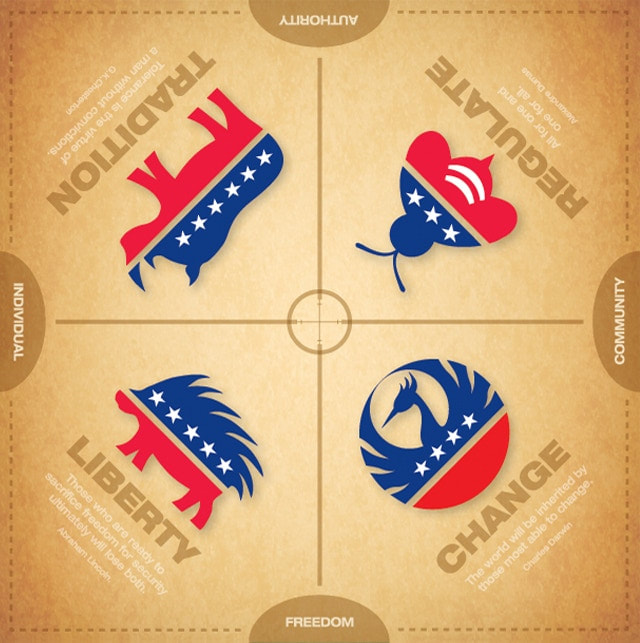

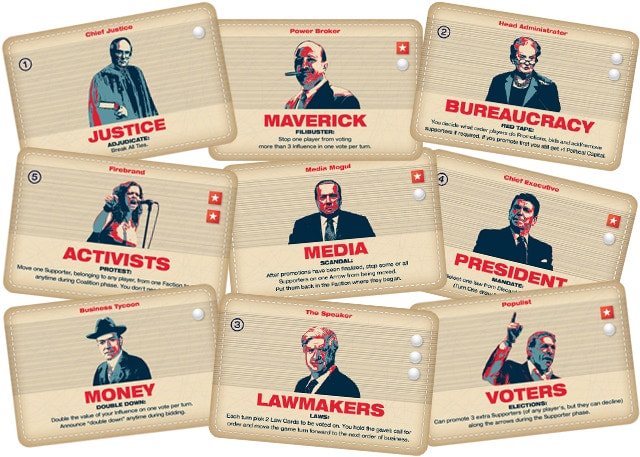

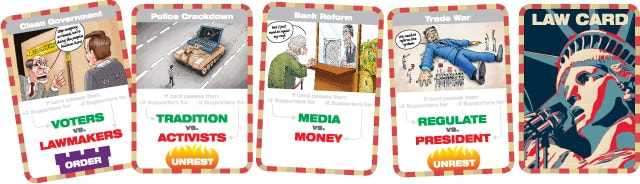

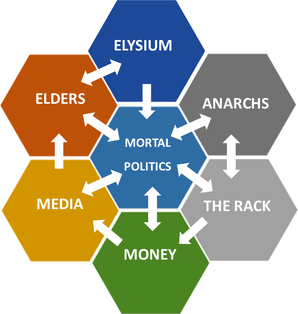

At the start of September this year, an old friend died, suddenly and tragically. Not the least of David's many talents, accomplishments and (dare I say it) obsessions was a prodigious collection of board games and roleplaying games. One of these games made its way to me, still in its shrink-wrap from its 2012 Kickstarter campaign. In honour of Dave and deferring to his excellent judgement of games, we unwrapped it and started to play. David Turner 1981-2022 The game is DEMOCRACY: MAJORITY RULES, designed by Mark Rein-Hagen and published by Make Believe Games (BGG link). It's a blend of area control and negotiation, themed around American politics. It caught our imagination, but it also inspired me to use it in a RPG context - this post is part game review and part RPG brainstorming. But first the review. Democracy: Majority Rules - a game of politics & negotiationDemocracy: Majority Rules (D:MR) is one of those Kickstarter disaster stories. It arrived from the creative mind of Mark Rein-Hagen, a man with a sage-like reputation as the designer of Ars Magica and later Vampire: the Masquerade and the World of Darkness that grew out of that game. Rein-Hagen's name is enough to draw a crowd to anything he endorses, never mind creates. D:MR was Rein-Hagen's first project after a career break from gaming and offered something very high-minded: an experience that would combine roleplaying as the wheelers and dealers in the American political machine with game mechanics for passing laws and forming coalitions and expansions that would adapt this premise into other contexts, like the Arab Spring, the French Revolution or the end of the Roman Republic. Moreover, the game seemed to offer a penetrating insight into the nature of politics itself. Who wouldn't love a game like that? If you have tears, shed them now. The project foundered. Rein-Hagen suffered ill health but also managed to alienate backers and his production team, the game got lost in warehouses for two years then finally made it out to gaming tables long after goodwill and excitement had expired, minus a few of the promised stretch goal extras. There's a lot of harsh language for this game on the message boards, but that just reflects sky-high expectations. The game itself, now that it can be seen for what it is, is a lean but gripping experience that never outstays its welcome on the table. No, it's not the 'Great American Board Game'; it's not an innovative new roleplaying game; it's not a penetrating insight into the nature of politics itself. But it's good. How You Play It Pick your political position: Tradition, Change, Regulation, Liberty or Centrism. These will make a difference to who gets punished and who benefits when Laws are passed later. The modular board represents seven factions vying for power: Justice, Bureaucracy, Money, Media, Voters, Activists and Lawmakers. Players allocate their supporters (cubes) to these factions and the person with the most supporters on a faction acquires its power card. The first clever touch is that, for each faction, players can form coalitions to deny the power card to the person with the simple majority; if a coalition does this, it must agree on which member to award the power to. Coalitions are fluid: you might be in coalition with a rival on Bureaucracy but opposing them on Activists and this might change from turn to turn. Next you get to promote your supporters, which means putting cubes on the arrows that will shuttle them over to adjacent factions. Of course, this upsets the delicate coalitions. You can only assign one cube to each arrow, but the person controlling Voters can break this rule. Once it's all done, the person controlling Media can break a scandal, sending some cubes back to their original faction. There's some pretty intense manoeuvring at this stage. Some of the factions are especially desirable as they let you place more supporter cubes (e.g. Activists, Voters, Media) and some give you extra influence tokens you will spend later (especially Lawmakers and Bureaucracy). Others have neat powers. In addition to the powers you get from controlling factions, there is the President and the Maverick. The President is awarded by the player with the most supporters spread across Voters and Media - but they cannot award the Presidency to themselves. The Maverick goes to the player who is coming last in terms of points and powers. All of this is to set up the main stage of the game. The Lawmaker chooses two Law cards and the President chooses a third card from the Law card discard pile. Then everyone votes on whether to pass these laws or strike them down. The Law cards are quite witty. Each defines a faction (e.g. Voters) or a specific player (e.g. Tradition or whoever is the President) which benefits if the Law is passed and one who is penalised. Lots of bargaining and horse trading ensues, then each side bids their influence tokens to get the Law passed or see it discarded. Some powers apply here, such as Money who can double the value of the influence they invest or Maverick who can freeze out one opponent with underhand or unexpected tricks. The rules suggest players get into role here and make little speeches before each vote. In fact, optional rules suggest following all sorts of procedures using faux parliamentary language. The game comes with a wooden gavel that one player uses to end one phase and move things along to the next. The Law cards matter because, if you are the beneficiary of a Law that gets passed, you add two supporter cubes to the board, but if you are penalised, you remove two cubes; the person who invested the most influence tokens gets to keep the card. If the Law is struck down, the card gets discarded and no one is affected. Regardless of the Law passing or being struck down, everyone on the 'winning' side of the vote claims a victory point. Once all this is over with, you move on to organising your coalitions, reassigning the Power cards to their new owners, then gathering a new load of influence tokens and adding a new set of cubes to the board, based on the Factions you're in charge of. If you didn't use your Faction's Power in the last turn, you can claim an extra victory point for that too. Rinse and repeat. You play through 5 turns of this then check to see who has won. Add up your victory points and claim extra ones for having the most cubes on the board or in particular factions. Except, wait. There's a clever catch. Several Law cards are keyed as UPRISING or ORDER. If there are more UPRISING cards than ORDER cards in players' possession at the end, then mobs take to the streets: no one's accumulated victory points count and everything is decided by cubes on the board. In other words, an amazing leveller for the players who lost their votes or used up their powers during the game. How Good Is It? Once you get to grips with its quirks, you can zip through D:MR in an hour; if it lasts longer, it's because you're enjoying the wheeling and the dealing. And so you should! There are lots of reversals of fortune, volte faces, promises made but not fulfilled, cruel betrayals and even a bit of steadfast loyalty. You can play as a two-faced bastard or a pillar of decency or a bit of both: it's up to you. Despite all the shenanigans, the victory engine is quite simple. You will probably win if you have the most cubes on the board. Declining to use your powers to rack up extra victory points is an uncertain endeavour, because, if your rivals pass a bunch of UNREST Laws in the final turn, everything you saved up is now worthless. All the more reason to persuade the other people with lots of victory points (i.e. your main rivals) to vote those crazy Laws down! Another reason for not neglecting the board amidst all the voting and the speeches is that it has a distinctive structure. You can't place a supporter cube directly into Lawmakers, but you can promote a cube there from anywhere else. Justice and Activists are both 'dead ends' and once you promote supporters out of Bureaucracy and into Money, it's hard to make them return (well, I mean, would you give up money for a clerical job?). Activists can become Lawmakers but it doesn't work the other way round. All of which means you can end up with your cubes 'trapped' in Factions you don't care much about, unable to get them over to the ones you do. Unless, of course, you can persuade Activists to use their special Power on your behalf. It's a shame this game imploded the way it did. It's not the Messiah, but it is a delightfully naughty boy. It makes some sweetly parodic points about politics and finds a way to balance Euro-style cube placement with across-the-table arguing and pleading. If you want to throw in an element of roleplay, you can, but it's not essential. Reading what was planned for D:MR makes me even more sorrowful. An 'Uprising' Expansion was going to focus on military coups, tribal loyalties and street protests. Further expansions were set to vary the Factions, Powers and Laws to simulate political crises of the past, like the 1964 Civil Rights movement or the 1989 Prague uprising - or the trial of Socrates in 399 BC. But it was not to be, alas alas .... So I was thinking about RPGs ...A lot of backers hoped (and Rein-Hagen perhaps intended) that D:MR would be a game-changing elevation of roleplaying and board games into a new ludic form. Well, it didn't turn out to be that. But the game still has applications for roleplaying. Hear me out! One of the pleasing aspects of RPGs is the supervenient political intrigue that shapes ground-level encounters and events that PCs experience. Usually, the GM concocts this shadowy narrative - or perhaps rolls on tables to generate the twists and turns of political convulsions. Or maybe you prefer to roleplay this meta-plot. Players set aside their normal PCs and the GM assigns them the roles of warlords, spymasters, diplomats and chancellors at some sort of Big Fantasy Committee Meeting or Embassy Grand Ball. Everyone roleplays an agenda, makes deals, concocts schemes, grants permission for for the commission of unspecified outrages ... and the GM makes notes of all that's said and then puts it into action over the next few months of the campaign. That's fine - in fact, with the right players, theatrical props and GM preparation, it's better than fine, it's superb. But it doesn't suit everyone and it can backfire - or simply fail to deliver the sort of information the GM is looking for to plan the campaign ahead. So, how about using Democracy: Majority Rules to replace this? Democracy: Vampires Rule Imagine you're running a game like Vampire: the Masquerade where the PCs are street level vamps but the great events of the city are shaped by the power struggles of the centuries-old vampires known as the Primogen. Here's what you do. Set up a game of Democracy but use factions like these: Instead of political positions like Liberty or Tradition, choose a Vampire Clan (four from Ventrue, Toreador, Tremere, etc. plus one like Gangrel or Malkavian to be the Centrists). The cubes represent your agents, spies, ghouls and minions. The GM will have to create a deck of Event Cards to replace the Law Cards. These are themed around possible plot developments in the campaign to come, with a Clan/Faction that stands to benefit and one that will be punished. Instead of Uprising v Order, you have Jyhad v Masquerade, with too many Jyhad cards in play meaning the Undead have been exposed.

Or maybe 'Recruit Sabbat Allies' gets struck down. In this case the Sabbat aren't going to turn up during the campaign - although the PCs might be sent to make such overtures by their Gangrel or Tremere masters, only to find themselves opposed by the Brujah and Toreadors ... because those are the Clans who successfully voted these event down. It's pretty easy to come up with a couple of dozen event cards like this: Release Plague Rats Into The Sewers (Nosferatu vs The Rack), Assassinate the Mayor (Money vs Mortal Politics), Sire A Celebrity (Elysium vs Media), Breach Masquerade (Media vs Elders), Blood Hunt (Elders vs Anarchs) and Secret Diablerie (Anarchs vs Elysium) all spring to mind as well as Clan-specific plot threads like Build A Blood Golem (Tremere vs Elders), Vampire Ball (Toreador vs Elysium), Methuselah Awakens (Ventrue vs Anarchs) and Lupine Attack (Gangrel vs Brujah). If you keep a record of who voted for what and how the different Factions changed hands during the game, you've got the main intrigues of your Vampire: the Masquerade chronicle all mapped out, right there. It works for other RPGs too, but especially the political-faction ones like Ars Magica or Band of Blades. It would be fun to build a Call of Cthulhu campaign this way, playing D:MR with Great Old Ones instead of political positions (Nyarlathotep as the Centrist, of course) and Factions replacing Activists with Cultists, Bureaucracy with the Great Race of Yith and Lawmaking with the Miskatonic University. It would work for a D&D campaign, replacing the political positions with the cardinal Alignments (and their fantasy religion representatives) and the Factions with the Thieves Guild instead of Media, Mage College instead of Voters, Mercenary Leagues instead of Activists, Dwarvish mines instead of Money, City Watch instead of Bureacracy and Elven Rangers instead of Justice, perhaps with the King's Council, the Lich Lord or the Drow Conspiracy replacing Lawmakers. Play the game, then play the RPG campaign it generated. How cool is that?

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed