|

I was reflecting the other day about what a valuable resource 'dungeons' are and how odd it is that, in most campaigns, they don't seem to be owned by anybody. Which is peculiar, really, because dungeons are a powerful economic resource. Not only are they full of treasure, but magic items too. The skin and fur of magical beasts make great adornments for the upper classes and are usually ingredients sought after by mages. Even the arms and armour of humanoid denizens, the vellum and lore of lost grimoires and the access to seams of rare metals have financial value. Why would a local lord allow a dungeon on or near his estate to lie ignored until a bunch of no-account yeoman adventurers finally loot it? Because dungeons are dangerous, is one answer. You can order your knights and serfs to go to war because most combatants in a medieval war don't expect to die in it: the knights can expect to be ransomed and, assuming that disease and arrow-fire doesn't claim them, the peasant levy can hope to leave the battlefield with only bruises and scars. There are fatalities in war, of course, but the majority of combatants survive even on the losing side. Dungeons, on the other hand, are properly dangerous: orcs don't take prisoners, you can be eaten by ghouls, you can be killed by traps, you can be turned to stone! But that doesn't make dungeons valueless. If suicidally brave adventurers are going to descend into a dungeon, the local ruler will want them to be his adventurers, paying him a fee, taking a cut from their loot and certainly first choice of the best magic items, plus samples of rare commodities (lycanthrope fur, demon feathers, powdered gargoyle horn). What is a Dungeon: ruins, wizard sanctums or lairs? Dungeons are an odd concept. The idea that the fantasy landscape is strewn with these large multi-leveled subterranean labyrinths requires some explanation. Many RPG campaigns have abandoned the concept altogether in favour of more naturalistic assaults on fortresses, temples, woodland hideouts and caverns. But the dungeon exerts a grip on my OSR imagination and seems pretty central to the type of adventuring proposed in Forge Out of Chaos, so I'm going to think deeper about what dungeons are supposed to be. In Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the landscape of Cydoril is littered with Ayleid Ruins, easily distinguished by their bright marble surface works and full of slap-footed undead zombies and treasures such as the valuable welkynd stones. Weirdly, the PC adventurer seems to be the only person in Cydoril who realises you can get rich from plundering these places. Original D&D spawned this conceit, perhaps inspired by the Moria scenes in The Lord of the Rings; it's hard to trace antecedents in fantastic fiction for adventures happening in these dynamic labyrinths: elements of Lovecraft, Howard and Lieber? Ursula Leguin's The Tombs of Atuan (1972)? The Zenopus Dungeon, the ur-dungeon created by Eric Holmes for the 1977 'Blue Book' Basic D&D set, is located "on the ruins of a much older city of doubtful history and Zenopus was said to excavate in his cellars in search of ancient treasures." The idea of dungeons as the residue of a more advanced parent or pre-human civilisation has some resonance in history. In the Dark Ages, Anglo-Saxon tribes invaded Britain and discovered the cities of the Romans with their puzzling arches, heated bathhouses and vast plazas. Archaeology shows us that the Anglo-Saxons didn't inhabit these ruins but set up their villages alongside them, doubtless plundering them for stone and treasures while telling stories of the mysterious builders whom they believes to be 'ettins' or giants. One anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet describes such a city like this:

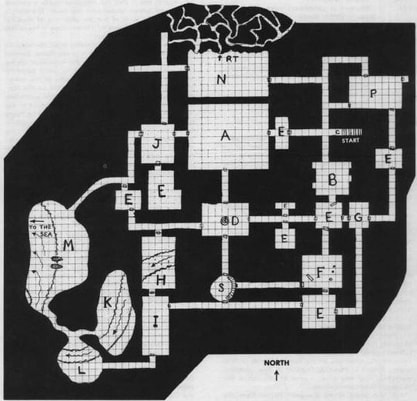

Another rationale for dungeons is that they are the architectural side-effect of stuff powerful wizards get up to. Wizards seem to need to delve underground: perhaps their magics only work at full effect far away from the sky, the sun and stars, from common people - or perhaps they like to be closer to rare minerals in the deeps of the earth or the resting places or summoning portals for eldritch beings. Again, Eric Holmes got here first, with Zenopus the Magician making "extensive cellars and tunnels underneath the tower" which is the proximate cause of the Zenopus Dungeon in Holmes' Basic Rules. The Zenopus Dungeon has been updated and expanded for 5e D&D Gary Gygax took the conception of dungeons in a different direction. For Gygax, dungeons were just lairs, either cave complexes monsters had moved into like squatters (such as the Caves of Chaos in Module B1: The Keep on the Borderlands) or else fortifications built by the monsters themselves to be their home and evil playground (such as the Against the Giants series). Modules B1 (Keep on the Borderland) and G1 (Steading of the Hill Giant Chief) both illustrate the Gygaxian approach to dungeon politics: the player characters are agents of the state and venture beyond its borders to impose sanctions on monsters in their lairs. It could be called a Rumsfeldian model... In Holmes' world, the authorities of Portdown "had a catapult rolled through the streets of the town and the tower was battered to rubble" after which the local dungeon was shunned out of superstitious dread. This fits with Holmes' psychoanalytic interest, with the dungeon representing the repressed id and the adventurers engaged in an exploration of the realm of the imagination that ordinary folks deny - a fine metaphor for roleplaying in general. Gygax's conception is more prosaic, but more alert to the political implications of dungeons. In his scenarios, the authorities send the players into the dungeons, with promises of reward or threats of what accompanies failure: the PCs are agents of the state, bringing law to the strongholds of chaos. As Ron Edwards gleefully points out: "In Forge: Out of Chaos, the very notion of doing anything that isn't treasure-seeking in a dungeon is completely foreign." Yet at least Forge has a clear rationale for dungeons to exist: they are from the God-War or the time before it: the shrines, prisons, mansions or workshops of the gods themselves or their semi-divine servitors. Places like that littering the landscape definitely have to factor in local politics. Are Dungeons like Royal Forests? In the Middle Ages, a 'Forest' meant an area of wilderness set aside for the king or regional lord; originally for hunting but later the emphasis shifted to timber for shipbuilding and war. 'Forests' were usually wooded, but the territory often included marshland, upland heaths, rocky massifs, it was all 'the Forest'. Forests and Dungeons have much in common. Forests are home to dangerous creatures (boar, bears, wolves but also outlaws) and other prestige animals (deer) that count as treasure. There are resources to be harvested: timber of course, but also coal and charcoal and related glassworks, salt mining, honey pasturage, fishing and herbs. But unlike typical dungeons, medieval rulers didn't allow just anybody to wander into a Forest and take advantage of the opportunities there. In 1100, Henry I created the Forest Laws of England, forbidding common people from entering Forests with weapons, cutting down trees, hunting or pasturing animals. Each Forest was overseen by a Keeper, appointed by the King and sometimes (as in Sherwood Forest) the Keeper-ship was hereditary. The Keeper would then hire Foresters (known as Verderers) to police the Forest and arrest trespassers or lawbreakers. These laws and the Foresters who enforced them weren't popular. Lots of rural communities depended on the surrounding woods and heaths for their food and raw materials, but were now forbidden from entering or making use of them. Laws were broken and Courts-of-the-Forest (Swainmoots or Woodmoots) set up to hand out punishments. Courts of Inquisition would be convened if a serious infraction was discovered - such as the carcass of a deer killed by poachers - and as often as not strangers in the community would be singled out for blame. Blinding and castration were the 12th century punishments for poaching the Forest deer. Peasants would have to be pretty hungry to risk this. As time went on, the Forests became a greater source of income for the Crown, so fines replaced mutilations (6 pennies for felling a green oak) and more licences were issued. Keepers, Companies and Dungeon Charters In a quasi-feudal setting envisaged in 'classic' D&D campaigns and in Forge, dungeons form part of the 'Forest' claimed by kings or powerful nobles. A court official (let's call him, without irony, the Master of Dungeons) would appoint Dungeon Keepers to manage the known sites. The Keeper would be a wealthy local landowner: a Squire or Baron, perhaps. The Keeper would in turn appoint serjeants-donjons, dungeon-constables or (my favourite) dinglemen to police the sites. More about them shortly. Of course, the Keeper doesn't want to go dungeon-delving himself: he has a big and profitable estate to run. And yet, the dungeon must turn a profit somehow... Enter companies of adventurers. The Keeper appoints a Company to represent him, granting them his livery and their own heraldic badge. The Chartered Company delves into the dungeon and, on returning, presents the Keeper (and his feudal overlord) with a choice cut of the treasures, including the best magic items. Sharp-witted GMs will realise that this is a very effective way of preventing the creep of wealth and magic items in a campaign. Players get to rake in the money for purposes of XP and use potent magic items while down in the dungeon itself, but on emerging they have to surrender half the cash and the best artifacts to their boss. Unchartered adventurers are poachers. If they evade the dinglemen and get in and out of the dungeon, they had better not convene in the Green Dragon Inn to split their loot, because word will surely get out. The Keeper, whose estate they have trespassed on, will confiscate ALL the loot and add a week in the stocks or a judicious flogging to send out the right message: robbing the dungeon is robbing its lord. The Chartered Adventuring Company will be strongly motivated to assist in the pursuit and add summary justice of their own: they didn't go to the trouble of acquiring their Charter and surrender their most exciting magic items to have a bunch of black market tyros poach from the dungeon right under their noses and run away with the best treasure. In a quasi-feudal setting, the Keeper grants his Charter to an Adventuring Company who reputation redounds to his glory, although valuable gifts would be offered by way of introduction to attract the Keeper's consideration. Eventually, successful Adventuring Companies go national in scale, holding Charters with lots of different Keepers and subcontracting the dungeon-delving out to less experienced groups who have to pay a fee to go adventuring under their badge and livery (and still offering most of the treasure up to the local Keeper). In other words, an Adventurers Guild comes about. Feudal lords delight in their Chartered Companies and their exploits. They expect them to do more than raid dungeons. They have to recount their exploits at banquets, demonstrate their weapon skills at tournaments, accompany their lord on hunts. It's not unlike winning a beauty pageant or a reality TV show: you're in demand. It's tiring being a court favourite and finding the time to get back down the dungeom again can be hard. In an imperial setting, relationships are a bit less personal. A regional governor will assess dungeon sites in his jurisdiction and sell permits to delve into them; the Empire will claim a percentage of the haul and first choice on the magic items. The appointment of a new Governor means the reassigning of permits and some intense negotiations between existing Adventuring Companies . Chartered Companions for and against Player Characters A simple way to start a campaign is for the PCs to be members of a Chartered Company in service to a lord or in receipt of a permit from a regional governor. Perhaps one of them has well-connected family or is related to a celebrated adventurer and can trade on the family name; perhaps someone inherited a fortune and sunk it into getting the Charter. This positions PCs for a dual life, where dungeon-delving sessions are balanced with intrigue storylines at court, where they must re-tell their tales, show off their skills, curry favour with superiors and lovers, make enemies and get sent on all sorts of non-dungeoneering enterprise by their lord or his courtiers: anything from hunting down lost livestock to escorting young maidens around the countryside. In this sort of campaign, rival unchartered adventurers are a scourge and the NPCs that dungeon encounter tables identify as 'Bandits' are probably these people. Enjoy seethng with resentment when your hempen homespun rivals clean out lucrative dungeon levels while you're kissing babies at the village fete; watch them level up faster than you and accrue more powerful magical treasures; delight in revenging yourself when the opportunity presents itself. Alternatively, the PCs are the unchartered adveturers: you are sneaking into the dungeon under cover of darkness, evading the dingleman and his henchmen, meeting at a secret trysting place to divide the loot, coming up with far-fetched tales to explain your wounds and scorched clothing. Most of all, you are running scared of the Chartered Company: those smug, lazy playboy-adventurers who get all the glory and who dog your footsteps, trying to expose you at any turn. The stocks or the scaffold await you if you're caught - unless of course you get wealthy enough to earn your own Charter. Meet the Dingleman The Dungeon Keeper doesn't want riff-raff poking around in his dungeons. Peasants in search of shelter or loot will probably get themselves killed or else provoke the subterranean monsters (pretty much the plot of Beowulf, where an escaped slave steals from a dragon's hoard and the indignant reptile visits destruction upon the tribe of the Geats). But it's not just that. It's even worse if those enterprising peasants succeed, and emerge from the dungeon as hardened veterans, with magical equipment, spell books and a heightened sense of themselves. Such 'heroes' aren't going to be content back behind the plough. More likely, they're the ringleaders of the next Peasant's Revolt. Even if they don't revolt, peasant-adventurers promote something just as bad: social mobility. The ruling classes in a hereditary aristocracy don't want to be mixing with ploughboys and dairymaids who made their fortune plundering dungeons. This means dungeons must be policed and the dingleman or Dungeon Constable is the policeman. Probably, this person is the landowner nearest to the dungeon entrance, drawing an extra stipend from his lord for these duties. It might be a hereditary position or it might be offered to a retired war hero or adventurer, complete with a gift of land and a nearby cottage or tower from which to keep an eye on things. Obviously, the dingleman chases trespassers away from the dungeon entrance - or, in the case of large armed companies, takes a careful note of their identities. He's probably a capable warrior or magician and has some henchmen (perhaps his sons) and some big dogs to back him up. More than this, the dingleman's patrol probably includes the upper dungeon level too, or at least the corridors and rooms around the entrance. The dingleman knows about the traps and some of the monsters and might have some tricks (high pitched whistles, unpleasant-smelling incense) to chase away wandering monsters like slimes, rats, gelatinous cubes and mindless undead.

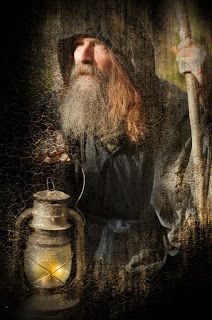

If the post is hereditary, some of these monsters knew the dingleman's grandfather and their working relationship can be quite sophisticated. Perhaps the Goblins tip off the dingleman when they're planning to raid the surface, so he can warn nearby farmers to lock their doors or spend a few nights safe in the town inn while their barn is being ransacked. Perhaps the dingleman tips off the monsters when the Chartered Adventurers hove into view: they can retreat to a lower level or hide away their children and womenfolk. That's what makes dungeon poachers so destructive: by descending unannounced on a dungeon and, by slaughtering the unsuspecting monsters, they damage the delicate trust-networks that have grown up around the site. I like to imagine Dungeon Hunts are popular with the more eccentric nobility: some young lordling and his entourage descend into the dungeon, clatter around harmessly for a few hours and do battle with something they can manage and emerge as monster-killers. The dingleman curates this experience, much like foresters set up a hunt by locating a likely quarry. The local monsters have to be forewarned and clear out ("You don't want to go messing with the young prince, he's well connected!") and in return point out to the dingleman the location of a suitable quarry ("Human, on the third level is predatory wyrm that devours our scouts: it would make a fine trophy for your prince!"). Of course, sometimes the dingleman really is working for the monsters, especially if there's a mesmerising Harpy on the second level that's turned his mind. What ought to be a safely-curated day of underground hunting can go badly wrong. This is the sort of occasion that sends in the player characters (even if they're unchartered) on a rescue mission. Dinglemen for and against Player Characters A friendly dingleman is the best source of likely-to-be-true rumours that a Chartered Company of Adventurers can have. He might be on hand to help with hauling large treasures out of the dungeon and willing to escort the party to a jumping-off point within the complex and offer directions from there ("These steps go to the third level; there's a room of glowing pillars, they say, and beyond that a witch's lair: she turns folks to stone!"). Naturally, in return the dingleman expects a share in the party treasure and perhaps the choice of a magic item. This, and also respect and fair language. If the party behave high-handedly, well, the dingleman can be much less helpful: rumours will be of the less accurate sort, directions vague, assistance grudging. If relations really break down, monsters will have uncanny foreknowledge of the party's approach. Unchartered adventurers usually avoid the dingleman at all costs. In a feudal system, the dingleman's loyalty to his lord (and fear of the punishments for dereliction of duty) makes it hard to bribe him or talk him round. He might show up to rescue PCs from a tight spot, only to escort them to a gaol. In other settings, the dingleman might be more of a jobsworth, amenable to a bribe or even taking a liking to young adventurers. Any assistance he offers will have to be secret though: remember the Chartered Adventurers and their sense of grievance? Best to turn a blind eye and leave it at that. I'm charmed by the idea of dinglemen: I'll make a point of incorporating on into my next dungeon. Here are some final thoughts about how a dingleman might function in a well-known dungeon: the Zenopus Dungeon by Eric Holmes. The Zenopus Dingleman You can read the original Zenopus Dungeon here, or look at my version for Forge Out Of Chaos or buy Zach Howard's 5th Edition adaptation for $1.99. I analyse the dungeon in an earlier blog.

Brubo patrols the area around the dungeon entrance to chase away trespassers but won't offer violence. He's too honourable to bribe. He will direct Chartered Adventurers to the stairwell and cackle about the endless corridors, the perilous graveyard, the sunken city of pre-human origin: he's great for setting the tone and functions as a Threshold Guardian (in Joseph Campbell's neo-Jungian terminology). Inside the dungeon, Brubo can be encountered as a Wandering Monster. He can help the party out against undead and carries a string of sausages to distract Giant Rats: in terms of Campbell's monomyth, he's a Helper and Mentor. Of course, he has been charmed by the Magician in Room F: he will direct or chase adventurers away from that area and fight to protect his master. On the other hand, he's a keen enemy of the Pirates in Room M and will assist even trespassing unchartered adventurers against them. If Brubo apprehends trespassers, they face a night in the stocks and confiscation of all treasure. If they keep returning to the dungeon, they will earn Brubo's grudging respect and he will increasingly turn a blind eye to their movements, especially if they deal with the Pirates. Post Script: I've added Brubo to my adaptation of the Zenopus Dungeon for Forge over on the Scenarios page.

6 Comments

Martin

4/2/2020 08:56:38 am

Really enjoyed this.

Reply

Jacob72

5/2/2020 08:48:09 pm

Fantastic post full of great ideas. I hope that you plan to build on them and develop the theme further. I prefer this type of dungeon - essentially recognising that you are playing a game where the objective is to explore and find treasure to build up reputation (experience points) over story-based games.

Reply

John Behnken

25/6/2020 05:57:38 pm

Fantastic article! I am completely and utterly charmed by the idea. I plan to incorporate it in to the current campaign. My players made a first run at Zenopus and reported back to the town council (who will, in short order, assign a Dingleman to the tower. Woohoo!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

30 Minute Dungeons

Essays on Forge

FORGE Reviews

OSR REVIEWS

White Box

THROUGH THE Hedgerow

Fen Orc

I'm a teacher and a writer and I love board games and RPGs. I got into D&D back in the '70s with Eric Holmes' 'Blue Book' set and I've started writing my own OSR-inspired games - as well as fantasy and supernatural fiction.. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed